by Dr Clare Craig FRCPath

How many people with ‘flu-like’ illnesses are being mislabelled as Covid?

Cases of Covid appear to have surged recently. Hospital admissions for Covid are now also starting to rise. To question how much of this rise is genuinely the result of Covid is to challenge the prevailing narrative, but as a scientist it is essential to ask hard questions. It is critical that we understand when someone is ill, but it is not Covid. We have limited resources for ‘Track and Trace’ and it is important that they are used wisely, especially when real outbreaks occur.

Scientists are grappling with what the rate of false positive results are with the current Covid test. The risk of a false positive result comes not only from aspects of the testing process itself but may vary from one population to another. It may even vary over time.

Every country has systems of external quality control for their laboratories. A summary has been published of attempts by these bodies to establish the risk of false positive Covid testing from other coronaviruses (one of the causes of the common cold). They tested against two strains of non-Covid coronaviruses. These showed between 0.58% and 0.96% were false positive with Covid testing. With large numbers of tests each day, this level of false positive cross reactivity could easily mean that screening testing across the UK, and indeed the world, has a high risk of misdiagnoses.

Co-infections are a genuine possibility with respiratory infections and are commonly seen with, say, influenza. A co-infection is where a patient is simultaneously infected with multiple viruses which may or may not include Covid. However, with low levels of Covid, when false positive test results are a real risk, then the possibility of a misdiagnosis of Covid must be considered rather than potentially diagnosing two different viral causes to explain the same symptoms.

Numerous other respiratory infections have been diagnosed in Covid positive patients. We do not know the risk of these infections causing a false positive Covid result. The majority of viruses that cause flu-like illnesses show a pattern of contagion and, sadly, result in hospital admissions, ITU admissions and deaths. Almost all are more common than Covid at this time of year. There is a real risk of the UK mislabelling these other respiratory infections as Covid and thereby exaggerating the Covid problem – this has not received sufficient scientific attention.

This paper suggests one simple policy takeaway.

Given the risk of false positive results for Covid testing, an outbreak should not be diagnosed in a low prevalence area in the absence of one of two Covid specific indicators: loss of smell or characteristic chest CT findings. Having accurately established outbreaks, it is safe to switch to more sensitive testing of direct contacts.

Identifying every case should not be the aim in areas with low disease prevalence because of the problem of false positive results. Instead, the focus should be on accurate identification of every outbreak of Covid. Loss of smell is seen in around 65% of genuine Covid cases but statistically loss of smell would be seen in 96% of genuine outbreaks with three people or more. Where there is new onset loss of smell (or chest CT evidence) combined with positive testing, the chances of misdiagnosis are vanishingly small.

Covid in young adults

Why are we seeing alleged excess Covid-like cases in people in their 20s. The narrative is the same across Europe: that a new surge in Covid cases is being driven by young adults. This is despite the fact that during the spring epidemic, symptomatic outbreaks were focused on nursing homes and hospitals. Large numbers of symptomatic young people were not observed in the spring. Why are they being seen now? Why would the impact of the virus at a population level be so different now to what it was in the spring?

Real Covid cases lead, after a time, to rising antibody levels. The percentage of 20-29 year olds with antibodies to Covid has not risen between June and 6th September. It has actually fallen, as it has for the rest of the population. There is a serious inconsistency with the widely accepted hypothesis that the recent surge of flu-like illness must be Covid and the steady continued drop in Covid antibody levels throughout the population. The latter is scientifically provable, the former remains only a hypothesis.

Epidemics spread fast and cluster geographically. Where recent epidemic outbreaks of actual Covid have been mapped, such as in Florida and Marseille, the spread from young adults to other age groups happened within a week and within two weeks Covid was detected in every age group. Given that the time from diagnosis to death is approximately 20 days then a rise in deaths was seen approximately 27 days after new cases in young adults.

The UK data demonstrates that the rise in alleged-Covid cases in young people from the beginning of August did not reach other age groups for a full month. Also, the data since mid Sept has not shown the expected consequent increase in deaths in the UK from the August surge. It seems the outcomes from the UK surge in flu-like illnesses in August does not appear to match that seen in recent genuine Covid outbreaks. This is puzzling, and must make us more cautious.

Some might argue that vulnerable groups have been successfully shielded in the UK and this could explain the lack of deaths now in the UK. Are we better at shielding than Florida and Marseille. Have we successfully hermetically sealed 15-25 year olds from vulnerable groups? It is not obvious that we have shielded any more successfully than other countries. If we have not shielded more successfully, then why has our death rate not increase. like other countries? Death rates should have already increased if this outbreak is Covid rather than other flu-like viruses.

The percentage of young people testing positive for Covid remains low, at a few percent of those tested. Although the false positive rate for Covid testing has not been definitively established, the rate we are observing in the young in the UK is low enough that we cannot exclude the possibility that they are almost all Covid false positives. To differentiate real Covid from false positives requires careful thought and more thorough assessment and testing of those cases. It is essential that loss of smell and Chest CT confirmation is used to confirm where there are genuine outbreaks.

Glandular fever: a case study

This short paper suggests that the global focus on Covid may have skewed our diagnostic capabilities. There are many flu-like illnesses that cause similar symptoms. Let us consider one of them, purely as a case study, and explore how difficult it remains for those who are charged with addressing these issues to track what is really going on. I have chosen a common but fairly serious flu-like illness with which many readers will be familiar: glandular fever.

As it happens, the August data in the UK can be read as consistent with an outbreak of glandular fever, although it is far too soon to be remotely definitive. What is striking about the age distribution is that 2-10 yr olds and 15-25 yr olds were being affected at a higher rate than 10-15 year olds. This is a very unusual distribution, but it is the exact same distribution as seen for glandular fever, which is caused by another virus: EBV.

EBV infection is spread by saliva. It affects drooling toddlers sharing their toys. It also spreads by 15 to 25 year olds kissing. Thereafter, the virus can still be detected in the tonsils of older adults but it is kept under control by an active immune system. In those with a compromised immune system, the virus can reactivate and even be lethal.

The symptoms of glandular fever are fatigue, fever, sore throat, nausea and loss of appetite and a dry cough. Enlarged lymph nodes and spleen are also common findings and these distinguishing signs have not been reported in Covid. If the correct diagnosis is EBV, there would be no loss of smell and no characteristic CT chest findings seen in Covid patients. Unfortunately, there is no sign that the outbreaks of patients testing positive for Covid are being consistently cross-checked with loss of smell and CT chest scans across the UK, or indeed globally. Thus, this outbreak could be EBV, it could be some other virus that causes flu-like illness, or it could be Covid. No one knows whilst the risk of false positive testing in the presence of these viruses is still so unexplored.

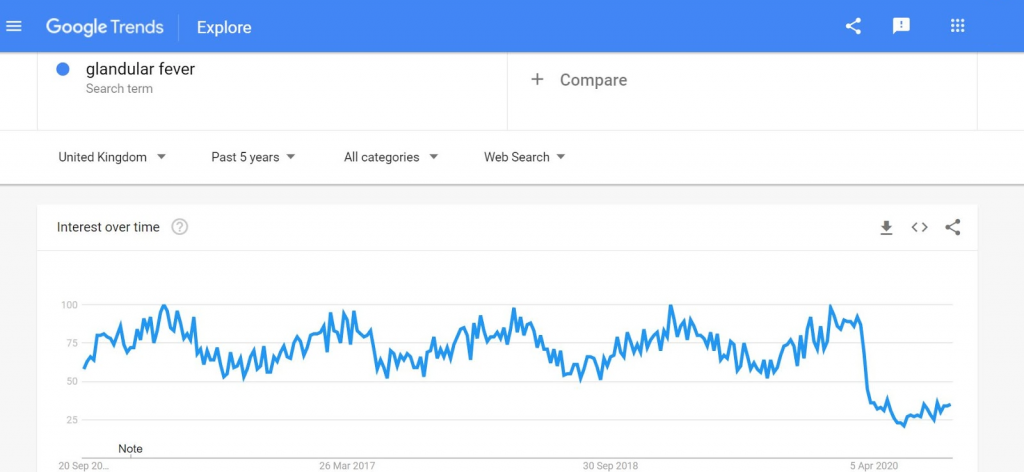

Importantly, the frequency of glandular fever cases starts increasing in August as it is a seasonal virus. Searches on Google for “Glandular fever” over a number of years show a clear seasonality but fell to a new low in April 2020 since when it seems as though every fever has been considered by the general public searching Google to be Covid unless proven otherwise.

Could EBV cause a positive Covid test?

It is one thing to contemplate the possibility that EBV infections, or other viruses that cause flu-like infections, are being misdiagnosed as Covid because of the similarity of physical symptoms. It is quite another to go further and consider whether EBV, itself, or other viruses, could cause false positive Covid tests.

When a new test is brought to market it has to undergo quality control to ensure it is safe. For Covid, there was huge urgency to make a test available and, through massive effort, a test was worked up and approved rapidly. Manufacturers checked that samples of other non-Covid viruses and bacteria could not produce a positive test. Cross reactivity like this is a known cause of false positive test results and must be eliminated for effective testing. Samples of as many different viruses and bacteria as possible were tested and none gave a false positive result. The efforts of those involved in this work should not be underestimated and testing was invaluable in the early stages of the epidemic to reduce spread.

Having passed the manufacturer’s checks, the laboratories undertaking testing would have repeated this work with their own samples. Again, the aim was to find a range of different samples to check for cross-reactivity. In every case, the Covid test was cross-checked against only one sample of each type of virus or bacteria. In May, the Royal College of Pathologists published guidelines recommending that 30-40 samples of other viruses should be tested by manufacturers to validate the test and 10-20 for the laboratories to verify safety. That is single samples of up to 20 different virus types. If every EBV sample, for example, resulted in a positive Covid test then the test would have to be altered to prevent that risk.

However, the same test is now being used in a totally different way. Rather than testing symptomatic patients at a time of exponential spread, we are screening large swathes of the population who have self-selected based on a huge range of sometimes very mild symptoms. The checks required for mass population screening have been totally bypassed. The crucial point to note is that just because a single sample of EBV does not trigger a false positive result, that does not mean that the EBV virus never triggers a false positive result. An EBV-generated false-positive could happen 5% of the time, 1% of the time or 0.01% of the time. When testing small numbers of symptomatic people this does not matter. When testing 200,000 people every day for Covid, the risk of EBV-generated false positives (or other false positives from other viruses) potentially start to matter a very great deal.

The UK has now done 20 million tests and continues to test over 200,000 a day. It is not known whether there are other viruses that can mistakenly generate a positive Covid test result on rare occasions. When testing at the rate we are, even a 5% chance of producing false positives from other viruses in this way becomes highly significant, especially if there are co-infections. Recall that the EQA studies found 0.6-1% false positives with related coronaviruses. Checking a few samples of EBV when devising a new Covid test only provides reassurance that mistakes will not happen with every case of EBV.

But when you have a national screening programme that tests every cough, splutter or sneeze we need to know what percentage of those cases may test (falsely) positive for Covid. For example, in order to demonstrate that 5% of EBV cases will produce a false positive Covid test, hundreds of EBV samples would need to be checked. If 0.5% of EBV cases cause a false positive Covid result then thousands of samples, not tens of samples, would need to be tested. The original testing was on tens of samples. This is not a criticism of the original testing which was urgent and completed with admirable speed.

Because this work has not been done, we cannot know whether there is a problem with potential EBV false positives (or other viruses circulating in the population) or not. It would be a huge challenge to find adequate numbers of EBV samples in order to check – especially as samples would need to have been taken before Covid to avoid any suggestion that a positive result was in fact a genuine Covid case.

Is there any evidence at all that EBV cases are being wrongly diagnosed as Covid cases? There have been several publications of Covid and EBV ‘co-infections’. These often describe features of EBV infection in young people with no diagnostically specific features of Covid infection but a positive Covid test result is treated as being definitive. (Examples: here, here and here). A study in Wuhan of 67 patients with Covid in January, when disease prevalence was relatively low, found more than half had antibodies demonstrating a recent EBV infection.

Given the difficulty of testing hundreds of EBV samples with the Covid test, we must instead test the EBV-generated false positive hypothesis by examining the patients themselves more closely. Centralised testing results should not prevent doctors from trying to correctly diagnose the patient in front of them. How many of the current population testing Covid positive are also EBV positive? How many have enlarged lymph nodes and spleen characteristic of EBV infection rather than Covid? What proportion of them have lost their sense of smell or have characteristic chest CT findings. How many of them, given time, have detectable antibodies to Covid?

EBV is an easy-to-understand example of an infective agent that could cause false positive results. I must emphasise that the discussion of EBV in this paper is just one example of the type of complicated viral universe in which Covid is operating and making life very difficult for scientists. The UK now has a national screening programme testing every case of glandular fever, every high temperature, every cough, with no understanding of what proportion of these cases will, in the absence of Covid, be a false positive Covid result. When testing more than 200,000 mostly symptomatic patients a day, even a miniscule proportion of EBV or other flu-like illnesses causing a false positive Covid test result could be a very serious problem.

Conclusion

Diagnosis needs to be more specific. During periods of low Covid prevalence, a positive Covid test result should not be enough to diagnose a genuine Covid outbreak unless it is accompanied by loss of smell and/or distinctive Chest CT results in the original patient and at least one of their direct contacts. Using loss of smell as a gateway to testing will free up capacity for intensive Test and Trace work where there are real outbreaks of Covid.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpAIDS Hysteria Prefigured Covid hysteria

Next PostLatest News