by James Ferguson

Are you positive you are ‘positive’?

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do sir?” – John Maynard Keynes

The UK has a big problem with the false positive rate (FPR) of its COVID-19 tests. The authorities acknowledge no FPR, so positive test results are not corrected for false positives and that is a big problem.

The standard COVID-19 RT-PCR test results have a consistent positive rate of ≤ 2% which also appears to be the likely false positive rate (FPR), rendering the number of official ‘cases’ virtually meaningless. The likely low virus prevalence (~0.02%) is consistent with as few as 1% of the 6,100+ Brits now testing positive each week in the wider community (pillar 2) tests actually having the disease.

We are now asked to believe that a random, probably asymptomatic member of the public is 5x more likely to test ‘positive’ than someone tested in hospital, which seems preposterous given that ~40% of diagnosed infections originated in hospitals.

The high amplification of PCR tests requires them to be subject to black box software algorithms, which the numbers suggest are preset at a 2% positive rate. If so, we will never get ‘cases’ down until and unless we reduce, or better yet cease altogether, randomized testing. Instead the government plans to ramp them up to 10m a day at a cost of £100bn, equivalent to the entire NHS budget.

Government interventions have seriously negative political, economic and health implications yet are entirely predicated on test results that are almost entirely false. Despite the prevalence of virus in the UK having fallen to about 2-in-10,000, the chances of testing ‘positive’ stubbornly remain ~100x higher than that.

First do no harm

It may surprise you to know that in medicine, a positive test result does not often, or even usually, mean that an asymptomatic patient has the disease. The lower the prevalence of a disease compared to the false positive rate (FPR) of the test, the more inaccurate the results of the test will be. Consequently, it is often advisable that random testing in the absence of corroborating symptoms, for certain types of cancer for example, is avoided and doubly so if the treatment has non-trivial negative side-effects. In Probabilistic Reasoning in Clinical Medicine (1982), edited by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his long-time collaborator Amos Tversky, David Eddy provided physicians with the following diagnostic puzzle. Women age 40, participate in routine screening for breast cancer which has a prevalence of 1%. The mammogram test has a false negative rate of 20% and a false positive rate of 10%. What is the probability that a woman with a positive test actually has breast cancer? The correct answer in this case is 7.5% but 95/100 doctors in the study gave answers in the range 70-80%, i.e. their estimates were out by an order of magnitude. [The solution: in each batch of 100,000 tests, 800 (80% of the 1,000 women with breast cancer) will be picked up; but so too will 9,920 (10% FPR) of the 99,200 healthy women. Therefore, the chance of actually being positive (800) if tested positive (800 + 9,920 = 10,720) is only 7.46% (800/10,720).]

Conditional probabilities

In the section on conditional probability in their new book Radical Uncertainty, Mervyn King and John Kay quote a similar study by psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer of the Max Planck Institute and author of Reckoning with Risk, who illustrated medical experts’ statistical innumeracy with the Haemoccult test for colorectal cancer, a disease with an incidence of 0.3%. The test had a false negative rate of 50% and a false positive rate of 3%. Gigerenzer and co-author Ulrich Hoffrage asked 48 experienced (average 14 years) doctors what the probability was that someone testing positive actually had colorectal cancer. The correct answer in this case is around 5%. However, about half the doctors estimated the probability at either 50% or 47%, i.e. the sensitivity (FNR) or the sensitivity less the specificity (FNR – FPR) respectively. [The solution: from 100,000 test subjects, the test would correctly identify only half of the 300 who had cancer but also falsely identify as positive 2,991 (3%) of the 99,700 healthy subjects. This time the chance of being positive if tested positive (150 + 2,991 = 3,141) is 4.78% (150/3,141).]As Gigerenzer concluded in a subsequent paper in 2003, “many doctors have trouble distinguishing between the sensitivity (FNR), the specificity (FPR), and the positive predictive value (probability that a positive test is a true positive) of test —three conditional probabilities.” Because doctors and patients alike are inclined to believe that almost all ‘positive’ tests indicate the presence of disease, Gigerenzer argues that randomised screening is far too poorly understood and too inaccurate in the case of low incidence diseases and can prove harmful where interventions have non-trivial, negative side-effects. Yet this straightforward lesson in medical statistics from the 1990s has been all but forgotten in the COVID-19 panic of 2020. Whilst false negatives might be the major concern if a disease is rife, when the incidence is low, as with the specific cancers above or COVID-19 PCR test, for example, the overriding problem is the false positive rate (FPR). There have been 17.6m cumulative RT-PCR (antigen) tests in the UK, 350k (2%) of which gave positive results. Westminster assumes this means the prevalence of COVID-19 is about 2% but that conclusion is predicated on the tests being 100% accurate which, as we will see below, is not the case at all.

Positives ≠ cases

One clue is that this 2% positive rate crops up worryingly consistently, even though the vast majority of those tested nowadays are not in hospital, unlike the early days. For example, from the 520k pillar 2 (community) tests in the fortnight around the end of May, there were 10.5k positives (2%), in the week ending June 24th there were 4k positives from 160k pillar 2 tests (2%) and last week about 6k of the 300k pillar 2 tests (2% again) were also ‘positive’. There are two big problems with this. First, medically speaking, a positive test result is not a ‘case’. A ‘case’ is by definition both symptomatic and must be diagnosed by a doctor but few of the pillar 2 positives report any symptoms at all and almost none are seen by doctors. Second, NHS diagnosis, hospital admission and death data have all declined consistently since the peak, by over 99% in the case of deaths, suggesting it is the ‘positive’ test data that have been corrupted. The challenge therefore is to deduce what proportion of the reported ‘positives’ actually have the disease (i.e. what is the FPR)? Bear in mind two things. First, the software that comes with the PCR testing machines states that these machines are not to be used for diagnostics (only screening). Second, the positive test rate can never be lower than the FPR.

Is UK prevalence now 0.02%?

The epidemiological rule-of-thumb for novel viruses is that medical cases can be assumed to be about 10x deaths and infections 10x cases. Note too that by medical cases what is meant is symptomatic hospitalisations not asymptomatic ‘positive’ RT-PCR test results. With no reported FPR to analyse and adjust reported test positives with, but with deaths now averaging 7 per day in the UK, we can backwardly estimate 70 daily symptomatic ‘cases’. This we can roughly corroborate with NHS diagnoses, which average 40 per day in England (let’s say 45 for the UK as a whole). The factor 10 rule-of-thumb therefore implies 450-700 new daily infections. UK government figures differ from the NHS and daily hospital admissions are now 84, after peaking in early April at 3,356 (-97.5%). Since the infection period lasts 22-23 days, the official death and diagnosis data indicate roughly 10-18k current active infections in the UK, 90% of whom feel just fine. Even the 2k daily pillar 1 (in hospital) tests only result in about 80 (0.4%) positives, 40 diagnoses and 20 admissions. Crucially, all these data are an order of magnitude lower than the positive test data and result in an inferred virus prevalence of 0.015%-0.025% (average 0.02%), which is far too low for randomized testing with anything less than a 100% perfect test; and the RT-PCR test is certainly less than 100% perfect.

Only 1% of ‘positives’ are positive

So, how do we reconcile an apparent prevalence of around 0.02% with a consistent positive PCR test rate of around 2%, which is some 100x higher? Because of the low prevalence of the disease, reported UK pillar 2 positives rate and the FPR are both about 2%, meaning almost all ‘positive’ test results are false with an overall error rate of 99:1 (99 errors for each correct answer). In other words, for each 100,000 people tested, we are picking up at least 24 of the 25 (98%) true positives but also falsely identifying 2,000 (2%) of the 99,975 healthy people as positives too. Not only do < 1.2% (24/2024) of pillar 2 ‘positives’ really have COVID-19, of which only 0.1% would be medically defined as symptomatic ‘cases’, but this 2% FPR rate also explains the ~2% (2.02% in this case) positive rate so consistently observed in the official UK data.

The priority now: FPR

This illustrates just how much the FPR matters and how seriously compromised the official data are without it. Carl Mayers, Technical Capability Leader at the Ministry of Defence Science and Technology Laborartory (Dstl) at Porton Down, is just one government scientist who is understandably worried about the undisclosed FPR. Mayers and his co-author Kate Baker submitted a paper at the start of June to the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) noting that the RT-PCR assays used for testing in the UK had been verified by Public Health England (PHE) “and show over 95% sensitivity and specificity” (i.e. a sub-5% false positive rate) in idealized laboratory conditions but that “we have been unable to find any data on the operational false positive rate” (their bold) and “this must be measured as a priority” (my bold). Yet SAGE minutes from the following day’s meeting reveal this paper was not even discussed.

False positives

According to Mayers, an establishment insider, PHE is aware the COVID-19 PCR test false positive rate (FPR) may be as high as 5%, even in idealized ‘analytical’ laboratory environments. Out in the real world though, ‘operational’ false positives are often at least twice as likely to occur: via contamination of equipment (poor manufacturing) or reagents (poor handling), during sampling (poor execution), ‘aerosolization’ during swab extraction (poor luck), cross-reaction with other genetic material during DNA amplification (poor design specification), and contamination of the DNA target (poor lab protocol), all of which are aggravating factors additional to any problems inherent in the analytic sensitivity of the test process itself, which is itself far less binary than the policymakers seem to believe. As if this wasn’t bad enough, over-amplification of viral samples (i.e. a cycle threshold ‘Ct’ > 30) causes old cases to test positive, at least 6 weeks after recovery when people are no longer infectious and the virus in their system is no longer remotely viable, leading Jason Leitch, Scotland’s National Clinical Director to call the current PCR test ‘a bit rubbish.’

Test…

The RT-PCR swab test looks for the existence of viral RNA in infected people. Reverse Transcription (RT) is where viral RNA is converted into DNA, which is then amplified (doubling each cycle) in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A primer is used to select the specific DNA and PCR works on the assumption that only the desired DNA will be duplicated and detected. Whilst each repeat cycle increases the likelihood of detecting viral DNA, it also increases the chances that broken bits of DNA, contaminating DNA or merely similar DNA may be duplicated as well, which increases the chances that any DNA match found is not from the Covid viral sequence.

…and repeat

Amplification makes it easier to discover virus DNA but too much amplification makes it too easy. In Europe the amplification, or ‘cycle threshold’ (Ct), is limited to 30Ct, i.e. doubling 30x (2 to the power of 30 = 1 billion copies). It has been known since April, that even apparently heavy viral load cases “with Ct above 33-34 using our RT-PCR system are not contagious and can thus be discharged from hospital care or strict confinement for non-hospitalized patients.” A review of 25 related papers by Carl Heneghan at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) also has concluded that any positive result above 30Ct is essentially non-viable even in lab cultures (i.e. in the absence of any functional immune system), let alone in humans. However, in the US, an amplification of 40Ct is common (1 trillion copies) and in the UK, COVID-19 RT-PCR tests are amplified by up to 42Ct. This is 2 to the power of 42 (i.e. 4.4 trillion copies), which is 4,400x the ‘safe’ screening limit. The higher the amplification, the more likely you are to get a ‘positive’ but the more likely it is that this positive will be false. True positives can be confirmed by genetic sequencing, for example at the Sanger Institute, but this check is not made, or at least if it is, the data is also unreported.

The sliding scale

Whatever else you may therefore have previously thought about the PCR COVID-19 test, it should be clear by now that it is far from either fully accurate, objective or binary. Positive results are not black or white but on a sliding scale of grey. This means labs are required to decide, somewhat subjectively, where to draw the line because ultimately, if you run enough cycles, every single sample would eventually turn positive due to amplification, viral breakdown and contamination. As Marianne Jakobsen of Odense University Hospital Denmark puts it on UgenTec’s website: “there is a real risk of errors if you simply accept cycler software calls at face value. You either need to add a time-consuming manual review step, or adopt intelligent software.”

Adjusting Ct test results

Most labs therefore run software to adjust positive results (i.e. decide the threshold) closer to some sort of ‘expected’ rate. However, as we have painfully discovered with Prof. Neil Ferguson’s spectacularly inaccurate epidemiological model (expected UK deaths 510,000; actual deaths 41,537) if the model disagrees with reality, some modelers prefer to adjust reality not their model. Software programming companies are no exception and one of them, diagnostics.ai, is taking another one UgenTec (which won the no-contest bid for setting and interpreting the Lighthouse Labs thresholds), to the High Court on September 23rd apparently claiming UgenTec had no track record, external quality assurance (EQA) or experience in this field. Whilst this case may prove no more than sour grapes on diagnostics.ai’s part, it does show that PCR test result interpretation, whether done by human or computer, is ultimately not only subjective but as such will always effectively bury the FPR.

Increase tests, increase ‘cases’

So, is it the software that is setting the UK positive case rate ≤ 2%? Because if it is, we will never get the positive rate below 2% until we cease testing asymptomatics. Last week (ending August 26th) there were just over 6,122 positives from 316,909 pillar 2 tests (1.93%), as with the week of July 22nd (1.9%). Pillar 2 tests deliver a (suspiciously) stable proportion of positive results, consistently averaging ≤ 2%. As Carl Heneghan at the CEBM in Oxford has explained, the increase in absolute number of pillar 2 positives is nothing more than a function of increased testing, not increased disease as erroneously reported in the media. Heneghan shows that whilst pillar 1 cases per 100,000 tests have been steadily declining for months, pillar 2 cases per 100,000 tests are “flatlining” (at around 2%).

30,000 under house arrest

In the week ending August 26th, there were 1.45m tests processed in the UK across all 4 pillars, though there seem to be no published results for the 1m of these tests that were pillar 3 (antibody tests) or pillar 4 “national surveillance” tests (NB. none of the UK numbers ever seem to match up). But as far as pillar 1 (hospital) cases are concerned, these have fallen by about 90% since the start of June, so almost all positive cases now reported in the UK (> 92% of the total) come from the largely asymptomatic pillar 2 tests in the wider community. Whilst pillar 2 tests were originally intended to be only for the symptomatic (doctor referral etc) the facilities have been swamped with asymptomatics wanting testing, and their numbers are only increasing (+25% over the last two weeks alone) perhaps because there are now very few symptomatics out there. The proportion of pillar 2 tests that that are taken by asymptomatics is yet another figure that is not published but there are 320k pillar 2 tests per week, whilst the weekly rate of COVID-19 diagnoses by NHS England is just 280. Assume that Brits are total hypochrondriacs and only 1% of those reporting respiratory symptoms to their doctor (who sends them out to get a pillar 2 test) end up diagnosed, that still means well over 90% of all pillar 2 tests are taken by the asymptomatic; and asymptomatics taking PCR tests when the FPR is higher than the prevalence (100x higher in this instance) results in a meaningless FPR (of 99% in this instance).Believing six impossible things before breakfast

Whilst the positive rate for pillar 2 is consistently ~2% (with that suspiciously low degree of variability), it is more than possible that the raw data FPR is 5-10% (consistent with the numbers that Carl Mayers referred to) and the only reason we don’t see such high numbers is that the software is adjusting the positive threshold back down to 2%. However, if that is the case, no matter what the true prevalence of the disease, the positive count will always and forever be stuck at ~2% of the number of tests. The only way to ‘eradicate’ COVID-19 in that case would be to cease randomized testing altogether, which Gerd Gigerenzer might tell you wouldn’t be a bad idea at all. Instead, lamentably, the UK government is reportedly doubling down with its ill-informed ‘Operation Moonshot’, an epically misguided plan to increase testing to 10m/day, which would obviously mean almost exclusively asymptomatics, and which we can therefore confidently expect to generate an apparent surge in positive ‘cases’ to 200,000 a day, equivalent to the FPR and proportionate to the increase in the number of tests.

Emperor’s new clothes

Interestingly, though not in a good way, the positive rate seems to differ markedly depending on whether we are talking about pillar 1 tests (mainly NHS labs) or pillar 2 tests, mainly managed by Deloitte (weird but true) which gave the software contract to UgenTec and which between them set the ~2% positive thresholds for the Lighthouse Lab network. This has had the quirky result that a gullible British public is now expected to believe that people in hospital are 4-5x less likely to test positive (0.45%) than fairly randomly selected, largely asymptomatic members of the general public (~2%), despite 40% of transmissions being nosocomial (at hospital). The positive rate, it seems, is not just suspiciously stable but subject to worrying lab-by-lab idiosyncrasies pre-set by management consultants, not doctors. It is little wonder no one is willing to reveal what the FPR is, since there’s a good chance nobody really knows any longer; but that is absolutely no excuse for implying it is zero.

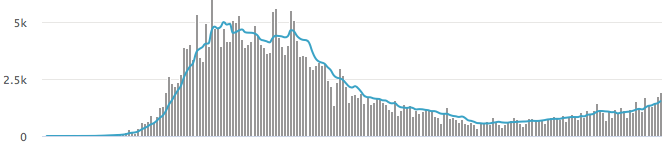

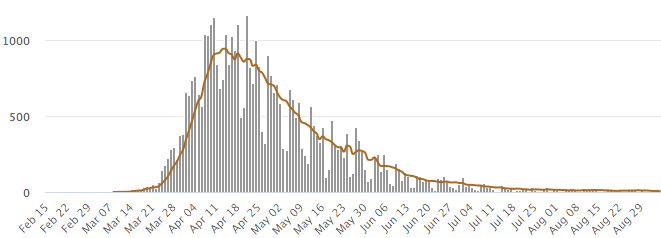

Wave Two or wave goodbye?

The implications of the overt discrepancy between the trajectories of UK positive tests (up) and diagnoses, hospital admissions and deaths (all down) need to be explained. Positives bottomed below 550 per day on July 8th and have since gone up by a factor of three to 1500+ per day. Yet over the same period (shifted forward 12 days to reflect the lag between hospitalisation and death), daily deaths have dropped, also by a factor of three, from 22 to 7, as indeed have admissions, from 62 to 20 (compare the right-hand side of the upper and lower panels in the Chart below). Much more likely, positive but asymptomatic tests are false positives. The Vivaldi 1 study of all UK care home residents found that 81% of positives were asymptomatic, which for this most vulnerable cohort, probably means false positive.

This almost tenfold discrepancy between positive test results and the true incidence of the disease also shows up in the NHS data for 9th August (the most recent available), showing daily diagnoses (40) and hospital admissions (33) in England that are way below the Gov.UK positive ‘cases’ (1,351) and admissions (53) data for the same day. Wards are empty and admissions are so low that I know of at least one hospital (Taunton in Devon), for example, which discharged its last COVID-19 patient three weeks ago and hasn’t had a single admission since. Thus the most likely reason < 3% (40/1351) of positive ‘cases’ are confirmed by diagnosis is the ~2% FPR. Hence the FPR needs to be expressly reported and incorporated into an explicit adjustment of the positive data before even more harm is done.

Occam’s Razor

Oxford University’s Sunetra Gupta believes it is entirely possible that the effective herd immunity threshold (HIT) has already been reached, especially given that there hasn’t been a genuine second wave anywhere. The only measure suggesting higher prevalence than 0.025% is the positive test rate but this data is corrupted by the FPR. The very low prevalence of the disease means that the most rational explanation for almost all the positives (2%), at least in the wider community, is the 2% FPR. This benign conclusion is further supported by the ‘case’ fatality rate (CFR), which has declined 40-fold: from 19% of all ‘cases’ at the mid-April peak to just 0.45% of all ‘positives’ now. The official line is that we are getting better at treating the disease and/or it is only healthy young people getting it now; but surely the far simpler explanation is the mathematically supported one that we are wrongly assuming, against all the evidence, that the PCR test results are 100% accurate.

Fear and confusion

Deaths and hospitalizations have always provided a far truer, and harder to misrepresent, profile of the progress of the disease. Happily, hospital wards are empty and deaths had already all but disappeared off the bottom of the chart (lower panel, in the chart above) as long ago as mid/late July; implying the infection was all but gone as long ago as mid-June. So, why are UK businesses still facing restrictions and enduring localized lockdowns and 10pm curfews (Glasgow, Bury, Bolton and Caerphilly)? Why are Brits forced to wear masks, subjected to traveler quarantines and, if randomly tested positive, forced into self-isolation along with their friends and families? Why has the UK government listened to the histrionics of discredited self-publicists like Neil Ferguson (who vaingloriously and quite sickeningly claims to have ‘saved’ 3.1m lives) rather than the calm, quiet and sage interpretations offered by Oxford University’s Sunetra Gupta, Cambridge University’s Sir David Spiegelhalter, the CEBM’s Carl Heneghan or Porton Down’s Carl Mayers? Let’s be clear: it certainly has nothing to do with ‘the science’ (if by science we mean ‘math’); but it has a lot to do with a generally poor grasp of statistics in Westminster; and even more to do with political interference and overreach.

Bad Math II

As an important aside, it appears that the whole global lockdown fiasco might have been caused by another elementary mathematical mistake from the start. The case fatality rate (CFR) is not to be confused with the infection fatality rate (IFR), which is usually 10x smaller. This is epidemiology 101. The epidemiological rule-of-thumb mentioned above is that (mild and therefore unreported) infections can be initially assumed to be approximately 10x cases (hospital admissions) which are in turn about 10x deaths. The initial WHO and CDC guidance following Wuhan back in February was that COVID-19 could be expected to have the same 0.1% CFR as flu. The mistake was that 0.1% was flu’s IFR, not its CFR. Somehow, within days, Congress was then informed on March 11th that the estimated mortality for the novel coronavirus was 10x that of flu and days after that, the lockdowns started.

Neil Ferguson: Covid’s Matthew Hopkins

This slip-of-the-tongue error was, naturally enough, copied, compounded and legitimized by the notorious Prof. Neil Ferguson, who referenced a paper from March 13th he had co-authored with Verity et al. which took “the CFR in China of 1.38% (to) obtain an overall IFR estimate for China of 0.66%”. Not three days later his ICL team’s infamous March 16th paper further bumped up “the IFR estimates from Verity et al… to account for a non-uniform attack rate giving an overall IFR of 0.9%.” Just like magic, the IFR implied by his own CFR estimate of 1.38% had, without cause, justification or excuse, risen 6.5-fold from his peers’ rule-of-thumb of 0.14% to 0.9%, which incidentally meant his mortality forecast would also be similarly multiplied. Not satisfied with that, he then exaggerated terminal herd immunity.

Compounding errors

Because Ferguson’s model simplistically assumed no natural immunity (there is) and that all socialization is homogenous (it isn’t), his model doesn’t anticipate herd immunity until 81% of the population has been infected. All the evidence since as far back as February and the Diamond Princess indicated that effective herd immunity is occurring around a 20-25% infection rate; but the modelers have still not updated their models to any of the real world data yet and I don’t suppose they ever will. This is also why these models continue to report an R of ≥ 1.0 (growth) when the data, at least on hospital admissions and deaths, suggest the R has been 0.3-0.6 (steadily declining) since March. Compound all these errors and Ferguson’s expected UK death toll of 510k has proved to be 12x too high. His forecast of 2.2m US deaths has also, thankfully but no thanks to him, been 11x too high too. The residual problem is that the politicians still believe this is merely Armageddon postponed, not Armageddon averted. “A coward dies a thousand times before his death, but the valiant taste of death but once” (Shakespeare).

Quality control

It is wholly standard to insist on external quality assurance (EQA) for any test but none such has been provided here. Indeed all information is held back on a need-to-know rather than a free society basis. The UK carried out 1.45m tests last week but published the results for only 452k of them. No pillar 3 (antibody) test results have been published at all, which begs the question: why not (official reason – the data has been anonymized, as if that makes any sense)? The problem is that instead of addressing the FPR, the authorities act as if it is zero, and so assume relatively high virus prevalence. If however, the 2% positive rate is merely a reflection of the FPR, a likely explanation for why pillar 3 results remain unpublished might be that they counterintuitively show a decline in antibody positives. Yet this is only to be expected if the prevalence is both very low and declining. T-cells retain the information to make antibodies but if there is no call for them because people are no longer coming into contact with infections, antibodies present in the blood stream decline. Why there are no published data on pillar 4 (‘national surveillance’ PCR tests remains a mystery).

It’s not difficult

However, it is relatively straightforward to resolve the FPR issue. The Sanger Institute is gene sequencing positive results but will fail to achieve this with any false positives, so publishing the proportion of failed sequencing samples would go a long way to answering the FPR question. Alternatively, we could subject positive PCR tests to a protein test for confirmation. Lab contaminated and/or previously-infected-now-recovered samples would not be able to generate these proteins like a live virus would, so once again, the proportion of positive tests absent protein would give us a reliable indication of the FPR.

Scared to death

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has filtered four facts from the international COVID-19 experience and these are: that the growth in daily deaths declines to zero within 25-30 days, that they then decline, that this profile is ubiquitous and so much so that governmental non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) made little or no difference. The UK government needs to understand that neither assuming that ‘cases’ are growing, without at least first discounting the possibility that what is observed is merely a property of the FPR, nor ordering anti-liberal NPIs, is in any way ‘following the science’. Even a quite simple understanding of statistics indicates that positive test results must be parsed through the filter of the relevant FPR. Fortunately, we can estimate the FPR from what little raw data the government has given us but worryingly, this estimate suggests that ~99% of all positive tests are ‘false’. Meanwhile, increased deaths from drug and alcohol abuse during lockdowns, the inevitable increase in cases of depression and suicide once job losses after furlough, business and marriage failures post loan forbearance become manifest and, most seriously, the missed cancer diagnoses from the 2.1m screenings that have been delayed must be balanced against a government response to COVID-19 that looks increasingly out of all proportion to the hard evidence. The unacknowledged FPR is taking lives, so establishing the FPR, and therefore accurate numbers for the true community prevalence of the virus, is absolutely essential.

James Ferguson is the Founding Partner of MacroStrategy

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostLatest News