A new study from Public Health England (PHE) and Cambridge University was published in the Lancet last week, claiming to find that the Delta variant “doubles a patients’ risk of hospitalisation compared to the Alpha variant”, as the Telegraph reported (as did the BBC).

Reviewing over 40,000 sequenced positive PCR test results from England between March 29th and May 23rd, 2021, the researchers found that 2.2% of Alpha infections (764/34,656) and 2.3% of Delta infections (196/8,682) were hospitalised within 14 days of their first positive test. However, once they adjusted for factors such as age, ethnicity and vaccination status they found the risk of hospitalisation from Delta more than doubled compared with Alpha (a 2.26-fold increase).

The authors took the opportunity to use the results to stress the importance of being vaccinated, noting that only two per cent of those hospitalised were double vaccinated. However, this data is out of date, as more recent data from the main Delta surge suggests that vaccine efficacy against Delta infection may be as low as 15%.

The finding that Delta is more than twice as serious as Alpha is surprising as official data shows that hospitalisations have been much lower with Delta than Alpha. Data in the PHE technical briefings on the variants of concern shows that between February 1st and August 15th, 2.9% of sequenced Alpha infections resulted in an overnight hospital stay, compared with 1.9% of sequenced Delta infections. Technical Briefing 21 (the most recent) acknowledges this but adds that “a more detailed analysis indicates a significantly greater risk of hospitalisation among Delta cases compared to Alpha (see page 50 of Variant Technical Briefing 15)”.

Technical Briefing 15 quotes the findings, then in pre-print form, which are now published in the Lancet study (I criticised an earlier version of the claim here).

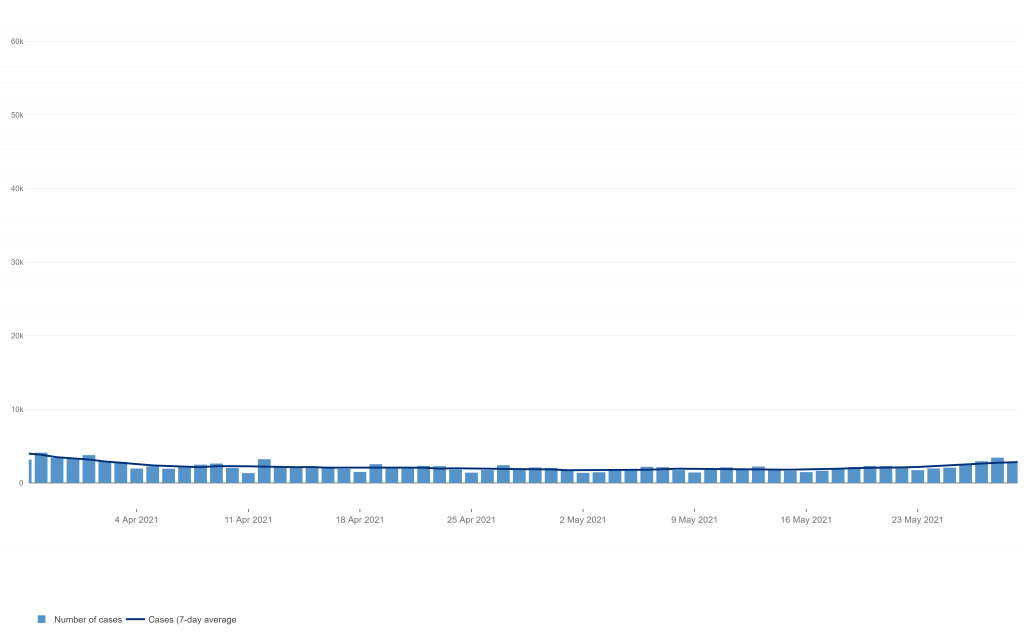

March 29th to May 23rd, the study period, is notable for being a period of low prevalence in England, when there were only around 2,000 reported infections a day (compared to a peak of around 50,000). In the over-60s in that period there were only 100-200 reported infections per day.

This is important because it means that what we are looking at in this study is Alpha as a spent force once it is no longer spreading fast and infecting large numbers of people. In other words, it is an exhausted variant to which herd immunity has been established in the population – which is why it declined sharply from the end of December in England and never resurged as restrictions were lifted. Delta, on the other hand, was the new variant on the block at this point, about to begin its own surge, so at an entirely different epidemiological stage and much more capable of finding susceptible people.

So once again we find PHE comparing the characteristics of a fresh, new variant to an exhausted, old variant and claiming to tell us something absolute about the properties of the two. PHE is still on record from June claiming that Delta is “64% more transmissible” than Alpha, an analysis that only looked at exhausted Alpha versus fresh Delta and failed to spot that Alpha’s secondary attack rate had dropped from 15.1% in December to 10% in May. Delta hit 13.5% in May but never got as high as Alpha’s winter peak rate and has been declining since, dipping below 11% by July.

A similar problem besets the new study. Alpha now may be less serious than Delta, but it’s not a fair comparison as it’s like comparing a pensioner with an athlete.

Look at Technical Briefing 8 from April. There, the case fatality rate of Alpha over the winter (October 1st to March 31st) was stated as 2.3%. This fatality rate is significantly above the hospitalisation rate for Delta in the latest figures of 1.9%, and is the same as the hospitalisation rate for Delta in the new study. On these figures, Alpha in the winter was much more serious than Delta now. It was also much more serious than Alpha post-winter, as its case fatality rate halved after February 1st to 1.2%.

We’re not given variant hospitalisation data prior to February 1st, but the winter surge was dominated by Alpha. Dr Clare Craig has calculated that between December 1st and April 30th the case hospitalisation rate during the Alpha surge was as high as 9%, many times higher than the 2.2% for Alpha quoted in the new study. Since May 1st, corresponding to the Delta surge, it’s been 2.3% (in line with the figures from the study).

A number of factors may have contributed to this lower recent hospitalisation rate: a higher proportion of younger people being infected, protection through vaccination, and the fact that it is summer rather than winter, among others. The study authors evidently agree, which is why their study purports to adjust for these factors to find that, underneath it all, Delta doubles the risk of hospitalisation compared with Alpha.

However, by comparing Delta in its prime to Alpha in its dotage the comparison is not valid and tells us nothing useful. It’s hardly surprising that Delta when new is more serious than Alpha when old – if large numbers of people were still susceptible to Alpha it would have had a resurgence of its own, not died away. But that doesn’t mean Delta is more serious than Alpha was in its winter prime, which is the only relevant comparison – and the one which most people assume is being made.

I would criticise the study authors for being misleading, but it’s not clear to me that those carrying out this research recognise that variants do not have the same epidemiological properties or clinical features when they’re new and when they’re old. This seems to be a crucial lesson about the behaviour of this virus (and presumably other similar viruses) which our ‘experts’ are being very slow at picking up.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

*2 x 0 = 0* – LIES. DAMNED LIES and PHE’s LIES. Updated, useful information and links: https://www.LCAHub.org/

Lies lies lies

Huge Crowds In LONDON Yet MSM Talk About This!! / Hugo Talks #lockdown

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xB7ces6sSE

stand in South Hill Park Bracknell every Sunday from 10am meet fellow anti lockdown freedom lovers, keep yourself sane, make new friends and have a laugh.

(also Wednesdays from 2pm)

Join our Stand in the Park – Bracknell – Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

Really? I’m sure I’ve read this before. A glitch in the Matrix? Better chech the windows and doors aren’t bricked up!

“Injections & Injunctions” Part 1: Paradox | A Conversation with Dr. Robert Malone

https://www.bitchute.com/video/VLjIX18XrrhO/

Corona-Ausschuss S. 67 – Klasse Gespräch mit Dr. med. Sam White, UK – Mutiger Mann!

https://www.bitchute.com/video/jVPwMBRvgnwq/

Yet more bad science and which is regurgitated as a big threat via the MSM – now there’s a shock. It appears (IMHO) that Prof Van Tam’s attendance at the 2019 ‘seminar’ on how to propagandise pandemics was very fruitful.

Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice…sadly, most the public have been fooled unpteen times now.

Dave Cullen covered the ‘event’ I’ve been referring to about 9 months ago in his video on BitChute (and odysee): https://www.bitchute.com/video/Hmxo720ccw4V/

Unfortunately, the original source video which someone found (from Chatham House’s YT page) and re-hosted was mysteriously removed (and their account deleted) by YouTube. Dave’s video coveres the essentialls (the seminar was about 1 hour long).

Very distrubing what they were discussing about doing and that they all seemed to be laughing and joking about it all. Pro VT makes an appearance in the audience (his Belgian counterpart is giving the seminar).

CELEBRITY TRAITORS – THE ROLL CALL OF SHAME

https://www.bitchute.com/video/0gI7iuEMxW3S/

This still puts too much effort into arguing against something which ought to be rejected outright: Between 2021/03/29 and 2021/05/23, there were 143,315 so called cases, ie positive tests results, in total. 40,000 of these, 27.9%, were included in this analysis, or, put the other way round, the majority of cases, 72.08%, were not analysed for some reason.

The authors assume that the hospitalizations frequency among these 34,656 alpha cases is representative of all alpha cases and that the hospitalization frequency of 8682 delta cases must be representative of all delta cases. Nobody bothered to check this based on the existing data. Nobody bothered to rerun this experiment (actually impossible) to determine if the numbers would at come out roughly the same at least once again.

The outcome apparently wasn’t quite what had been hoped for as there was no difference in hospitalization frequencies. Hence, the authors of this text weighed them with all kinds of essentially baseless assumptions about the effects of age, ethnicity and vaccination status (but not comorbidities) and – hey presto – these are finally the droids we were looking for!

This is cargo cult aka junk science at its finest.

Nice Star Wars reference!

You have to question either the abilities or the ethics of the people putting together these NHS ‘reports’, given how often they are so obviously wrong. I mean, we can see thorugh it after looking at data for just a few minutes. Not exactly rocket science either.

They’re just doing what everybody else does. In current times, whoever wants to push a political agenda has a statistic claimed to demonstrate that such is The Science[tm] and that it’s thus not really political.

wtf have they stuck a muzzle on a guy wearing an oxygen mask?

To protect the heroic NHS nurses against his deadly breath, as required by The Science.

As I mentioned the other day about this sort of thing, there are many factors that will play into whether people get seriously ill from COVID or not.

The factor I mentioned about ethnic background and where and how immigrants spent their childhood (i.e what nation and living conditions, diet and health) liekly makes a huge difference to their general health and immune system even today, possibly years or even decades later – exaccerbated if they have dark skin, because of the lesser intensity of sunlight in the UK compared to the likes of Africa and the subcontinent.

Add to these factors one I didn’t think of before that’s related to the above ones, namely that the ‘Delta variant’ was brough back in by and seemingly going around ethnic minority communities from the subcontinent and surrounds.

That surely means that great infection on return to the UK from seeing relatives back in March/April this year meant that transmission was far higher in those communities, which also have far lower take-up of the vaccines.

As a result, that itself skews the study findings because more susceptible people are getting infected. Infection, hospitalisation and death rates (whether we believe them as true or not) given by the NHS have been rising, but it was noticeable to me that those for my area had not really changed except for the number of infections.

Since April, and up until about 5 days ago, NOT ONE person in my borough council area In Herts (135k people approx) has died with or of COVID (as per the way they are shown). Just two have been listed as such since (though they could’ve been added then but died possibly a month ago). From what I hear locally, the two nearest hospitals also aren’t that busy as regards COVID patients.

Sure, vaccination rates (especially in the elderly/vulnerable) are high, but it’s also noticeable that a far larger percentage of the ethnic minority/immigrant population in the area is of Easten European origin, and thus light-skinned/likely to have had better health and diet than those from Africa, the subcontinent, etc).

I’d bet good money that the overwhelming majority of current COVID hospitalisations and deaths are:

I rarely have seen or heard ambulences in my area since April, and recent callouts appear to have been mainly due to a recent spate of car accidents. There also seems to be a relatively quick turnaround on COVID cases here too (under two weeks), which means that the overwhelming majority aren’t serious. Not a peep in the local rag (which was full of COVID scare stories and government COVID propaganda until about May) about COVID in weeks.

Worth looking at the data on NHS England re Deaths, 79% of deaths are in white/british. Lots of decent information to draw objective conclusions from.

https://dailysceptic.org/2021/08/30/the-fatal-flaw-in-phes-new-study-claiming-delta-doubles-risk-of-hospitalisation-compared-to-alpha/#comment-581477

Interesting about the ambulanes. We are about 20 miles from three hospitals so they never did the driving around with blues and twos here as they did in other places.

There’s a steady low level of ambulance activity probably due to all the old folks, and if anything during the “pandemic” it has been even lower than usual, unlike a winter a few years ago when there were fleets of them for a while.

We did get the air ambulance land in the back field but that turned out to be for a kid who was run over in the street. This year there seems to have been more aggressive and ignorant driving, not just the customary Audis, BMWs and Mercs. Post vax? Who knows.

Never let the truth stand in the way of a fairy tale

Oh well hysteria, panic, fear let’s all hide until we starve in our homes.

F’king bar stewards!

And the sheeple aren’t much better. How much life do they need to lose before they get a backbone. Oh here take my child and fill them with your test drugs, no matter they don’t get very ill, please take my child experiment with them.

A hospital stay seems to be defined as an overnight stay. The daughter of a friend called the emergency services at 4am due to breathing problems with Covid. She was discharged just 5 hours later; I suspect it was actually a panic attack, but it is nevertheless a qualifying statistic.

There’s a dichotomy between admissions and discharges. If you are admitted to a ward and discharged from the ward then admissions =discharges. If you attend the ED and are not admitted onto a ward but are discharged home then discharges increment by one, attendances increment by one but admissions remain unaltered. ED attendances are not admissions, but discharges are discharges irrespective. Discharges from the ED have to be treated as any other discharge to ensure that GP letters and any clinic follow ups are sent out.

The Author of this article, which criticises the study has fallen in to the trap of thinking he knows what he is talking about.

Much of the reasoning seems to revolve around his theory being that the alpha variant has become “old and tired”, where as it has actually just become less prevalent, due to the delta variant being more transmissible and itself becoming the dominant strain.

Had the article considered the actual data and methodology of the study and found some substantial error, then there may have been a justification for criticism. But no such analysis is done, so the author’s conclusions should be ignored.

That same delta variant that came from India, which stands at 118th in the world rankings of “covid cases” per million population and 117th for “covid deaths”, both well below the world average? Yeah, that delta’s some bad shit, I tell you. (Just imagine if they’d continued calling it the Indian variant, maybe some people would have started asking questions about just how bad this scariant is.)

Oh, what a tangled web we weave when first we practice the dark art of statisticat analysis.

(With apologies to Scott.)

Thank you, Will, for continuing to take the trouble to dissect the data.

Keeping up with the official stream of misleading stats has exhausted me after 18 months and my eyes now glaze over. Yet we must continue to debunk the data if we are eventually to win this battle.

Not “surprising” but “bullshit”.

The politicians and SAGE are back from their holidays so time to reassert control and continue with the programme of getting the country pharma addicted,

Still comes down to this double narrative Get vaccinated // Immunity is Waning… it cant be both we would have to be in a permanet state of vaccination walking around with infusions for gods sake .So why would i want a vaccine having just heard that people who have been vaccinated in recent months now have a reduced imminity .personalyl i d take my chance on natural immunitty because this state run innoculation does not seem very convncing /Its time the government got a grip on the media instead of giving them free reign to report any old shit.Get the vaccine its good for you or Dont bother its crap, but not both

Just a clarification, but presumably it’s not the virus which has different behaviour between young and old stages of the epidemic cycle (they are genetically identical otherwise would be classed as another variant). The difference is in the host population as early stages there are more susceptible individuals and later more with partial of full immunity due to vaccination or natural herd immunity. Having said that I would expect that over time, new variants would become increasingly more infectious/transmissible, but cause less severe symptoms as this is evolutionarily more advantageous…so SARS-CoV2 will become more like normal common cold coronaviruses

Try telling that to the rest of the Coronpanickers

They understand this. But people who play the lottery also understand that their chances of ever winning anything substantial are zero. They’re just not convinced that it’s actually true. That’s a personality trait which used to be called cowardice in former times: Being paralyzed by risk and thus, falling prey to dangers due to inaction.

Pre-democracy, this wouldn’t have been considered a desirable trait in political leaders or influencers. The shining, recent example for this would Dominic Dumbass who literally fled out of Downing St. 10 in order to hide with his parents(!), despite he certainly rationally new that he had been exposed enough to the dreadful disease that this couldn’t possibly make a difference anymore.

Nevertheless, people are still listening to this guy.

Rxactly what seems to be happening outside of the media.

I wonder if the criteria for hospital admission have been changed to drive up the numbers. I think we all know there will be another lockdown soon despite most deaths NOT being from covid.