There follows a guest post from our in-house doctor, formerly a senior medic in the NHS, who says the widely trailed tsunami of hospitalisations has not only failed to arrive after ‘Freedom Day’, but we seem to be on the downslope of the ‘third wave’.

The philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once remarked: “Life can only be understood backwards, but must be lived forwards.” I have been reflecting on that comment, now we are three weeks since the inappropriately named July 19th ‘Freedom Day’. Readers will remember the cacophony of shrieking from assorted ‘health experts’ prophesying certain doom and a tidal wave of acute Covid admissions that would overwhelm our beleaguered NHS within a fortnight. Representatives from the World Health Organisation described the approach as “epidemiologically stupid”. A letter signed by 1,200 self-defined experts was published in the Lancet predicting imminent catastrophe.

Accordingly, this week I thought I should take a look at how the apocalypse is developing and then make some general observations on the centrality of trust and honesty in medical matters.

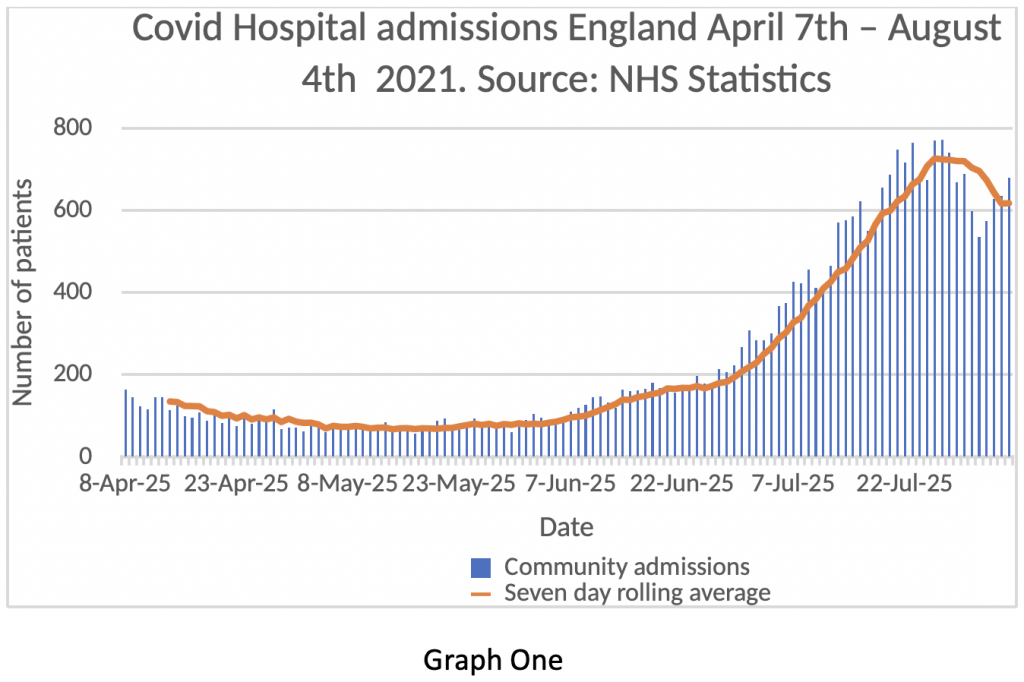

Let’s start with daily admissions to hospitals from the community in Graph One. Daily totals on the blue bars, seven-day rolling average on the orange line. Surprisingly the numbers are lower than on July 19th. How can that be?

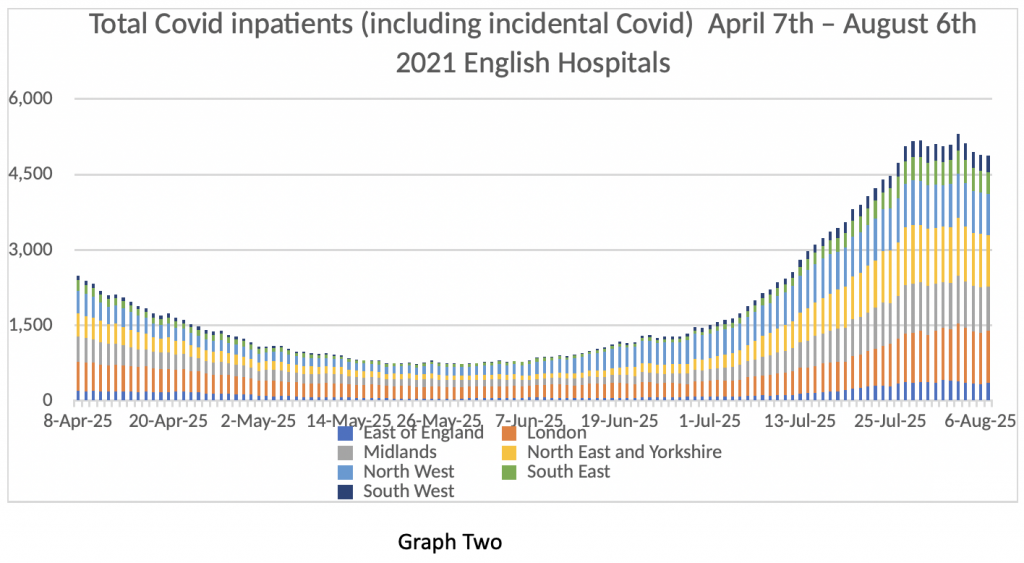

Perhaps there are more patients stacking up in hospitals – sicker patients tend to stay longer and are hard to discharge, so the overall numbers can build up rather quickly. So, Graph Two shows Covid inpatients up to August 5th. Readers should note that Graph Two includes patients suffering from acute Covid (about 75% of the total) plus patients in hospital for non-Covid related illness, but testing positive for Covid (the remaining 25%). How strange – numbers seem to be falling, not rising. This does not fit with the hypothesis – what might explain this anomalous finding?

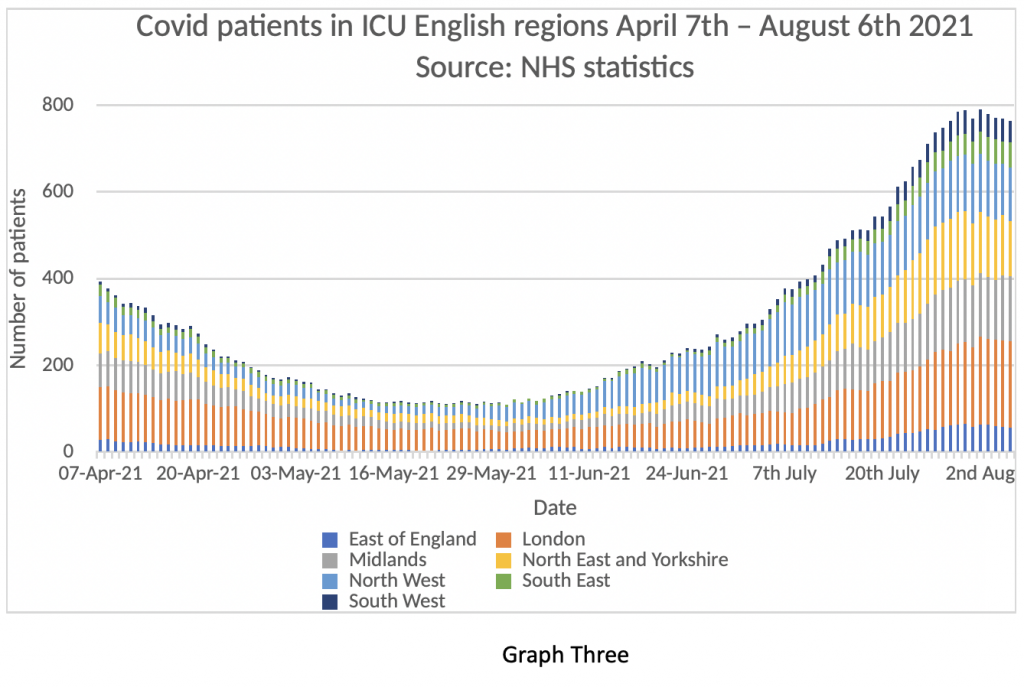

Maybe the numbers of patients in ICU might be on the increase – after all, both the Beta variant and the Delta variant were said to be both more transmissible and more deadly than the Alpha variant. Graph Three shows patients in ICU in English Hospitals up to August 5th. It shows a similar pattern to Graph Two – a small fall in overall patient numbers in the last two weeks. I looked into the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre ICU audit report up to July 30th. This confirms the overall impression from the top line figures. Older patients do not seem to be getting ill with Covid. Over half the admissions to ICU with Covid have body mass indices over 30. Severe illness is heavily skewed to patients with co-morbidities and the unvaccinated. Generally speaking, the patients have slightly less severe illness, shorter stays and lower mortality so far.

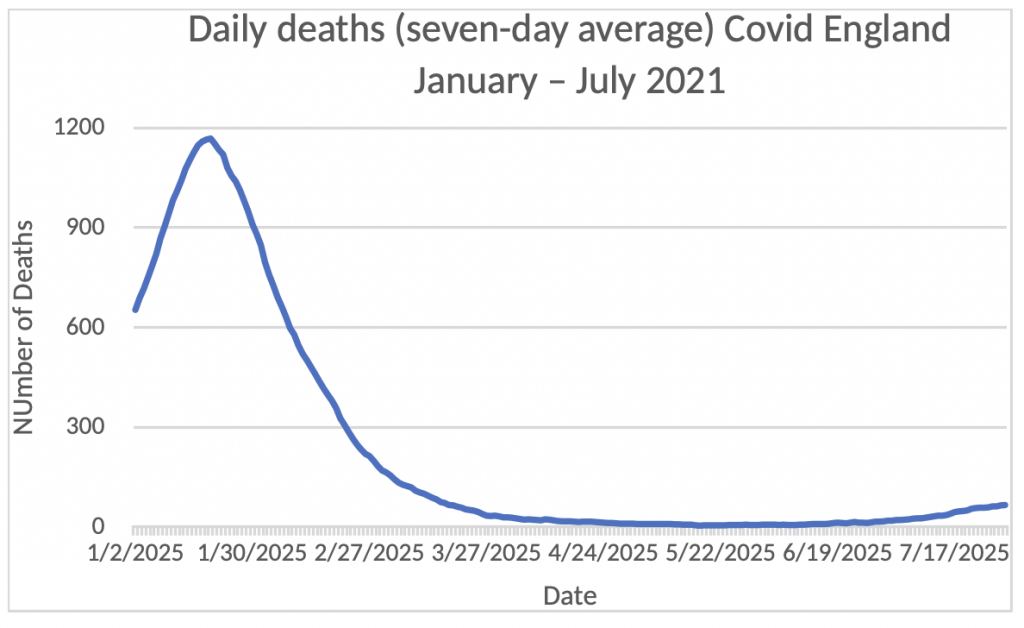

Finally, we look at Covid related deaths since January 1st, 2021, in Graph Four. A barely discernable increase since the beginning of April.

So, whatever is going on with respect to the progress of the pandemic, the widely trailed tsunami of hospitalisations has not arrived yet – in fact, we seem to be on the downslope of the ‘third wave’.

Often in an experiment or scientific investigation, the observed results don’t fit the expected outcome. On such occasions, it’s wise to revisit the base assumptions and re-examine the raw data to see if we made a measurement error or a calculation error.

Rather helpfully, last week the NHS did release some information in relation to the numbers of patients in hospital ‘with Covid’. Regular readers may recall I wrote about it. In essence, the revelation was that the NHS numbers in Graph Two consistently over-estimate the numbers of patients with acute Covid illness by about 25%.

The NHS were only able to provide data back to June 18th, 2021, but their clarification cleared up a point that had been bothering me since I wrote an analysis of a large data set published in the Lancet looking at Covid inpatients between January and August 2020. The analysis showed that 25% of the patients recorded as Covid positive last year did not require oxygen in hospital. I thought that very odd but maybe the explanation is that the NHS has been overestimating the numbers of acute Covid patients by about a quarter since the pandemic began. There may be other explanations, but the numbers are remarkably consistent. If anything, the corrected raw data suggests we have a lower burden of Covid related disease than we thought a few weeks ago.

This brings me to my next point – the absent signal. When a predicted signal fails to show up, we need to ask why. Did we miss it? Were we looking in the wrong place? Or were our assumptions wrong in the first place?

As the numbers don’t support the imminent catastrophe hypothesis, I expected to see a signal from the ‘health experts’ revising their predictions and explaining the experimental error which led them to frame an incorrect hypothesis. So far, I haven’t seen that signal – admittedly I don’t watch TV so could have been looking in the wrong place. I did notice Professor Ferguson predicting 100,000 cases per day (by which he meant positive tests on largely asymptomatic people) by the end of July. Oddly a couple of days later he was back on the airwaves commenting that the pandemic was over. These statements seem to me to be contradictory – yet there was no explanation as to how he came to the 100,000 figure, nor as to what had changed to make him revise his assessment so rapidly.

Readers may think I’m being flippant and overly critical of our public health scientists, but this is an important point. In medical science, the ability to critically assess information and admit errors is very important. Dogmatic adherence to a particular belief in the face of evidence to the contrary can be dangerous as it compounds error and makes repeated mistakes more likely. Given the hugely significant consequences of the advice given by Ferguson and his confederates in SAGE and the confidence with which they make predictions which turn out to be incorrect, this absent signal is crucially significant.

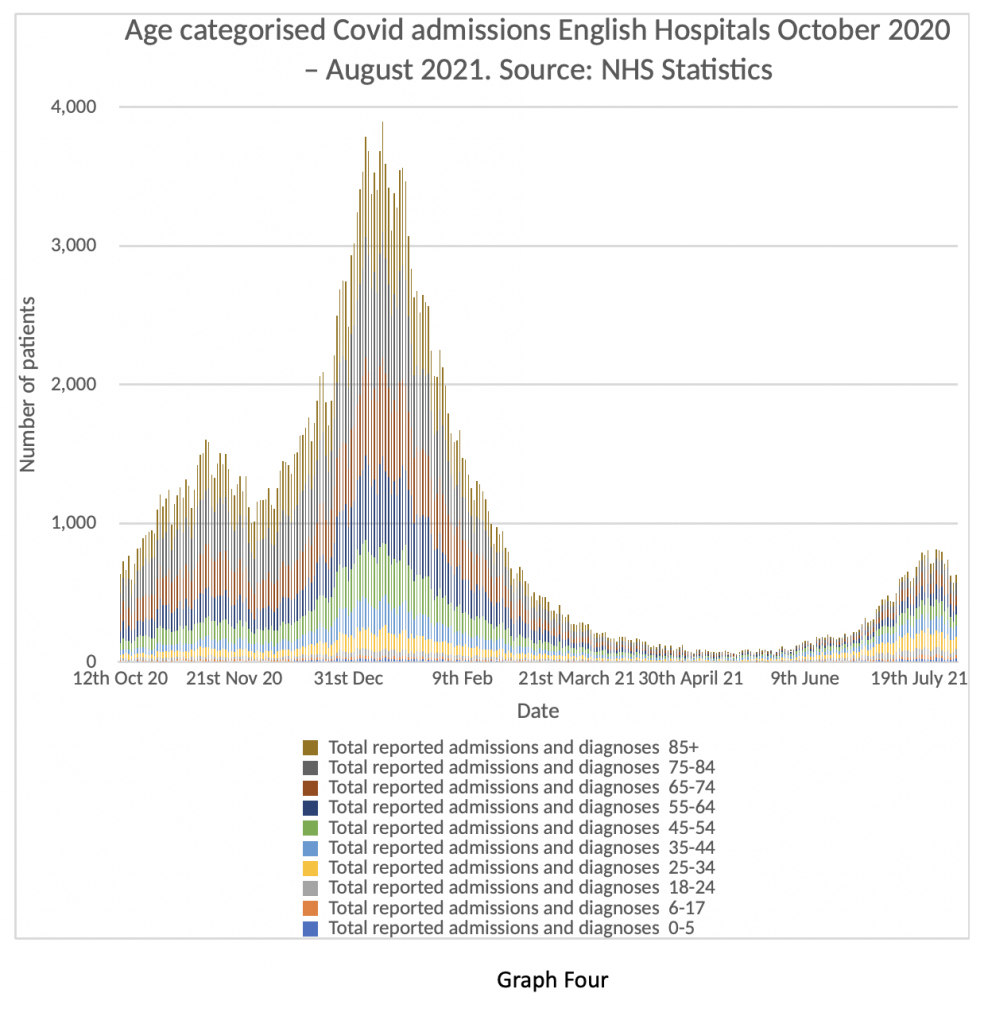

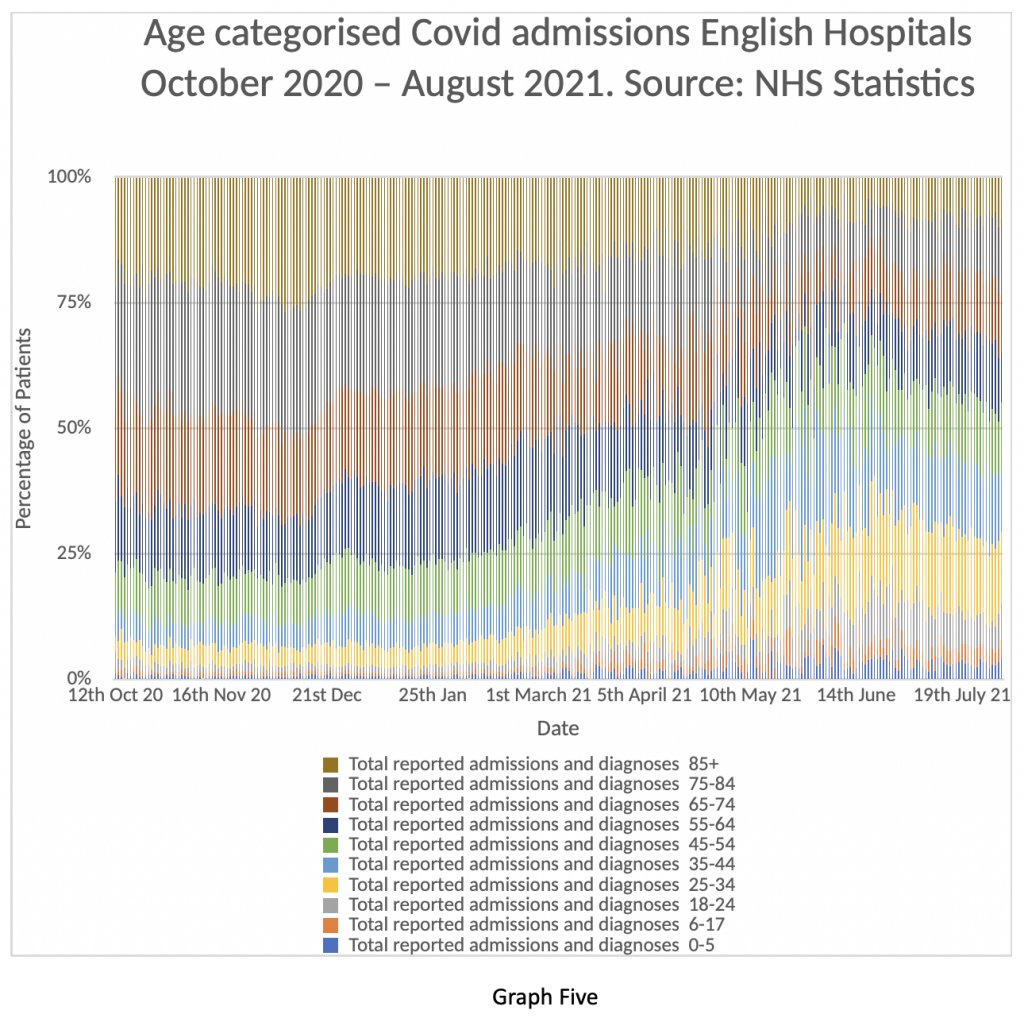

While on the subject of data interpretation and presentation, I noticed the new NHS Chief Amanda Pritchard was on the media round speaking of the high percentage of younger people currently in hospital with Covid – her key point being that people aged 18-34 made up 20% of admissions compared to five per cent in January. For some reason, she forgot to put her remarks in context – Graph Four and Graph Five provide that context.

Graph Four shows a clustered column of daily admissions by age. Readers can clearly see overall admissions running at just over 600 a day compared to over 3,500 in mid-January and that the slope of the curve on the right-hand side is downwards.

Graph Five shows the percentage breakdown of admissions by age. Clearly, the percentage of younger people has increased as a proportion of the total, but this is because the numbers of older people admitted for Covid has collapsed. There are no greater numbers of younger people being admitted per day than there were in January, but far fewer older people. Hence the relative percentage of younger people has risen as the overall total has fallen.

Why does this matter? The NHS argue that Covid still presents hazards to younger people and that selective presentation of statistics and the use of frightening adverts in the press are a justifiable way of persuasion. It is a classic ‘ends justifies the means’ argument. I thought medicine had left this paternalistic (or should I say ‘nannying’) mindset a long time ago – but as with many things, I find I’m mistaken. There is a reasonable argument to be made for Covid vaccination in young adults – but I don’t think selective use of data is a sensible way to make it, because eventually, it damages trust in important civic institutions. In one of my first posts on the Lockdown Sceptics website, over a year ago, I commented on the tendency of the NHS to misuse or ‘manage’ the presentation of data. I think that concern has been borne out over the last 12 months.

The Government may take the view that we have no time for such philosophical niceties as we remain in the midst of a crisis. I think the numbers refute this, and that trust is fundamental to the functions of a democratic society. To return to Kierkegaard: “There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn’t true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true.”

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Surely sceptics can now state with a degree of confidence that the vaccination campaign here in the UK was really a test of compliance.

The compliant were therefore subjected to two experiments; one to guage their level of compliance to authority; the second to test the efficacy of experimental drugs.

A scandal, but one I suspect most will be keen to overlook.

And maybe that is why there is no incandescent outrage at what has been done to them/us.. I find it hard to understand why I seem to be the only person I actually know, who feels like this.

I think it is becoming increasingly clear that the freedom and liberalism of the last 50 or so years has been an exceptional blip in the otherwise long arc of history of humans being trampled by power and authority and quietly putting up with it.

Exactly so. I listened to an Israeli journalist talking about this very thing back in 2020, and my heart sank, with the realisation that it was true.

Yes, we are a rare breed, but I do know a few people who didn’t roll over, despite the blatantly unscientific nonsense being spouted by government and media 24/7. That being said, all of my elderly long time and so called clever friends couldn’t bare their arms fast enough for their dose of poison. Stupid is as stupid does.

I’ve shown Government data to vaxxed friends that clearly shows that the vaxxed are:

Not one has ever shown the vaguest interest.

We have a legal and moral responsibility to devastatingly, and According To Law with correct judicial process, annihilate the perpetrators and principal collaborators of the covid policy assault against humanity, if they are found guilty of Crimes Against Humanity.

This is also what I’ve believed for a long time – that it was a test of compliance and of more broader social behaviour e.g. how easily subgroups can be stigmatised and to what extremes the ‘in-group’ would go in their discrimination. The findings were terrifying.

No.. it’s simply depopulation, having scared the public with the non virus.. I explain. .

There’s NO virus.. just a lab made spike protein.

The Identity of the Virus: Health/ Science Institutions Worldwide “Have No Record” of SARS-COV-2 Isolation/Purification. Dr. Christine Massey, Dec. 2021.

US lawyer Dr Francis Boyle, who has drafted Bio-Warfare Regs. has evidence that Harvard U Chem. Dept. Dr. Charles Lieber & Oz. Health Dept aided Wuhan Labs in the project to create the bio-weapon spike protein, in which, cancer, hap. and HIV codes are embedded.

A fake test was used to create a Scare-scam-demic.

Dr. Kary Mullis, inventor of the PCR test stated that his test only idents strands of DNA from Hep. and various Flus, and that the test was NEVER intended to be used as a diagnostic tool.

US Dr. Elisabeth Eads studies noted that the PCR test gives 97% false positives. The quick antigen test gives a 40% false negative! (Danish Manufacturer). 3 rapid test kits have Sodium azide, a chemical is found in herbicides and, pest control agents,

NOTE!! The WHO on Jan. 20, 2021 in their Directive #202005 stated that the PCR test is of NO VALUE.. this superseding their Jan.20.2020 advice to do PCR test.

I’m not sure I believe there are 2 experiments going on. For it to be a test of the efficacy of experimental drugs, someone would need to be gathering data rather than simply injecting everyone. It doesn’t seem that the necessary data are being collected, at least in this country. I think it’s more likely that the organisations behind the injection campaign really don’t care about the efficacy of their jabs. Or, perhaps, they have decided that the jabs work, and nothing’s going to change their minds.

They only care about how much money they get: the Covid vaccines were the single most profitable drug launch in the history of medicine. It is obscene how much Pfizer and Moderna made. I truly hope they are both bankrupted and have their licenses to sell pharmaceutical products revoked forever.

Efficacy.. HOW would an in..ction laced with graphene, AIDS, hep, cancer, parasites and nanobots have ANY efficacy.. when some DIE from massive clots ON INJECTION?

I assume that the establishment response will be that this study does not confirm to establishment findings, so it is therefore suspect.

Followed by its swift withdrawal on the grounds of unspecified grammatical errors….

Last week they were promoting the vaccination bus visiting schools for twelves and over. How can that, in all conscience and given the known data, be considered ethical and moral!

I thought they weren’t visiting Schools, just parents given the location of their local vaccination centre. It seems I was wrong. That is, unfortunately, a way to get the numbers up.

The Establishment only accepts ‘truth’ – which they supply – not independent fact aka mis/disinformation.

And when Mark Steyn uses the governments own stats to show how useless the ‘vaccines’ are, they’re taken off youtube. I looked at his whole show that is around one hour, that segment is missing.

It’s still there (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a8kdH2Xgf-k from 9:45), as I sent it to a triple vaccinated friend. Needless to say, I received no reply – his head is still firmly buried in the sand.

This, and more, was predicted from the outset i.e. late-2020, when the jabs became reality.

So for 18 months now, the authorities have been pushing multiple shots of drugs that they knew were, at best totally experimental, and at worst downright harmful – and of course, sold to us on the utterly false twin-premise……

……..’take this/these and you won’t die, and you can’t pass it on, oh, and by the way anyone who doesn’t is to be made a pariah’.

I have watched on, defiantly unjabbed, and wondered whether or not I was being subjected to some kind of intelligence test.

Gullability test is probably more accurate.

And they are still pushing them. Still the same wording used universally; vaccines are still the best way to protect you and your family.

Gullible is believing influenza completely disappeared in 2020, or that a novel virus was responsible for existing illnesses and the side effects of a new gene therapy intended to protect from the alleged virus.

At least in Poland they’re seeing sense I hear, because they had rejected further shots from the EU.

‘Trust me’, said Himmler. ‘I’m just a nice guy who just wants what’s best for the German people’.

Not an intelligence test, a stupid test.

Intelligence is no immunity to stupid.

I am beginning to think there is an inverse relationship; higher the IQ the more stupid.

IQ only tests spatial awareness on paper and a bit of verbal reasoning and logic. It’s an entirely useless test of intelligence in general life.

Still amazing how so many people have blithely allowed this mRNA stuff into their bodies without even thinking. And for what? Originally it was ‘safe and effective’ and would stop covid in its tracks. Then the goalposts were moved when it became evident that it didn’t. Then the mantra became ‘prevents hospitalisation and death’ – as if this could ever be proved one way or another.

Now it is quite clear that the ‘vaccine’ is pretty useless and potentially dangerous and we still really have no long term study of the after effects.

But there are plenty of jurisdictions still pretending that vaxxing makes a difference when all recent evidence is to the contrary. For ultimate looniness look at West Australia and the bars who insist on stamping your wrist with ‘vaxxed’ on entry, or the Toronto Zoo injecting some animals with some sort of covid preventative. I never knew there were so many fools in this world

That’s the real worry, the lack of thought. I expect politicians and corporations to be sinister, to erode our freedoms. But I was astonished at the total lack of thought in ordinary people.

When they began rolling out the injections for people in their 30s and 40s I watched as every single workmate just accepted it. Their only comments were related to booking appointments and feeling rough. Zero analysis on what was being injected. Many had no idea which concoction they had received, Pfizer or AstraZeneca etc. Astonishing.

This has been the weirdest. I work with those that specialise in pharmaceutical investing. Their actual job is to look at clinical data and evaluate it, and invest LOTS of money on the back of it. They are meant to be critical thinkers.

They all took the bloody jabs, even those who knew they didn’t need them (“to travel”). I’ve never held back from sharing that I am unvaccinated – my initial concerns focused on the ADE risk (which I do not think we can dismiss yet, btw), and obviously now I know about the codon optimisation that was done, on the mRNA itself, and the pathogenic nature of the spike protein produced, about all the other harms we are seeing.

Some of them definitely know they have made a mistake and don’t want to discuss it. Some are justifying it on the basis that they thought they were being a good person (“I did it to protect granny”….even though there has never been any evidence ever to suggest this would be the case, even from the animal studies when the monkeys still caught it).

It just goes to show: when investing to make money, it’s not enough to be correct – you need to understand the stupidity and psychology of all those that are wrong too, as they make the market. I do think there is a tipping point though – coming soon – where it will all come crashing down. By soon I mean by end of year.

Yes. A mass society-wide crash/earthquake and/or critical stage of “rot”/decay in which almost everything no longer works properly or at all.

Good comment, I have some similar professional experience. A friend of mine just stated ‘I trust these guys’.

He and practically all of my (former) friends are of similar mindsets, educations and large Co employment.

I think they are the foot soldiers and useful idiots of Sheldon Wolin’s ‘inverted totalitarianism’ we are now living in and under, which also rhymes with Eugyppius’ take on the bureaucracy and its people, and more.

https://multipolar-magazin.de/artikel/sheldon-wolins-umgekehrter-totalitarismus

I became sceptical on the goo on the back of the treatment of lockdown and PCR test dissent, with Clemens Arvay’s preliminary trial result comments and his treatment setting off the alarm bells, reinforced by the AZ dosage by chance ‘discovery’ and then with Doshi’s and Rappaport’s initial review of the final trial results confirming my scepticism and the sheer lack of necessity of it ringing them even louder.

When the vaccinators then also quickly resorted to offering donuts and bratwurst as incentives, I (and even my 82 year old otherwise pretty uninformed MIL) knew officially and for sure that they were lemons and that the vaccinators now knew that they were lemons too.

The rest, the AZ recall, studies, coercion, discrimination, side-effect censorship etc. is history.

I realised early that I couldn’t work in large plcs as critical thinking and rocking the boat is most definitely not desired amongst the sweaty employment masses.

Critical thinking is found in small organisations, before power politics takes over.

Big organisations in the private sector are driven solely by money, no questions asked.

I hope you are right – I said to a friend last May that I thought the injections would be stopped “by this time next year” (which currently leaves three weeks). Jessica Rose says a year from now. There’s no way I’m going to be right, and another years seems a long time, so I hope yours is the right estimate.

Quite. I never realised that there were so many altruistic people. I did it to protect others. Lol.

No you bloody well didn’t, you got jabbed because you thought you were protecting yourself.

What was it, around 10% thought they would die unless jabbed.

Project fear in a nutshell.

In a sane world Mrna would never have even been considered.

But, we live in Clown World, so papers like this are deliberately ignored, AND we still encourage kids to be jabbed..

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027869152200206X?via%3Dihub

Same with the masks, doing it to protect you, and many still doing it, bless them/as if.

I’m sure some think it protects them, more likely believe that everyone else believes it protects others and they are too weak to ignore the obvious social pressure/behavioural psychology blackmail.

Another attack by these totalitarian jabbers like Carol Malone on GB News would say….”We were scared, but we still took the jab and you are selfish for not taking part”…..Not realising the fact that they volunteered themselves.

I think that a shockingly high percentage of people actually did it to virtue signal. They knew nothing about the vaccine’s safety, didn’t even think about it. They just saw the way the political wind was blowing and gave a societal BJ to their masters.

I hope you’re right, Sophie.

Are your views just wishful thinking, or do you have reasons that suggest to you that a tipping point has been reached and that the whole facade will tumble this year? If the latter – please share – as I need something to feel optimistic about!

It is a sense, born of the number of people (and here I mean pharma sector specialists) who have said to me (over the past 2 weeks:

Once the investors know how bad the vaccines are, and start to talk about it (and they are), it will become socially acceptable to say they are bad – which it was not, even end of last year. Then they will challenge management of Pfizer and Moderna on it (read the quarterly call transcripts – they are starting to gingerly question things), and then the management defence of the vaccines will be public (and weak). Analysts tend to be a bit chicken shit as they don’t want to piss management off and lose access, but one of the more maverick ones will have a pop. And then it will become a feeding frenzy. I have seen this many times – markets suddenly swing when herd opinion shifts.

It will be out, it will be public, and people will be able to discuss it. And then it will all collapse.

Oh and I got someone who works with the previous head of vaccine development at Pfizer (who was there through the COVID vaccine studies) to get him to have a look at the Seneff paper and explain why we shouldn’t be worried. Waiting to hear what he says.

Next I’m going to ask about the rat bio distribution “study” that came out through the FOIA request and ask whether he thought that was sufficient to give confidence in the safety profile of these compounds for mass human use.

Thank you Sophie – very enlightening and you’ve definitely made my day!

Sorry to burst your bubble but no day of reckoning coming. It would be in no one’s interest & people don’t want to know. I doubt the consequences of taking the vaxx are going to worsen it was just never necessary, another pointless action with a huge cost.

There is a genuine need for optimistic investors in pharmaceuticals, because so many candidate drugs fail before launch that you need to be able to roll with the punches a lot.

Unfortunately, that can lead to some becoming less than rigorous in their evaluations prior to investments. They invest with their hearts, not their brains sometimes.

In this case, it is far more likely that they invested with their political hats on….

I have an 80 year old acquaintance who recently had her 4th jab and was moaning about how ill she felt, having been in fine fettle beforehand. Madness. But if you say anything, YOU’RE the mad one!

I had a young lad in my workplace who had both jabs. The second one made him very ruff and had a few days off work. I did try to warn him about not having the second. He had the first before we met. He did say after, that is it, fuck this I’m not taking another. He only had it because he didn’t want to pass Covid to his Grandmother. That and going to a club was a common reason.

That’s because you’ve never been a teacher.

There is still a vastly widespread, zombie-like belief in the overall good intentions and trustworthiness of those in government, and in the infallibility of anyone with a degree to their name and the label of “expert” around their neck. It seems to matter not one jot how often people are brazenly lied to, let down, gaslighted, insulted, robbed and physically damaged by those in power. They keep coming back for more. Like those wibbly wobbly toys that always bounce back with an idiotic grin on their faces, no matter how many times you knock them down.

Just wait until the next election, and watch the millions of votes pile up once again for the same old LibLabCon gangster conglomerates who are all pushing the same destructive groupthink agenda. All fanatics for Zero Covid, Zero Carbon, Zero freedom and a Zero economy. The only difference between them is the colour of their rosettes.

I believe there is something in the jabs that kills of certain braincells, particularly the ones that involve critical thinking.

Yes, I was thinking about Trump the other day. To me he is definitely the lesser of the two evils but while he talked of the ‘Deep State’, he didn’t seem to do much about it when the subject of Julian Assange came up, and that was after saying how he “loved Wikileaks”.

Never underestimate stupid – it is the default.

and selfish.

I do wonder how many of those poor animals will die because of the vaccine. I seem to remember reading that using it experimentally in animals killed them all.

And who,on earth cares if a hippo gets covid anyway? Why does it matter?

If it’s an 85 year old hippo (or whatever the equivalent is in hippo years), nobody should care. From an evolutionary perspective it is irrelevant. Similar for humans.

The only positive things Romans have given us is concrete,plumbing and western law.

To prove fraud

Common Law dating back to Cicerone

PUNTO UNO;

MATERIALLY FALSE STAEMENTS

or purposeful failure to state or release material facts which non disclosure makes other statement misleading.

PUNTO DUE;

The false statements is made to induce plaintiff to act

PUNTO TRE;

the plaintiff relied upon the false statements and injury resulted from the reliance on.

INdisputable facts that no judge in any western nation can refute hence empirical data alone will be its down fall regardless of EUA> Hence Statum dictum does not equte to favtum dictum just by statute alone Cicerone established this little historical tid bit .

but idigress Fruad prinicple alone will determine PCR test and the new therapeutics. Swine flu epidemic of 2008 alone will undue the massive lies.

There’s a sucker born every minute

On reflection I’m coming to the conclusion that the mass imprisonment (some call it lockdown) was not a bad thing

The real question in my opinion is why the ever so pig shit thick were allowed to wander around unsupervised in the first place

Once mass imprisonment had been achieved it should not have been rescinded

As I encounter them on my wanders I have an overwhelming feeling of contempt

That’s a little harsh. Plus I don’t want to be locked down.

It’s OK. We can identify and segregate the stupid by the bit of cloth they have stuck to their faces, and imprison them as appropriate

“The real question in my opinion is why the ever so pig shit thick were allowed to wander around unsupervised in the first place”

A very fair comment Cecil.

The problem is all the politicians, all the media and the entire medical establishment with a tiny amount of exceptions have been aggressive cheerleaders for these jabs.

So they will close ranks and help each other cover up or wave away their crime.

And it will be easy for them because the majority of the population took the poison and don’t want to hear how they were mistreated.

The badly affected will still be a relatively small number and will have to suffer in silence. Most likely they too will live in denial.

Correct. Very few who either enthusiastically or meekly accepted the medical experiment question it, or even WANT to know that they aren’t as safe as they were told.

An Iceberg comes to mind, much more below the surface that we don’t yet know.

When they all start getting dementia in a few years time, things will be interesting.

What do we, the unscathed, do then? It’s bad enough being surrounded by sheep people. When they become demented sheep people, society will collapse.

(I’ve been scaring myself silly with the Seneff paper on G quadraplexes)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihwoIlxHI3Q&t=0s

Scary???

Sheep people are easier to control. People always say when referring to the WEF, WHO, EU, etc…Totalitarian Empires always crumble because of the human desire for freedom etc. Problem is, they didn’t have all this technology before. Who is to say the next drugs will keep people in a state of compliance.

“I’ve been scaring myself silly with the Seneff paper on G quadraplexes)”

Good job this stuff goes right over my head.

Experimental concoctions paid to governments for the use of their populations? Unlike individual paid volunteers. Its called a Windfall.

I can’t help thinking Shane Warne’s death was caused by the vax.

Too many people with too much to lose for any transparency.

For now, yes. Until the children start dying.

When a man loses his kids he has nothing else to lose. I wouldn’t want to be one of the main players then.

Not that many kids have been vaxxed though. In this country anyway.

I think if people pushed their children to get vaxxed, they will largely be in denial that they chose to harm them. It’s not like they can deny they weren’t warned. Anyone half awake knows there are issues. I think the parents will commit suicide instead of go insane with rage, for the most part.

If you have to bump yourself off, at least take one of these scumbag Ministers with you.

In the overall scheme of things the numbers are small. So it will still be the case that the vast majority will be fine.

The problem is that the pharma establishment have succeeded in lowering the bar enormously when it comes to drug and vaccine safety.

Previously a handful of serious adverse reactions were enough to stop a drug or vaccine. Now so long as the vast majority are ok, it seems to be fine. They’ve established a new norm.

In fact it’s worse than that. They’ve flipped it around so that to report any adverse events or make a big deal out of them is now considered putting people’s lives at risk because on the whole – they tell us – jabs work and save lives so to create doubt in people’s minds is equivalent to killing people.

That is the truly revolting state of things.

He who loses a child will just have to suck it up.

Yes!! Exactly this!! This is what I’m worried about. People have been conditioned to find it acceptable to have a novel, chemical concoction that has undergone very limited and short-term testing to be pumped into their bodies, in many cases subject to coercion of varying degrees, all for “the greater good”.

When it became apparent that it did not work as promised, they told outright lies saying they had never promised precisely what they had indeed promised. Then they pushed for people to inject even more of the same product that had clearly already failed, and a great number went ahead without question and did so – all the while continuing to wear masks, distancing, quarantining – literally saying by their own actions that they did not themselves believe the sludge worked. And still they think these actions were okay, still they are willing to accept more of the same if come the autumn they are ‘requested’ to get more of the sludge.

The thing to start asking these people is, will they find it acceptable that any time some virus (old or new) is doing the rounds, if the authorities tell them they must take an injection, do they believe that they are obliged to do, even if this were to mean getting a different shot literally every week/month, even if they just kept getting sicker and sicker. Force them to think, make them realise where their abdication of responsibility for their own bodies can lead to. Make them feel uncomfortable.

This study seems bogus and lacks credibility when it can’t make sums add up in the tables, it clearly wasn’t peer reviewed as the mistakes would have been fixed.

detractors will likely point to it as a failed study and use it to deride those who are against the cv vaccines (no not anti vax, just anti covid vax (I’m more anti mRNA than anything else)).

it looks more like ammunition against the “anti cv vax” narrative.

Yes, it’s not impressive or reassuring if basic essential numbers aren’t consistent. And as Will says all the modelling and adjustments involved don’t help either. I’m not going to share it with anyone.

I’d say that the problem is with the pier review process

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/281528

If the reviewers had done their jobs properly there wouldn’t be a problem.

I can do pier reviews….. Llandudno is excellent – there you go.

I remember quite clearly that the Israelis flagged up the risk of myocarditis in February 2021 because I have two adult sons (late 20s/early 30s) and I forwarded the article to them. That was long before they were “offered” the jab. One remains unjabbed, the other had two shots because he travels abroad extensively. He now accepts that they are not safe and I hope and pray he has no more.

In may family no-one talks about the consequences of being jabbed. Yet in the last year my sister, her husband, my father and mother in law all now have high blood pressure. My sister in law in constant discomfort, her husband had open heart surgery. My niece couldn’t walk for a week. Another nieces husband has tinnitus. My brother had shingles.

Only the niece who couldn’t walk after first jab blamed it on the jabs.

Most of my family all had COVID symptoms even though jabbed multiple times.

I doubt any of them would consider yellow card as it might all be a coincidence.

I don’t speak to them about it. Not being jabbed myself has caused some upset. Though I remain in remarkably good health.

Not being able to walk is hard to blame on something else, unless you have MS or something.

I have a humdinger of a cold. How did that happen with all this covid flying about.

After bragging how well I had been, cold and flu free, I came down with a heavy cold which kept me in bed for a day and a half but I bounced back very quickly. I expect had I been tested it would have been positive for covid.

The fact you remain in good health and unvaxxed must irritate them.

“My niece couldn’t walk for a week.” Bloody hell, is she alright now?

I’m 67, unvaxxed, just had Covid, it was a total nothing-burger. I barely noticed I was sick. Didn’t stop me doing anything. No normal healthy person needed these ridiculous clot shots.

How did you know you had covid?

Absolutely Chris, I’ve had the main covid virus and two of the variants and with the exception of the main one back in Feb 2020 which felt like seasonal flu the other two just felt like a mild cold for a day or two. I’ve never seeked medical help because I never felt that my life was in any danger as when catching a normal cold/flu during the pre-covid years. Unless you were very frail and elderly and/or with serious underlying health issues then there really was no reason to have a single jab nevermind three jabs and now a fourth.

Is this the survival rate of those who had covid, or is it a calculation of the entire populations of the respective countries including those who didn’t catch covid?

I’m 66, unvaccinated, and had covid in December/January. I was sick, and it wasn’t pleasant, but nowhere near as bad as when I had flu. I didn’t get tested as I knew what it was and precisely who I caught it from, who was confirmed to have had Omicron.

MOH, 70, unvaccinated, who caught covid at the same time from the same person, was very ill and ended up in hospital for a week.

It affects everyone slightly differently depending on existing health conditions, age, and sex. I wouldn’t say it was a nothingburger, but we’re both still glad we remained unvaccinated.

HCQ or Ivermectin with Vit D3 might’ve helped things clear up faster, if only it was available in Boots in the UK. Wonder why not!

I genuinely do not think I’ve had it, they should study me for science.

I never sanitise, don’t mask, only work from home when forced to, have a terrible diet and smoke sometimes. I mean it’s genuinely puzzling. Unless I was one of those “asymptomatic” “sick” people?!

You probably just have an immune system ‘to die for’ (or not, as it turns out).

UKHSA data shows triple jabbed are more likely to ‘test positive, be hospitalised and die ‘with covid’ than the non/single/double jabbed combined.

The fake vaccines are the bio-weapon, there was never a pandemic causing virus.

Pity they hadn’t done this work BEFORE injecting half the planet with these drugs. Y’know, like they have with every drug since Thalidomide.

Informed consent would have been desirable, not Oops.

‘Y’know, like they have with every drug since Thalidomide.’

That would be an assumption on your part.

It turns out that for vaccines long term safety trials never take place, indeed the two month long initial phase three trail for the covid vaccines was an extraordinaril long safety trial for a vaccine.

The fact that vaccines as a matter of course go through ridiculously short safety tests is one of the main objections raised by those labelled ‘anti-vaxxer’.

This vaccine disaster has had the effect of making me look sideways at all vaccinations that are routinely offered. I am coming to the age now where it will be suggested I take one for pneumonia and one for shingles (although I’ve had shingles, so I don’t know how that works). I will not be taking them. My trust has gone completely. This was not an intended consequence, but there must be a great many people who now feel like this.

I am inclined to agree. I’ve looked at the data and the shingles one is pretty good, but I still think, after the past year, actually you can take your vaccines and ram them all up your arse. It’s a purely emotional response, but I feel I am owed one after 2 years of shit.

Once basic trust is gone, it’s difficult to work out which bits you can and can’t trust them on.

Nowadays, I wouldn’t put it past them to combine the standard annual flu jab with some mRNA gloop and hope you didn’t notice.

I wonder if the continued enthusiasm for jabbing, even though the current strain is the mildest yet, is because governments have committed to buying x million shots and don’t want to have warehouses full of unused vials.

I heard they are thinking of combining the flu jab with the covid jab so be aware of that.

And we may have another ‘Thalidomide’ but many multiples worse.

The clinical testing was done on millions of people worldwide. Obama said that publicly.

Everyone I know that has been jabbed seem to be engaged in endless rounds of infection. Two/three weeks clear then another two weeks of colds/chest infections etc

One of these perpetually infected commented the other day that we had been very lucky. It was pointless telling her we had not been jabbed

In one group of six men in the pub five have died in the past six months. The survivor who is a rabid covidian says he doesn’t understand it. My mate (a fellow sceptic) and I exchange knowing glances every time the survivor speaks

My Dad is 75 and decided that taking the jab was reckless.

All his golf buddies are jabbed, since then one has had a stroke, two have been diagnosed with cancer, one other jabber appers to be well.

My dad had the shits last Thursday (he went out for a curry) apart form that he is fine.

My friend’s ex PE teacher father dropped dead, HA on the golf course – I wouldn’t ask but considering how well to-do they are and that she works for the NHS I think it’s safe to assume he was tripped stabbed.

I guess we should just consider ourselves lucky at this point that the leaky jab experiment didn’t produce something much worse than covid and deadly to all.

Don’t keep quiet. Say what you think, and say that you’re unvaccinated and haven’t been constantly ill. It’s time to throw back some of the bullying that we’ve all been subjected to.

Agree – we HAVE to make it socially acceptable to say the vaccines are not good. The truth will never come out otherwise.

By spooky coincidence: “AstraZeneca/Moderna’s mRNA treatment for heart failure looks promisingThe therapy – an mRNA-encoding vascular endothelial growth factor – looks promising for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery”

Hmmm… so mRNA jungle-juice can act on vascular cell function. So is it too much of a stretch to imagine they were aware that the mRNA Granny-protector-juice might have an untoward effect on tissue cells?

What better than a Human trial involving hundreds of Guinea-pigs across all ages to observe this – and without the need for complex and hugely expensive ethical and regulatory work-up, and at the same time raking in huge revenues and profits with zero liability.

Now, I don’t want anyone to think I am being cynical.

I meant hundreds of million.

‘The authors conclude the risks “should be balanced against the benefits of protecting against severe COVID-19 disease”.’

I suppose they have to say that to keep the Truth Gestapo off their backs, but the increasing volume of hard data shows the pseudo-vaccines are actually increasing the risk of infection, severe disease and death with rates much higher than in the unvaccinated, and worse, seemingly accumulative – the more doses the higher the risk.

it is clear the pseudo-vaccines are damaging immune systems, the questions are, is it short term or long term; is it just muting the response to CoV 2 or other pathogens?

It’s an absolute horrow show:

(my bold)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027869152200206X

Nothing to see here. There’s a war on, don’t you know!

This is beyond scandalous. It is unforgivable. This is nothing short of an indictment of the rush to pump out an unproven novel biological technology. Heads should roll for this. A good argument can be made that the phrase ‘heads should roll’ ought to be interpreted in a literal fashion.

You’ll like this then

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BzEigubrO5A

“Spike Protein Spills in the Blood of the Vaccinated Individuals (Study)”

Thanks. I’ll watch it later.

I remember when that came out last year (in pre print), it was pooh-poohed by the mainstream as “too small a study to be relevant”

Of course it’s bloody relevant! They should have done all this work before it was rolled out!

I’m watching it now. 25 minutes in. Words fail me, my friend.

Was granny saved, thats the important thing?

And can you look her in the eyes and say you weren’t “vaccinated” (bullied, coerced into having it).

You’ll need something stronger than Pfizer to save mine.

Can someone tweet this article to JHB and ask her how she feels about relentlessly banging the jab drum for months on end on her show, and if the money was worth it?

The only – the only – thing I can say in her defence is that she has repeatedly said she doesn’t believe children and teenagers need the vaccine. But otherwise she’s gone along with the government narrative. And she’s had covid twice now.

Was she in on the coercion though. I have no problem with people who support personal choice?

A cynical person might suggest our inept government have been investing our taxes in a pharmaceutical ponzi scheme. So far the only return has been the opposite of improved health. ‘Gamblers Anonymous’ might be worth a call!

The film Equilibrium 2003 is a perfect example of this collectivist madness and where it can lead.

These kind of articles by Will Jones are invaluable, just a shame they don’t get the MSM asking questions.

I was talking to a mate today. He likes walking and running. Only just in his 40’s. I said “You’re finding walking and running hard aren’t you? You feel like your heart is overloading”. I haven’t seen him in the flesh for 2 years but we talk a fair bit. I asked “How do I know that?” and posted this article.

So many people fell for the “It’s perfectly safe even though we cooked it up in a weekend”. Some day these people have to be made to pay for what they have done. Will there be enough people left to make them pay?

Poland has unilaterally backed out of its contract to buy the BioNTech/Pfizer coronavirus vaccine, claiming oversupply and financial difficulties brought on by the flood of millions of migrants fleeing the Ukraine conflict, according to Health Minister Adam Niedzielski.

Niedzielski told TVN24 that the Warsaw administration had notified the European Commission and vaccine providers late last week that it was activating a force majeure clause in the procurement contract and would refuse to pay for or accept delivery of any additional doses.

The improving pandemic situation, according to Niedzielski, meant that vaccinations were no longer required. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian refugee crisis had put a strain on the government’s budget.

The government attempted to find a compromise by asking for deliveries to be staggered over a 10-year period, but “we encountered a complete lack of flexibility on the part of the producers,” he said.

https://greatgameindia.com/poland-cancel-vaccine-contract-pfizer/

‘For some reason the study did not look at the risk outside the 28-day post-vaccination window, so we don’t know whether the elevated risk continues past that period.’

I can answer that one easily: the authors will want to publish a second paper on different time frames, since publishing two papers is better than one when publishing the same material.

Careers progress by publishing hundreds of shorter papers, not five seminal ones.

The law and civic law in general is a “bitch” excuse my profanity. One thing that western so called civilisation forgets is that the so called “Romans ” have given us is concrete, plumbing and civic law. Old Latin saying ” Statum Dicues Statum Factum Stutus Dictum. In So called modern democracies let say dating back to the mother of all modern day “revoluzioni” The American Revolution to the more recent ones lets say good old Benito financed and payed by lets say financial interest Adolfo. States make laws they hide by the semblance of law because it becomes statute.

Principles of contract law 101

Required elements to prove fraud:

PUNTO UNO:

Materially false statements or purposeful failure to state or release material facts which non disclosure makes other statement misleading.

PUNTO DUE: The false statement’s is made to induce Plaintiff to act.

PUNTO TRE: The Plaintiff relied upon the false statements and injury resulted from this reliance.

Hence civic law is another kettle of fish but Romans have given us all the modern tools to bury this once and for all.

Safe and effective the percentages of efficacy that were parroted.

The mere fact that already we are cing the remnants of the Romans are the recent federal district USA court readings on g-string and jock strap laws on federal travel in the USA.

January the fed district court ruled. “The Data Dump and all the adverse reactions recorded by all the test group during the phase three trial.

Fed EX workers circa half million instantly immune from any BS MANDATE EUA therapeutic products forced upon the people via such Dictum Stutum.

Cing I live in the new EMPERO ROMANO Natostan. Roman precedent is a bitch like concrete plumbing and civic law. Those principles date bak to Cicerone.

So my fellow Natostaners thats how the cookie will crumble.

There is more because if anyone recalls the famous PCR test and the cycles threshold BS.. There is so much what i would do to be a Barrister in the dien Natostan empire.

.

Crimes Against Humanity don’t expire, and the perpetrators and principal collaborators of the covid policy assault against humanity should look forward to prosecution, in every jurisdiction.

If msm bothered to write what has really taken place with these experimental biologicals, most people would decline.

………….. it’s hard to see how it could be worth it, or why these vaccines have not already been withdrawn for younger age groups.

As we can say but the writer of the article perhaps can’t (or chooses not to): because it ain’t about health. Easy.

What do the injected expect from graphene, AIDS, hep, cancer, parasites and nanobots VERIFIED in unlabelled mRNA injections?

Oxide: A Toxic Substance in the Vial of the COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine? By Ricardo Delgado and Prof Michel Chossudovsky Global Research, January 19, 2022.

Dr. Vladimir Zelenko. The mRNA injections HAVE AIDS!

Swedish study 2.28.22 demonstrated and confirmed that the mRNA in the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid injections infiltrate cells and transcribes its message onto human DNA within 6 hours, altering our own DNA

Dr. Sucharit Bhakdi, Autopsies Prove Vax BioWeapon Caused Autoimmune Attacks And Death. (Based on 70 autopsies done by Germany’s top pathologist, Prof. Dr. Arne Burkhardt).

Austrian graphene Research Scientist/Med. Dr. Andreas Noack was MURDERED after he released his evidence of graphene in the 4 mRNA injections, and describing it as ”razor blades in the blood that will kill all who get it”.

Prof Igor Chudov Pfizer vaccine, taken once, permanently changes the DNA of affected cells…DNA transcribed from Pfizer mRNA Vaccine contains mutant gp130 Cancer Cells. 28,2,22

Journal of Hepatology. Immune-mediated hepatitis with the Moderna vaccine.. confirmed.

Brghteon. Dr. Jane Ruby Show. Incredible evidence of cancer diagnoses in the jabbed, exploding cancers in the boosted. 2.15.22.