A snapshot of data from the beginning of the month in Israel suggests that the Pfizer vaccine is not protecting against infection now the Delta variant is in town, with infections in the vaccinated across all age groups being no less than you’d expect if the vaccine did nothing.

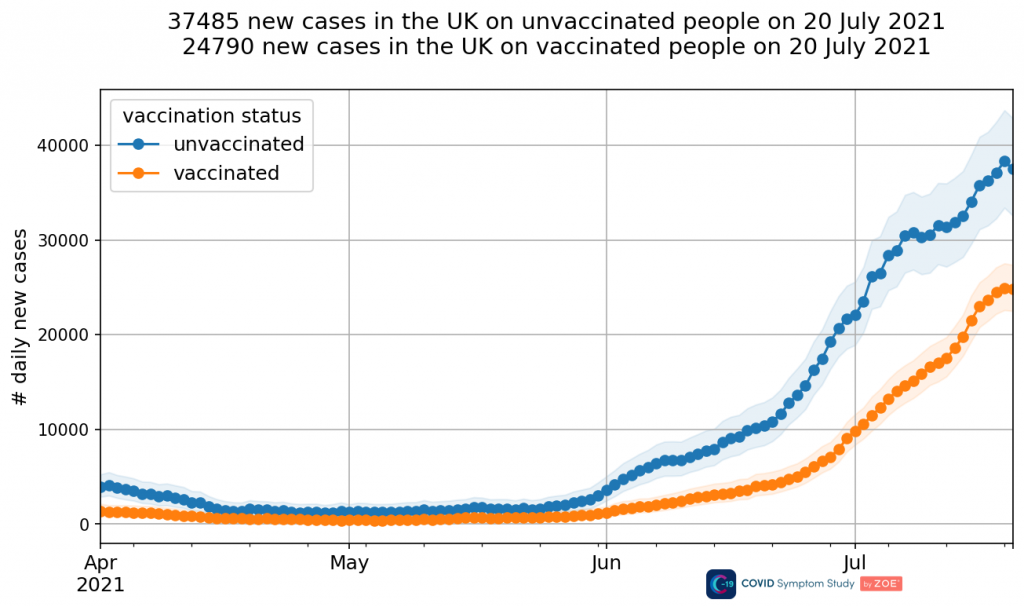

Could there be another explanation here? Possibly. It’s only a snapshot. What if infections in the unvaccinated peaked earlier than in the vaccinated, as ZOE data at one point showed happening in the U.K.?

Talking of ZOE data, in the middle of last week the study updated its methods (described here) which had the result of completely removing the peak in the unvaccinated infections and replacing it with the opposite, a further climb (see below, the old method put the peak around July 1st).

It’s hard to know what to make of such a radical change. One of the main takeaways for me is that it’s difficult to see how one can really trust ZOE data now or rely on it for anything. If it can change so radically from one day to the next, overturning the former trend, then how can it be relied on at all? If it was so wrong before, what confidence should we have that it’s correct now? It’s hard to shake the feeling that it was changed because it didn’t look right to someone, and was changed until it looked right. They even state: “We can see our updated methods align more closely to trends observed in Government confirmed cases.”

But back to Israel. New statistics from the Israeli Health Ministry are not quite so alarming as the above snapshot suggests, but they’re not far off. They suggest that the Pfizer vaccine is only 39% effective against the Delta variant, dropping to 16% for those vaccinated in January. The Times of Israel reports:

New Health Ministry statistics indicated that, on average, the Pfizer shot — the vaccine given to nearly all Israelis — is now just 39% effective against infection, while being only 41% effective in preventing symptomatic Covid. Previously, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was well over 90% effective against infection. …

The Israeli statistics also appeared to paint a picture of protection that gets weaker as months pass after vaccination, due to fading immunity. People vaccinated in January were said to have just 16% protection against infection now, while in those vaccinated in April, effectiveness was at 75%.

Doctors note that such figures may not only reflect time that has passed since vaccination, but also a bias according to which those who vaccinated early were often people with health conditions and who are more prone to infection, such as the elderly.

While it may be true that the more frail were in the earlier cohort, even so 16% is very low, frail or not, and that will be an average, with some higher than that (the less frail among the early vaccinated perhaps) and some lower still.

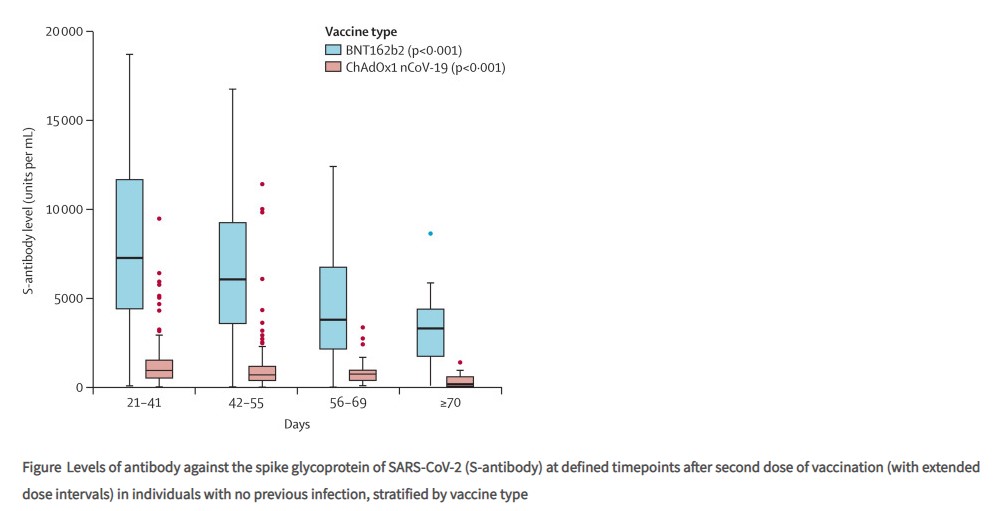

A new study in the Lancet has shown that antibodies from the vaccines notably decline over the course of three months (see below), which may support the idea of declining efficacy over time – though as the authors point out, antibody levels don’t by themselves determine real world effectiveness because “memory B-cell populations appear to be maintained”.

Some Israeli scientists are unhappy about the way the data is being used by their Government to imply that boosters and new restrictions are needed, saying the definition of serious illness has been changed and the statistics, which are dealing in small numbers, don’t take into account the different propensity of vaccinated and unvaccinated people to be tested for Covid.

Others, however, are sceptical about the efficacy of the vaccines. The modelling team at University College London is now working on the assumption that the vaccines have basically zero effectiveness against infection by the Delta variant. However, they also somewhat incongruously assume they are 85.5% effective at preventing transmission. Neither figure is supported by any obvious references so it’s not clear how seriously to take these estimates.

Meanwhile, the team at Public Health England (PHE) has had its study on vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant published in the NEJM. The pre-print estimated AstraZeneca effectiveness (two doses) against infection with the Delta variant at 59.8%, but with new data this is up to 67%. It estimates Pfizer efficacy against Delta at 88%. Why this is so different to the latest Israeli data (39%) has been a matter of some discussion. The Swiss Doctor (SPR) suggests it is because the PHE data is out of date, coming from April and May when prevalence was low. The infection rate in the unvaccinated will also be skewed upwards by the cohort being younger (younger people have higher infection rates regardless of vaccination status) and it’s unclear how fairly PHE’s adjustments have allowed for that.

Separately, it was reported last week that Australian socialite Anthony Hess, who is fully vaccinated, spread the virus to 60 people during a busy weekend in Los Angeles, most of whom were also fully vaccinated. However, Hess didn’t develop symptoms until several days later and L.A. is currently experiencing a surge so it’s not clear how it can be known that Hess was the index case for all the other infections. Nonetheless, the fact that most of those infected were fully vaccinated illustrates the lack of protection provided by vaccination.

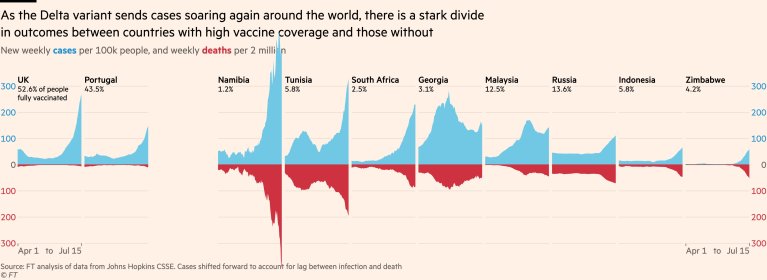

The Swiss Doctor argues that while the vaccines’ effectiveness against infection looks to be fairly weak, effectiveness against serious disease and death is more robust. This can be seen, for example, in the graphs below, where the proportion of hospitalised cases seems heavily dependent on the vaccination coverage (though a confounder may be how large earlier waves were).

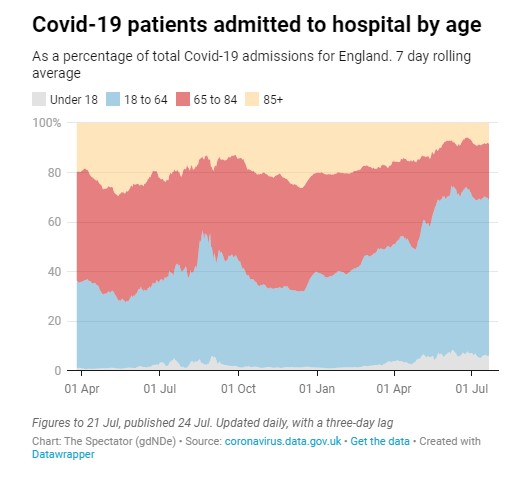

The sharp drop in the proportion of older people being hospitalised since spring in the U.K. (the 65-84 cohort’s share has dropped from 40% to 22% while the 18-64 cohort’s share has grown from 37% to 64%) is also an indicator of protection from serious disease (see below), as older people have higher vaccine coverage.

A recent piece on the Daily Sceptic suggested that evidence from the ratio of the positivity rate to the hospitalisation rate in Scotland shows the vaccines are not reducing serious illness. However, this assumes that there are no confounders in the positivity rate for the recent surge, when in fact there may be, not least the huge increase in mass lateral flow testing since March. This would depress the positivity rate (as more healthy people are being tested even though they are unlikely to have it) and so would give a false impression that the infection-to-hospitalisation ratios of the earlier surges are being matched.

The evidence is now mounting that the vaccines are not as effective at preventing infection as the trials and other early studies indicated, not least the big outbreaks in highly vaccinated countries such as Bahrain, Seychelles, Maldives and Chile. This incidence data is supported by the fact that the vaccines don’t produce mucosal IgA antibodies, which are known to be important in combatting infection in the early stages. However, the vaccines do produce IgG antibodies in the blood and also to some degree a T cell response, which may explain their apparent efficacy against serious disease and death.

Unfortunately, the growing evidence for the lack of vaccine efficacy against infection and transmission is leading many to conclude that vaccine boosters and more restrictions are needed in the face of the Delta and other variants. But this is the wrong conclusion.

The most important conclusion should be that vaccination offers little to no benefit to other people, so no one (least of all children) should be vaccinated in the wrongheaded belief they will protect others. Neither can there be any justification for coercing the population to be vaccinated through vaccine passports and the like, as vaccination is a personal choice that protects the vaccinated person only.

The fact that the vaccines appear to prevent serious disease and death should be sufficient to allow life to return to normal now that all the vulnerable are vaccinated. In truth, even if the vaccines didn’t prevent serious disease we should return to normal because there is no evidence restrictions are effective in reducing infections or deaths. And even if restrictions were effective there is no evidence they do more good than harm. And even if there was such evidence that doesn’t mean the state is entitled so egregiously to suspend the population’s liberties indefinitely to prevent the spread of a relatively mild (fatality rate under 0.1% for most of the population) contagious disease. But those are arguments for another time.

We locked down last winter to wait for a vaccine. Now we have our vaccine, we must return to normal, before lockdown becomes a way of life, and humanity becomes stunted by its own disproportionate fear of disease and death.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The snake oil doesn’t work.

I never thought it would.

Neither did they

I’m not certain that’s true. They’re hoping to make further zillions by using it to cure us of cancer and a host of other plagues, so this is a bit of a PR disaster, which no doubt they will try to fix with Further Fear.

It may turn into a PR distaster – one can only hope – but so far no-one I know seems to be bothered by the fact that they don’t appear to work too well or that they haven’t got their freedom back. They just accept things as they are.

I think for the makers and pushers of this stuff, and stuff like it, the main priority is that things appear to work, not whether they actually do or not. Same goes for all the claptrap with masks, SD, lockdowns etc.

One example – just one example – of what they do with cancer – they say that if people don’t get cancer again within an arbitrary cut-off period, they count as a recovery from their “treatment” (toxic chemotherapy efc.). And then die of cancer after this period. So they are recovered. But dead. You can bet your bottom dollar (and we have already seen plenty of evidence) that it is a right web of lies with these “vaccines”.

I think Netanyahu thought they worked – that’s why he denied them to the Palestinians.

Says a lot about Netanyahu, wrong on just about everything.

Using mRNA technology to “cure” overpopulation doesn’t mean that it couldn’t have better uses.

the crooks have been lying about cancer for decades. Sadly, many people can be persuaded to believe lies.

I agree with the amount of money poured into Cancer Research you would think they’d have found a cure, its my belief its such a good moneymaker for the pharmaceutical companies they don’t want to cure cancer.

And in just the same way I suspect the “vaccines” were only intended to have a temporary effect so they can market the endless boosters.

Covid vaccines routinely thrown in the bin as not enough people are coming forward – Once thawed, the Pfizer and Moderna shots have a maximum shelf life of up to one month in the fridge ~ (NO MENTION IN THE GATESOGRAPH ABOU THE WORLDWIDE RALLIES)

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/07/24/covid-vaccines-routinely-thrown-bin-not-enough-people-coming/

Stand in South Hill Park Bracknell every Sunday from 10am meet fellow anti lockdown freedom lovers, keep yourself sane, make new friends and have a laugh.

Join our Stand in the Park – Bracknell – Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

HOME EDUCATION – Ex-Primary School Teacher on Resistance GB YouTube Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZ5oS2ejye0

https://www.hopesussex.co.uk/our-mission

No, what doesn’t work is the naive and biased data analysis by people who have no clue. An article which explains how the Israeli data should be analyzed properly (summary: Pfizer vaccine >80% effective against severe cases in all examined age groups):

https://www.covid-datascience.com/post/israeli-data-how-can-efficacy-vs-severe-disease-be-strong-when-60-of-hospitalized-are-vaccinated

You know the line “but it stops you being hospitalised/brown bread”

That is broadly the only true thing about the vacine, it turns a negligible risk of severe disease (for most people) and a relatively small but large enough to be measurable risk of severe disease (for the vulnerable) in to a risk so small (for everyone) it is below negligible. Although the lockdown zealots all deny this fact and try to pretent covid is still a massive threat, they happily mistake inefectivness in stopping transmission for ineffecitveness in stopping severe disease.

We don’t know that is the case – it could be that the now-prevalent variant is more infections but less likely to cause serious illness. This would be in line with how viruses tend to mutate.

Added to which, many of the badly susceptible have already died, whilst many of the less susceptible probably have some acquired immunity following minor infection.

Or it could be that it’s all hype.

….they happily mistake ineffectivness in stopping transmission for ineffectiveness in stopping severe disease.

When they don’t do either.

“… now the Delta variant is in town”

FFS … stop this nostalgia for the government fables, Will.

The variant mythologies have never stood up to scrutiny.

From the start, the efficacy of the ‘vaccines’ have always been overstated – as has always been the case for many medications in general. I’m sure there are good people working for Big Pharma. But the commercial reality is that their prime corporate objective is to make money – just like Big Tobacco. The PR is about as trustworthy.

What we have is the usual process of a moderate virus becoming endemic.

Tacitly (and with ulterior motives on top), the government has admitted this inefficacy.

The ARR isn’t the top and bottom of the data – but it’s vital in assessing real world effects, and was essentially predictive of this (~1%) lack of world-shattering efficacy.

Well concluded Will, we must treate the vaccine, deployed non-coercively as the end of the pandemic, not a start of a “new normal”. Your arguments are spot on, the vacine does what it needs to, prevents serious disease in the vulnerable, it doesn’t protect others around those who’ve taken t and it doesn’t need to. The point now is how the people can enforce a return to the old normal when those in power are so willing to ignore all the facts, I think we are well beyond the point at which the lockdown zealots will buckle under the weight of reasoend debate alone.

“the vacine does what it needs to”

Oh yea of incredibly deluded faith! 🙂

I think you need to relinquish the teat.

Your arguments are spot on, the vaccine does what it needs to, prevents serious disease in the vulnerable,

So the vaccines are likely magical , because If you don’t need them, then they may kill you, out of spite, perhaps. However, if you are old and vulnerable then they take pity and do what they are supposed to do. Some might just say this is stretching a moot statistical point into the realms of absurdity.

Others might more realistically say, that the vaccines don’t work, because they were never meant to and that their real job is to cull the herd. Then the great unknown would be the extent of the cull. But lucky for us, boosters will be on the way and no doubt, they will be even more magical, so not too bad then.

Well, yes, to cull the herd, but also of course to make a packet of money from tax-payers (now and in the future).

Yes, as a side effect the Covid scam is making a packet of money for some people. Essentially though, it’s just the long dreamed of and long planned cull of the masses, that has beguiled certain sections of the global elite, for a century or more.

Its pretty obvious now why politicians want everyone jabbed – they don’t want the unvaccinated to be factored into the stats and make the Vax look bad. Same dynamic as countries not following lockdowns. It embarrasses the narrative and makes them look foolish. They want everyone on a level playing field so Vax v unvax doesn’t exist

They don’t want the naturally immune to be a control group.

They don’t want anybody to be a control group.

Yup, among all the other evil and folly at play, I suspect this is the case – the longer this goes on the more they are realising the vaxs don’t work and they are desperate to cover it up.

Yes exactly so. A large group of the unvaxxed refusing to die would be very dangerous for them and could easily give their depopulation game away. Consequently they will go to great lengths to coerce the “vaccine aware” into taking the needle.

By the end of the summer, they may just be desperate enough to push for mandatory vaxxing of all, even though they know this would likely cause them massive trouble.

Of course, there is no viable alternative to staying unvaxxed and continuing resistance remains vital.

And not dying.

I wonder if the next (UK) tactic will be to say that the medicated pose a threat to the unmedicated since they are more likely to pass it on, and of course the unmedicated group is made up of those who are so vulnerable as to be exempt, and those ‘selfish refuseniks’. By the way, the old chestnut they’re throwing in at every opportunity about offering everyone the meds likely means it’ll be harder to argue for discrimination. So the unmedicated must absolutely be kept away from the medicated, for their own safety and protection. Backed up by liability insurers of course. Another step towards Ihren Pass bitte.

And that is why whatever they throw at us all we need to do is hang on long enough to discredit them. I can live without going to the theatre or pub for a year – especially with all the private parties and underground gigs etc that we run for each other. The story is crumbling, slowly but noticeably. The anger and spite of the pushers is not the sort of thing you see in a confident enemy. They know that if they fail now they are done. The next six months are our Stalingrad and I will go through anything to beat these cunts.

I too will stop at nothing to beat these cunts.

Ironically, in some ways my social life is better this last 16 months than it has been before. And we will stick together. And remain human. And beat these…

Spot on.

Stupid policy if so, they’ll never get everyone. I suppose they might try and make up some way of casting doubt on a small control group…

Good article

Even if the experimental vaccines provide some short term protection but that fades quite quickly, perhaps for the reasons given in the article, then presumably the booster protection will also fade quickly. And then the booster to the booster protection will fade quickly. And the booster to the booster to the booster protection will fade quickly.

Whichever way you look at it the experimental vaccines aren’t working it seems.

Meanwhile each experimental vaccination subjects the victim to the harmful affects of the spike protein. It’s just kicking the can down the road while prolonging the huge societal damage of not letting the virus run its natural course into an endemic state. Much better to get the thing over and done with through natural infection.

I said right at the start that the virus will do its thing regardless of what we do..

If they had taken that approach back in March 2020 this would all be over and done with now.

What? The experimental jabs don’t work, quick wheel out the booster jabs before the lab rats notice

The CDC has approved boosters now, given the short term efficacy of the stabs. Could there possibly be any link between this result for shareholders and the willingness of Israel, aka (alas) the State of Pfizer, to admit they are imperfect?

And how is this twist in the narrative going to go down here? Will faith in The Church of Science begin to weaken? I think it must for some, even when the preaching of fear begins big time in late August. Many people had bad effects from their stabs, and won’t want a third. Others now know people who got badly sick even when double “vaccinated”. Heresy must be growing.

The story is falling apart. Almost everyone I know who took the jab did so on the basis of that being that. And almost everyone I know who took the jab is now wondering why they bothered.

We win this, we destroy those responsible.

I’m not so sure there will be as much enthusiasm for a booster as the original jab in the under 50’s.

The unvax’d control group presents a serious risk to the narrative. Maybe that is why the vac passport coercion is needed before they fire up the ovens?

Yeah lots of jabbed I know are saying they won’t get boosters.

First question for vaxxed should be how long will the booster last then? 3 months? Six months? Until a variant that evades it again?

Seems like a cycle that will never end.

Exactly

We’ll see. I know many many people who didn’t want to get vaccinated but did so because they didn’t want their lives to be limited. In fact, pretty much everyone I know who has been vaxed has done it of that reason and that reason alone. If they weren’t willing to fight the first time around, I’m not sure they will be willing the second time around with even more invested in the process.

Yes indeed. The unvaxxed are the real threat to the hardly sustainable vaccine narrative and they will likely try everything short of forced injection as we roll into the autumn. If that fails, we can’t rule out mandatory vaccination for all and though that would raise hell, it may be the distraction they want as the vaccine injury deaths pile up. Things are looking very serious, with no soft landing likely for any of us, but perhaps least of all the government and its cronies.

“The sharp drop in the proportion of older people being hospitalised since spring in the U.K. (the 65-84 cohort’s share has dropped from 40% to 22%) compared to younger people (the 18-64 cohort’s share has grown from 37% to 64%) is also an indicator of protection from serious disease (see below), as older people have higher vaccine coverage.”

Tunnel vision thinking. Get out of that subservient box!

It might be. They certainly want you to think it.

But it might not be — the ‘as older people have higher vaccine coverage‘ isn’t necessarily as simple as you think — eg, according to official stats about 1/4 of those 50+ and unvaccinated are >80, compared with about 12% of the vaccinated >50 group.

So if there is a simple age effect where to 80+ group are more likely to die regardless of vaccination status, this will show up as a greater effect in the unvaccinated group compared with the vaccinated.

This sort of effect could very easily be misinterpreted as evidence of vaccine effectiveness.

A new study in the Lancet has shown that antibodies from the vaccines notably decline over the course of three months,

Isn’t this what is taught in first year medical school, seem to remember a lot of people saying so last year.

This is a post about the safety of the covid vaccines.

Public Health Scotland have stated that 5,522 people have died within in 28 days of having a covid jab. This was between 8/12/20 and 11/6/21(Global Research, 22 July 2021).

What is the significance of this figure? Below is my ball park calculation. I have made one major simplification.

Probability of a man/woman aged 50 dying in a given year = 1 in 350 =0.003

so probability of dying in a given month = 0.003 divided by 12 = 0.00025

Adult population of Scotland = 4,500,000

Expected number of deaths in a month = 4,500,000 x 0.00025 = 1125

Simplification: suppose all covid jabbing had been done at the same time and that the 5,500 deaths occurred with in 28 days of this.

Using this simplification the actual number of deaths following the jab is five times the expected number. Perhaps someone can make an improvement to this simple calculation

PHE have refused to reveal the number of deaths within 28 days of a covid jab in England.

In my view the covid vaccination programme should be halted immediately. A number senior politicians and scientists should promptly resign.

I’m in no way pro this so-called vaccine but what do the odds of a 50 year old dying have to do with it unless all the vaxx deaths were 50 year olds?

Roughly 5000 people die every month in Scotland so at face value 5500 is not exceptional over several months just as the with/of covid deaths were not exceptional.

We need to know more details of those dying post-vax to be able to draw any real conclusions as to whether they’re really killing people. I have a feeling they’ll make that sort of information really difficult to come by.

I picked a 50 year old as being roughly in the middle of the age range. I am only trying to make sense of the PHS statistic with limited data. I strongly suspect more information would confirm how dangerous the covid vaccines are.

5000 plus is nearly 10x the number of people who are reported to have died ‘with’ covid in Scotland over the same time period. That is the ONLY statistic you need to look at. Pro-rata the number dead after 28 days of vaccination in England would be over 50,000.

they started oldest and “most vulnerable” first so you’d naturally expect a number those people to die in the next 28 days jab or no jab.

A monthly breakdown would be far more telling. if it’s similar numbers each month as the jabbees are getting younger then that would be a better indication of a problem.

Yes. They’ve made any sort of analysis of the data incredibly difficult.

I am appalled by it all. All the advice last summer was that using a vaccine with very short development timescales necessitates robust pharmacovigilance. This doesn’t mean the extraordinarily poor yellow-card system (and similar for different countries), but active follow up of every vaccination (with perhaps more details taken from a sample). The authorities ignored this advice and were instead determined to not look.

But then, politicians know all about ‘plausible deniability’ — if there’s no data collection then there won’t be any data to worry about.

How many people have died or had lifelong complications following the vaccines? Perhaps none, perhaps 1:1,000. We won’t know because we’re not looking.

Well, I suppose some scientific papers will come out at some point, and the politicians will exclaim ‘but we didn’t know!’ and ‘we trusted the science‘. And it’ll all be too late as they’ll have had their glory and payouts, the vaccine developers will have made their millions and there won’t be anyone left in the world unjabbed.

“I suppose some scientific papers will come out at some point” Not much hope of that. Too many people from top down, too many powerful and collaborators, up to their necks in this. I think we’ll have to leave the true verdict to historians.

A good analysis, amanuensis.

“They’ve made any sort of analysis of the data incredibly difficult.”

This has been a general feature of the panicdemic in general – to the point that there is no good evidence of the extent of real infection, the incidence of the secondary issue of ‘Covid’, and the mortality from it.

One could attribute this all to incompetence – but, for instance, the continuing use of the critically flawed PCR testing for ‘diagnosis’ in the healthy population suggests otherwise.

And, of course, lets not forget the fact that the case for emergency use of the ‘vaccines’ rested on a direct, documented lie (let’s not wrap it up) – that we were facing an ‘unprecedented‘ emergency. That we weren’t could be ascertained with a simple historical spreadsheet and basic mathematical nous.

So you are absolutely correct about the smoke blown over any data concerning the snake oil. By definition, these concoctions cannot be declared ‘safe’ by accepted criteria. It’s a contradiction in terms, and even the most basic enquiring mind should be able to work out that on-going RCT data has been compromised, and that observational data cannot provide any satisfactory experimental framework.

Furthermore, the warning lights were flashing when there was some viable data. Apart from the incidence of harms, Israeli data pointed up a crucial figure : the exceedingly low absolute risk reduction figure. This was concealed in a PR operation that blew up ‘efficacy’ by quoting only relative figures.

It is interesting that the latest Israeli data (above) is tending to confirm this trial calculation in a comparison of the vaccinated and unvaccinated.

So – the data does emerge, but is covered over by obfuscation and governments turning themselves into PR agencies for the pharmaceutical industry, whilst inhibiting any other possible means of prophylaxis and moderation.

The evidence for just simple incompetence and confusion shrinks by the month.

Resign? Go to jail more like.

If the PHE refuse to reveal the number of deaths within 28 days of the jab, it looks highly likely they have something to hide.

Panic ye not, fellow cattle, for we already have approval for the quick rollout of tweaked and unvetted variant beating boosters! Our pharma farmers truly have thought of everything, bless them. Granted, going to a McJabbo Drive-Thru every month is going to get inconvenient pdq.

That’s why before 2022, we’ll move to a Jab-by-Post/NetPrix™ delivery system, so you can receive a daily consignment of 24 essential subvariant updater doses without any fuss, freeing you to face each new (and highly dangerous) day a little more safely.

But what of 2023? To deal with the microvariants, we’re going to need JabDrip®, a constant jab delivery system that attaches directly into your spinal column. Simply strap the ViroSafe™ reservoir to your hip like a colostomy bag, and then whenever you pass a ViroSafe™ HealthNozzle™ (there should be one every 100 yards in busy areas), you can top up your immunity on-the-go, just like a mid-air refuelling fighter jet! Whooosh!

“If you want a picture of the future, imagine a needle stabbing into a human arm – for ever.”

I see a flaw! The Grand Jabberwocky wouldn’t be able to tell in this case whether the recipient had in fact blindly done as instructed, or had flushed them down the toilet. And as we know, they really don’t like leaving people to make their own decisions – and if they don’t know who hasn’t taken “advantage” of their NetPrix enforced subscription, how would they know who to harass with text messages and letters, and try to exclude from society? It’s essential that they can identify those who don’t behave like good little sheep, as the whole programme is dependent on the existence of people who don’t “follow the rules” who they can use as scapegoats…

Covid vaccines routinely thrown in the bin as not enough people are coming forward – Once thawed, the Pfizer and Moderna shots have a maximum shelf life of up to one month in the fridge ~

(NO MENTION IN THE GATESOGRAPH ABOU THE WORLDWIDE RALLIES)

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/07/24/covid-vaccines-routinely-thrown-bin-not-enough-people-coming/

Stand in South Hill Park Bracknell every Sunday from 10am meet fellow anti lockdown freedom lovers, keep yourself sane, make new friends and have a laugh.

Join our Stand in the Park – Bracknell – Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

HOME EDUCATION – Ex-Primary School Teacher on Resistance GB YouTube Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZ5oS2ejye0

https://www.hopesussex.co.uk/our-mission

When Pfizer first made their data available, a quick calculation of the absolute risk reduction, 0.7%, was enough to conclude that their ‘vaccine’ did very little, so why all this information coming from Israel is causing such bewilderment is anyone’s guess.

Because most people can’t do maths beyond the most basic arithmetic.

We’re just not designed to think in terms of big numbers or fractions, which is what is needed to make sense of life on the modern day scale.

… and why ‘common sense’ is just crap when it comes to proper analysis … but a massively effective tool for fakers.

Just like ZOE app, how can we trust coronavirus.gov.uk plot on the change of age ratio of hospitalized for c19. There’s also the question what is meant by “c19 hospitalization” – is it someone with symptomatic c19, someone with a positive c19 PCR test with no c19 symptoms who came to hospital for something else, or some who just picked up c19 in hospital (in most cases not worsening the problem for which they came to hospital) or everything combined. Then the ratio might be more due to how these errors have changed than real c19 hospitalizations.

In any case the IFR for <65 was always small (especially for healthy) and this didn’t change over time with new named micro-mutations (the variants), and many already had it or are not even susceptible.

C19 hospitalisations are like C19 deaths – positive test, regardless of what you were admitted for. Gove admitted a few months ago they had no real idea how many people were in hospital actually suffering from covid. I think Hartley-Brewer asked him. The fact that such an obvious question cannot after 18 months be answered tells you all you need to know.

“England data include people admitted to hospital who tested positive for COVID-19 in the 14 days prior to admission, and those who tested positive in hospital after admission. Inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19 after admission are reported as being admitted on the day prior to their diagnosis. Admissions to all NHS acute hospitals and mental health and learning disability trusts, as well as independent service providers commissioned by the NHS are included.”

https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/healthcare

Note that for “cases”, “People tested positive more than once are only counted once, on the date of their first positive test.” Thus, someone with a historical positive, who receives a subsequent positive result, months later, would not add to the “cases” total, but might still qualify for “Patients admitted to hospital”.

Brilliant stuff, including Dr Robert Malone dropping a few truth bombs –

https://rumble.com/vk9rmy-episode-1120-dirty-dozen-the-12-most-dangerous-people-in-america-pt.-1.html

My cousin (27) had his first jab a few weeks back – now on antibiotics for a chest infection – never had a chest infection in his life – strange but lots of family members coming down with all kinds of ailments like sore throats and cold-like symptoms – vaccinated brother had a mild case of flu a couple of weeks back and took a couple of days off work … maybe its just the changeable weather ? I dunno? But I find it very odd that I am the only one not to have had the jab in my entire family and amongst my small circle of friends and so far I’m the only one who has not so much as a sniffle so far – absolutely nothing – perhaps I’ve just been extremely lucky for the past fifteen months – but I’m out cycling every day five days a week and interacting with many people on my travels and I’ve not had so much as a bodyache or a sore throat etc. Meanwhile the jabbed ones all around me are coming down all kinds of mild medical conditions and assorted bugs.

Weird?

We know FAR more people hospitalised from the wonder jab than we know affected by CovEbola. This is the truth that I think a lot of people are experiencing and hopefully will help turn a corner.

Paraphrasing Orwell – ‘the party told you not to believe what your eyes see and your eyes hear’

I botched the same thing, many jabbed are coming down with bad colds and chest infections. Could all just be entirely coincidental though.

That’s because they didn’t have their flu vaccinations.

Well that’s what we will be told, but I suspect the jabs are intended to defeat the natural immune system.

All in all, it seems vaccines have much lower than advertised effectiveness and with huge uncertainty. So, mandating them is not just wrong but useless (even if c19 was some ugly disease).

Saying that vaccines lower the severity of the disease and therefore the potential to spread it (lower viral load in a sick person and the amount of coughing), is like saying that obese, old people, etc. have a higher chance of infecting others since they are more likely to have serious illness (and higher viral load). Then, together with the unvaccinated, they could ban also obese and old people (vaccinated or not). Basically, they could do any kind of mental gymnastics and twisting in order to justify anything they want.

c19 and corresponding “vaccines” can mean anything and nothing. They are like clay, they can be molded in whatever way to justify anything.

forgot to mention that weird “study” that allegedly found bold man are more likely to have more sever c19. So, they could ban them from traveling or entering for “public health reasons”. They can chose any group, make a fake study and use it to repress them and ban their basic rights.

Do you mean bald men? There are not many bold men around nowadays.

I think mandating vaccines is a bit like mandating lockdowns – the circumstances in which it might be morally justifiable are so extreme that they would in practice not require any kind of mandate. If you need to mandate public health measures for the benefit of people other than the recipients then the “emergency” is probably not actually that much of an emergency.

Giving governments power to do any such thing is just a bad idea. They can’t be trusted. However safe or effective a vaccine is, it must be a personal decision.

Agree with both comments.

ps. spelling error: “bald”, not “bold”.

I’m balding and bold 🙂

I believe the unmasked have a better chance of avoiding covid, no suppressing of the immune system

This is all totally predictable. The ARR of the trials was approx 1% for reduction of one symptom. There was nothing at all about immuntity or transmission.

The only reliable way of getting immunity from a respiratory disease is to catch it and get natural immunity , ie T-cell response that lasts.

Of all the news about the 100,000s of people out on the streets in France today the most unexpected and heartening were the people bringing Annecy to a standstill. Now anyone who knows France will know that just about the last place to expect any sort of demonstration is the picturesque , sleepy Annecy in Haute-Savoie. Yet here there are..

https://www.francesoir.fr/actualites-france/manifestations-pour-la-liberte-annecy-une-foule-heteroclite-au-milieu-des

Do Not Believe the Media!

BE HONEST WITH THE TV MEDIA! Recognize that this day of FREEDOM has won a

stratospheric ” (fashionable definition) success over 2 million French people in the streets of more than 170 cities in France. By counting the gatherings filmed on video, the count could reveal nearly 3 million people (women and children included) to regain their FREEDOMS!Thank you for this attachment to democracy by fighting against this tyranny.

LET’S CONTINUE THE MOBILIZATION:

1) IT’S THE TIME TO SIGN THE PETITION (3 million to act)

https: // petition-pass-sanitary (dot) com

2) PERSONAL APPEALS from next week after knowing the number of the law An appeal against the Health Pass (for everyone):

https: //www.divizio (dot) en / recourse / recourse-pass-santé /

This is typical of thousands of individual messages flooding across France tonight.

”The mainstream media are in panic! They no longer even have the calm enough to disseminate false figures but at least credible for the naive. In my small provincial town alone (Avignon in the middle of the holidays) there were at least 5,000 people!

And in addition, many of the surrounding small villages even had their own demonstrations. It is no longer even a giant wave, it is a tsunami of freedom!”

Entirely agree on the ZOE data – no credibility left – no doubt they will gain high marks in the next REF for Impact ( just not sure what impact useless data has – actually I am – what the original less adulterated data showed was symptomatic infection was levelling which will hopfully very shortly affect the trend of hospitalisations)

Depressing to see Gareth Southgate urging youngsters to ‘get the jab’ in order to ‘get your freedom back’. In other words, do as you are told, kids, or restrictions will continue. That sounds a lot like coercion to me. Not terribly sporting, really.

He’ll probably wished he kept out of it in the future

Yeah – it’s his Nazi salute in Munich moment

Could he be taken to court as coercion if illegal? If a few high profile people fall foul of the law it might make other brain dead celebrities think twice before spouting off.

I was interested in the BBC ‘pulling’ the story from its website quite quickly (though of course, it can still be found via your favourite search engine). Further trolling around the internet revealed that Mr Southgate’s ‘pronouncements’ were, in fact, issued by No 10.

I think they have this weird view of what us plebs are interested in … his day has been and gone for the time being. They’re about two weeks too late. So far as I’m concerned, the England manager can get back in his box for now; I’m more interested in who my team/s have signed for the coming season.

Chinese style social credit score system incoming.

https://youtu.be/DlnA6fDJsi4

The beast system is here

another link https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/07/23/families-could-get-rewards-healthy-living-new-war-obesity/?WT.mc_id=tmgliveapp_iosshare_AxgCq827TjCN

but it’s all just a conspiracy theory. baa ram ewe.

So basically these amazing new jabs are just cold medications. Reduce symptoms and that’s about it as far as I can tell

True. And very few people end up in hospital when they get a cold.

Made little presentation about the vaccine safety issue

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1vQqmseLv6REmHyIKRscQ1_ZO77vyw_WHADJttSqQWMY/edit?usp=sharing

Estimate 111 death per million doses

Rsquared for regression 0.95

I wonder, almost every day, what the powers that be will think up if the longer term effects of these vaccines turn out to be disastrous?

There are too many reputable scientists urging caution and some suggesting that the damage is already done for there to be “no cause for alarm”.

What I also wonder, every day, is whether SAGE and the Government ever bothered to read The U.S. Pandemic Influenza Plan, current edition published in 2017; following on from the plans published in 2005 and 2009. These plans were prepared by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (HHS). I fear it is the Bible they’ve all been reading from. Can I suggest, before you lose the will to live, You all read it; all 52 pages.

HHS is a Federal organization which draws in just about every other Health, Security and

Public Control departments in the US government.

The first line of the Conclusions is telling; “As the 2017 Update demonstrates, HHS has made progress in pandemic influenza preparedness over the past DECADE.”

For 12 years the US have been preparing for this eventuality.

I could be mistaken but for me they have taken parts of their plan and binned much.

Sound familiar?

“If?”

We clearly already have ADE/PIE (as a result of a high level of population exposure to coronaviruses in general and the latest specifically) caused by vaccination of people already having an immune system primed by the virus. The evidence was shown a couple of months back when someone researching the VAERS db looking for deaths where the jab date was on the file entry created a graph that showed and immediate huge spike in deaths in the first 24h followed by a tailing off over a week or so to background levels. I kept a screenshot of the graph but the site that published it has vanished – I wonder why.

Conclusions are on page 40.

You can be sure that they will come down hard on the unvaxxed now to cover up the inadequacy.

The attacks will come on 4 fronts:

1, Economical- no jab, no job.

2, Peer pressure-social outcast if no jab.

3, Social- no access to clubs etc.

4, Familial- pressure from own family.

People who have been conned into the vax route will never admit they’ve been had or give up their sense of moral superiority through doing so (the reality is that they only did it to go to Spain for a fortnight). Sure a minority will but most won’t.

At the moment, I am suffering my spouse going on ad infinitum about this.

I talk about this in the language of war because this IS a war now.

I wrote a comment a few days ago where i conjectured the strange infection dynamics we are witnessing are because Covid-19 lives in the hinterland between the Dermis and the Epidermis, where there is insufficient blood flow for the immune system to get to it and remove it, but where there it can’t either so effectively replicate (but it can still replicate – just not freely). I propose this based on research i read into how an infection develops in the body, effectively spreading along the skin until it reaches and takes over the lungs and because it provides a parsimonious explanation for the differential infection rates in the vaccinated and unvaccinated. After all the vaccinated and unvaccinated don’t live in separate countries. These infection rate differentials we are witnessing cry out for an explanation.

If I’m right, the vaccines can’t prevent infection at the “hinterland” level. Rather they are effective at preventing the virus entering deeper into the body. But covid can replicate – albeit slowly just outside the reach of the body’s immune system.

The overweight have a greater mass of skin with poor circulation. Meaning they have a much larger reservoir of the “hinterland” covid needs to survive. It is a weak virus easily killed once properly “in the body.” I propose it only becomes a problem when the viral load living in the hinterland is such that seepage into the body goes beyond a threshold the body can cope with.

I conjecture Positive tests are occurring when there is sufficient accumulation of the virus such that it is continually leaking into the blood supply. The strange national virus infection dynamics we see become explicable when we think of infection being based on accumulation in this hinterland. The vaccinated infection rates lag the unvaccinated because sufficient accumulation before the virus can no longer be staved off from being registered “inside the body,” takes longer in the vaccinated. Also the manner in which new variants “take over” from earlier variants becomes more readily explicable.

Clearly if this is right, confined spaces are required to add to the accumulation. I also conjecture air filters that can filter to the virus level will be very effective if deployed in pubs clubs etc. The flow of aerosols is not intuitive to the average person. At the aerosol level particles equalise very quickly indeed. Infection will be ocuring when a threshold general load is exceeded and not from being breathed on or even from spittle (again the strange infection dynamics of Covid reflect this being the case). Air filters can very quickly process the air and will lower the general “equalised” viral load in confined spaces extremely effectively.

It also becomes clear why there are no apparent cases of outdoor transmission (so few apparent cases of outdoor transmission as IMO likely purely mis-analysed cases – where in fact the cause was indoor transmission. Sufficient accumulation simply can’t occur outdoors.

The young have young skin and great circulation with minimal hinterland

This also explains the “time to infection” phenomena where infection seems to occur where people are in a place of congregation for 15 or more minutes. This has always just been kind of ignored without being adequately explained. You don’t need 15 minutes of exposure to catch a cold or the flu. You only have to touch an infected handrail and touch your eyes just once. By contrast it is known fomites are not the vector of transmission for Covid-19.

I would also conjecture the infection pathway will be via the lungs, but the lungs are relatively well serviced by the blood supply, so replication occurs in the hinterland beyond the lungs, before returning to the lungs if the body becomes overwhelmed by it.

Lastly the fact of Long Covid becomes more explicable. We rarely fully rid ourselves of it and remain in a constant war, much as the body is in always in a constant war with pathogens entering through the skin from the epidermis. The epidermis is a massive shield preventing most from entering (but not all). It is my opinion Covid could simply be one that is better adapted to accumulating and replicating there at the boundary just out eh of reach of the immune system.

I got carried away and forgot my main point! And that is that this also fits with what we are observing now. That new variants are able to transmit (they live in the Hinterland) but not cause serious illness in those who have better immune protection. This “model” for how the virus works also provides an explanation for the fact transmission and illness are so oddly distinct. Transmission isn’t prevented. But the immune system does prevent deeper entry into the body, so the vaccinated or those with antibodies are less likely to succumb or develop complications.

Interesting. Could this potentially be an explanation as to why IVM (an anti-parasitic) works well when administered correctly and at the right time?

What they are trying to effectively make mandatory “vaccination” isn’t because of the virus. It’s so that the globalists can develop their health surveillance/social control system.

My wife and I went to a restaurant last night – first time since before this shit show all started. We got a taxi home and the subject of vaccines cropped up. The driver said he’d been double jabbed, but only because the taxi firm he worked for expected it and he didn’t want to lose his job. But, he said he didn’t want the jab and added something along the lines of: ” . . and I’ve no idea what’s in it – could contain anything for all I know”. I suspect many feel this way and, as others have commented here, I think take up of future booster jabs etc. will tail off and, one by one, people will realise they’ve been conned.

Yesterday, a relation of mine told me the reason why his father-in-law had recently died – which was the adverse response to the ‘vaccine’. He then asked me if I had taken the jab. “No”, was my answer and I explained the reasons why. He then looked at me unbelievably, moved away, and could not grasp my reasons.

So, the fact that he knew the ‘vaccine’ killed his father-in-law and that they can be lethally dangerous, he still thought taking the ‘vaccine’ was a good idea. Cognitive dissonance at its finest. What has happened to people’s minds and rational thought processes?

Sadly this reaction is all too common. The public brainwashing by SAGE at al has worked wonderfully. At inpot dictator would be proud – but then again perhaps BOJO is?

Interesting campaign in the Mail to spotlight China … but not attack the basic narrative.

So we have ‘asymptomatic spread’ raising its befuddled head again. Mmmmmm….

A MUST watch. Vaccines are backfiring on the populace:

https://rumble.com/vk8cpw-top-american-doctor-covid-shots-are-obsolete-dangerous-must-be-shut-down.html

To sum up, it just does what it says on the tin, not what certain politicians promise and so on, if you just browse the paperwork issued to us inviting us to have the jab. Not only that, the more evidence there is that demonstrates the truth of it’s efficacy (or not), the wider the gap is between risk and benefit to many of us, setting aside coercion for the time being.

When you read the leaflet they give you after the jab it says clearly at the end that you should still keep to the social restrictions and mask wearing because the jab does not guarantee protection from covid19 and that you can still catch and spread the disease – but people don’t read this information – they roll up their sleeve, take the jab because Boris has told them to in order to stop the spread and protect them from infection when it is doing nothing of the sort – it may ease the symptoms but despite that its little more than a glorified Lemsip – but people have the jab (or two) and think ‘thats it I’m protected – I can’t get covid now I’ve had both jabs‘ – then shocked to discover they have tested positive for covid and what makes this discovery even more unpalatable is that many are completely unaware that these are trial vaccines – never been used before – very few people are aware of this and have been misled into beleieving that this vaccine is just like the flu jab (how many times have I heard that one – even in doctors surgeries) and no one knows what the mid-long term affects will be – the risk of developing a permanent and even serious health issue due to the vaccine are real and appears to be quite a risk to take for something that doesn’t even guarantee you won’t get covid – judging by the symptoms and the chances of me dying from covid19 (about the same as flu) I think I would rather risk the virus than the vaccine.

Aye. Don’t trust the ZOE app. They get to everyone

Re the comment about not trusting ZOE graphs anymore, I felt that their changes might be justifiable if the graphs were then similar to, but pre-dating, the gov.uk graphs. But I think ZOE must have over-compensated somewhere, because although their original downturn appears to have been too soon (around July 10), their lack of downturn now is not credible given that gov.uk cases have been falling for about 5 days. It’s going to be interesting to see how they rationalize that situation. Possibly they will say there is another upturn due soon, and be right. But more probable is that they have messed up somewhere.

The problem is after all the propaganda, lies and deliberately distorted modelling we have had to endure, I ask myself who benefits from this latest “data” and once again it is big pharma companies. We need to have our max. sceptic shields up until there is a wider analysis of whatever is being said, and we can extract the real truth.

After all the propaganda, lies and deliberately distorted modelling we have had to endure, I ask myself who benefits from this new “data” and once again it’s big pharma companies. We need to have our max. sceptic shields up until there is wider analysis and the real truth can be established.

Excellent conclusion. There is no other sensible way forward than to just get back to normal.