The Prime Minister may have acknowledged reality and stated that being double vaccinated “doesn’t protect you against catching the disease, and it doesn’t protect you against passing it on” but others appear to remain in denial.

On Sunday I asked whether now that the PM had let the cat out of the bag the media would start reporting properly on the UKHSA data showing higher infection rates in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. It appears the answer is no, at least if the Times‘s Tom Whipple is any indication.

In a typically mean-spirited piece – in which anyone who doesn’t agree with his favoured scientist of the hour is smeared as a conspiracy theorist and purveyor of misinformation – Whipple quotes Cambridge statistician Professor David Spiegelhalter, who heaps opprobrium on the U.K. Health Security Agency (the successor to PHE) for daring to publish data that contradicts the official vaccine narrative. Spiegelhalter says of the UKHSA vaccine surveillance reports:

This presentation of statistics is deeply untrustworthy and completely unacceptable… I cannot believe that UKHSA is putting out graphics showing higher infection rates in vaccinated than unvaccinated groups, when this is simply an artefact due to using clearly inappropriate estimates of the population. This has been repeatedly pointed out to them, and yet they continue to provide material for conspiracy theorists around the world.

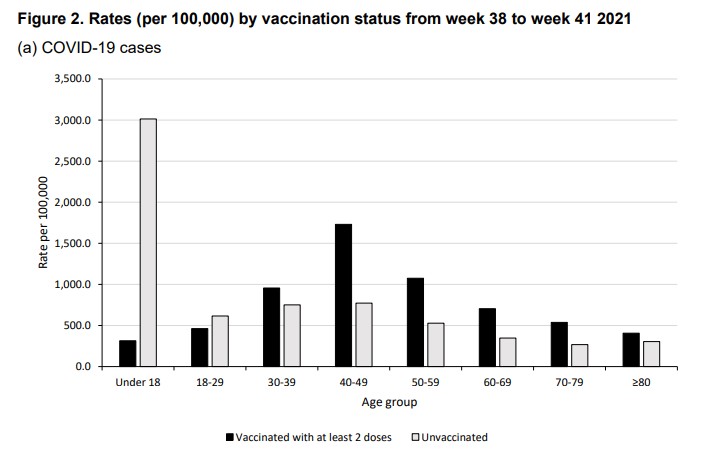

This is the graphic he is presumably referring to.

If Professor Spiegelhalter has a source for his claim that higher infection rates in the vaccinated are “simply an artefact” of erroneous population estimates then he doesn’t provide it.

Whipple says the data has been “seized upon around the world”.

The numbers have been promoted by members of HART, a U.K. group that publishes vaccine misinformation. They have also been quoted on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in the US, which reaches 11 million people.

Appearing on that podcast, Alex Berenson, a U.S. journalist now banned from Twitter, specifically referenced the source to show it was reliable.

The UKHSA is adamant that it is doing nothing wrong. The Times quotes Dr Mary Ramsay, head of immunisation at the UKHSA, explaining: “Immunisation information systems like NIMS are the internationally recognised gold standard for measuring vaccine uptake.”

So Professor Spiegelhalter thinks that the gold standard gives “clearly inappropriate estimates of the population”, and using it is “deeply untrustworthy and completely unacceptable”? That may be his view, but the UKHSA can hardly be criticised for following the recognised standards for its work.

A more measured criticism is provided by Colin Angus, a statistician from the University of Sheffield, who the Times quotes saying that using NIMS data makes sense but the “huge uncertainty” in the population estimates should be clearer.

Whipple, however, goes further and claims that “using population data from other official sources shows, instead, shows that the protection of vaccines continues”. Yet he does not provide those sources or go into any detail about how they back up his claim.

For now, the UKHSA is defending its report (we’ll see how long it holds out for). But even so, Dr Ramsay is adamant that the report rules out using the data to estimate vaccine effectiveness: “The report clearly explains that the vaccination status of cases, inpatients and deaths should not be used to assess vaccine effectiveness and there is a high risk of misinterpreting this data because of differences in risk, behaviour and testing in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations.”

This defence somewhat misses Professor Spiegelhalter’s criticism about population estimates. But it’s also misleading in that the report doesn’t “clearly” explain that its data “should not be used to assess vaccine effectiveness”. What it says is it is “not the most appropriate method to assess vaccine effectiveness and there is a high risk of misinterpretation”. But, as explained before, using population-based data on infection rates in vaccinated and unvaccinated is certainly a valid method of estimating unadjusted vaccine effectiveness, which is defined as the reduced infection rate in the vaccinated versus the unvaccinated. While a complete study would then adjust those raw figures for potential systemic biases (with varying degrees of success), we shouldn’t necessarily expect those adjustments to be large or change the picture radically. Indeed, when a population-based study from California (which showed vaccine effectiveness against infection declining fast), carried out these adjustments the figures barely changed at all.

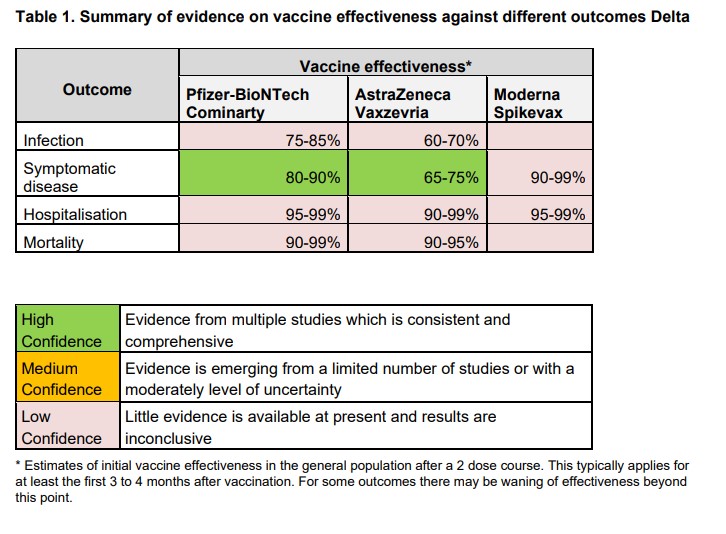

The UKHSA report adds: “Vaccine effectiveness has been formally estimated from a number of different sources and is described earlier in this report.” In fact, though, most of those estimates are reported as low confidence (see below), which means: “Little evidence is available at present and results are inconclusive.” While it claims high confidence for its estimates against symptomatic disease, a footnote explains that this only holds for 12-16 weeks: “This typically applies for at least the first three to four months after vaccination. For some outcomes there may be waning of effectiveness beyond this point.”

It is precisely this “waning of effectiveness” that the latest real-world data is giving us insight into. Rather than trying to discredit that data and those who report it by throwing around general, unquantified criticisms, scientists and academics like Professor Spiegelhalter should be redoubling efforts to provide constructive analysis to get to the bottom of what’s really going on with the vaccines. If there are issues with the population estimates then those need to be looked at, and if there are biases that need adjusting for then those need to be quantified. But do, please, get on with it – and lay off the smearing of those who raise the questions.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Who the flipping hell do these two think they are? And even if they were ‘anyone’, who the flipping hell cares what they think?

These two walked away from responsiblities and obligations (as if dressing up nicely and shaking a few hands now and then is anything remotely resembling a responsibility) so they can just wind their necks right in.

I’ll tell you who has to deal with responsibilities, Ginge and Whinge; the poor paramedics who tried their damndest and failed with 22-year-old Paul Parish at yesterday’s Fulham game.

Just STFU.

I think you may be missing the bigger picture.

It’s clear that Rogan has enemies, as does anyone public and with certain power. Neil Young’s random shot at Rogan has been picked up by them and they’re testing to see how much damage they can do to him.

No doubt they’ve gone to look for some poor, publicity craving dopes to do a bit of sniping and they’ve landed on these two idiots.

All this shows is how utterly insignificant and irrelevant they are. Neil Young and Joni Mitchell followed by Harry & Meghan. That’s who they are barely a step up from. The next level of “celeb” to try to turn the heat up on Rogan.

But it is interesting to see how much momentum this will get. I have no doubt that they would love to take down an independent voice like Joe Rogan’s. That would definitely push the plebs back into their place even more. After all, that’s what all this is really about. Just another sub-plot of in the general effort to stamp down on the pesky plebs.

Lol, I don’t think there’s any point to miss where these two are concerned. They are just a couple of rent-a-gob whining children, available to the highest bidder. I suppose it might be interesting to find out which of their ‘co-founders’ might have paid them to go out and big up the jabs, because this is what their ‘statement’ amounts to, but I lost the will to live reading the Wiki page for ‘Archewell’. What a complete load of old flannel.

They are nobodies with big mouths, just monestising links they no longer have to a family and a country they turned their backs on.

It was once said of an Australian politician’s ex wife that she was a publicity chaser who would show up at the opening of an envelope. This pair put her in the shade.

Absolutely, I am sick to the backteeth of any coverage of Ginger and Whinger .I did not care one iota for what they thought or said when here and I care 1000 times less now they are not.

Can we add any coverage of them to the profanities list please Toby

Ginger and Whinger. Perfect!

Who the flipping hell do these two think they are?

It’s not who they ‘think they are’ – it’s who they actually are : ‘influencer’ trivia who have tremendous pull on the lame brains who read Hello and the trash press, hypnotised by the glitter of royalty in this Ruritania.

They are more bottomfeeders than people with influence. If they had influence they’d exert it rather than going with the flow and basically saying “What Albert Bourla says! Us too!”

As far as I’m concerned, that’s Prince Pantsdown and the lady capable of making really convincing arguments with her mouth :->. Hardly people whose opinions on anything would matter. Moreover, he doesn’t really have any, and she just repeats whatever her comwokiots consider commes ils faut.

NB: Insofar I have any political opinions, I consider myself a monarchist. But that doesn’t mean I believe that each wayward scion of some royal family must belong to a superior species of man.

Was he only 22 😢

Nice to encounter people of real depth, intelligence and integrity

Any opportunity for a bit of exposure………………

Good point. They’ve got a publicity budget, they’ve got staff who keep track of their profile, and if they’ve been off the front pages for a while…

Away and boil ya heeeds ya fekin tubes!

Sage advice that I fear will not be heeded.

Clearly 77th. A true Glaswegian would spell it “heids”.

^ Joke 🙂

Nah. Bollox is OK, Ya ken.

Just his English enunciation, dontcha ken.

Prince Harry is going to turn me into a republican.

Uncle Andy hasn’t already?!

In my case, no, but the Queen’s climate change outburst did, in a nanosecond.

No for me it was when she said everyone had to be jabbed.

Yup that was a disappointment.

Yes.

What the f. would a voice for the establishment be expected to do?

She could just avoid commenting! The clotshot is now very much a political issue as the queen is generally fairly adept at avoiding controversial political topics.

Sorry CR – you beat me to it.

Say nothing at all if she was at all concerned that what she might be saying was “political” and controversial – this from a woman who has spent the bulk of her adult life trying to make sure that the monarchy stays out of politics

Her late husbands influence, me thinks.

me too that was it.

The whole family is toxic.

and prince charles too. how could he be for the’jab’ he ‘s against GMOS

The wankers did it to me years ago as the late great MrBourdain said those gates would look better with their heads on,standing outside buck palace.

The scientific genius that are Meghan the equivalent of a Coronation street actress and a Prince who I believe achieved 1 Alevel in Art obviously can debate with Peter McCullough and Robert Malone with regards to the vaccines and their effect on the body. Its time these free loaders backed off, the investigation into the corruption surrounding the Big Pharma/CDC/Fauci and Big tech tie up is gaining momentum, if these two clearly very bright creatures don’t want to find themselves in the same situation as Uncle Andrew perhaps they should keep out.

Meanwhile Joe Rogan must be fairly sure he is hovering very close to the target with all these attempts to take him down.

If anyone deserves a medal, for shining a light on Big Pharma and the pandemic fraud and actually getting to the masses in a way MSM never will it is Rogan

He cheated in his art a level the teacher did his crayon picture.

Legendary scientists H & M have expressed concerns. Lots of people have on both sides of the argument. Next.

And in other news “35 year old man beats man 10 years his junior in tennis match lasting over 5 and a half hours” in what was billed as the Australian Open final. Same 35 year old man criticised the world’s best player, who was not permitted to play in the tournament, on solely political grounds, for seeking entry to the tournament while not being vaccinated and has in the past made statements to the effect that everyone has to be vaccinated so that we can get out of the pandemic as it is the only way out.

I very much doubt that someone who had the clot shot – 3 times, if that is the requirement to be “fully vaccinated” – would have been jabbed with the same clot shot he exhorts everyone else to submit to and still be capable of pulling off the feat described in the opening sentence of this post.

I will find it very hard to accept that he is currently the best player of all time, with 21 grand slams to his name, and not place an asterisk beside his 2022 Australian Open [it wasn’t REALLY ‘Open’ was it?], in the absence of seeing a blood sample for independent testing and verification and comparison with A. N Other randomer who DID get 3 clot shots.

And full disclosure, I was formerly a Nadal fan.

Yep, that asterix is indelible.

This is a culture war now. I know whose side I’m on, and it’s not this pair of thick twats!

Hell’s teeth they are awful. Spotify should tell them to just do one. And stop paying them.

Yep, science is now politicised. Kamala says earth is a globe I start thinking it might be flat as a pancake.

I wish these two leeches would P O and mind their own business. Just like our resident trolls on here the best way of dealing with these two horrors is to ignore them; vain, thick and useless.

What the hell would these two know about health matters, particularly vaccines? A lot less than Robert Malone that’s for sure. A sign of weakness when the mainstream narrative has to wheel out has-been ‘slebs’. Another two added to my ‘eff you’ list this last week along with Neil Young. Getting rather long. .Gervais, Lenny Henry, Michael Caine, Elton John, Jim Broadbent….Nearly a hundred now, none of whom know half as much as I do (having researched now for two years) about the toxic product they’re pushing. Drug dealers the lot of ’em.

We need a central compilation for this list. We could call it the “Arya Stark” list.

Lol yes!

Sadly a few of them used to be friends of mine.

I didn’t know Gervais was batting for the jab pushers. I’m shocked. I used to like him for his stance on animal welfare etc. I’m very disappointed in him.

Me too. But there he was enthusing vociferously about getting the jab. To be fair, he wasn’t like that awful Jimmy Carr slagging off ani-Covid jabbers but in his enthusiasm he was very much pushing it.

Shocked? I ain’t. I went to school with that tw*t, not a nice person.

His ‘acting’ isn’t. He’s just playing himself.

There was always a streak of nasty hiding beneath the comedy-gold exterior of Gervais. Not to mention the whiff of hypocrisy. Slags off other celebs for their beliefs, then doesn’t hesitate to inflict his high-school level atheism on us. But yeah, at the end of day, way too chuffed with himself and his cleverness. So comes out as pro-vaxx, what a surprise. Another know-nothing who needs to stay in his lane making amusing television shows and leave the heavy-lifting of epidemiology and medical science to people who actually know something.

These two make me sick to the stomach. I really hope Spotify tell them to do one. Ginger Canute and his talentless harlot.

They are ignorant of just about anything in this world. Whether they were born with a silver spoon in their mouth, or have exploited the grotesque film and TV industry is irrelevant; they are not medically qualified to express an opinion on any medical treatment, tested to death or not.

They have no experience of the day to day privations of people in this country or the US, spouting gibberish as they do from their multi million dollar mansion in Los Angeles. Just go away, look after your children, stop the hypocrisy over flying, shut up and stop seeking publicity for yourselves.

Does this come as any surprise? They’re all part of the globalist elite, trying to protect the narrative.

And Harry openly symbolises his Freemasonry

Not sure about that one. But what do you make of the Merkel quadrilateral which was definitely deliberate?

Can’t believe I used to fancy her when she was on Suits.

I doubt if this couple have even listened to / watched the offending podcast.

Or would understand it if they did.

I struggle to picture a person, who listens to music on Spotify, now sitting up and paying attention with this intervention.

I may as well write a letter in absolute support of Spotify. That’s how much people actually care I would wager.

The next Nobel Peace Prize should go to this dynamic duo, Klaus Schwab or Bill Gates.

I can’t make up my mind which. They’ve all done so much to the world a better place (for them).

They could easily convince us if they told us what was the misinformation they spoke of ?

Have these two actually listened to the programmes they are so offended about? I think not.

They may have listened. But I don’t think it would have been comprehended. There were multiple syllabic words in there.

Am loving Rogan displaying these high level ninja move – by not even commenting.

This gives NutMeg a way out of their Spotify contract. Wasn’t it $18m they received to podcast?

Spotify should just be like “Oh that’s interesting. Would you like us to annul your contract?”

(how many podcasts have they delivered? I think it was 1. Which I haven’t listened to)

If anything or anybody so richly deserved a good torrent of “profanity and abuse”, it’s this Dreadful Duo. However, mindful of the enjoinder in place here, I shall be a good chap and keep my own counsel.

Yep: but don’t worry – we all know how to read between the lines!

So sick of these ‘elites’ sticking their noses in everything. They should mind their own business.

I’d say this qualifies as a strong vindication of everything Rogan and his ‘misinforming’ guests like Malone ever said.

This is what a proper liberal and journalist just wrote about misinformation, censorship and unenlightened and unconstitutionally behaving people like those 2.

https://www.zerohedge.com/political/greenwald-pressure-campaign-remove-joe-rogan-spotify-reveals-liberal-religion-censorship

Also, no wonder that they are Boomer kids and Millennials, certainly intellectually.

https://amgreatness.com/2022/01/29/the-road-to-vengeance/

https://amgreatness.com/2022/01/27/the-needle-and-the-damage-done/

Harry is such a lazy and revolting little cnt.

He was funny once, even wore the family uniform.

I understand that one of the reasons the Queen hasn’t stood down for Charles is that there are a number of countries (like Australia and New Zealand) who will drop the UK and the Commonwealth once the Queen dies or steps down.

Well, on that (if little else) I am on the NZ/Oz side. Could we not just drop Charlie-boy and Willie and just skip to a different Royal family: how about Farage?

At the end of the day, the only reason we have a monarchy is that centuries ago, some hard bastard made himself ‘King.’ Therefore, the whole idea of a monarchy is terribly outdated.

We must all wonder how Spotify could possibly go against the advice of two such towering intellects (a C-list actress and a B-list royal). I suppose one could argue that they are experts when it comes to misinformation (and that’s a polite word for what they spout).

You can almost smell their desperation to stay relevant.

More likely the bleach 🙂

I just realised that her b-hole is most likely bleached.

The rest of her is….

As the narrative starts to look shaky, those pushing it are becoming more desperate. Rogan frightens them because he is hard to cancel.

The DT lies by omission by leaving out the touched couple’s multi million $$ deal with Spotify /Netflix…..

Wonder why that is.

They will be invited to join SAGE very soon. Sad isn’t it that until now we have been totally unaware of their scientific accomplishments?

Some say he’s not the spawn of Charles but he’s definitely the product of Charle’s eco-woke-twattery.

The list of utterly insignificant and irrelevant B listers on the wrong side of history grows almost by the hour!

It’s been a hilarious episode in an otherwise tragic period of history.

Now if they’re expecting me to comment on the ‘Sussexes’ without profanity and abuse they can fuck right off

Well said what a pair of c***s

LMFAO !!

Working a rare Nursing shift as I write.Five Residents are positive for the Black Death not symptomatic and stabbed thricely.I ask the care staff the obvious I’ve seen more sentient looks from cattle for fucks sake!!!!!!

Look on the bright side – it’s confirmation of the intelligence and veracity of Malone etc.

‘Rogan himself has said on his show that the young and healthy do not “need” the vaccine. He later clarified that he was not anti-vaccine and stated: “I’m not a respected source of information.”

Last year he outlined his position on the vaccine, saying that he was “not an anti-vax person” and adding: “I believe they’re safe and encourage many people to take them’

maybe they’re calling him out for spreading misinformation about him saying the vaccine is safe and encouraging others to get it.

I don’t know what “Spotify” is, but if you own a media company in Beverly Hills as those two do and its “personality” has a big streak of propriety and rectitude, as surely their company’s does, then presumably you gotta keep the Big Pharma mafia sweet as well as the Scientologists and the MPAA.

Let’s all express ‘concerns’ about Ginger & Whinger, then maybe Spotify will censor them instead.

Bet they’ll never ask Andrew to babysit.

That’s very good.

As if they would ever give a fuck about their kids, Mick Philpot would do a better job until benefits were taken away and he ovened them.

These two. What a pair of irrelevant plonkers. Their press statements are always so hilariously over the top, as if they are written by 9 year old girls.

It’s delightful that Neil Young (is Toby by any chance related?), Joni Mitchell & now the noisome duo have done more to publicise Rogan that could have been imagined.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streisand_effect

My name is Prick Harry… my dad said so….

It’s be even more clear if you added in a third photo of Charles’ grotesque homozygous mugshot.

Di was a right slag bless her

Oh dear.

Whoops!

Speaking on behalf of the nation – Those two ***** can f*** off.

Megan: “Harry, oh Harry… why is everyone talking about Neil and Joni, they should be talking about us…”

Harry: “I’ll them to drop Rogan or we won’t make another podcast.”

When did they sign the contract with Spotify? What was the output/deal supposed to be? Is the company in breach of contract with Spotify? Are they looking for a way out and seeing the Rogan issue as a means to deflect?

So many questions, why doesn’t somebody from the entertainment press ask them?

I wager Rogan was not given freedom by Spotify to interview whoever he wants, there will have been a small list of verboten names included in that $100M contract, and David Icke will have been at the top of that list.

Icke on JRE would cause a censorship meltdown.

They’re only ever allowed to be photographed from the waist up, so you can’t see the leash and collar Megan keeps around Harry’s scrotum.

“Hundreds of millions of people are affected every day by the serious harm of mis and disinformation.”

They’re right about that…. just dead wrong about the source.

They’re just saying “we’re still here”

Blimey these two take the biscuit. Who cares what they think. I used to admire royals but no more.

They’re not royal anymore.

I am not surprised these totalitarians would make a moronic intervention on this subject.

Notice they have only expressed concerns. That costs zero dollars. Spotify’s contract with Rogan is reported to be mostly on Rogan’s terms. If Spotify breaks the contract and demands censorship rights, Rogan will own Spotify.

James Hewitt’s son doesn’t have a single GCSE to his name. He is so stupid, and so dispensable that they sent him to Afghanistan. He then married a coercive controlling liar. I wasn’t planning on taking a vaccine that doesn’t work; after their intervention I am even less inclined.

All this prominent people openly calling for censorship because they’re so convinced that wrongthink must be suppressed are a real disgrace.

This seems to be a reputable report of genuine findings of nanotech in some of the vaxxes. Two responsible and intelligent people not afraid to risk being derided for their findings.

https://odysee.com/@spearhead4truth:e/Nanotech-discovery-280122:9

Nanotech found in Pfizer jab by New Zealand lab. Sue Grey Co-leader of Outdoors and Freedom Party and Dr Matt Shelton report findings to Parliament’s Health Select Committee.

http://www.orwell.city has been publishing similar work from Spain, since last year, as have German pathologists.

That’s weird, isn’t Sue Grey the one supposedly investigating partygate?

She’s a woman of many talents. I hope she’s put this in her Partygate report.

This open letter suggests to me that the “other side” are not backing down on their programme of vaxxination.

Despite the rebellion in Canada, I think the “other side” will have wargamed this, and will not give up.

Reads like a threat.

https://noorchashm.medium.com/an-open-letter-to-drs-3e5e1bffd404

An Open Letter To Drs. Peter McCollough, Robert Malone and Pierre Kory — On Your Public Disparagement of COVID-19 Vaccines And Marketing Of “Early Treatment” To Infected Americans.

In this open letter to Drs. McCollough, Malone and Kory on the public record, I point to a very serious, and likely dangerous, error being committed by their disparagement of COVID-19 vaccination and marketing of a specific and systematized “early treatment” algorithm ….. Certainly, I have very serious concerns about the legality of their professional scheme.

Drs. McCollough, Malone and Kory,

I am compelled to write you this public letter of critique and professional opinion as a physician-immunologist, a public health advocate and an American citizen — having carefully listened to your perspectives and watched your public displays in the press and on the internet for the past 2 years. Specifically, after observing you on January 22 and 23, 2022 at the press conference organized by Senator Ron Johnson— there is no choice left, but to express my very serious concerns to you and to the American public.

BLACK TRASH

Niggardly naggers gotta nag, like a niggard.

Joe Rogan said his doctor, Pierre Kory, is part of a group that has used Ivermectin to quietly treat 200 Members of U.S. Congress for COVID19. Dr Simone Gold, from America’s Frontline Doctors, told that she has prescribed treatments for Congress. She still believes in her oath, but she is vocal saying she has been contacted by many in DC. Can you believe these demons? Healing for them are OK but not for us. Get your Ivermectin while you still can! https://ivmpharmacy.com

A neighbour’s dog crapped on my front lawn.

Over to you, Mrs and Mr Markle.

I quit Facebook around 5 years ago when I got sick of justifying my existence on such a politically charged intrusion into my life. I’m now in the process of removing all my information off the Google platform for the same reason.

Like everything when you become Blackpilled (and I’m not talking about the laughable faux black-pill James Delingpole claims to have taken), it’s not an easy task ‘releasing’ yourself from the shackles that lock us into this false reality.

And I’m minded of this while watching the fake battle going on between Rogan and the entitled fruity commie celebrities, whose job it is to look like they’re fighting the good fight.

You might think Rogan is a good guy, and he probably is to some extent, but real opposition would have been strangled of support long before they got as many followers as Rogan.

A viral infection that kills roughly 0.15% of those who contract it and still the madness persists.

WTF has happened to Homo Sapiens?

Please, everybody, get a grip.

Now those 2 narcissistic airheads have given us their truth Spotify must be sooooo scared 🤣🤣🤣

Am I right in thinking there’s a touch of hypocrisy about Neil Young … Back in the 60s he was one of the first to complain about censorship , at the time of Vietnam, Kent State etc …

hH and M are merely jumping on a bandwagon, not surprising, no one is the slightest bit interested in them ….

They are just a gift that keeps on giving- they provide a reverse moral compass for us all- if they say it’s true, we know it’s not. They should market this as another one of their products.

Is there a bandwagon anywhere that this pair won’t jump on?

So far, the answer is ‘No’.

Happily even the vaxxed are seeing the reality. The highly vaxxed countries also have the most covid cases. No offence to Meghan and Harry, but I prefer to take my medical advice from a person who has attended medical school. People like Drs, Ioannidis, Battacharya, Malhotra, Kory, McCullough, Atlas, and thousands of other doctors witnessing the reality.

The point is, this another warning that people with lives of privilege, money and power, celebrities or polticians or otherwise are going to keep on turning the screw on the rest of us.

Censoring us, controlling us, squashing our freedoms and rights and impoverishing us while enriching themselves to the max.

This, along with challenging the eco loonacy, is the biggest fight of our lives.

And that fight back needs to start now.

There is a lot of misinformation [sic] about his!

A senior advisor at The Blackstone Group is an ex-CEO of Pfizer.

Blackstone owns half of Hipgnosis.

Hipgnosis owns Young’s music.

Young’s music is on Spotify.

Spotify allows free speech including anti-narrative opinions on, er, Pfizer’s jabs.

Me? I can’t see a connection at all.

Thick as mince former royal and 3rd rate actress give us their views on experimental gene therapies……. yawn.

Time for a heated debate between Prince William and Dr. Robert Malone. I’d watch that – my money’s on…err…oh it’s difficult to predict who’d win.

We need a trigger warning for any article referring to this pair of pariahs!

Another reason to stop worshiping the Saxe Coburg Gotha family like many unfortunately still do. The idea of a god appointed family to rule over a nation has had its day – if the Royals weren’t senior Freemasons we would have moved on. It’s just the thought of Emperor Blair or similar that gives people pause to thought.

They are just preparing us for some type of international ‘misinformation’ law, so they can get away with a full on police state and genocide next time.

Another reason to ditch the monarchy.

This is a fantastic opportunity for Harry to show the world what the best education and all the money in the world can buy. OK Harry, please make an online presentation detailing exactly how these injections work, what the mechanisms of so called protection are, and why it is essential for perfecty healthy people with no theoretical risk from Convid – because in the under 70s the original super deadly strain (never isolated or proven to exist so Harry can enlighten us as to the rigorous irrefutable proof that this is all underpinned by legit science) had a survival rate of 99.97 percent so trying to improve upon that is barking mad for a start. So please, Harry, put your money where your mouth is, make a presentation outlining your case, and well critique it. We will ascertain if you are speaking sense and truth, or if you are just shilling for the forces of evil who are running this blatant scam.

Here is one John Ioannidis paper confirming the exceptionally low mortality rate of this super killer mega virus which shut the world down. This can be Harrys starting point for his presentation – why healthy folk should be injected with experimental gene therapy which has an unbroken history of failure in animal trials – ditto coronavirus vaccines which have never gone beyond animal trials, and including the Convid injections which are killing and maiming on an unprecedented scale. Were all ears Harry.

Global perspective of COVID-19 epidemiology for a full-cycle pandemic

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/eci.13423

I watched Jimmy Dore an American Comedian at 5am this morning. He had Dr Bhattachariya and Dr Kuldorff on. I bet that will annoy the same people although Jimmy has less followers he still gets a lot of views. He has had problems since getting the vaccine and is in a study group of people with who suffered adverse reactions. One of the medications he has been given is ivermectin.

Yes all these “celebrities who know F.A about medical matters. Is it because it gets them in the news or because they are getting paid.

Back in the 1970s a tv company announced it was going to make an in-depth, heavily-researched programme on the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and to do this advertised widely throughout the world foer anyone who had ever met and/or had dealings of any kind with the couple. Whoever replied, and there were reported to be approaching many thousands replying, were sent a questionnaire to be filled in. One question was “In the course of your meeting/dealing with the couple, either singly or together, did the couple pay for any meal or refreshment enjoyed at the time?

in all the thousands of replies, not one said the Windsor’s picked up the bill. I have no doubt that it is a similar case with Ginge and Minge.