Lockdown proponents often argue that, although case numbers sometimes decline in the absence of a lockdown (as in Sweden, South Dakota, Florida), case numbers always decline in the presence of one. Once you put a lockdown in place, they claim, the curve reaches its peak and the epidemic starts to retreat.

There are certainly many countries where a decline in case numbers has coincided with the imposition of a lockdown. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that one caused the other.

As the researcher Philippe Lemoine has argued, people start changing their behaviour voluntarily when they see deaths and hospitalisations rising. The government, meanwhile, feels an increasing need to “do something”, and the subsequent imposition of a lockdown happens to coincide with the peak of the infection curve.

Consistent with this account, there are several countries where a lockdown was imposed, but case numbers did not immediately decline; or if they did decline, they rose again while the lockdown was still in place. These examples constitute evidence against the claim that lockdowns have a substantial effect on the epidemic’s trajectory. Here I will present six.

It’s important to note that some countries went into lockdown all at once, whereas others built up restrictions gradually over several weeks. This raises the question of exactly how to define a lockdown. For the purpose of this analysis, I will rely on the Oxford Blavatnik School’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.

The dataset includes several measures of government restrictions. Each one is accompanied by a “flag” indicating whether the relevant restriction was applied to specific regions or the entire country. I will define the start of a lockdown as the first day on which there were mandatory workplace closures and a mandatory stay-at-home order in place for the entire country.

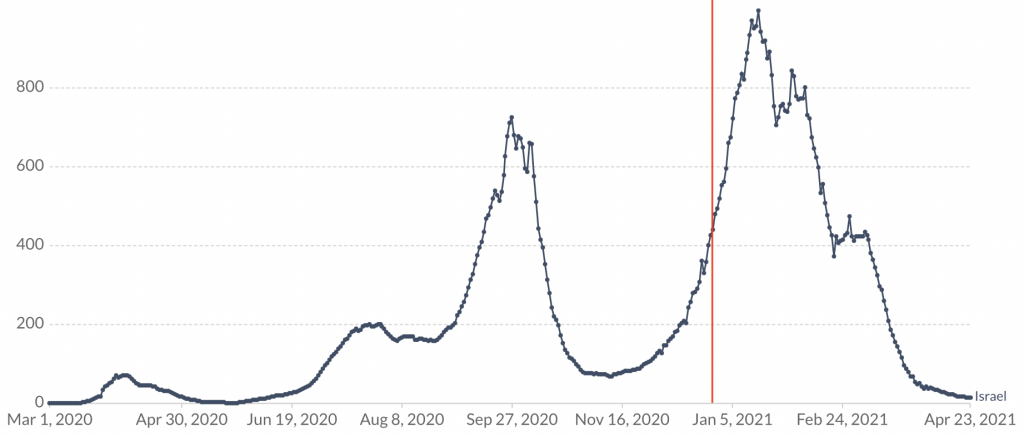

The first example is Israel, which went into lockdown on December 27th, but did not see the peak of its infection curve until January 17th.

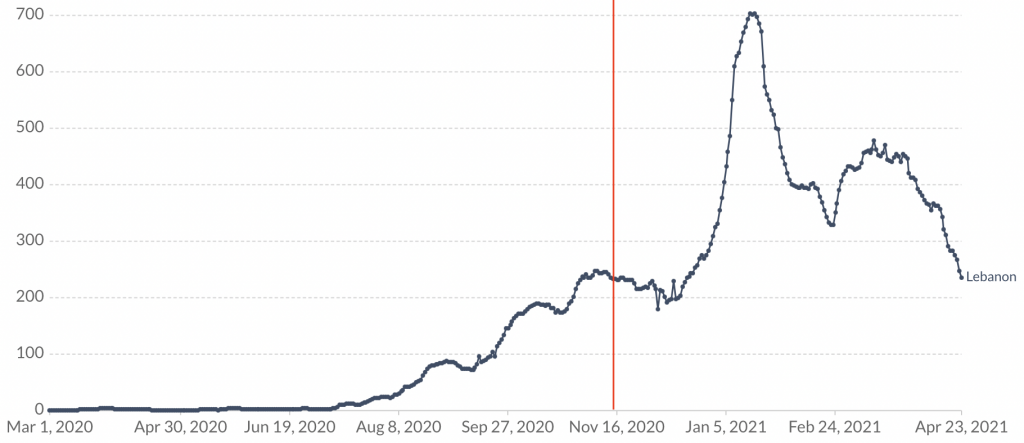

The second example is Lebanon, which went into lockdown on November 14th, but did not see the peak of the curve until January 16th.

The third example is Slovakia, which went into lockdown on October 22nd, but did not see the peak of the curve until January 6th.

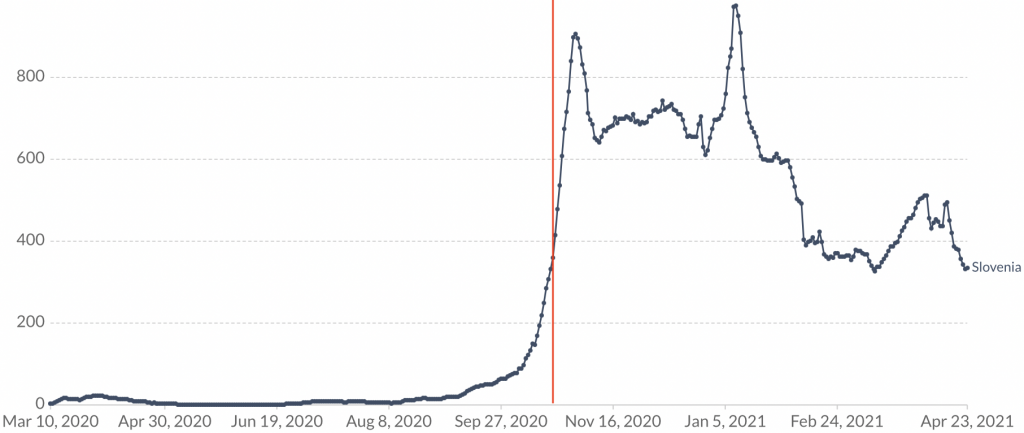

The fourth example is Slovenia, which went into lockdown on October 20th, but did not see the peak of the curve until January 10th.

The fifth example is Peru, which went into lockdown on March 16th, but did not see the peak of the curve until June 2nd.

The sixth example is Venezuela, which went into lockdown on September 28th, but did not see the peak of the curve until April 6th.

Note that, in every case, the lockdown measures were in place until after the peak of the curve. The fact that cases did not immediately decline, or proceeded to rise again (as in Venezuela), cannot therefore be blamed on the lifting of lockdown measures.

The evidence presented here is consistent with the many empirical studies finding that lockdowns do not substantially reduce deaths from COVID-19.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

‘Case’ numbers. Not hard data.

No more needed to be said for me to stop reading and just have a quick look at the graphs of what we already knew.

Although this is an important argument, as per the brilliant John Tamny (“When Politicians Panicked”), it is not the main argument.

Lock-downs of the healthy are never justified, and the deadlier the virus the less justification there is for them: “the more lethal the virus is presumed to be, the less need for rules and laws in a vain attempt to force behavior. When it comes to illness and potential death, people don’t require force. At all.”

whatever happened to SARS-COV-1?

did we all get it asymptomatically or did it just disappear?

Why has nobody has ever asked that simple question on the tele?

Because tele doesn’t do questions :-). It just does scripts.

I don’t really know the answer but I am interested in how viruses ‘crowd each other out’. Or how you can’t get covid if you’ve got a normal cold etc.

I expect something crowded out sars-cov-1 – possibly something without symptoms. Or maybe its just one of the 200 colds out there we don’t bother testing for. or a less dangerous mutation came along and crowded itself out.

I expect sars-cov-2 will do the same. unfortunately the boffins who do the modelling for us haven’t worked out its seasonal and they expect everyone in the world to get it (unlike every other disease ever).

my betting is it won’t come back now we have had 1 full season. there isn’t a person in the UK that hasn’t been exposed – I expects fragments of it are in every breath you take. ‘glancing blows’ as Heneghan puts it.

of course we will probably be locked down again this winter as flu comes surging back and apparently the only ‘weapon’ in our armoury is house arrest

Also missing from most of these “models” is the almost certain fact that the virus WAS spreading – and spreading “widely” – months before the lockdowns began (or the “first” cases were reported in Wuhan). If the virus WAS spreading in November of 2019 (probably earlier), then it’s now been circulating for at least 17 months. How long did the Spanish flu last?

I read where the health experts in Switzerland now estimate “conservatively” that 33 percent of its population has, by now, been exposed to the virus. But, presumably, these experts began their counting around late February 2020. What if they counted everyone who had contracted the virus beginning in November 2019? They’d have completely different math and calculations.

This government also bases its “prevalence” estimates on antibody test results of the population. Per the studies I’m inclined to believe, detectable antibodies begin to disappear in “most” people within a few months … so these antibody tests would “miss” people who had the virus four, five, six, seven months, etc. before these people got an antibody test.

yes. I don’t expect you’d bother making antibodies if you got covid very mildly

That seems to be true – how long the antibodies last also seems to have a great deal to do with how much “viral load” you had, or how severe (or mild) your particular case was. And most people are either asymptomatic or have only very mild symptoms. All of which tells me that the “undercount” of past “cases” is far greater than even most of the experts say.

Agree completely. Harvey Risch of Harvard believes herd immunity has been reached in most US states, especially those which didn’t lockdown or lifted early.

Mike, have you reviewed the PCR test details for SARS and compared them to Covid-19? See my post above discussing how SARS PCR test guidelines were for 25-30 CT rather than the stratospheric 40-45 used for Covid-19.

It more than likely spread round the world as a cold. No panic – no issues.

Any excess deaths put down to flu or “mystery virus” as usual

Would account for the high level of pre existing immunity (along with the other Hcovs

I did some digging recently and it turns out that SARS testing was dramatically different, with PCR cycle threshold set at 25-30 rather than the 40-45 used in US and EU for Covid-19. This is a dramatic difference b/c of the 3x amplification with each cycle. What this means is that SARS testing avoided the massive numbers of false positives we’ve seen with Covid-19. A second major difference is that SARS tests were only done on symptomatic patients, avoiding an additional source of false positives. No significant numbers of SARS cases were reported after 2003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14699465/

When I draw the curtains, has zero impact on when the sunsets.

Nice one.

And “… if you break the bloody glass you won’t hold up the weather.”

There is nothing new to write about if you aren’t in earnest search of the truth.

Any thoughts on China?

They have almost no cases these days. What gives?

Is their testing different?

Does the virus have a more limited impact on people of ‘Chinese’ origin?

Do they have medication that can deal with the virus that we dont use?

It would be interesting to know what is going on here.

“It would be interesting to know what is going on here.” It would be interesting to know what’s going on anywhere, but most govts are profoundly uninterested in reality, only in spin. Anyone who simultaneously believes our stats and China’s must have a great capacity for cognitive dissonance, but the lockdown zealots have to go along with it – “China has fewer cases because they locked down harder and better”. Yes, they stopped it spreading to the rest of China but not the rest of the world. Madness.

Must be a shortage of journalists because all the obvious sceptical questions go unasked.

Not a shortage; they’ve all been bought. Gates/Soros et al have bought up just about everyone. Very few have resisted. Even people like Charles Moore – reliable stalwart in the past – suddenly changed his tune. Plenty of journos around – just not doing their jobs.

Any investigative journalism in the main stream media died a long time ago. They’ve all been bought off, which is how the government and their handlers have been able to control us. Such compliance could not have been achieved without their collaboration.

Exactly, how else do you explain a virtual news blackout of last Saturday’s massively-attended anti-lockdown demo in London. News blackouts are generally the tools used by totalitarian states.

I seem to remember they take intravenous vitamin C more seriously than we do. I remember a piece of advice somewhere, to give children 1,000mg of vitamin C per day for each year of their life so far, up to 10,000 mg at age 10, the peak amount to be maintained thereafter. The person who tried this said his children were never ill.

I mostly make do with 3,000mg, still, I haven’t been off work sick for years.

I haven’t seen any serological studie from China. These have been absent.You would think it would be of extreme interest also if they had C-19 before and tested saved sera.But obvously no interest in that subject from China and revealing no interest from investgative journalists in MSM either.

To be honest you cannot believe anything China has to say.

Take the statement of lockdown fanatics with a pinch of salt, they need to know about seasoning.

The 7th and most prominent is Greece.They have a non stop lockdown since November and a strict lockdown for the whole of March. Cases and deaths sky rocketed during the lockdown period.

I live in Alabama 2 1/2 hours north of Florida. In my state, cases, hospitalizations and deaths have all been higher than our southern neighbor on a per capita basis. And our state had “lockdowns” beginning in March 2020 and only ceased our mandatory mask requirements 10 days ago. Shouldn’t Florida have been a mass casualty state compared to my state? And the percentage of the population in Florida that is 65 and older is far higher than my state (or any state for that matter) … Yes, the argument that lockdowns and masks “save lives” is as spurious a conclusion as one can find.

How polite you are, Bill :-). I think the short version is ‘lie’.

I live in Greece and the country went into a hard lockdown on 7th November and we are still locked down. Deaths dropped to about 20 per day from about mid December but our PM kept us locked down. Since early February cases and deaths have increased and are still about 80 per day. Not many compared to other countries but comprehensive proof lockdowns do not work as after nearly 6 months of lockdown deaths are higher than when we started. Very slowly businesses are starting to open with cafes, bars and restaurants opening from Monday. Some freedom at last

2 points to note:

It’s simply not about what works, is it?

‘ case numbers ‘ here we go again not reading the rest either