A new study has appeared that shows once more that lockdowns have no discernible effect on COVID-19 infections or deaths, despite their colossal costs and harms.

Maria Krylova, writing in the Canadian publication C2C Journal, looks in detail at two pairs of similar US states that implemented contrasting measures in response to the pandemic to see if there were significant differences when it came to Covid infections and deaths.

She explains that her research is motivated by a wish to see rational cost-benefit assessments of policies responding to pandemics.

While aimed at fighting the virus’s spread, the interventions imposed a massive toll in areas including global hunger, domestic abuse, mental and physical health problems, suicides and bankruptcies. Despite these grim consequences and, more recently, the accelerating pace of vaccinations and the gratifying reduction in deaths from COVID-19, many North American governments remain reluctant to ease the restrictions. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mused lately that the Canada-US land border would reopen “eventually”, while some public health figures are now calling for a third lockdown.

Before we – again – do anything that drastic, we need to pose an important question: Did the lockdowns actually work? Not merely in the sense of keeping people at home and convinced that their governments were doing something; but in actually altering the course of the virus through the population. This should be a crucial matter of interest to every citizen and politician. It is key to rationally assessing the costs and benefits of imposing similar social and economic policies during the next serious epidemic.

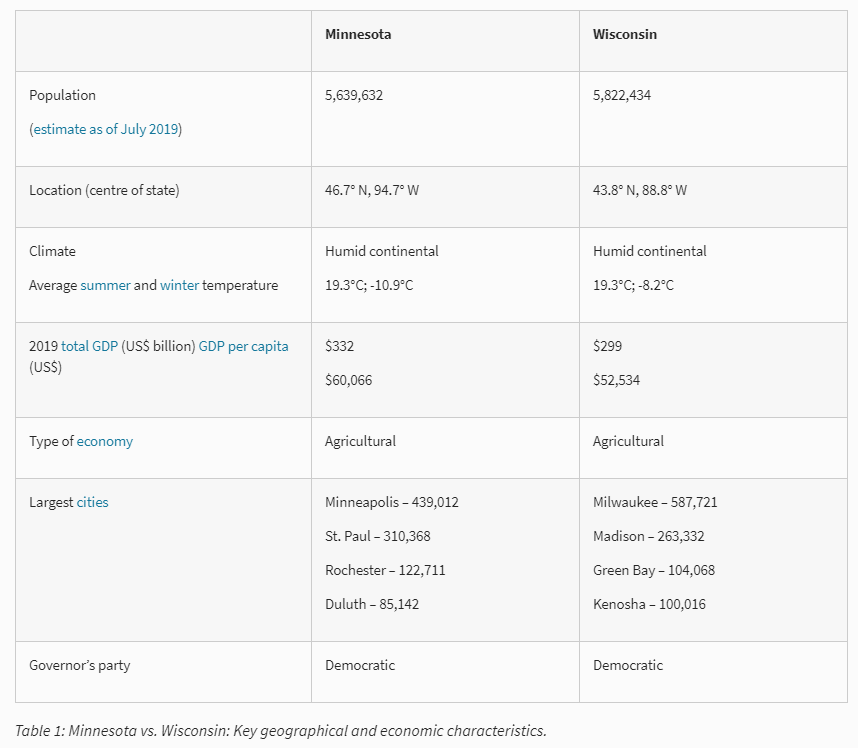

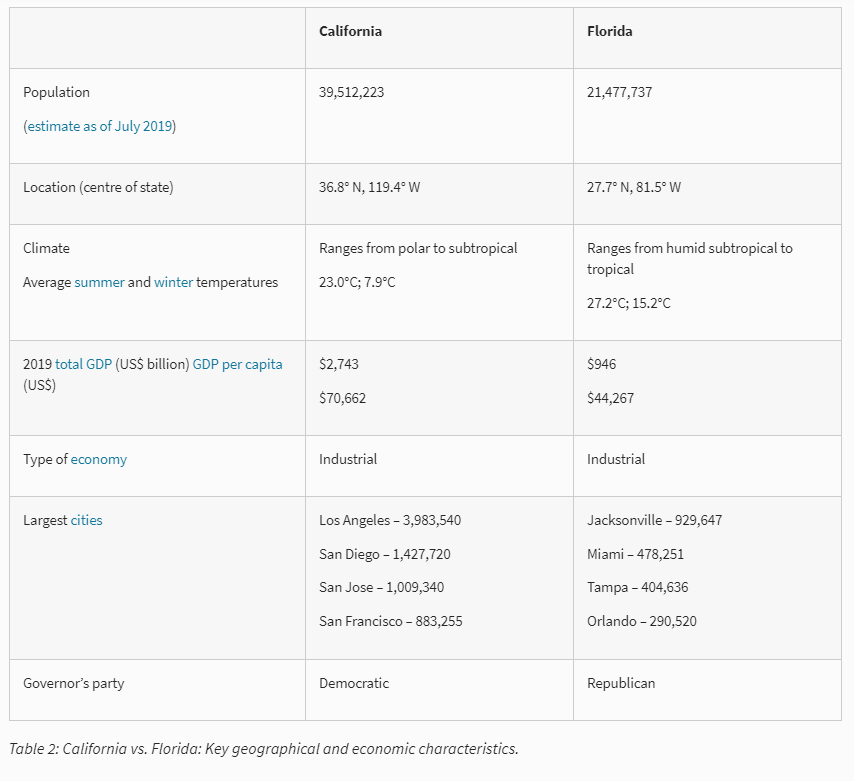

She has gathered a wealth of information on the four states in question.

COVID-19-related state-level regulations and measures were gathered and examined in their temporal relationship to the pandemic’s development, reflected in the case and death statistics (daily and total) in two pairs of U.S. states. Each pair of states is broadly comparable in climate, population, urbanization and economic characteristics, but is contrasted in the degree of severity of its statewide rules.

Two are mid-sized, adjoining Midwest states: Minnesota and Wisconsin. Minnesota had a hard and extended lockdown (many schools are still not open, for example), while Wisconsin had a short lockdown followed by moderate restrictions. The other two are southerly coastal states – California and Florida. California has had a hard and ongoing lockdown, while Florida has sought every opportunity to ease restrictions and reopen. Two other seemingly suitable cases were omitted: New York, a hard-lockdown state, because of its unique circumstances (including heavy mass-transit use in its largest city, and its deadly nursing home scandal), and South Dakota, North America’s only jurisdiction to remain fully open throughout the pandemic, because of its small and non-urbanized population.

There is an array of uncontrollable or unmeasurable variables related to the pandemic’s course, the public health response, the political response and the nature of the studied states that further complicates state-by-state comparison, increases uncertainty and, hence, lowers the confidence of conclusions. The process requires making a number of important assumptions. Among these are the accuracy of COVID-19 testing, the accuracy of case and fatality counts, and the state-to-state and temporal consistency of lockdown enforcement. The key assumptions are discussed in the Appendix.

Because the pandemic is ongoing, the observed trends are accurate to mid-March 2021. There is no intention to forecast the pandemic’s future course.

Here’s her comparison of Minnesota and Wisconsin.

She gives a detailed timeline of the measures each state implemented, before summarising them, noting Minnesota imposed much stronger restrictions than Wisconsin.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Minnesota imposed stay-at-home orders for 54 days, social gathering restrictions for nearly 300 days, severe social and business restrictions for 29 days and school closure from March 15th, 2020 through the end of that academic year, with only kindergarten through grade 2 reopening in September. A complete return to in-person learning was not authorised by the state until mid-January.

In contrast, at a state level Wisconsin implemented a stay-at-home order for 28 days and social and business restrictions to various degrees for 61 days. The strictest order on social gatherings (akin to stay-at-home rules) lasted for 31 days. Similar to Minnesota, Wisconsin’s schools were closed from March 13th until the end of the academic year. Since September, local authorities have been authorised to choose between virtual and in-person learning for all grades; the Legislature’s state budget committee plan of February 10th intends to penalise schools that continue to stay closed by limiting funding.

Altogether, throughout the past year Walz has issued 112 executive orders related to COVID-19, while Evers’ cabinet issued 46 orders. As noted above, Evers’ authority to impose statewide measures was limited by the Republican Legislature majority following the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s ruling of May 2020.

She also compares California and Florida.

California, she explains, has had much stricter measures than Florida.

Overall, California experienced the severest statewide restrictions, staying in lockdown for 51 days, in near-lockdown for over 120 days and under nighttime curfew for approximately 75 days. Less restrictive rules lasted for about 50 days in total. Schools have not been open consistently in the new year given the state’s shift to the strictest restrictions in November and December.

Florida’s state-at-home rules lasted for less than one month, its definition of “essential” activities was the broadest, and the state has been continuously opening up since late April 2020, although some cities and counties have resisted state policies.

Altogether, Newsom issued 92 COVID-19-related executive orders, in contrast to DeSantis who signed 42 orders. By mid-March 2021, a drive to trigger a recall election of Newsom had generated 2.1 million signatures.

She takes a detailed look at the relationship between a state’s restrictions and its COVID-19 cases and deaths data. Summarising, she notes the lack of obvious impact from any of the measures.

1. The stay-at-home orders, which varied greatly in intensity and duration (and, anecdotally, in enforcement severity) seem to have made no observable tangible impact on the daily COVID-19 cases and deaths. Further, the most severe restrictions, such as a prolonged lockdown and nighttime curfew implemented in California in November, did not prevent the subsequent December-January spike in cases or fatalities.

2. Following imposition of statewide mask mandates, there was no observable change in the daily infections or deaths in Minnesota, California or Wisconsin, nor in Florida, which never imposed this regulation statewide.

3. In contrast to the three other states, Florida experienced two distinct COVID-19 waves, while its daily COVID-19 cases and deaths grew less sharply during its cooler season and were distributed more evenly throughout the year. But does this trajectory translate into greater infection and/or death rates in Florida than in California or the other states? A review of the general statistics on COVID-19 cases and deaths might help answer this question.

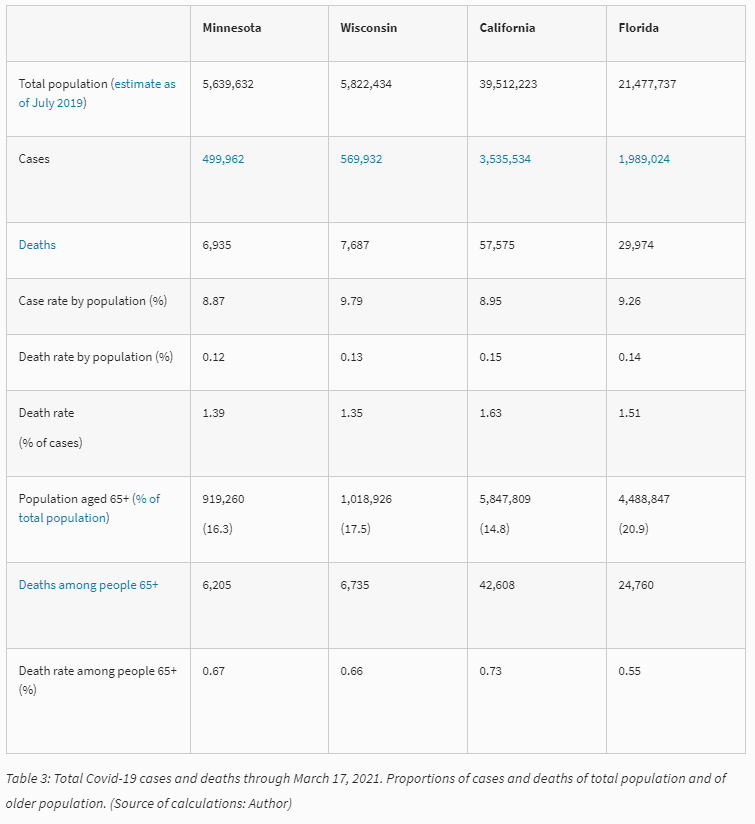

Here’s her table summarising the four states’ Covid statistics, with no obvious benefits from strict lockdowns.

In conclusion, she notes that the two states with the least restrictions had the lowest death rates for the over-65s, among other things.

– Despite restrictions of differing severity and duration, there is little difference in the total number of COVID-19 infections and deaths across the four states, respectively, averaging around 9.22% and 0.14% of each state’s total population. The fatality rate is also comparable, although it is somewhat greater in California and Florida than in Minnesota and Wisconsin. This difference does not seem to be related to the regulations that were imposed.

– Regardless of the state-by-state restrictions, the percentage of deaths of people 65 and older is under 1% in each of the four states, with Florida having the lowest rate. As well, the two least-restricted states had the two lowest death rates in this category.

– Regarding the original rationale for imposing lockdowns – to “flatten the curve” – the least restricted state, Florida, experienced an overall rate of cases and deaths comparable to the other three states. Paradoxically, Florida’s double-hump pandemic also forms the flattest trajectory of the four states. Whatever policy choices Florida’s government made, or whatever luck the state benefited from, the least-restricted state, with the highest proportion of elderly, had arguably the greatest success in preventing the overwhelming of its hospitals as well as limiting deaths among its most vulnerable age group.

Unfortunately, towards the end she hypothesises that voluntary social distancing (as opposed to enforced lockdowns) is what really makes the difference in terms of reducing Covid infection rates and deaths. This claim is contradicted by a number of studies, including a recent one in Nature, reported in Lockdown Sceptics, which did a pairwise analysis of 87 regions around the world and found only 1.6% of pairwise comparisons showed an association between reduced mobility (staying at home) and lower Covid mortality. The problem for sceptics in affirming the effectiveness of voluntary social distancing is that it suggests that there may be a flood of Covid deaths only being held back by keeping social distancing in place. This won’t help arguments for reopening (though the vaccines may help overcome that problem).

The C2C Journal study is definitely worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Activist groups will now wield the power to complain on behalf of others”

I wonder how much success a conservative/right wing/non woke “activist group” would have in complaining on behalf of, for example, a lockdown sceptic who had been accused of being a granny killer for not following rules, being an anti-vaxxer etc.

Clarkson, I believe, made the fatal error of issuing a grovelling apology to the MMthus playing right into the hands of the activists. Presumably his fear of being cancelled trumped upholding principle.

This may both encourage activist groups to continue lodging//pursuing complaints to IPSO and emboldens the politicised IPSO to arrive at their ruling of upholding the complaint.

Piers Morgan did at least refuse to apologise to MM.

Never apologise, never explain.

IPSO effectively supported the COVID narrative. They are not independent.

yes I made several complaints to IPSO that the disgraceful series of articles in the MSM in early 2022 reminiscent of how things started in Germany that those refusing the jab were idiots, unclean,should not be allowed in hospitals, on public transport, made to suffer etc; offended the code as being discriminatory,harassing and inaccurate. IPSO rejected all complaints which it justified on the basis of a very strict legalistic interpretation of its rules

The veneer of civilization is waffer thin and is peeling away faster than a ginger with sunburn.

Oi..!

https://www.farminguk.com/news/natural-england-gives-sssi-status-to-penwith-moors-amid-farmer-concern_62886.html

A very worrying development. Land which has been effectively managed by local farmers for centuries will now be “locked up.” The attacks on farms and farmers will definitely intensify.

Interesting that the area is of value to wildlife after thousands of years of farmers managing it, so their solution is to stop the farmers managing it? A very similar thing is happening in Western Australia. Under the guise of protecting Aboriginal Cultural Heritage new legislation was passed which requires anyone who owns land greater than 1100 square meters to seek an assessment and approval prior to undertaking any disturbance in case they disturb potential cultural heritage sites.

Good points. Thanks.

Ipso, the press regulator…

I am absolutely fed up to the back teeth with ‘regulators’…

Regulators curtailing free speech, regulators facilitating the promotion of highly questionable medical products such as the Covid vaccines…

We’re awash with ‘regulation’ which is not working for the people.

Whose best interests are being served by this overbearing regulation?

I do not consent!

Hear, hear.

The only interests served are those of the serially incompetent who can’t get a job in the commercial world so end up as a ‘regulator’ sticking their noses in others’ business.

I see that the Financial Times, The Independent and The Guardian have opted out of IPSO. Perhaps it’s time the other papers did too.

I believe the chances of Jeremy Clarkson writing for any of the above publications is on the far side of remote.

True. But irrelevant!

Actually it is not irrelevant as it very neatly points out the bias of the named publications and of IPSOS.

above I have referred to my complaints being rejected by IPSO. At least I was able to complain about articles inTelegraph, Mirror, Express and Mail but I remeber could not do so for one in Evening Standard as not a member. So despite all its faults I am even more suspicious of those papers who are not members of IPSO.

Agreed. The use of the expression “going forward” at the end of the second sentence is incomprehensible, however.