As we pass through the anniversary of the week in which our freedoms became circumscribed by the outputs of a physicist’s dodgy computer model, Phillip W. Magness at AIER has revisited Imperial’s infamous Report 9 to remind us quite how wrong it was.

Ferguson’s model presented a range of scenarios under increasingly restrictive nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Under its “worst case” or “do nothing” model, 2.2 million Americans would die, as would 510,000 people in Great Britain, with the peak daily death rate hitting somewhere around late May or June. At the same time, the ICL team promised salvation from the coronavirus if only governments would listen to and adopt its technocratic recommendations. Time was of the essence to act, so President Donald Trump and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson both listened. And so began the first year of “two weeks to flatten the curve”.

It took a little over a month before we saw conclusive evidence that something was greatly amiss with the ICL model’s underlying assumptions. A team of researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden adapted Ferguson’s work to their country and ran the projections, getting similarly catastrophic results. Over 90,000 people would die by summer from Covid-19 if Sweden did not enter immediate lockdown. Sweden never locked down though. By May it was clear that the Uppsala adaptation of ICL’s model was off by an order of magnitude. A year later, Sweden has fared no worse than the average European lockdown country, and significantly better than the UK, which acted on Ferguson’s advice.

Pressed on this unexpected result, ICL tried to distance itself from the Swedish adaptation of its model in May. The records from the March 21st supercomputer run of the Uppsala team’s projections belie that assertion, linking directly to Ferguson’s March 16th report as the framework for its modelling design. But no matter – the ICL team’s own publications would soon succumb to a real-time testing against actual data.

A second ICL report, attempting to model the reopening of the United States from lockdowns, wildly exaggerated the death tolls that were expected to follow. By July, this model too had failed to even minimally correspond to observed reality. ICL attempted to save face by publishing an absurd exercise in circular reasoning in the journal Nature where they invoked the unrealised projections of their own model to supposedly “prove” multiple millions of lives had been saved by the lockdowns. That study soon failed basic robustness checks when the ICL team’s suite of models were applied to different geographies.

Another team of Swedish researchers then noticed oddities in the ICL team’s coding, suggesting they had modified a key line to bring data from their own comparative analysis of Sweden into sync with other European countries under lockdown after the models did not align. A published derivative of this discovery showed that ICL’s own attempts to validate the effectiveness of its lockdown strategies does not withstand empirical scrutiny.

Finally, in November, another team of researchers from the United States compared a related ICL team model for a broader swath of countries against five other international models of the pandemic, examining the performance of each against observed deaths. Their results contain a stunning indictment: “The Imperial model had larger errors, about 5-fold higher than other models by six weeks. This appears to be largely driven by the aforementioned tendency to overestimate mortality.”

The verdict is in. Imperial College’s COVID-19 modelling has an abysmal track record – a characteristic it unfortunately shares with Ferguson’s prior attempts to model mad cow disease, swine flu, avian flu, and countless other pathogens.

Not only did Ferguson’s modelling overstate mortality in the absence of restrictions, it also grossly exaggerated the effectiveness of restrictions in reducing deaths.

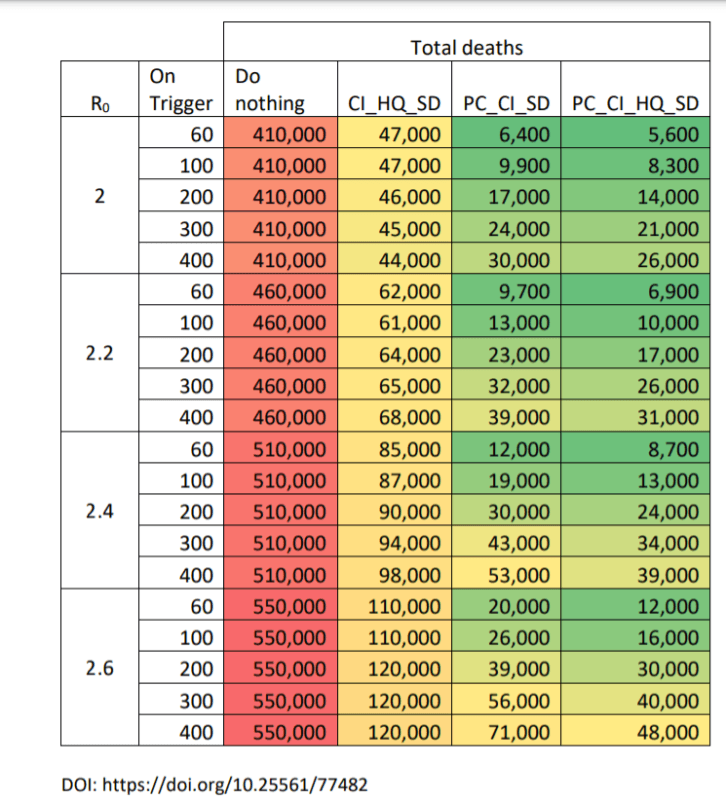

Here are the report’s projections for the different scenarios:

These projections for deaths in the presence of strong restrictions were far too low – and it’s worth recalling that the Imperial team went public in the first week of lockdown in March 2020 to predict just 5,700 UK Covid deaths in the spring under the restrictions imposed at the time. The actual spring death toll was around 40,000.

Phillip writes:

As of the one-year anniversary, the UK had a little over 125,000 confirmed COVID-19 deaths. By implication, the UK death toll has exceeded the mildest of the other three NPI scenarios from the ICL model (column 2) and blown past its heavier NPI recommendations (columns 3 and 4), even while operating under a more stringent set of lockdowns than ICL originally contemplated.

The implications are clear. While Ferguson wildly exaggerated the “worst case” scenario for the UK, he also severely overestimated the effectiveness of NPIs at controlling the pandemic.

By building its policy response around the Imperial College model, the UK Government delivered the worst of both worlds. It imposed some of the most severe and long-lasting lockdowns in the world based on the premise that NPIs would work as Ferguson’s team predicted, and that such actions were needed to avert a catastrophe. Except the lockdowns did not work as intended, and the UK also ended up with an abnormally high death count compared to other countries – including locales that did not lock down, or that reopened earlier and for longer periods than the UK.

Why is Ferguson’s Covid modelling so poor? Phillip suggests two reasons. First, as Ferguson himself made clear in his 2006 flu model on which the Covid model was based, it does not properly take into account spread in “residential institutions (for example, care homes, prisons) and health care settings”. When 40% of deaths are care home residents and up to two thirds of infections leading to serious illness are contracted in hospital, this is a major omission.

Second, it exaggerates the impact of restrictions on community transmission, seeming to pluck the assumptions about how much each intervention would reduce spread out of thin air. With good reason, this form of analysis was dismissed by the WHO in 2019 as not offering a reliable basis for public health policy. Phillip writes:

A 2019 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) warned of the flimsy empirical basis for epidemiology models such as the one developed by ICL. “Simulation models provide a weak level of evidence,” the report noted, and lacked randomised controlled trials to test their assumptions. The same report designated mass quarantine measures – what we now know of as lockdowns – as “Not Recommended” due to lack of evidence for their effectiveness. Summarising this literature, which included the same 2006 influenza model that Ferguson adapted to COVID-19, the WHO concluded: “Most of the currently available evidence on the effectiveness of quarantine on influenza control was drawn from simulation studies, which have a low strength of evidence.”

As I have written before, it is admittedly counterintuitive that restrictions do not limit the spread and death toll of coronavirus in the way Ferguson and co expected. However, the data are clear that they do not, with countries and states with fewer or no restrictions frequently outperforming countries and states with some of the most strict. Since asymptomatic carriers are (despite common claims) barely infectious and account for a negligible proportion of spread, we must assume that community transmission is being driven primarily by symptomatic people who are not currently self-isolating – perhaps because they cannot, or cannot afford to, or because they think it is just a mild cold. Since even in a lockdown around half the workforce are travelling to work while only around a third work exclusively from home, many people still use supermarkets and other shops, and many children still attend school (even where the schools are only open for key workers’ children), there’s still plenty of opportunity to spread the virus.

Whatever the explanation, though, the data are unambiguous, and they do not validate Imperial’s modelling, either in terms of how many would die without restrictions or how few would die with them.

The trouble is that the assumptions behind the modelling – that lockdowns control the virus and without them hundreds of thousands more would die – have become accepted truth, to the point that journalists will just state it in their reporting as though it is undisputed fact, and politicians will instinctively impose or tighten restrictions as soon as positive cases start to rise with little or no opposition.

But you cannot ignore reality forever. At some point something has to give. Any day now…

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.