In a recent article, we considered the implications of the U.K.’s spring rise in infections, given that before now the assumption has been that coronaviruses are seasonal at northern temperate latitudes. Do we have to dismiss that hypothesis in light of the ‘Third Wave’?

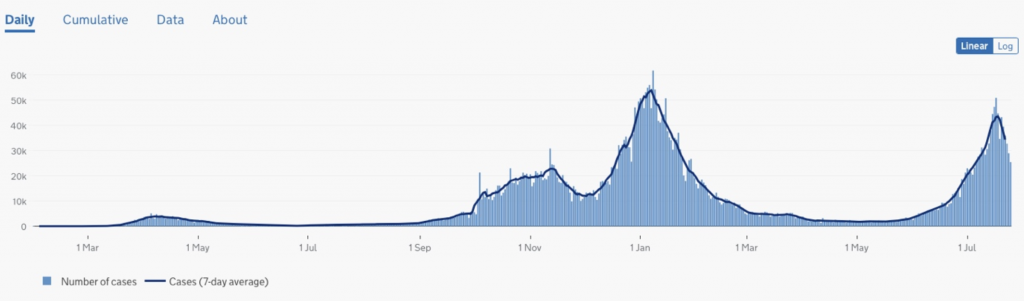

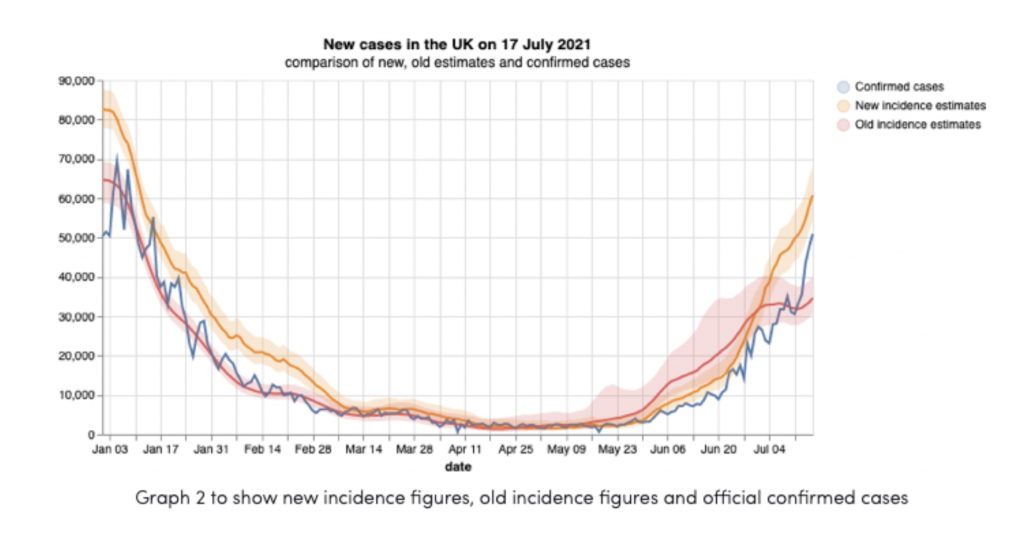

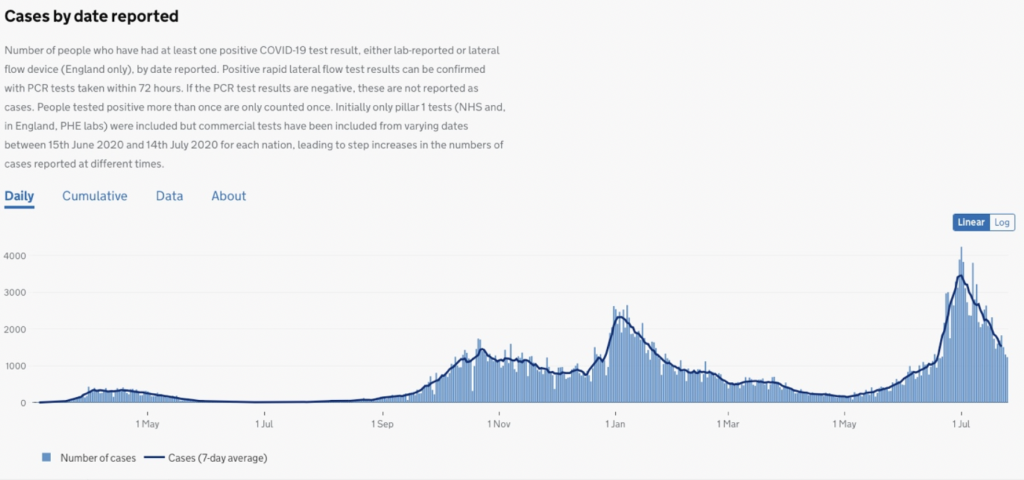

Here we argue that, contrary to Government claims, the British summer is indeed finally impacting viral transmission, with sharp falls in positives reported across the U.K. In England, reported cases have more-or-less halved in a week, from 50,955 to 25,434.

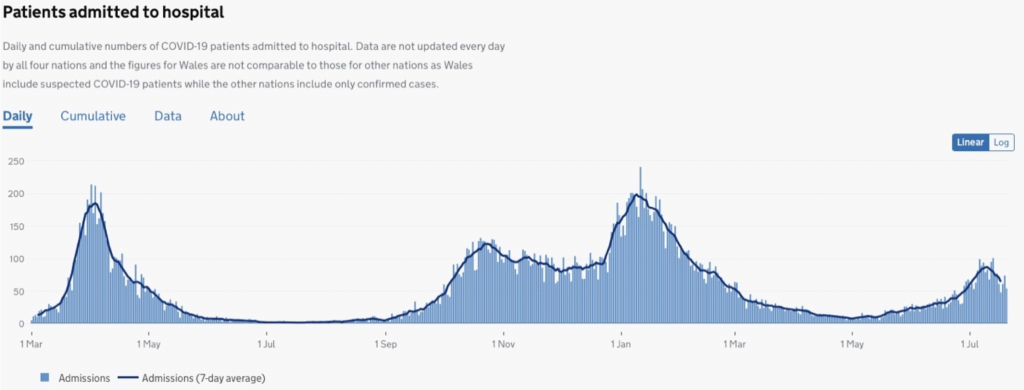

This sharp fall runs counter to all three of the most recent SAGE models driving Government policy, which predict rising infections leading to peaks in hospital admissions in high summer – and by implication falsifies the assumptions upon which these models are based.

Parsimony predicts the summer troughs and winter peaks evident for SARS-CoV-2

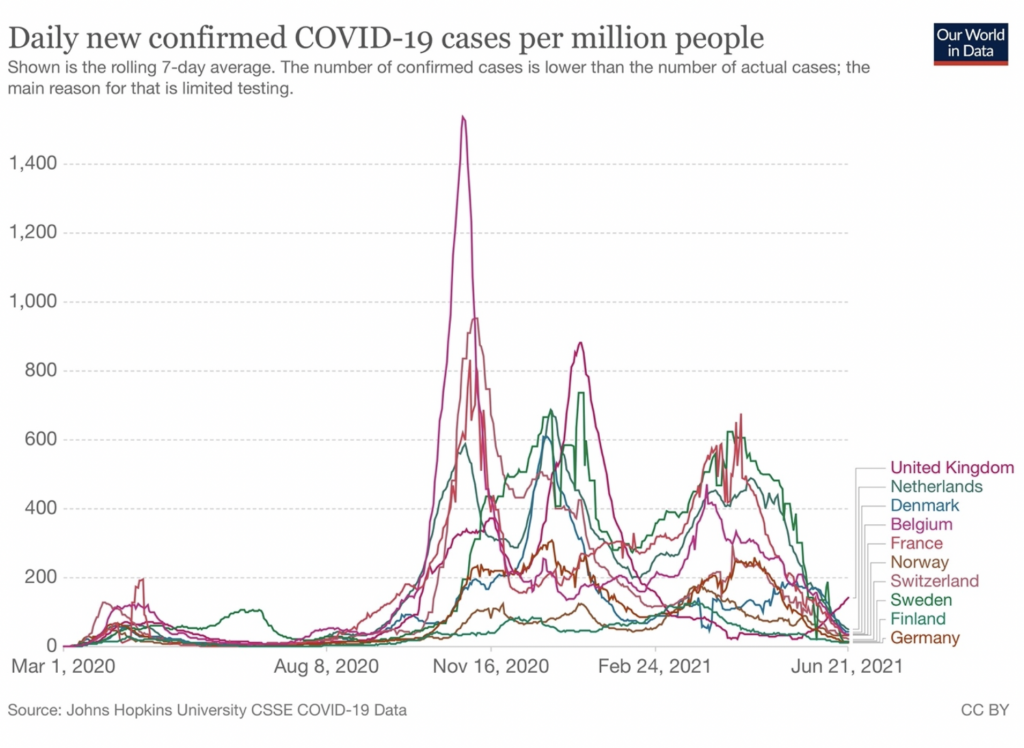

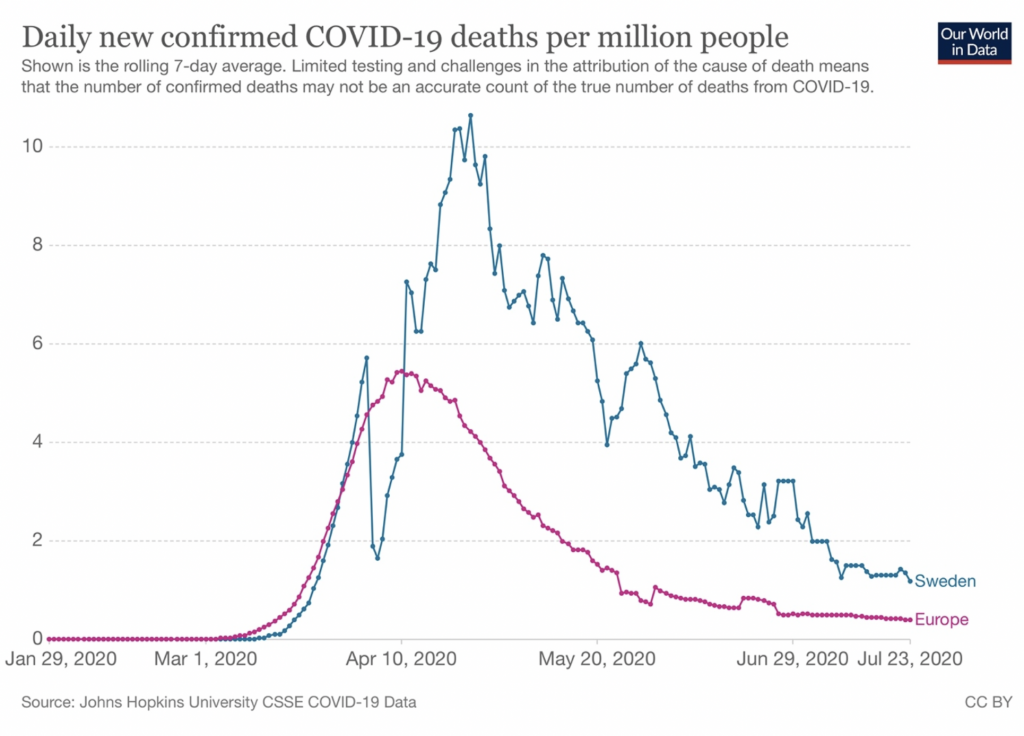

In spring and summer 2020 and winter 2020-1, SARS-CoV-2 infections parsimoniously followed the pattern of seasonal respiratory viruses, falling away in the summer months and rising again in the autumn, with peaks in deaths occurring between mid-November 2020 and mid-April 2021 in different northern temperate countries.

Although falling infection levels were sometimes prolonged into early summer or began to rise again in late summer, there were no peaks in fatalities in summer or early autumn 2020.

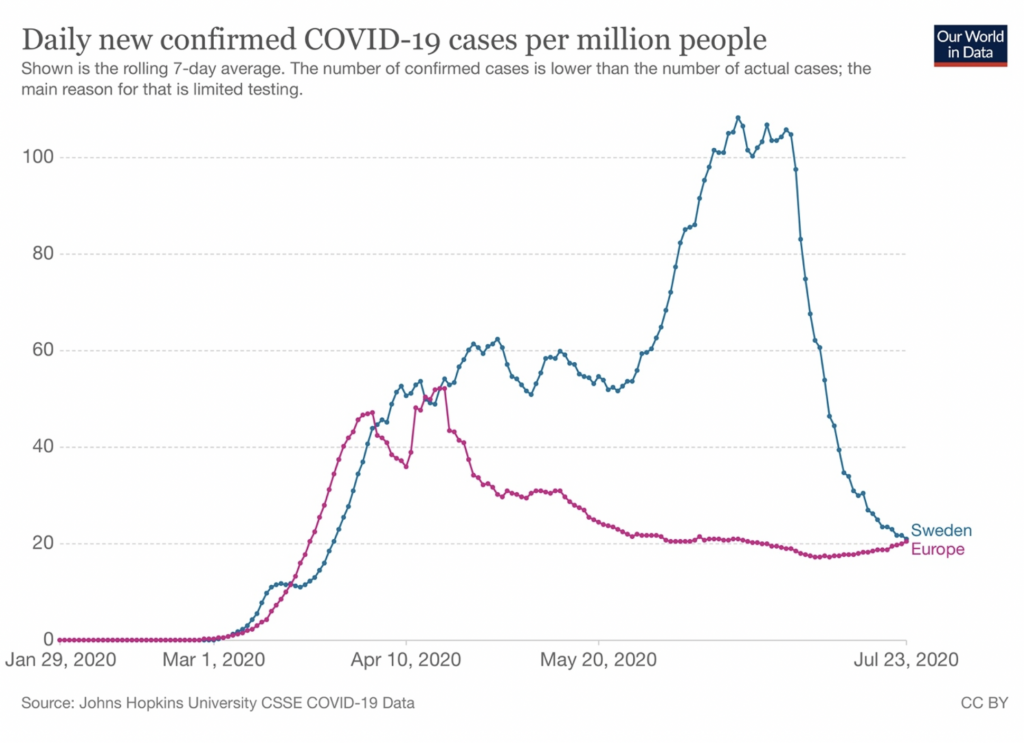

Most notably, while cases in Sweden rose in a pattern close to the European average in early 2020, they persisted much later, continuing to a plateau in late spring and early summer, before falling away sharply from the end of June. Hospitalisations and deaths fell more smoothly from the mid-April peak, however, and showed no corresponding rise in late spring and early summer.

Similarly, while infections began to rise in late summer in some countries – such as France – there was no substantial increase in deaths before mid-autumn. Summer 2020 appears to have broken the link between infections and serious illness in the absence of vaccination.

Sweden has so far emerged relatively unaffected by the Delta variant. Although this variant was detected in Sweden – as it was in most other European countries – infections in Sweden nevertheless fell with the onset of summer. As Sweden’s State Epidemiologist Anders Tegnell remarked in an interview on June 18th, 2021 (at about 8 minutes 25 seconds), “the number of cases in Sweden are falling rapidly, very rapidly I would say, much more rapidly than we ever thought was possible”. Tegnell also makes some sceptical points about asymptomatic transmission and mass testing, so beloved of the U.K.’s SAGE committees.

Recent peaks attributable to the Delta variant have occurred in countries such as Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands, but these outbreaks too may have peaked as they appear to have in the U.K.

SAGE scenarios – anything can happen in the next eight weeks…?

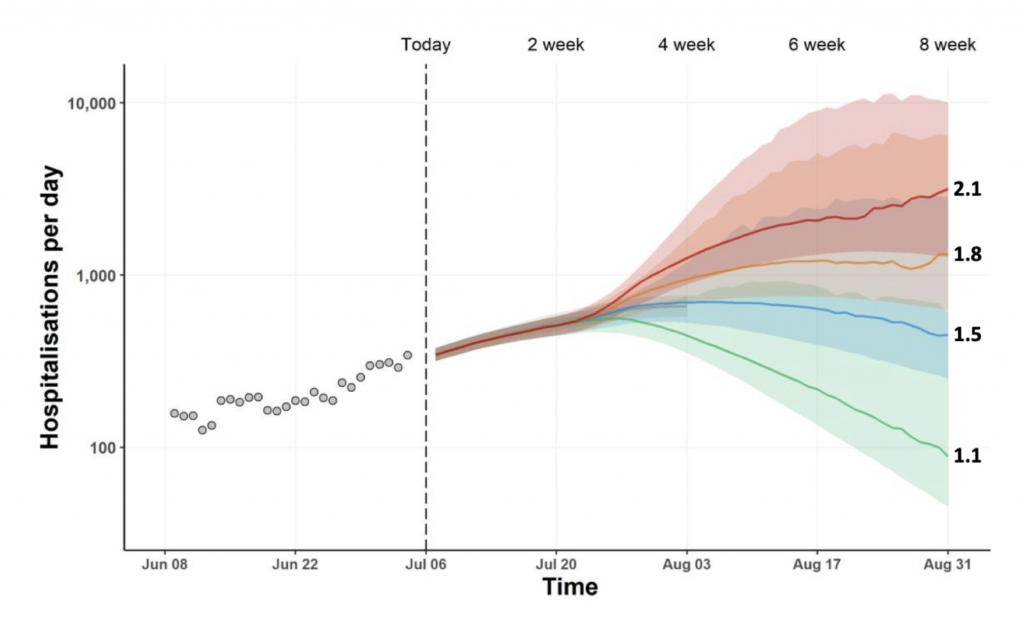

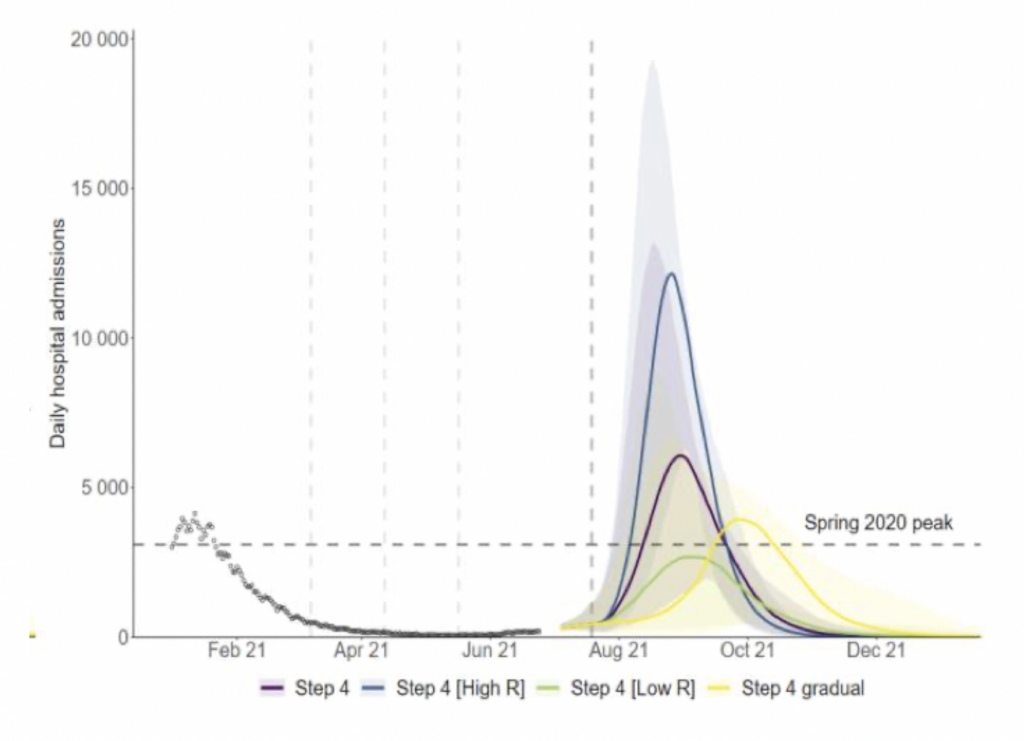

Turning to the latest (July 6th) scenarios of the SAGE’s SPI-M-O modelling groups, we find hospitalisations could be between 50 and 10,000 per day by August 31st depending on the R value. SPI-M-O note these scenarios are not forecasts or predictions, leaving open to question their purpose with regard to Government formulation of policy.

Previous over-estimations of hospitalisations are attributed to: 1) the cancellation of ‘Freedom Day’ on June 21st permitting more vaccinations to be administered and transmission to be delayed due to restrictions; 2) less than anticipated mixing between adults since late April to mid-May; and 3) the effectiveness of vaccines against the Delta variant.

There appears to be no suggestion of an emphatic effect of spring and summer on behaviour, the virus or viral transmission, which would have been considered conventional wisdom until mid-March 2020.

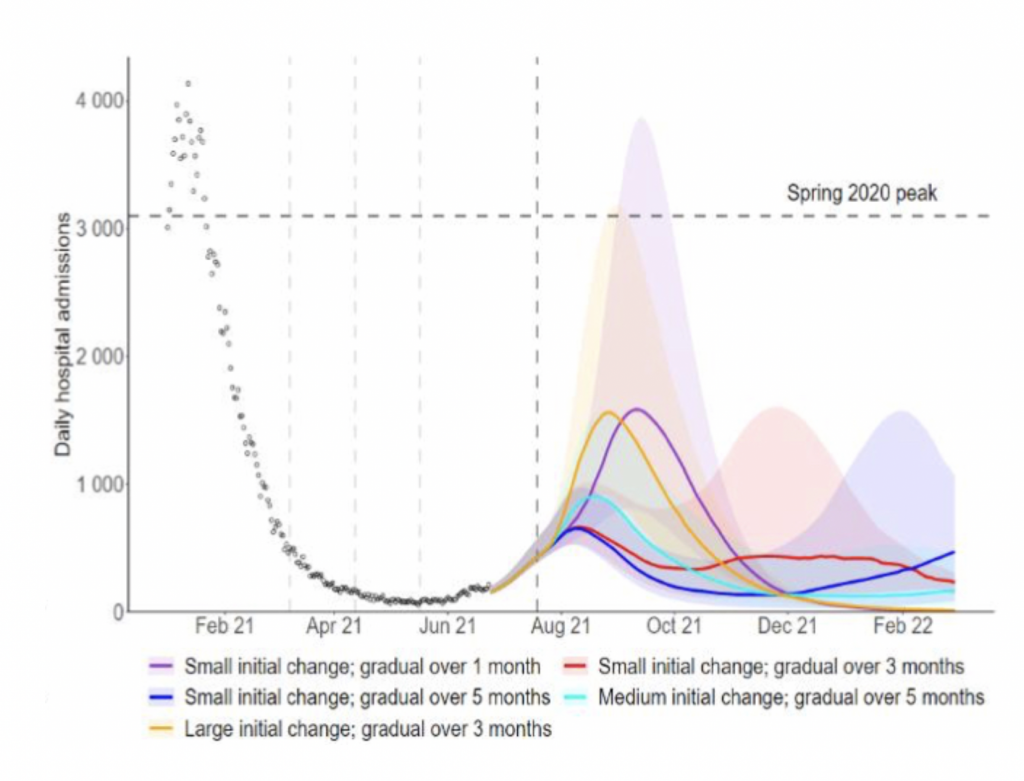

Warwick University

The Warwick models predict the current rise in hospitalisations will persist to peak in late summer or early autumn, which may or may not be accompanied by a small wave – based on the mean estimates – from late December 2021 or early February 2022 depending on supposed “precautionary behaviour”.

None of the Warwick models predict a fall in hospitalisations in summer 2021 nor – by implication – a fall in infections.

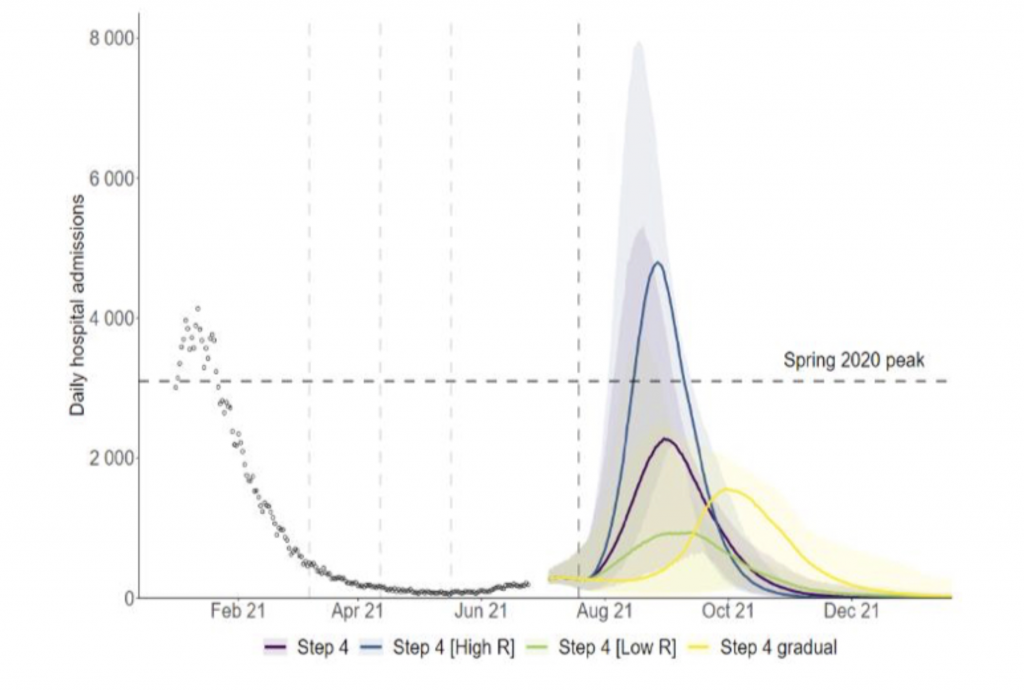

Imperial College London

Imperial College offers two models, based on optimistic (upper figure) and central (lower figure) estimates of vaccine effectiveness, adjusted according to estimates of the speed of change in behaviour and the R value.

Both models predict peaks in the early autumn, possibly delayed to mid-autumn if changes in behaviour are slow. Using these assumptions, the mean estimates presented for hospitalisations are higher than in the Imperial models.

Central estimates of vaccine effectiveness with sudden relaxation in precautionary behaviour appears to predict mean daily hospitalisations of about 2,500 to about 12,000 per day by the end of September depending on the R value. Imperial have produced a further model based on pessimistic estimates of vaccine effectiveness (not shown).

Of the Imperial models, only the gradual relaxation of restrictive behaviour scenarios indicate a fall in hospitalisations, but in both instances this simply delays a peak in hospitalisations and – by implication – infections until the early autumn. Neither model anticipates an imminent fall continuing into summer, nor a winter peak between December and February.

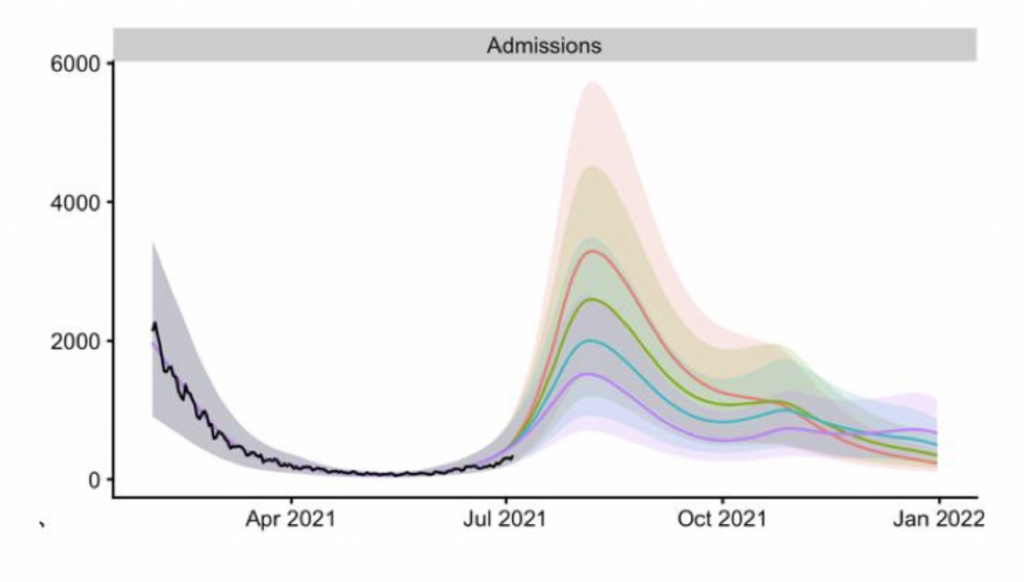

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)

LSHTM present similar models based on a further set of assumptions and predict a peak in hospitalisations in mid-summer, varying in size according to the extent of reduction in transmission (five to 20% reduction at medium mobility is shown in the figure).

Again, the LSHTM model precludes the current reduction to a baseline as in summer 2020.

The ZOE Symptom Study, which provides invaluable independent comparator to reported positives figures, appears to show infections to be rising to July 20th, but only since the method of estimation was revised. Comparators such as ONS and REACT-1 are out of date.

Implications of the models

None of the SAGE models predict a sharp fall and summer lull in infections. Rather, the SAGE report states “the prevalence of infection will almost certainly remain extremely high for at least the rest of the summer”.

We are left with two competing hypotheses:

SAGE predict a continued rise in infections, accompanied by hospitalisations and deaths, peaking in mid-summer or early autumn. There may be a further small wave from late December or early February, or none at all.

Parsimony predicts cases will fall to baseline as summer advances, much as occurred in Sweden last year – a late spring or early summer cold that does not cause significant morbidity or mortality. The summer disappearance will be followed by a resumption in the autumn rising to a peak in infections and deaths in winter proper.

Are the SAGE models already wrong?

Although summer peaks in infections in seasonal respiratory viruses are rare, they are not unknown, particularly in novel varieties and, it may be noted that – unlike in Sweden in 2020 – the spring rise in infections in the U.K. arose from a low base and involved a new variant – the Delta variant – and was preceded by the vaccine roll-out.

While vaccination is argued to be the key factor in keeping hospitalisations and deaths figures low, these measures were also low in the late spring 2020 wave of infections in Sweden. It is possible that nosocomial and care-home outbreaks have also been prevented, in part due to the seasonal fall in general demand for hospital beds in the spring and summer. The most recent ONS report shows overall excess deaths in England and Wales to be higher at home than in care homes or hospitals. Nevertheless, it is striking that reported positives in Scotland have been falling since the end of June.

Hospitalisations in Scotland are also falling from a peak approximately a week later.

The rest of the U.K. is now following the trend in Scotland, which showed a rapid fall in infections from the end of spring and beginning of summer, as Sweden did in 2020. Are we simply experiencing a late impact of seasonality on suppression of spread, which has finally taken effect?

Reported positives peaked just prior to ‘Freedom Day’ in England and about three weeks earlier in Scotland. There is no sign of any stall in the falling trajectory of infections in either country, as could be attributed to the relaxation of restrictions on ‘Freedom Day’. This would be not at all surprising to those who observed the lack of impact of ‘opening up’ in Texas and Florida some months ago.

On the basis of current infection data, the SAGE models are already wrong.

So must be the assumptions of virus transmission and effects of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions – and lack of effect of nature – on which they are based.

It begs the question as to why the Government and media have again so enthusiastically engaged with consistently disappointing predictions leading to such damaging public health policy.

None of this should be a distraction from the point that lockdowns cause a good deal of harm to physical and mental health and to the economy, far outweighing any presumed benefit – if any can be shown. The models, NPIs and lockdowns are about politics, not science.

The co-authors are a PhD epidemiologist trained at a Russell Group University and a retired former Professor of Forensic Science and Biological Anthropology.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpEnd of Self-Isolation Rules for Fully Vaccinated Could Be Delayed Beyond August 16th

Next PostCan We Say, Definitively, that the SAGE Models are Wrong?