by Mike Hearn

It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgement of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Marcia Angell

Check out this image from a peer reviewed research paper that supposedly shows skin lesions being treated by a laser:

On being challenged the authors said:

The photograph was taken in the same room with a similar environment; unfortunately the patient wore the same shirt.

The journal found this explanation acceptable and forwarded the response to the complainants.

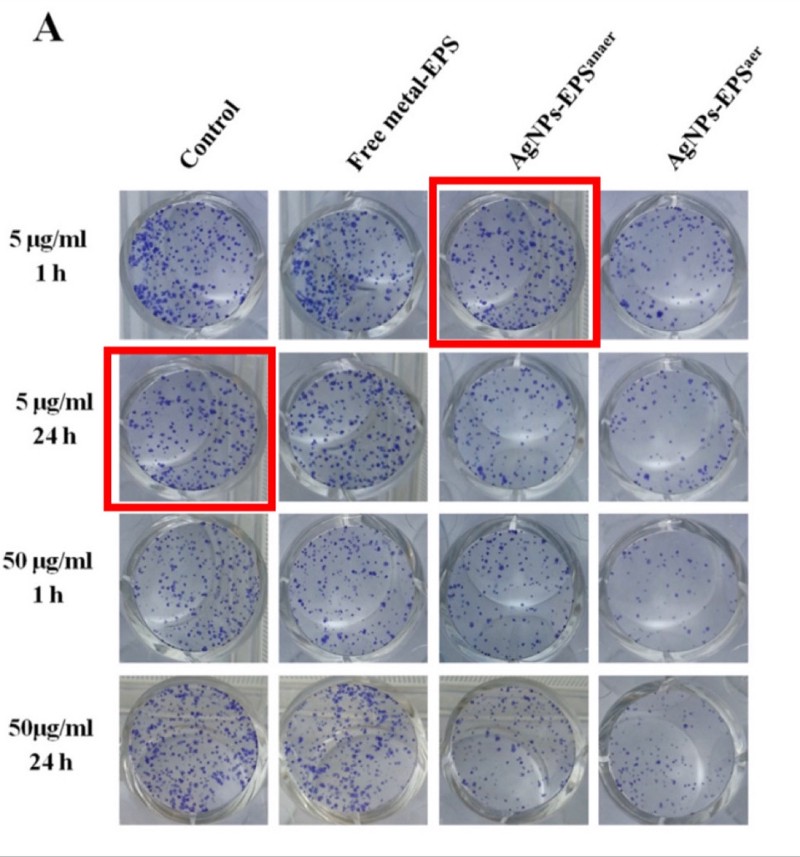

It’s becoming clear that science has major difficulties with not only a flood of incorrect and intellectually fraudulent claims, but also literally faked, entirely made up papers with random data, imaginary experiments and photoshopped images in them. Some of these papers are sold by organised gangs to Chinese doctors who need them to get promoted. But others come from really sketchy outfits like (sigh) the National Health Service, to whom we owe the masterpiece seen above.

The British Government hasn’t noticed that its doctors are massaging medical evidence. Instead this example comes from Elizabeth Bik, who runs a blog where she and a few other volunteers try to spot clusters of fraudulent papers. She embarrassed the journal in public here, and the paper was finally retracted. But she’s just a volunteer who raises money on Patreon for her work. Here’s her assessment of what’s going on:

Science has a huge problem: 100s (1000s?) of science papers with obvious photoshops that have been reported, but that are all swept under the proverbial rug, with no action or only an author-friendly correction… There are dozens of examples where journals rather accept a clean (better photoshopped?) figure redo than asking the authors for a thorough explanation.

As the only people trying to spot these fake papers are bloggers, we can safely assume that far larger numbers of papers are fake than the “thousands” they have already found and reported. For example,

0.04% of papers are retracted. At least 1.9% of papers have duplicate images “suggestive of deliberate manipulation”. About 2.5% of scientists admit to fraud, and they estimate that 10% of other scientists have committed fraud.

It’s been known for years that a lot of claims made by scientists can’t be replicated. In some fields, the majority of all claims appear to not replicate due to a large mix of issues like overly lax thresholds for claiming statistical significance, poor study design and other somewhat subtle errors. But how much research is deliberate falsehood?

The sad truth is the size of the fraud problem is entirely unknown because the institutions of science have absolutely no mechanisms to detect bad behaviour whatsoever. Academia is dominated by (and largely originated) the same ideology calling for the total defunding of the police, so no surprise that they just assume everyone has absolute integrity all the time: research claims are constantly accepted at face value even when obviously nonsensical or fake. Deceptive research sails through peer review, gets published, cited and then incorporated into decision making. There are no rules and it’d be pointless to make any because there’s nobody to enforce them: universities are notorious for solidly defending fraudulent professors.

So let’s turn over the rock and see what crawls out. We’ll start with China and then turn our attention back to more western types of deception.

Chinese fraud studios

In 2018, the U.S. National Science Foundation announced that: “For the first time, China has overtaken the United States in terms of the total number of science publications.” Should the USA worry about this? Perhaps not. After some bloggers exposed an industrial research-faking operation that had generated at least 600 papers about experiments that never happened, a Chinese doctor reached out to beg for mercy:

Hello teacher, yesterday you disclosed that there were some doctors having fraudulent pictures in their papers. This has raised attention. As one of these doctors, I kindly ask you to please leave us alone as soon as possible… Without papers, you don’t get promotion; without a promotion, you can hardly feed your family… You expose us but there are thousands of other people doing the same. As long as the system remains the same and the rules of the game remain the same, similar acts of faking data are for sure to go on. This time you exposed us, probably costing us our job. For the sake of Chinese doctors as a whole, especially for us young doctors, please be considerate. We really have no choice, please!

Note the belief that “thousands of other people” are doing the same, and that these doctors need more than one paper to keep being promoted, so the 600 found so far is surely the tip of an iceberg given China’s size. There are about 3.8 million doctors in China implying that there are quite possibly tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of these things in circulation.

The fake papers are remarkable:

- They are so good they are undetectable in isolation. The NHS photo is an aberration – normally these papers get spotted by noticing re-used technical images across papers that claim to be different experiments by different people. The fake papers are probably produced by real scientists with access to real lab equipment. The use of spammy-looking Gmail accounts is also a signal because Gmail is banned in China (e.g.

BrendaWillingham12192@gmail.com,RosettajKirkland3814@gmail.com,CaseyPeiffer8311@gmail.com). The reliance on bot-generated Gmail accounts implies enormous scale. - They are peer reviewed and published in western journals. For instance, the Journal of Cellular Biochemistry by Wiley or Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy by Elsevier. They claim to be doing advanced micro-biology on serious diseases: a typical title is something like “MicroRNA-125b promotes neurons cell apoptosis and Tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease”. Journals have no way to detect these papers and aren’t trying to develop any.

- Some of them present traditional Chinese medicine as scientific. TCM is more or less the Chinese equivalent of homeopathy with lots of herbal remedies, eating body parts of exotic animals to cure erectile dysfunction, and so on. But the Chinese Government is obsessed with it and thinks it’s the same as normal medicine. From the top down, Chinese scientists are expected to produce papers claiming that TCM works, and they do! Mostly this stuff stays in Chinese but the ever increasing reliance of western universities on Chinese funding means it’s now finding its way into the English language literature as well, e.g. “Probing the Qi of traditional Chinese herbal medicines by the biological synthesis of nano-Au” was published by the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Most western scientists are too clever to buy a completely fake paper (or so we hope). But their promotion incentives are identical, and there are other techniques that let you publish as many fake papers as you want. Let’s turn our attention to…

Impossible numbers in western science

The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue.

Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet

How many scientists just make up their data? A well known recent case of this was the Surgisphere scandal, in which a paper appeared in The Lancet that claimed to be based on a proprietary dataset of nearly 100,000 COVID-19 patients across over 670 U.S. hospitals. This figure was larger than the official case counts of some entire continents at the time, and there was no reason for hospitals to share tightly controlled medical data with a random company nobody had heard of, so the claim was implausible on its face. Sure enough, when challenged it turned out none of the authors had ever actually seen the data, just summaries of it provided by one guy, who on investigation had a long track record of dishonesty. The Lancet probably accepted this paper because it made Trump look bad and the editor (Horton, quoted above) appears to hate Trump more than he hates bad science.

There are some other cases like this that came to light over the years, like the story of Brian Wansink, or that of Paolo Macchiarini, who left a trail of dead patients in his wake. But while anecdotes about individual cases are interesting, can we be more rigorous?

One clue comes from automated tools that scan research papers looking for mathematically impossible numbers, which can sometimes be detected even in the absence of the raw original data. In recent years a few such tools have been developed and deployed, mostly against psychology and food science.

- The statcheck program showed that “half of all published psychology papers… contained at least one p-value that was inconsistent with its test”.

- The GRIM program showed that of the papers it could verify, around half contained averages that weren’t possible given the sample sizes, and more than 20% contained multiple such inconsistencies.

- The SPRITE program detected various experiments on food that would have required subjects to eat implausible quantities (e.g. a child needing to eat 60 carrots in a single sitting, or 3/4 kilogram of crisps).

Being flagged by a stats checker doesn’t guarantee the data is made up: GRIM can detect simple mistakes like typos and SPRITE requires common sense to detect that something is wrong (i.e., no child will eat a plate of 60 carrots). But when there are multiple such problems in a single paper, things start to look more suspicious. The fact that half of all papers had incorrect data in them is concerning, especially because it seems to match Richard Horton’s intuitive guess at how much science is simply untrue. And the GRIM paper revealed a deeper problem: more than half of the scientists refused to provide the raw data for further checking, even though they had agreed to share it as a condition of being published. This is rather suspicious.

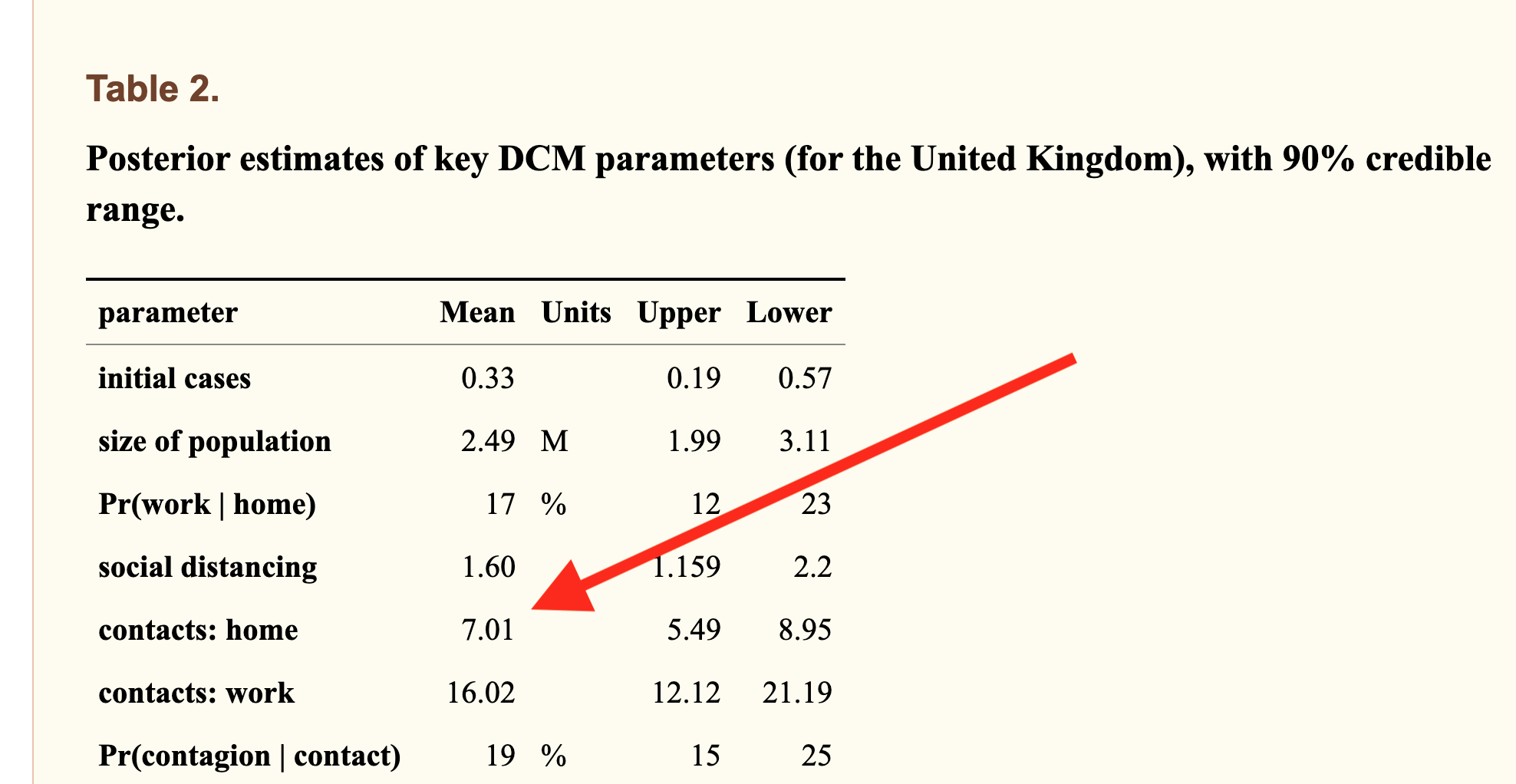

One of the difficulties with detecting scientific fraud is that the line between dishonesty and simple absurdity can get quite blurry. Sometimes scientists “calculate” data that is clearly wrong, but don’t actually try to hide or it may even admit to it in the paper, knowing full well that nobody cares and nonsensical data won’t actually matter. Here’s an example from a COVID modelling paper:

The model was allowed to calculate that the average Brit must live with 7 other people, because it couldn’t obtain data fit otherwise (actual number=2.4). This one comes from University College London, is written by 12 neuroscientists, passed peer review and has 37 citations. The peer reviewer noticed that the incorrect number was in the paper but signed off on it anyway.

For decades psychiatrists published research into the “gene for depression” 5-HTTLPR. They created an entire literature not only linking the gene to depression but explaining how it worked, linking it to parenting styles, developing treatments based up on it. Over 450 papers were published on the topic. Eventually a geneticist discovered what they were doing and used DNA databanks to point out that none of those papers could possibly be true.

Sometimes numbers aren’t “wrong” but are instead logically vacuous. The Flaxman et al paper from Imperial College that tried to prove lockdowns work had the usual problem of statistically implausible numbers, but more importantly was built on circular logic: their model assumed only government interventions could end epidemics. This is obviously nonsense and they breezily admitted it in the paper, where they said their work was “illustrative only” and that “in reality even in the absence of government interventions we would expect Rt to decrease”. No problem: this fictional illustration got published in Nature and the authors presented the model’s outputs as scientific proof of their own assumption to the media. The paper is vacuous mathematical obfuscation, but scientists either can’t tell or don’t care: it has racked up over 1,300 citations and the number is still growing rapidly. To put that number in perspective, in physics the top 1% of all researchers have around 2,000 citations over their entire career.

Time to assume that health research is fraudulent until proven otherwise?

Earlier this month, the BMJ published an astounding blog post with the same title as this section. There’s no need to add anything because simply quoting it is sufficient:

The anaesthetist John Carlisle analysed 526 trials submitted to Anaesthesia and found that… when he was able to examine individual patient data in 153 studies, 67 (44%) had untrustworthy data and 40 (26%) were zombie trials… [Ben] Mol’s best guess is that about 20% of trials are false. Very few of these papers are retracted.

Richard Smith

We have now reached a point where those doing systematic reviews must start by assuming that a study is fraudulent until they can have some evidence to the contrary.

Richard Smith is a former editor of the BMJ, cofounder of the Committee on Medical Ethics (COPE), for many years the chair of the Cochrane Library Oversight Committee, and a member of the board of the U.K. Research Integrity Office.

Or put another way, an overseer of the Research Integrity Office believes research has no integrity.

What can be done?

600 fraudulent papers here, 450 over there, 1300+ citations of just one bad paper… pretty quickly it starts adding up.

We’re often told science is self-correcting. Is that true? Probably not. “The Science Reform Brain Drain” is perhaps the bleakest essay I’ve read this year. Reformers like the men who developed SPRITE and GRIM have been giving up and leaving science entirely. Pointing out in public that your colleagues are dishonest is never a great career move, and the work was often futile. One scientist who quit and went into industry summed up his fraud detection work like this:

The clearest consequence of my actions has been that Zhang has gotten better at publishing. Every time I reported an irregularity with his data, his next article would not feature that irregularity.

Even when a bull enters the China shop and gets a few papers retracted, it doesn’t actually matter because it has little effect: retracted papers keep getting cited for years afterwards and actually may be cited more than non-retracted papers, because one of the effects of retraction is that the article becomes free to download.

In the past year most talk of bad science has been about models with bad assumptions. This is an issue but has been hiding problems that are far worse: scientists are buying fake papers, Photoshopping evidence, refusing to upload their data, knowingly publishing numbers that cannot be correct, citing papers that were retracted for being fraudulent and (of course) presenting mathematical obfuscations of what they want to be true as if it were science. Journals usually ignore fraud reports entirely, or when put under pressure let scientists submit “corrected” versions of their papers. And worst of all, the journal editors that are responsible for scientific gatekeeping know all this is happening, but aren’t doing anything about it.

In fact, very little can be done because above all, universities rely on reputation and don’t want anyone to find out about bad behaviour, so they fight tooth and nail to protect academics no matter how badly they are behaving. There are no rules. Any rules that are alleged to exist turn out when tested to be illusions.

Claims made by scientists are automatically trusted by the majority of people. Maybe they shouldn’t be?

Mike Hearn is a former Google software engineer. You can read his blog at Plan 99.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Yes pricing is an issue, but also Machete wielding lunatics trying to chop everyone’s heads off probably play a role too.

” tourist numbers remain below pre-pandemic levels”

What pandemic was this? I remember lockdowns and other restrictions on normal life, imposed by our and other governments and I remember being told there was a “pandemic” but I never saw or read any compelling evidence pointing to it being real – just stuff about “cases” and “deaths” based on a “test”, none of which were meaningful or properly defined. Just after “lockdowns” were declared, an unusual number of mainly old people died in a short space of time, but the reasons for this could be various and not necessarily “covid”.

“Just after “lockdowns” were declared, an unusual number of mainly old people died in a short space of time, but the reasons for this could be various and not necessarily “covid”.”

Come on tof, stop being cutesy – Midazolam Mat.

Certainly the most likely explanation along with general denial of care/drop in care standards.

Exactly that!

Cheers Ron.

Never Forget, Never Forgive.

Given Kneel’s wholehearted commitment to utterly destroy our country I am sure he and Robber Reeves will be delighted with this news. Sadly, the collapse in our hospitality standards and inexorably rising prices has done nothing to deter the Calais Yatch Club arrivals. Whoops…but they only come to TAKE not give. Silly me.

Realistically though why would anyone want to visit this country? Everywhere we go, every town and city is full of non Brits wandering about jabbering away in anything but English and wearing pyjamas while their women have their faces covered for some obscure reason not linked to the C1984.

Anyway, more WEF browny points for Starmer Feuhrer.

They are probably just using the main cities as an airport Hub. I used Birmingham Airport and got straight out of there once I got to my car!

The internet means that a Country’s problems are now fully on display for any would be tourists to see. So what do they learn about the UK?

There is permitted violence in the form of the Palestine protests in London, which have resulted in the defacement of some of the national treasures that tourists would choose to see.

The Museums have now fallen under the spell of re-educstion such that great works of art are either no longer available to be seen, or the visitor is told that they need to be aware that they might be “triggered” by what they see. In addition there is always the possibility that a JSO, Extinction rebellion member will throw dye over them, or glue themselves to the picture.

Then there is the knife crime, the machete incidents, the muggings which are a risk, one example the little Australian girl a tourist with her mother stabbed in Leicester square, how do you think that went down in Australia?

The terrorist offences.

Then there is the general standard of filth in our Cities London stinks of weed, in Tottenham court road human excrement littered the pavement, and tents in various side streets with visibly drunk people inside.

Then the cost of things, the cost of a round of drinks in London and in the Cotswolds for 4 people is circa thirty pounds, the cost of a very average meal won’t see you out with less than 50 quid per head, that’s in a pub, and the service is very rarely service, the guest is made to feel more of a distraction from the mobile phone of the server.

Hotel room costs are a joke, its cheaper to stay in a luxury hotel in Asia than it is in a bog standard hotel in London.

Transport unless its the Elizabeth line is filthy and dispiriting, trains elsewhere are likewise cripplingly expensive, overcrowded and again less than clean.

Yes we have some castles, museums, and places like the Palace of Westminster etc, but as with much else in the UK the citizens have been conditioned to feel shame at these places, as representative of our terrible history, that patriotism and pride in your culture is to be abhored, and so these places look neglected, the staff reflect the state of decay and neglect.

In summary the country to the outsider is dirty, crime ridden, unsafe, expensive and in a state of collapse. Why would you choose to risk a holiday here.

Depressingly well put. I have avoided any cities for years now, but I will not go anywhere near London exactly because of the reasons in your comments. I would have loved to take my grandchildren to visit all the places I took my children, to show them the treasures of our country but it has all been debased and I will not put their safety at risk to even travel on public transport.

I must say not everywhere is tainted by the Globalists (yet at least). Was walking around Hereford the other day, with it being a nice day there was a generally good atmosphere. Events outside of the amusements of kids etc, I used to live there so it was normal for there. But while walking through the back of my mind was full of the dark news events. End of Rome maybe.

You are very wise to protect them. An acquaintance said that he took his wife and kids to London for the first time last summer, to visit their own capital city, and to show them the world-famous historical sights which his own parents had shown him as a child.

He and his wife were utterly shocked to see so many Third World Immigrants swarming everywhere, with few English people to be seen, along with the general atmosphere of dingy, filthy, menacing decay. He hardly knew how to answer his young son when he asked, “Why are all the men wearing pajamas?”

He said he couldn’t believe this had happened in only a couple of decades, and he would never go back there again, or let his children go even on a school trip there.

Here’s an example of public transport in Sweden:

RadioGenoa on X: “”Get up you old Swedish woman, I must sit down now!” How much longer do we have to endure this? https://t.co/SvD9q53THh” / X

Your description of London sounds like it should be twinned with San Francisco!

Off-T

Another excellent article from Colin Todhunter on how the big corporations are working to take over world food production.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/agrarianism-transhumanism-long-march-dystopia/5865602

Todhunter supplies this quote:

Silvia Guerini says [3]:

“The past becomes something to be erased in order to break the thread that binds us to a history, to a tradition, to a belonging, for the transition towards a new uprooted humanity, without past, without memory… a new humanity dehumanised in its essence, totally in the hands of the manipulators of reality and truth”.

Is this not so obviously what has been happening to this country for at least fifty years and which Kneel and Co are now pushing in to overdrive?

They haven’t won yet, we may be at a metaphorical crossroads.

Just go to the main visitor attractions. Arrival at the aitrports and the journey through Britain are depressing. Service at hotels and restaurants is surly and expensive. Service everywhgere is poor because it is based on minimum wage immigrant labour, in the main.

The National Trust displays its wokery at every opportunity as do museums, theatre and other attractions.

Safety concerns have been circulated around the world and the attitude of the elites and the police is hardly encouraging. Removal of VAT refunds for high spending visitors makes a 20 per cent difference to the disadvantage of London.

Good points. And here is the kind of “London Theatre Experience” on offer, entitled “Death of England”, featuring an Ethnic African complaining about racism, and boasting about impregnating the English sister of his English “best friend”.

Then there’s his angst-ridden English “best friend” deciding to wait until his own English father’s funeral to publicly denounce his dad’s “racism”. Perhaps he will also kneel before the theatre audience.

Then there are the two mothers-in-law: one Ethnic African, one English, and we can guess which one is portrayed as the “victim”, and which one the “villain”.

Tickets for Death of England: The Plays | London Theatre Direct

It really feels like the country is returning to the 1970s sometimes

“It really feels like the country is returning to the 1970s sometimes.”

Or perhaps soon to be the 1470’s.

But the 1970’s where? Bangladesh? Syria? Pakistan? Iraq? Afghanistan? –or maybe all of those?

Which is why I referred to 1470. Feudalism incoming. Or maybe even worse for the survivors.

But the 1970 were also better in many ways.

I don’t remember any of this in the 1970s. “The Winter of Discontent”, all the trade union strikes and IRA Catholic Terrorist atrocities can’t compare with this total Alien Invasion.

I agree with Nigel Farage, when he said that in London in the 1980s, “Life was fun!”

I was thinking that the ‘entertainment’ referred to sounds like the political theatre of an earlier era. The air of general decay and cultural malaise, too. Granted there were grounds for optimism then, which I don’t see today, as you say.

Oh, yes, I see what you mean. I meant that at least the towns, cities, villages and workplaces of the UK were still recognisably English/Welsh/Scots/Northern Irish back then, before Andrew Neather bravely revealed the plan to “rub our noses in diversity”.

“…with accommodation costs up by 35.8%, restaurant prices by 28.7%.”

Wot? Despite all that essential, cheap, enriching, immigrant labour?

Interesting article thanks. Especially the bit on pricing, “The CEBR report says that overall prices in the U.K. for 2024 are expected to be 23.5% higher than in 2019, with accommodation costs up by 35.8%, restaurant prices by 28.7%, and airfares by 47.6%.”

The Fake News tells me that inflation is low…..in the past 10 years some products have gone up 50%… for people from ‘weak currency’ countries, the UK is increasingly unaffordable to visit. Rona, Net-tard zero, massive immigration, etc etc to blame. But I am sure the BBC will find a way to blame ‘Brexit’….

The airport experience both arriving and leaving is uniformly horrendous.

And once you’re here, prices are high quality is let’s say variable.

Destinations such as museums display an unpleasant level of cynical self hate, so why would anybody spend gazillions taking their kids there.

The weather and the traffic are hideous, and our cities, where most tourists would go are run by metropolitan councils whose main concern seems to be to make a misery for all. Parking impossible, boarded up shops, and a lack of care and maintenance.

Pubs closing, idiotic petty rules everywhere…I’m amazed anybody still wants to visit.

Here’s a rare cheerful snippet from Germany, showing Ethnic Europeans at their best:

Klaus Arminius on X: “A Scotsman lost his iPhone and these Germans found it, they took a selfie and hand it over to the police. Normally phones that are lost are found in Morocco, Algeria or some African country. https://t.co/viwJijNIwH” / X

Let’s see if I lived in Alabama would I want to visit London? I realise that crime exists everywhere, but when was Alabama last in the news for Palestinian Marches, Pitched Machete battles in broad daylight, gangs marauding with knives and guns, a multicultural clutter of disparate groups not integrating, sex crimes and women not feeling safe etc etc etc? ——-Oh but maybe they will feel safe that people are being arrested for being offensive on their laptop

Nothing to do with our shocking summer weather then ?

Britain has certainly lost its attractiveness: overcrowded, expensive and most of the big cities seem to have picked up a certain shabby, slightly menacing atmosphere. I can’t put my finger on what it is, it’s just something that makes you feel uncomfortable.

I have to say though that I had the same feelings in Paris as well the last time I was there.

“most of the big cities seem to have picked up a certain shabby, slightly menacing atmosphere.”

I agree. And the towns in the North West are similarly afflicted.

Britain is also becoming an economically and socially failing state. The unfettered immigration is changing our country into nowhere land. No one wants to go to nowhere.

Except for thrill-seeking tourists from North Africa who pay thousands for the excitement of a trip across the Channel from France by giant inflatable ferries.

Sadly, they can only afford a one-way ticket but not a problem as the inflatables only go one-way.

But what the hell. A holiday is a holiday and it is a holiday of a lifetime or indeed some hope for a lifetime [and not just Christmas, although it seems most don’t celebrate Christian festivals].

Oops – am I going to get banged up in chokey for a couple of years for those remarks?

“Visit Britain ….. the roads are appalling; the trains are expensive and frequently on strike; town centres look like a wasteland; eating-out costs a fortune; the weather’s unpredictable, but usually bad and to top it up, in London and other cities there’s a very good chance you’ll be robbed or stabbed.”

I wouldn’t want to visit London, or a great many other places. It’s OK down here in the west country, which is mostly still recognisably England, but I wouldn’t go anywhere near Bournemouth which is rapidly sliding down into the multi-culti hellhole which has already ruined so many other cities, or Bristol.

It seems not even London’s Mayor likes London.

He feels unsafe here.

And that is despite travelling around in a bomb-proof armoured car with armed close protection.

And it is his job to make sure we all feel safe.

I wonder how he will spin that achievement on his CV?

He claims he does not feel safe as muslim in London.

I am not sure why with all the rate-payer’s money spent on his security.

And that is necessary not because of his religion [which I understand he does not observe nor practice] but because he is so unpopular as a politician with downright crooked ULEZ money-making scheme and other policies so unfair to poor working class white and other peoples.

However, judging by the machete and knife-wielding muslim rioters who have free rein in Birmingham he should resign and stand as Mayor of that great British city safe in the knowledge that his muslim brethren are there to keep him safe from the Far White rioters.

NB ‘Far White’ is not a typographical error. It is not an error at all.

Starmer must really clamp down on the Far White. There are far too many of them, making up about 80% of the population.

They should go back to where they came from.

Erm, what do you mean – they come from here? Are you sure?

I was born in London and worked in the CoL until we moved away over 40 years ago – from what is happening nowadays it was a good move!