There follows a guest post from our in-house doctor drawing on his long experience of working in NHS hospitals to explain why the NHS won’t be resuming normal service for a good while yet. Some of the problems it’s facing were unavoidable, but others were of the NHS’s own making.

In this week’s update, I’m deviating from my usual format of assessing Covid hospital data published by the NHS. It is clear to any objective analyst that we are on the downslope of the Omicron wave, which has fallen far short of predictions by epidemiological experts. Over half of all patients with positive Covid tests in English hospitals do not have Covid as the primary reason for admission, and this proportion has been rising steadily since the new year. There is no reason to believe this trend won’t continue.

This week I turn to the ‘recovery phase’ – where the NHS tries getting back to business as usual. Readers will be wearily familiar with senior NHS figures appearing on the media lamenting the unprecedented pressure the NHS faces. As with many facets of the information space over the last two years, this is partly true. The NHS is under unprecedented pressure – but much of that pressure is self-generated and self-perpetuated, arising from the structure of the system, or from choices made by management.

In this article I will put forward 10 reasons why the machine will not fire on all cylinders for some time, if ever. This is a subjective and observational analysis, not backed up by published data and open to challenge. Some of my points relate to cultural change, where data is hard to collate. On other points, internal data does exist but will never be widely shared or published. I hope this piece will help readers understand why we are where we are – and help them to decipher official announcements in the coming months.

- Loss of efficiency due to Covid protocols: Regulations in respect of Covid testing and periods of self-isolation before surgery are hampering efforts to restore normality. Operating Theatre utilisation rates in many trusts are running at 70% capacity. If a patient tests positive for Covid and is cancelled at short notice, it is not possible to fill the slot because waiting patients don’t fulfil the self-isolation criteria. So, the theatre slot remains empty and is wasted despite the huge backlog.

- Poor management of chronic conditions in the community: Many patients arrive for surgical pre-assessment ill prepared for an operation. This causes postponement and short notice cancellations. The need to optimise poorly controlled underlying conditions before surgery consumes yet more medical resources. In normal times, chronic disease management is the function of the Primary care sector, i.e. GPs.

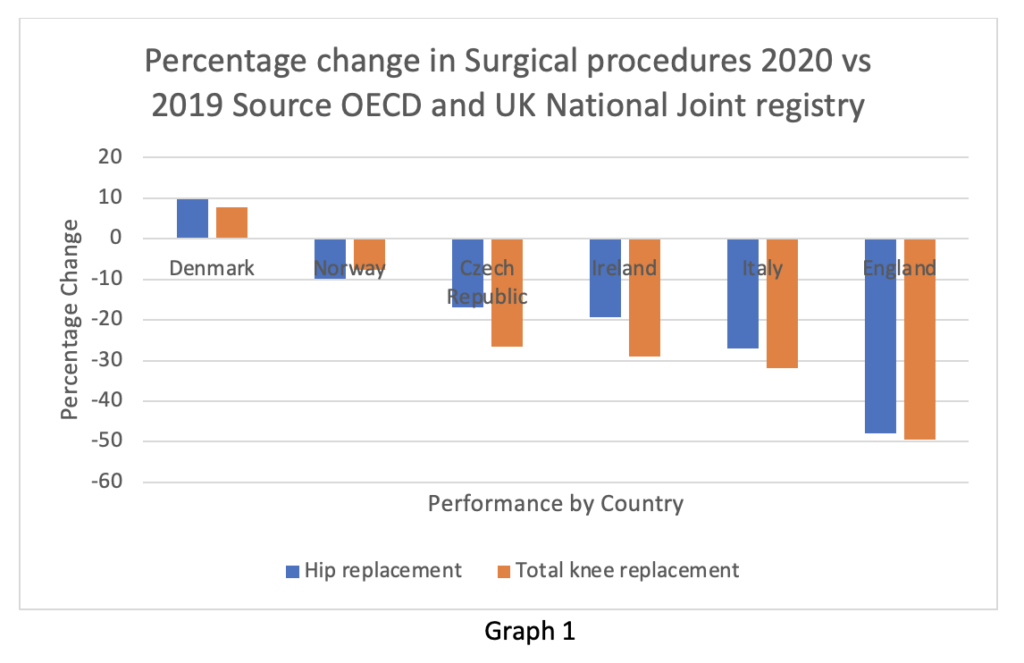

I can’t resist using at least one graphic this week. Graph 1 (reproduced from the Spectator) shows the change in procedure volume for hip and knee replacements in various European countries. The data is from 2020 and not complete, but it is a reasonable approximation of the trend. Readers may wonder why England seems to perform badly in comparison to our peers when the NHS is the envy of the world.

- Cohorting of patients: In 2020 discussions took place about how best to minimise in-hospital transmission of Covid. At the time, these were very reasonable concerns. Broadly speaking, the options split into admitting Covid patients only to specifically designated hospitals, or admitting Covid patients to all hospitals but separating them into specially controlled areas. The latter solution was preferred. Accordingly, most hospitals now have green, amber and red zones depending on the testing status of each patient. Patients testing positive for Covid while in hospital therefore need to be moved into Covid only ‘red wards’, while negative patients are in green zones and patients waiting for results in amber. When moving patients around hospital (on trips to the radiology or endoscopy department, for example), infection control protocols are mandatory. Zoning regulations play havoc with specialist nursing rotas and are in any event of questionable effectiveness in reducing in-hospital spread of Covid. With the advent of the much less dangerous Omicron variant and the knowledge that over 50% of patients have incidental Covid (plus the reasonable expectation that this percentage will continue to rise), there is a good argument for scrapping this system. Nevertheless, it will be hard to revert to normal practice any time soon, for reasons I expand on below.

- Cultural shift in relation to ‘safe working’: This metric is hard to measure, but I am convinced ‘safetyism’ is a real phenomenon. By inculcating a culture of fear in the workforce about the risk of catching Covid, friction is introduced into every facet of normal organisational function. Simply put, everything takes longer than it should because of restrictive protocols imposed by infection control departments stemming from an overabundance of caution. The ostensible and commendable purpose is to reduce the spread of in-hospital infection. The side effect is to make routine tasks like wading through treacle – everything takes longer, so fewer patients can be processed per unit of time. The overall effect is similar to throwing a handful of sand into a gearbox.

- Exploitation of ‘safe working’ by health unions: Readers will be familiar with trade unions exploiting ‘health and safety’ regulations in industries other than health. The long running dispute between the RMT union and South Western Railway about the necessity for guards on trains is one example. Arguments about provision of PPE, enhanced rest periods for staff and extended periods of sick leave do have a rational basis, but trade unions push legitimate concerns to extremes and are frequently antagonistic to management. Such behaviour exacerbates the general difficulty in returning to business as usual. The British Medical Association is frequently the most egregious transgressor in this area. Institutionally left wing, its main purpose appears to be permanent opposition to the government of the day rather than supporting coalface clinicians in delivering best medical care.

- Difficulty in discharging patients from hospital: The phenomenon of ‘bed blocking’ is well known in the NHS and the reaction to Covid has exacerbated the problem. Care homes are still licking their wounds from spring 2020 when the NHS forcibly discharged patients known to be infected with Covid into the care system. Unlike the NHS, most care homes are privately run entities, and not protected by Crown Indemnity from risk of prosecution. Not surprisingly, many homes are reluctant to take previously Covid positive patients from hospitals. Workforce shortages in the care sector, worsened by vaccination mandates, add to the problem. As a consequence, the number of ‘purple patients’ continues to mount – designated medically fit for discharge but stuck in a hospital bed. But there are still not enough of them to require housing in the temporary Nightingale facilities, which remain largely empty.

- Vaccine mandate antagonism: The mainstream papers are reporting today that the vaccine mandate for healthcare workers is about to be scrapped – if true, this is excellent news. If someone was actively trying to mess up the healthcare system, I can’t think of a better way to do it than forcing workers to take a drug they believe to be unnecessary. For clarity, I am fully vaccinated and boosted because I consider it reduces my personal risk of becoming seriously ill with Covid. On the other hand, I completely understand colleagues who take a different view. The data shows that vaccination does not prevent transmission of the virus, hence I don’t understand how vaccinated staff pose less of a risk to patients than the unvaccinated. Regardless of the data, the issue has provoked serious conflict between individuals and between staff and management in the health service, which will persist long after the argument has been resolved and the mandate binned. In a team sport like healthcare, this has profoundly adverse effects. The vaccine mandate plan will not have been conceived by politicians, but probably within the U.K. Health Security Agency. The faceless medical bureaucrats responsible for this policy really should have the courage to explain themselves in public – I won’t hold my breath.

- Long Covid: Post viral fatigue is a well-known phenomenon. It usually resolves within a few weeks. Long Covid is probably a variant of this. The symptoms attributed to ‘Long Covid’ are legion. Unfortunately, in the absence of a specific objective test for the condition, the diagnosis is purely clinical and largely made on the basis of self-reported, non-specific symptoms by the patient. A recent study from Oxford using xenon to track gas exchange in the lungs has suggested some abnormality in gas transfer in a small number of patients, but the precise mechanism and characterisation of ‘Long Covid’ remains opaque. The potential for exploitation is obvious and requires no further comment.

- Workforce ‘enthusiasm fatigue’: A grumbling workforce in the NHS is nothing new, but the last two years have worn many of the best people down. Fresh haranguing by managers to meet arbitrarily-imposed targets in the face of even more pointless regulation reinforces a sense of institutional indifference. Many employees have become demotivated and sullenly resistant, choosing to do the bare minimum rather than resign or retire. Achieving unprecedented productivity gains in these circumstances is probably unrealistic.

- Workforce shortages: Workforce shortages in critical skill sets has long been a problem in the NHS. Covid has accelerated this trend by precipitating early retirement among senior staff, incentivising career changes for those considering it anyway and encouraging some highly skilled staff such as ICU nurses to seek redeployment into less stressful specialties. I understand applications to study medicine and nursing have risen recently – attributed to the crisis inspiring young people to contribute to their communities. This is welcome, but one should point out the very long lead time between enrolling on a course and becoming an experienced clinical decision-maker (minimum 15 years in most medical specialties). I’d be surprised if the rate of new entrants compensates for the brain drain at the other end of the age spectrum.

I apologise to readers for a fairly dismal and dense piece today. I do believe these points to be an accurate summary of the challenges faced by coalface clinicians in their efforts to retrieve the situation. None of these issues will be widely aired in the mainstream media. The extent to which we ‘learn to live with Covid’ will depend not only on lifting of restrictions on wider society, but on liberating real doctors and nurses from burdensome and pointless professional regulations. Based on my prior experiences, I’m far from optimistic at this point.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Start by firing the top management.

Correction. Start by firing at the top management. Preferably with automatic weaponry.

I jest. But only slightly. Semi-automatic will do.

Start by de-extorting it.

The problem with the NHS is that what you pay for it’s “services” is not aligned with your lifestyle.

The Nazis found( that as a measure of economy ), if you stood six in a row ( one behind the other)you could take them all out with just one bullet.

‘I apologise to readers for a fairly dismal and dense piece today.’

Spot on. My thoughts exactly. Not only did this piece stand out, emphasising how good they are as a writer and what relevant subjects they always choose, but also, in such awareness, they demonstrate how much they always relate to the reader. Good, useful stuff.

“I understand applications to study medicine and nursing have risen recently – attributed to the crisis inspiring young people to contribute to their communities. ”

However obsessive rule following, closing University lecture halls to go online, pedantic mask wearing, sanitising and testing rituals that make the hospitals look lax – all to ‘send a message about professionalism’, plus excessive bureaucratic ‘absence’ processes when students are forced to isolate are putting an awful lot of them off the job.

Placements are cancelled at the last minute, or shuffled around because the NHS has less training capacity than the minscule amount it normally has, mean students are not getting the hands on training they need.

The message to medical students is that following the process is more important than the delivering a service to patients.

Unsurprisingly quite a few are reconsidering their career choices, or making plans to get out of Blighty as soon as they become medically qualified.

It would be difficult to come up with a system that is better designed to accentuate a skills crisis than the one we have.

Made the mistake at the start of the pandemic of asking my boss “I’ve had a persistent cough for x years, what do I do now”? 2 years later they still under-employ me from home and I don’t know what else I can do to go back to my NHS job. Constant shifting goalposts and they are keeping me off now for conditions they were happy for me to work with before the pandemic. What a complete sh”tshow.

If you substituted ‘chancers’ for ‘experts’, that would be closer to the truth. Casting chicken bones might have proved more accurate than their ‘models’.

When someone is consistently wrong more than by chance you have to wonder if their poor predictions were relied upon for some other hidden reason

How disappointed the “experts” must be!

I don’t yet have much experience with the NHS as a patient, fortunately.

But when I once used it, it struck me that I was the only one who seems to have kept his appointment scheduled 4 months earlier. As a consequence, the consultant arrived at 11 and left at 12 that day.

My daughter went for a minor procedure in an NHS hospital recently. She is a student at uni so for 2/5 of the year lives nowhere near the hospital. It took four appointments before we struck on one that she could actually attend – each time, she’d phone to cancel and each time they’d send out her appointment via the mail to her halls of residence (she is in her third year so hasn’t lived there for a while) and if it arrived during the holiday it would be forwarded on to her (once arriving so late that the appointment had been and gone). There was no way you could just ring up and book yourself into a suitable slot. Rinse and repeat. She’s a student so could be fairly flexible but imagine if you had to organise it around a paying job or around childcare! I used to think things were bad thirty years ago when I worked in the NHS but honestly if you had to design a booking system that cost the most amount of time and money, you would need to look no further than this frustrating waste of time and money. The sad thing is that everyone just seems to accept that this is the best that can be done. It’s shameful really.

The NHS is run for the convenience of staff, not patients.

My GP suggested I had to ‘self-refer’ for physiotherapy recently, this involves phoning a number every day at 8am hoping that you will get through to the operator before everyone else, in which case they will (apparently) call you back to find out whether you need physio or not. If you are too late, all the slots for call backs are gone and you have to try another day. I say apparently because after 4 days I gave up trying.

My mother was scheduled for cataract surgery which she had successfully but was still in the recovery phase when she received a date for bowel surgery. It was very short notice so I phoned to explain why she couldn’t have the bowel surgery. She was then sent another very short notice date which was no use. I called again and was told she was now off the list and would have to go back to her GP.

Sue Gray’s “update”, that most of the media are calling her “report”, is here.

Gray is pretending she had to leave stuff out because the police told her.

Liar! Liar!

She’ll get a peerage soon. “Baroness Gray the Liar and Shagger-Helper”.

Here’s the main point:

Cabinet Office civil servants do NOT have to follow police instructions about what they do and don’t report to the prime minister.

Gray is a liar.

Sue Gray…

She’s supposed to be a civil servant. She sounds more like a press officer in Johnson’s private office.

I have read it – it didn’t take long.

Back in the day, professionally speaking, we would have described it as “thin” in terms of its content.

It proves the point that something of the gravity of these issues should have been independently scrutinised, by someone completely outside the government machine – difficult I know but I am sure they could have found someone – and not by a member of the civil service, of which Gray states in her report that she is proud to be a part.

Phil Hyland of PJH Law did write to the Hammersmith CID team who are investigating the PM & various other members of government or civil service who have advised on the handling of the pandemic, covid jabs etc & asked that these allegations of criminal acts be added to the Crime Ref No: 6029679/21 currently under investigation. So if we are being absolutely fair, she is probably correct in what she says. Do you really want any of the Junta to get away with how they have acted whilst terrorising the citizens of the UK into compliance with their stupid & useless ‘rules’?

I sure as heck hope that the CPS agrees that prosecution is in the public interest & that the presiding judge hasn’t been bought by the Junta so that justice does prevail.

I am amazed at the contrast between the severity of handling a political party compared to the handling of someone who admitted they drove on public roads to test potentially defective eyesight.

Excellent as always, I loved this line:

“the precise mechanism and characterisation of ‘Long Covid’ remains opaque. The potential for exploitation is obvious and requires no further comment.”

Our NHS – the Envy of the Third World.

The Nominal Health Service [apologies to the author – but when you have been let down by it on what feels like more times than you have had hot dinners and had almost zero healthcare for over 2 years it is hard not to be a bit bitter]

Notional Health Service

notional

Thanks – I understand the meaning of notional – and its application to the “NHS”

I prefer ‘nominal’ – meaning “existing in name only”. Geddit?

“We are on the downslope of the Omnicon wave which has, with tiresome yet ubiquitous regularity, fallen far short of predictions by epidemiological experts.”

An interesting insider perspective. All I’d say (having the perspective of experiencing really good NHS treatment over recent years) is that there are two sets of problems :

But one thing is certainly true :

“If someone was actively trying to mess up the healthcare system, I can’t think of a better way to do it …”

… follow the money …

If someone was actively trying to mess up the health and wealth of the nation, I can’t think of a better way to do it than start an NHS”

Moderator here: if you had tried commenting a couple of minutes ago, you couldnt see that comment on the site because it was still passing through moderation. I have just approved it, you should be able to see it now. Thanks for your interest and your comment

You are right. Apologies. Please delete this comment if you think it appropriate.

Although I see and hear ‘learn to live with …..’ as it’s printed and said, my head, ever since the first time I encountered that phrase, has invariably translated it into ‘learn to live with restrictions.’ I think it’s a trick of WEF et al and their puppets.

“Learn to live with covid” first cropped up about the same time as “embrace the new normal” but at that time it was in support of the original lockdownsceptic point of view.

Yes … it seems sinister. See my above comment on supermarkets & face coverings.

Saying ‘the government expects’ is not abolishing restrictions … it’s nearly the policy of Michie the Mad Marxist.

Very true: a culture of wearing disposable gloves for everything came in when Fauci said that AIDS could be spread by casual contact, and was never rescinded. And memory fades on whether banning re-useable instruments for minor surgery came in with the BSE scare or something else, but it was still in force when I retired and probably still is.

Time, money and materials all squandered by the safety ratchet.

While agreeing with what you say about Fauci “AIDS can be caught by sharing a bottle of wine” and NHS resources squandered, I’ve had a few visits to hospital these past twelve months, mostly Day Case but also some weeks unplanned inpatient and am pleased to report that routine cleanliness and hygiene are in a different league compared to twenty years ago.

When my mum (40 years SRN Nurse) visited my dad towards the end of his unsuccessful colon cancer treatment his catheter was on the unswept and dusty floor beneath his bed.

Knowing better than to antagonize the staff she very politely mentioned to the duty nurse that this was likely to lead to infection.

The response was

“yeah well they all get infected sometime . . .”

before going to stick the catheter straight back in him although mum was able to prevent it that time.

Things had not much improved 10 years later when mum followed him into the same (rebuilt showcase hospital) see post above “cohorting patients”.

My experience recently is that cleanliness is a top priority, it happens frequently from early morning into the evening, so far as I can tell, thoroughly, taking priority over all other non medical activities on the ward.

To your other point, nurses, trainees, healthcare assistants, domestic staff &etc. all wear gloves,

Consultants and Registrars do not.

The general cleanliness thing was the result of the drug-resistant Staph aureus scare… and probably became necessary because management had been saving money by using cheap contract cleaners until it caught up with them.

That does make a difference – not so sure about gloves if proper hand-scrubbing is practised. Obviously the good old days of wiping the amputation knife on your frock coat before the next one left something to be desired…

I’d scrap the NHS and introduce a system based on lessons from Germany, Singapore, …

The NHS is so bad that the only defence you read of it is basically to say that it’s better than in the USA. That’s an awfully low bar.

I don’t see many yanks going to the UK for treatment, but I remember people starting charities to get British sick to the USA…

Usually to get experimental treatments that cost thousands of pounds hence the need to set up a charity, hundreds of people a year are made insolvent in the US because of their medical bills, none in the UK.

You could try reading a bit – why not start here?

https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/book-review-which-country-has-the

‘Lessons from Germany ‘…..hmmm …never thought I would feel uncomfortable with that again.

The new ‘NHS’ is a digital version. No more hospitals, GPs. Lockdown collected more data in order to usher in the new system. All going through Amazon and Microsoft. Nurses and doctors being got rid of down to a quarter. Goal is for this to be fully up and running by 2025.

https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/

Bit like XR then.

X stands for the extinction of the NHS. Very clever.

The new NHS will be called NHSX. It’s all explained here. https://www.bitchute.com/video/aFioCUiQlF8P/?fbclid=IwAR0fMDpX7X_oKNI568h-2bPZUu3kIL-nfS38XOUyv9zQeXziR51QnYHGAdo

NHSS more like.

Cohorting Patients.

Not obviously on topic but when my mum was recovering from a hip replacement, after 40 years as an NHS nurse, someone on the ward was diagnosed with Hospital Disease.

Mum knew a bit about infected control so was surprised when the entire ‘cohort’ was decamped to an isolated unit (not isolation, just isolated) where they nearly all duly went down with the Norovirus (or whatever) including mum who spent 2 months in conditions that she did not care to discuss subsequently.

No visitors although I was allowed to drop off domestic bits and bobs at reception and I had some contact via a fellow patients mobile phone.

Following discharge she never really recovered and barely lasted another three years but they put something else on the Death Certificate.

The similarity with Covid is that Hospital Disease was then the all consuming Rage throughout the media and any evidence of NHS culpability would be pounced upon by the media, politicians, YouTube Influencers and anyone else so it is little wonder that Managements main interest was to keep any outbreak as low key as possible regardless of the consequences to individual patients.

Boris and his inner cabal were happy to have endless parties getting pissed up in large groups on a regualr basis because they knew the virus was of next to no threat to anyone.

They unleashed the full force of the State’s propaganda machine on the British people in order to terrify us into compliance because that sense of terror could be used to justify them spending collosal sums of money on completely unnecessary covid counter measures.

The Tories used the faux state of emergency to by pass normal procurement procedures in order to direct massive amounts of money to their corporate sponsors and chums.

See Owen Paterson as an example of the corruption that took place (corruption that Boris was more than happy to excuse).

We have been ripped off by the Tories to a mind bending degree.

The most egregious aspect being that Boris has been trying to sell off access to our own bodies to pharma via the state pushed vaccines and the vaccine passport dressed up as the NHS app.

Thank you, all so bloody true.

A GP was boasting in the pub that he hadn’t had a face to face meeting with a patient for 18 months

I Wish the NHS sinecurists would get a similar delay to the pension payouts after retirement

Shameful.

And he walks off with £150K or more for doing sweet f**k all. AI can do a GP’s job much cheaper and probably with better results. Idiot GPs are heading for the dole queue.

the NHS won’t be resuming normal service

Normal “service” wasn’t sunni it was absolutely shi’ite. So gawd only knows how many unfortunate souls will be killed by the virtue signalling taxpayer-enslavers of the notional health service.

Crumbs. You can’t afford to be ill thesedays, unless you can afford to be bupa ill.

This from a third year Politics Philosophy and Economics examination at a top UK university

Question 4

When tyrants and dictators are discovered committing crimes against humanity do they

(a) Fully admit their crimes and surrender themselves to the relevant judicial authorities

(b) Lie, cheat, take part in cover ups and kill even more people in an attempt to get away with it

*85% of candidates answered (a)

Hmm…a “top” university… Are there any in G5 that offer PPE other than Oxford and the LSE?

Pleading guilty to crimes against humanity is exceptionally rare. I can’t think of any tyrants and dictators who have done it. The only person I’m aware of who has done it is Drazen Erdemovic, a low-ranking Bosnian Serb soldier, in respect of the massacre at Srebrenica.

They need re educating on the realities of life

Dominic Cummings crackup watch: he has now retweeted a message reporting the statement that “mass extinctions follow a pattern – every 27.5M years“.

This comes shortly after he told the New York Magazine that Boris Johnson was “a complete f***wit”.

This guy is cracking up. Johnson is many things, but he is not a complete f***wit. Nor is this something that Cummings is in the habit of calling his opponents. For example, he doesn’t think it was stupid to back Remain.

Anybody who thinks mass extinctions follow a pattern of happening every 27.5 million years is a loon.

I don’t often agree with Cummings, but Johnson is definitely a complete “f***wit”.

The Pig Dictators response to the Gray report is to grab more power

These are allegedly the words of Danny Mortimer, CEO of NHS Employers.

This person should tender their resignation immediately if true.

Two dispiriting experiences today …

The Lidl supermarket I visit weekly now has a notice saying [maybe not verbatim]:

‘… the government expects and recommends people to wear face coverings’.

Well sod that. They could just have settled on no notice. Judging by the number of bare faces in the store, 30% seemed to agree with me.

A Tesco supermarket I occasionally visit still has a one-way system, i.e. probably even worse.

It is your moral responsibility to go the wrong way round the Tesco. I had a surly and unnecessarily rude “team leader” there try to give me hassle, initially for not wearing a burqua (“i’m exempt”) then for going the wrong way – in her words it was about facing the same way as everyone else so for a laugh I reversed my way around, facing the same way as everyone else but heading in the opposite direction.

Tesco is a human rights serial offender. Find a local shop that wants your trade, even if it costs a bit more.

‘… the government expects and recommends people to wear face coverings’.”

Bullshit. The government is relying on its corporate stooges to do the dirty work without all that messy business of implementing laws.

Was Johnson coerced into the lockdown rules, by powers bigger than him, and was he sending subliminal messages by having gatherings that it was actually safe and he also spelled it out that the vaccine does not stop spread and does not stop infection.

The efforts to get him sacked with partygate came very shortly after his “gaffe” of accidentally telling the truth about the clot shots uselessness.

Boris Johnson on boosters – YouTube

Indeed

If it were so, then Johnson would still belong in jail. There are also many others in government and positions of power who deserve exactly the same fate.

“In normal times chronic disease management is the function of . . . GPs”.

Late last year, as reported here at DS, I spent two weeks failing to gain an appoitment with my GP despite 8 emails outlining my various deteriorating conditions. The best they could offer was a ‘consultation’ in January, on the phone.

As things worsened and only with the backing of one of my hospital specialists I got myself into EMU and two weeks either side of Christmas in the sealed specialist wing most appreciate to my needs.

I sent my GP Practice an email on Boxing Day reminding them of Spike Milligans epitaph.

“I told you I was ill’.

In my part of the world, you also have to make do with a useless telephone consultation and you get to pay the same fee you would pay if you were seen in person.

There is an age old solution to the many and persistent problems of central planning. It’s called free exchange and the the free market.

Time to scrap the NHS, give medical insurance vouchers to the public (because as a society we have accepted that everyone has a right to medical care) and let market forces put everything in its proper place.

It has worked with the airlines, with telecoms, which were awful before privatisation.

It hasn’t worked well with services that don’t lend themselves well to competition like the railways.

But healthcare is definitely susceptible to improving through market forces. The market is enormous and people could end up with several healthcare choices, which would be ideal.

Like every other (bar USA) developed world health care system, most of which outperform the UK NHS systems in most outcome measures. Just to reinforce the message, but there is no UK NHS, there are four, with very different characteristics. I am not sure all of thepoints made have equal read across or weight in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

Nice idea, but in actuality, the head of the NHS is linked to US for-profit ‘healthcare’ (hospitals in the US have been receiving a $35,000 bung for each covid case diagnosed – no conflict of interest there, no siree) so the UK will get a poor impression of the US system which is 4x the cost of other systems with a substantially poorer outcome.

Having State health care is a really bad idea as the State has a vested interest in killing you when you are old in order to save on health care, social care and pension costs.

This is one of the main purposes of the covid fraud and why Matt and Boris murdered lots of elderly with midazolam after throwing them back into the care homes and forcing DNR orders on them.

A seemingly sensible article, but I can’t really take seriously a medical professional who says at point 7 :-

For clarity, I am fully vaccinated and boosted because I consider it reduces my personal risk of becoming seriously ill with Covid.

This throw-away attitude might have been excusable in early 2021, but to still hold that view one year later suggests that our in-house doctor has lost touch with reality.

At least they are correctly identifying that they took the jab for their own safety on their own terms, and not saying they took the jab to protect patients et al. Of course there can be separate debate on whether the personal decision was properly informed and sensible.

Have I got it wrong? Wasn’t destroying the dysfunctional NHS with a fake pandemic one of the objectives of this scam to allow US Health Insurance providers and Big Pharma to move in and make a killing? Will GAVI be far behind?

Isn’t this what ‘Globalist Corporatism’ and Billionaire Rule is all about?

I would say the NHSas I support Doctors and Nurses who decline a supposed vaccine still in trial till 2023 , I am someone who has not much dealing with the NHS as I try to eat a healthy diet lean protein vegetables fruits seeds and do some daily exercise walking spinning running yoga about four times a week aside daily blood pressure weight , and annual health checkup spream tests I get every six months .

but I can say no healthcare system is the world leaves people 17 hours for seeing someone concerning cancer ,hip replacements .

I had this myself at St Ann’s hospital I waited from 2:00pm till about 9pm this was in 2013 for about 10 hours to speak to a mental health doctor prescribed by my GP, concerning mental anxiety I have very badly since 2008 getting bad as mask wearing is still 90 percent, where I live and people wear them in the street alone in their cars.

As for my dentist a NHS practitioner some private dental work Veneers, and I just had a appointment today first time in 23 months the dentist’s were all masked my dentist masked and wearing a face shield I had my teeth looked at and cleaned and washed as for appointments for concerns my local GP practice will only allow you to book a appointment on the day not four or five days or a week in advance to see them .

I think a conversation needs to be had how can we going forward having a health care service which is knowledgeable about food health advice , and not so keen to just treat a disease which kills the obese elderly , like Covid-19 a real disease which has killed some people mostly with , and also not just giving harmful fake vaccine boosters to young thin people who did not need a third or second jab the NHS seems mostly keen to jab everyone in sight without caring about infertility and legs swelling up and possible bad side effects,

it needs to be revamped and these manger directors need to stop being paid about 70,000 a year for sitting at home not seeing or refusing to treat cancer it certainly does not need more investment or tax payers to pay more for a failing health service which had about 30 million put in it by our Tyrannical Government so they can’t ever cope they say can’t cope with that amount of people invested in them , should be defunded or privatised .

The managers will be getting much more than £70K. A good saving would be to sack the lot of them and any also doctors who still believe that Covid is a good excuse for sitting on their backsides and twiddling their thumbs, while patients go untreated.

The UK system has more managers than beds, probably substantially more following Khunt’s Kruelist Kuts.

The NHS also have become a religion as now people do not worship god or church instead the fat overweight don’t eat vegetables fruits nuts seeds worship it so do some people I know who only used it to give birth, I ask why is the NHS so wonderful at work sure some Health care systems might not be as good America private cannot afford health care do not get any or on state benefits do not get seen .

I just think the NHS cannot be criticised for it faults most people I know especially briefly not friends from College just people at work mostly aged 50 plus defend it the ones who never saw their mother for 18 Months had those virtual signalling signs Rainbows on the Wall watched the BBC daily they just say it is Wonderful for no reason no opinion of the bad side of the NHS long waiting hours the Liverpool pathway neglect of the elderly in care homes and hospitals , the campaign of terror they went a long with the government some including one doctor on the NHS in January 2021 Montgomery said people who do not wear masks have blood on their hands .

The NHS must also prepare for the mental health pandemic and all the people neglected with cancer , who died last summer not being seen due to their neglect as they only treat Covid no other Heath ailments, as they were suppose too ,

I think some doctors nurses work hard and do excellent jobs but they are not angels just workers doing a harder job then most good article though .

I just had to call an ambulance for an old gentleman with Parkinson’s who fell over on a poorly lit, rough pavement outside.

He had smashed his chin, tooth and hand quite badly.

The call handler was from a national based call centre and more worried about had myself or the patient had the big C in the last few days or come into contact with anyone who had….

I didn’t want to spoil the fun by telling them I’m not vaccinated, not once wore a mask, never taken a test but here I am covered in a pensioner’s blood at nearly midnight in the freezing cold.

To top it all off….a quoted up to TWELVE hour wait for an Ambulance.

Luckily another neighbor helped me lift the gentleman into a car and he was not seriously hurt and we got him to his house.

Still no sign of the emergency services. I’m lucky to be back home in bed unharmed but this experience has taught me that the NHS should be ashamed of what it has become.

The list often is almost identical to the list of NHS problems I created in 2018 for my book “Mad Medicine”. I retired from the NHS 11 years ago. Nothing has changed. And indeed nothing has really changed since 1948 in terms of pressures on the service because medicine has been able to do more and more at ever greater cost. Reorganisation has occurred on numerous occasions and has never solved the underlying problems. If you want a system that can always cope you need to build in slack time redundancy; a bed occupancy of over 85% creates problems but to keep it below that at busy times requires a normal occupancy of 60% or less. So you have to decide whether to be economically efficient and run the risk of being overwhelmed at busy times, or inefficient and expensive. Successive governments have chosen the latter.

I have encountered good and bad managers but even the most brilliant cannot run a bankrupt business, so firing them merely means you bring in new people who still won’t cope, not least because they don’t know the business.

I believe that COVID is only a blip. The underlying problems of the NHS will still be there when COVID is gone.

Of course it won’t return to normal anytime soon. It was never intended to. The plandemic was engineered in order to deconstruct the NHS and bring in the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation backed digital NHSX. Gates proudly boasted that by 2025, ‘doctors will be no more needed than car mechanics’. We already know that bringing in electric cars is the first step in preventing car ownership, meaning car mechanics ultimately will be redundant. So what is the plan, in only 3 years, to similarly make doctors unnecessary? I hope Deagel’s population forecast for 2025 for the UK – only 14 million – isn’t about to come true!

If it was all about undermining and undoing the NHS, why are so many other countries involved in the same agenda with the same harms inflicted on their populations? The agenda being played out is more than solely targeting health systems.

Why do people feel the need to declare their vaxx status. It removes validity to their discussion on all issues covid. It is obvious the vaxxes, simply do not work. Negative efficacy abounds. And yet medically educated people insist on telling us they took the vaxx for whatever reasons? As far as I can tell all common and scientific sense is thrown right out the window.

GPs are never coming back. The NHS gatekeepers will be gestapo-trained receptionist and AIs. All part of the plan. You will die at the end of your working life, and you will be happy.

Very revealing article. However I have been learning recently of an even bigger and long standing problem for the NHS. It’s what’s being described as the covert dismantling of the NHS into the hands of big American corporations. Dr Paul Hobday & Dr Bob Gill explain it well, as did John Pilger in his 2019 documentary “The dirty war on the NHS”. And also look out for the Health & Care Act coming our way in the summer. It doesn’t sound like good news.

The US corporates want rid of the universal coverage aspect. They just want to be able to select the most profitable cases for ‘treatment’.

Thanks for the honesty. I had Hartmanns procedure in December 2020 as an emergency y and was told I’d need to wait for a reversal for 9 months. In December 2021 I was told it would be 2 years. The nearest private hospital fir this is either 200 or 400 miles away. I am lucky- I’m totally back to normal, but I will now be at least 77 if the op is done then. Yes, I can open perfectly well and understand the backlog of people far far worse than I, but it is nevertheless frustrating when I read articles like this

Patients testing positive?

I think I see part of the problem there.

Perhaps the NHS could provide proof of asymptomatic transmission from ostensibly healthy individuals. Just one measly fully documented case arising in the hundreds of thousands of case on record. Just one will do.

Medical clinics and hospitals in USA are denying life-saving Ivermectin medicine even with court orders. Big Pharma doing all that they can to push the vaxx and inoculate us while effective and cheap COVID cures exist. There turns out to be censorship that we have never seen before for those who are looking for these treatments. We say over and over again that indepenedent researchers found Ivermectin safe and very effective for these Flu-Corona symptoms. Getting Ivermectin is easy https://ivmpharmacy.com