In an unfortunate piece of timing for the Prime Minister, who on Tuesday told the nation that vaccines aren’t helping cut infections (which is a funny way of encouraging people to get one), on Wednesday a new study appeared from NHS England and the University of Manchester that reassuringly confirmed the vaccines do in fact appear to be highly effective. The Telegraph summarised the findings.

New research from NHS England and the University of Manchester showed the stark difference in cases, admissions and deaths for elderly people who had been vaccinated compared to those who had not.

In a large study involving more than 170,000 people, researchers had scrupulously case-matched participants to make sure the results were not skewed by underlying conditions, sex or geographical location.

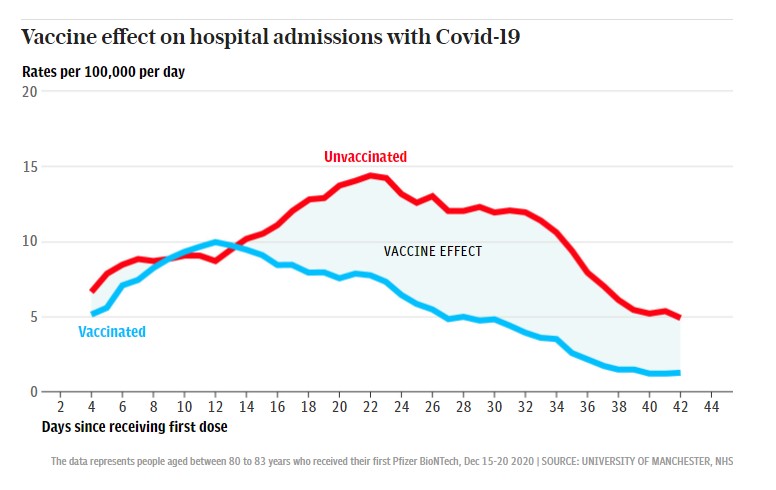

The results show that far from having little impact, the rate of Covid-related hospital admissions fell by 75% in vaccinated 80 to 83 year-olds within 35 to 41 days of their first dose of the Pfizer jab. The rate of people getting Covid dropped by 70%, with the number of positive tests falling from 15.3 per 100,000 people to 4.6. …

The figures also suggest the link between infections and admissions has also been broken by the vaccine programme.

While nearly 40% of unvaccinated people who were infected ended up in hospital, only 32% of the vaccinated cohort did.

This is encouraging, and with antibody levels in the country running at 55% at the end of March, and levels highest in older people, it is not surprising to hear this is having an impact on infections.

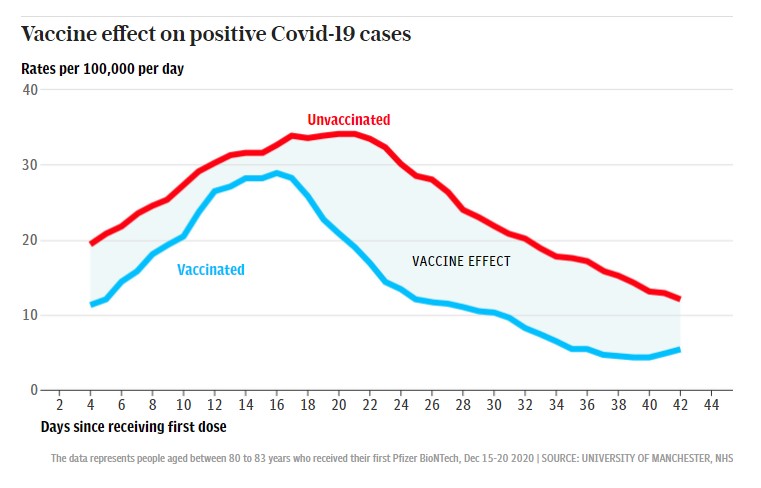

However, what I find frustrating about studies like this one is that there are some glaring problems that most people, including the authors, seem content just to gloss over. Look at those graphs above. Isn’t there something obviously wrong with them? Look at the left hand side. The lines don’t start from the same place. The unvaccinated control group starts (on day 4) with much higher incidence, even though that is way before the vaccine is supposed to have any effect (the researchers agree on this point – they keep vaccinated people in the unvaccinated control group until 14 days after the jab).

The researchers say they have checked that the two groups do not have different levels of exposure risk (and include a graph to prove it). But why then at the start do the unvaccinated appear to have twice the rate of positive cases? If we were to normalise both curves to start at the same point, the size of the “vaccine effect” would be considerably reduced. There is also the oddity of the vaccinated group appearing to be starting an upturn in cases after day 40.

A second noteworthy point is that there is a spike in Covid infections in the two weeks following the first jab. So pronounced is it in the hospitalisations graph that for several days the vaccinated are hospitalised at a greater rate than the unvaccinated, even though they start at a lower rate. This post-vaccination infection spike has been observed in almost all of the vaccine studies to date, particularly with the Pfizer vaccine, as Dr Clare Craig has noted in the BMJ. One unanswered question in this study is how this spike may have affected the incidence in the control group if people were being kept in that group until 14 days after being vaccinated – was it elevating it?

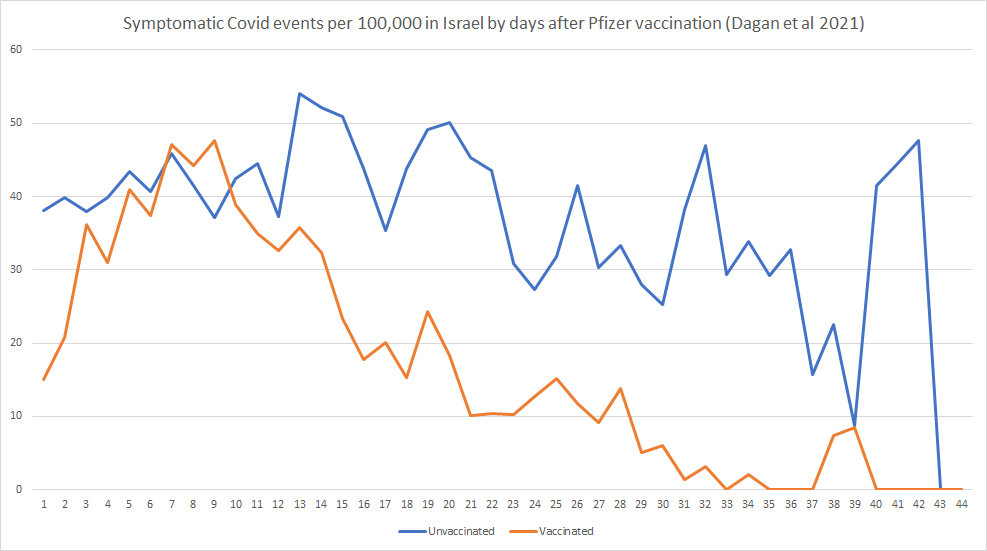

This is not the only recent study to have issues like these. Another one (which also shows the vaccines being highly effective) is the large population study in Israel that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine at the end of February. This one provides its full data tables so we can see exactly how Covid incidence changed over the study period. Below is the incidence of symptomatic Covid infections per 100,000 people by days since Pfizer vaccination (note that by the last few days of the study very few were left in it owing to most of the people in the control group having been vaccinated, making the data noisy).

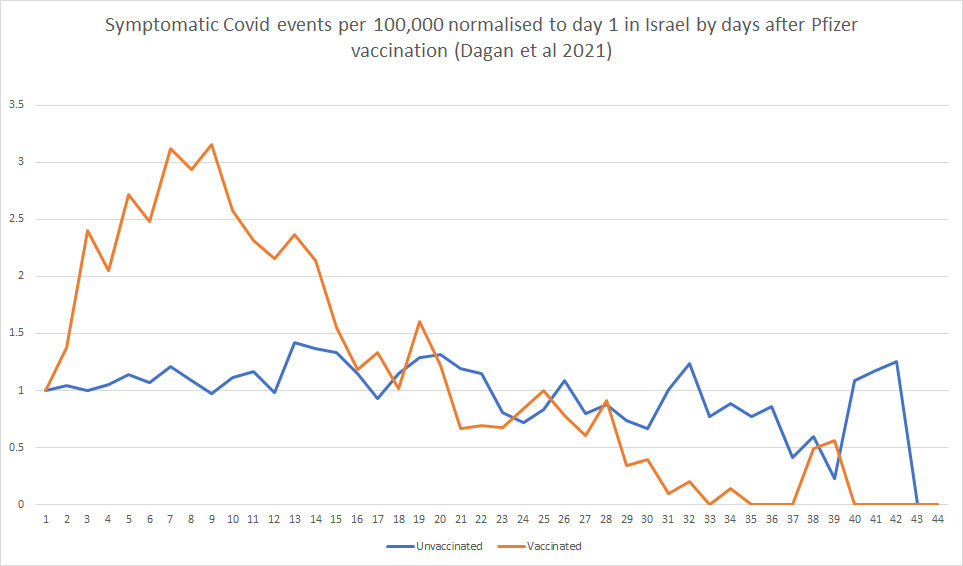

Again we see infections in the vaccinated group dropping much faster than in the unvaccinated group, confirming that the vaccines appear to be working. But once again, look at the left hand side. Why are infections in the vaccinated group starting at so much lower incidence than the unvaccinated group? In this case, because we have the raw figures, we can normalise the curves to day 1 so we can compare how they are changing relative to where they begin. The result is shown below.

Infections in the vaccinated group, unlike in the unvaccinated group, drop quickly to very low levels after day 28, which is a week after the second dose and so fits well with when the protection is expected to kick in. This is certainly encouraging. However, look at that spike in infections during the two weeks post-vaccination – it’s huge.

I’m not trying to do the vaccines down here. I have no wish either to big them up or to see them fail (in fact, I want them to work and be safe). I just want to know the facts about them, not least so that confidence in medicine and vaccines in general can be maintained. Which is what makes studies like these so frustrating. They claim to show high efficacy for the vaccines, and certainly the data is impressive. But then they have these odd unexplained features – different starting points, big spikes – that make you wonder if you’re being told the full story.

There has been a worrying new theme in the past week or so of world leaders appearing to downplay the efficacy of the vaccines. On Monday, the WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom said:

Several countries in Asia and the Middle East have seen large increases in cases. This is despite the fact that more than 780 million doses of vaccine have now been administered globally. Make no mistake, vaccines are a vital and powerful tool. But they are not the only tool. We say this day after day, week after week. And we will keep saying it. Physical distancing works. Masks work. Hand hygiene works. Ventilation works. Surveillance, testing, contact tracing, isolation, supportive quarantine and compassionate care – they all work to stop infections and save lives.

Canadian PM Justin Trudeau on Tuesday told Canadians that vaccines aren’t enough to end mask mandates and social distancing restrictions. The same day, Australian Health Minister Greg Hunt said:

Vaccination alone is no guarantee that you can open up. If the whole country were vaccinated, you couldn’t just open the borders. We still have to look at a series of different factors: transmission, longevity [of vaccine protection] and the global impact – and those are factors which the world is learning about.

The reference here to what “the world” is learning and the fact that the governments of Canada, Australia and the UK all gave out a similar message the day after the WHO chief said the same thing suggest to me that something may be shifting behind the scenes internationally in terms of how far vaccines are understood to allow things to return to normal.

Do they know something we don’t? Perhaps they are concerned about some of the data on how the vaccines fare against new variants. An NEJM study from March found that the AstraZeneca vaccine was only 10.4% effective against the South African variant. Is this why the UK Government is so concerned about the outbreak in Wandsworth and Lambeth?

Another potential concern is the weak T cell response from the vaccines. New research has shown that only 31% and 12% respectively of people who received the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines developed T cells against the virus spike protein. With antibodies (whether from infection or vaccination) known to fade over a period of months (which is possibly showing up already in the ONS antibody survey, with a surprise drop in the antibody levels in the over-70s in the latest data), the weak T cell response would seem to bode ill for long term vaccine protection.

The lockdown sceptic argument has never rested on the arrival of vaccines. Safe and effective vaccines are welcome – though people should never be coerced into having them or basic freedoms made dependent on them. South Africa is notably faring well at the moment, despite being dominated by the South African variant (and having done almost no vaccinations). The sceptical argument, rather, is based on a cool-headed, scientific cost-benefit analysis of the gains and harms of imposing restrictions on the population in the face of a viral threat.

Ministers claimed until recently they would end the state of emergency and return things to normal when the vulnerable were vaccinated, and we took them at their word. Increasingly it seems that was, predictably enough, a mistake.

If the Government still has confidence in the vaccines then it needs to begin acting like it and bring the emergency to an end. If it doesn’t then it needs to be upfront about this so a proper debate can be had about what that means for the future. As it is, it feels like big decisions about how life is going to be lived from now on are being made behind closed doors without proper input from a wide range of voices and proper scrutiny of the data. What remains of our free and liberal country deserves better than this.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.