There follows a guest post from our in-house doctor, formerly a senior medic in the NHS, on what we know so far about the Omicron Covid variant. He’s also written about the scandal of the Downing Street parties – Secret Santa-Gate – asking: “If Covid really was such a mortal threat as the Government have led the public to believe, do readers really think that Downing Street apparatchiks would be flocking to packed parties in small rooms? I suspect not.“

It’s now two weeks since the world first heard of the Omicron variant. Travel restrictions and mask mandates were immediately reimposed on the U.K. population and have since been tightened further. Reports in the press this morning are trailing the reimposition of more curbs on liberty in the U.K. over the next few weeks. In today’s update, I will examine what we have learnt about the new variant and to what extent it may affect the situation in the NHS. This update is a bit data-heavy, so apologies in advance for the graphic fest.

South Africa is widely regarded as the epicentre of Omicron. Having spent considerable time working in that wonderful country, I can attest to the expertise of my South African medical colleagues, particularly in the field of infectious diseases. So, when Dr. Fareed Abdullah writes from the Steve Biko Hospital in Pretoria that the data so far on the Omicron variant suggests it is very much milder than the Delta variant, I’m inclined to take him seriously.

I encourage readers to examine this document themselves – this extract is worth quoting in full:

In summary, the first impression on examination of the 166 patients admitted since the Omicron variant made an appearance, together with the snapshot of the clinical profile of 42 patients currently in the Covid wards at the SBAH/TDH complex, is that the majority of hospital admissions are for diagnoses unrelated to Covid. The SARS-CoV-2 positivity is an incidental finding in these patients and is largely driven by hospital policy requiring testing of all patients requiring admission to the hospital.

Using the proportion of patients on room air as a marker for incidental Covid admission as opposed to severe Covid (pneumonia), 66% of patients at the SBAH/TDH complex are incidental Covid admissions. This very unusual picture is also occurring at other hospitals in Gauteng. On December 3rd, Helen Joseph Hospital had 37 patients in the Covid wards of whom 31 were on room air (83%); and the Dr. George Mukhari Academic Hospital had 80 patients of which 14 were on supplemental oxygen and one on a ventilator (81% on room air).

Dr. Richard Friedland, Chief Executive of Netcare (the largest private hospital group in South Africa), has been reported this week as saying Omicron infections are not causing a significant increase in hospitalisations and that the Omicron wave can be dealt with in primary care if this trend continues.

The E.U., the WHO and Dr. Anthony Fauci in the U.S. have all made reassuring statements to the effect that Omicron so far appears to cause mild symptoms and little in the way of hospitalisations.

So far, so encouraging. I was expecting more hard information at the Downing Street press conference on December 8th from the Chief Medical Officer. “Alas, it was with a heavy heart” that I found myself disappointed. Professor Whitty did refer to anecdotal information from South Africa that “hospitalisations have risen by 300%” but provided no source for his assertion. I have looked around and can’t find that published anywhere. I have asked South African friends for their views. My anecdotal information reports that South Africa currently has 500 serious Covid cases in hospital across the nation and the health system is well on top of the situation. Anecdote is frequently unreliable as a means of assessment – I will return to this point later in the piece.

The Prime Minister made reference to the “remorseless logic of exponential growth”, as did the Chief Medical Officer and Chief Scientific Officer with graphs of a steep upturn in Omicron variant cases tested in the U.K. At no point was any reference made to how many of the 560 cases identified to that date in the U.K. had ended up in hospital, nor any information as to how many people in South Africa have died as a direct consequence of Omicron infection – my informants tell me no-one has so far been recorded of dying from Omicron infection by the WHO.

Comments were made in relation to the fact that the South African population is a younger demographic than that of the U.K. and therefore we may be more vulnerable to the variant. This is a reasonable point. I must have missed the counterargument that the vast majority of the South African population are unvaccinated and they also have the highest incidence of HIV in the world, both factors which may render their people more vulnerable to Covid infection than those in the U.K.

There were no remarks at the press conference as to how the modellers have varied their predictions to take into account Omicron encountering a population with a degree of prior familiarity with Covid and a high vaccination rate. It is reasonable to worry that Omicron may exhibit a degree of vaccine evasion and be able to reinfect people who have previously had Covid. But it is not sensible to assume the effect of Omicron will be similar to the first or second wave of Covid, when the virus was invading a completely immunologically naïve population. The track record of the epidemiological modelling community over the last 18 months hardly inspires confidence – on every previous occasion when their hypotheses have been tested against real-world data, the predictions have been huge overestimates. I have often recalled the comment of the great economist J.K. Galbraith to the effect that the only function of economic predictions was “to make astrology look respectable”.

I should make it clear that Omicron could spring a surprise and create another wave of serious disease – that is a possibility, although the data so far suggest otherwise. The press conference on December 8th provided speculation rather than facts in support of a worst-case hypothesis. As Steve Baker MP said in the House of Commons on December 9th, “We are taking away the public’s right to choose what they do based on flimsy and uncertain evidence.” It is disappointing that the Chief Medical Officer, with all the machinery of state at his disposal, can present less of an update to the public than I can with a laptop and a couple of hours of research.

Next, I turn to the current situation to assess whether the NHS is in imminent danger of being overwhelmed by a wave of new Omicron hospitalisations.

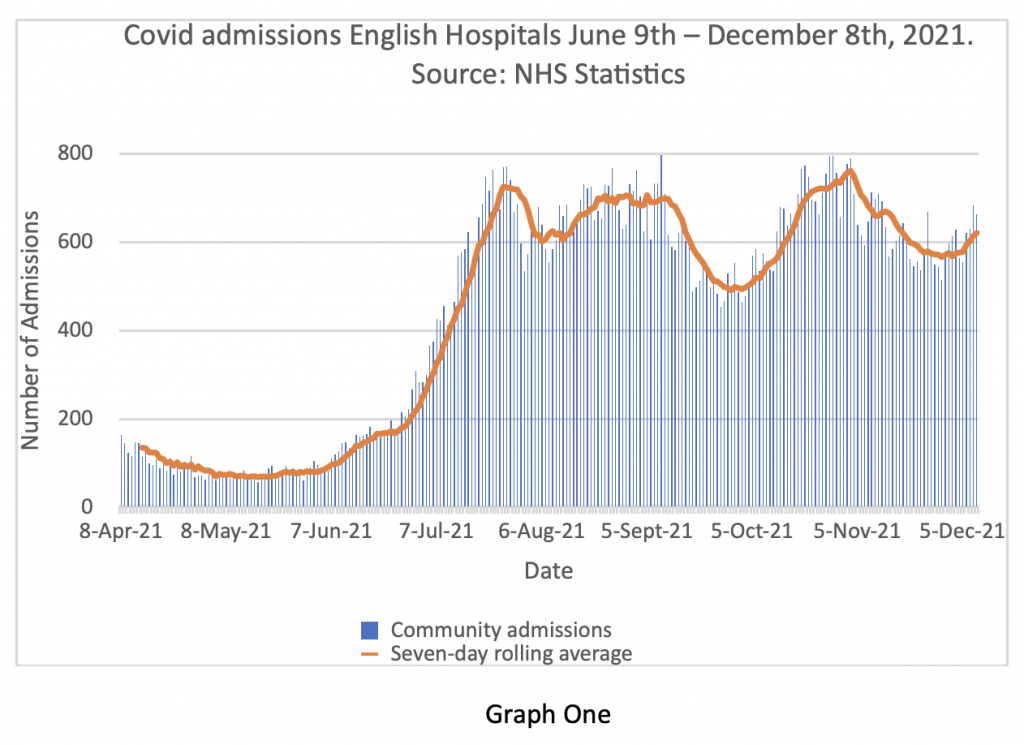

Graph One shows the updated Covid admissions to English hospitals. There is a suggestion of a slight upswing in admissions on the seven-day moving average at the right-hand side of the graph, but so far no major change and daily admissions are at a lower level than they were in July and August.

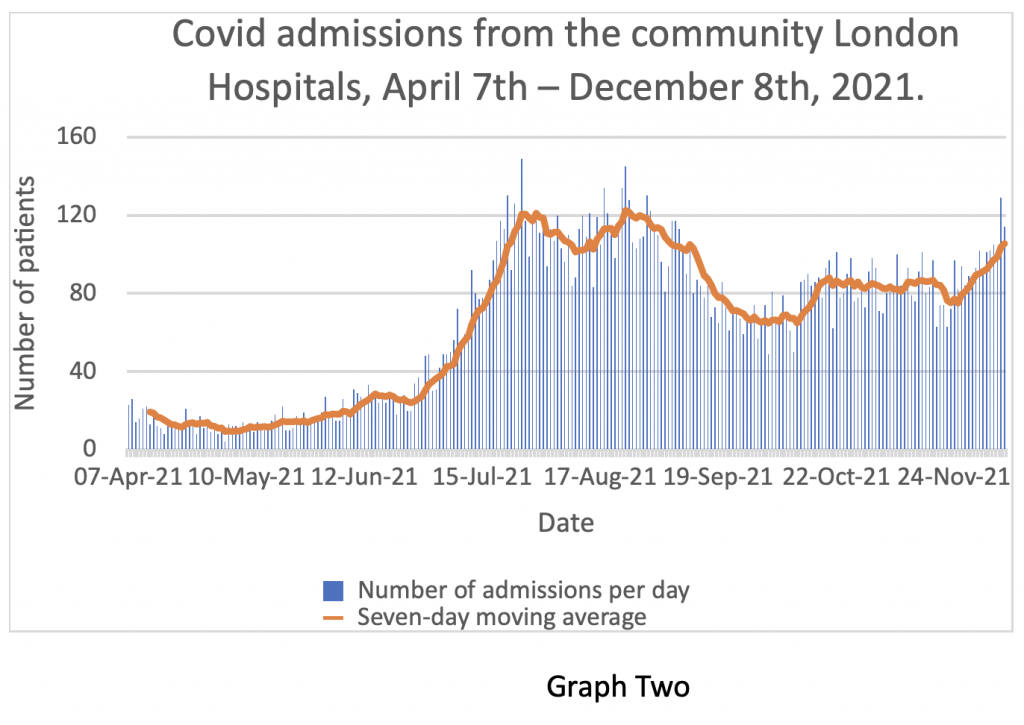

Yesterday, Michael Gove said that 30% of Covid infections in London were Omicron cases, which seems to be the front running Omicron region in the U.K. Accordingly, I have selected out the data on Covid admissions to hospital from the community in London in Graph Two. There has been an increase in admissions over the last week, but it is still below the level in July and August. It is as yet unclear whether this increase is an expected seasonal uptick, or due to the Omicron variant. I have not seen any information released to date around what proportion of recent admissions are Omicron as compared to the dominant Delta variant. It should also be noted that the daily numbers of patients are increasing from a low base – currently running at about 100 per day in the capital.

As I write this piece, the ‘experts’ from the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene are confidently predicting that Omicron will cause 2,000 hospital admissions per day and 24,700 deaths between December 1st and April 30th, 2022. I turn again to Professor Galbraith who observed in relation to economic matters “there are two kinds of forecasters – those who don’t know; and those who don’t know they don’t know”.

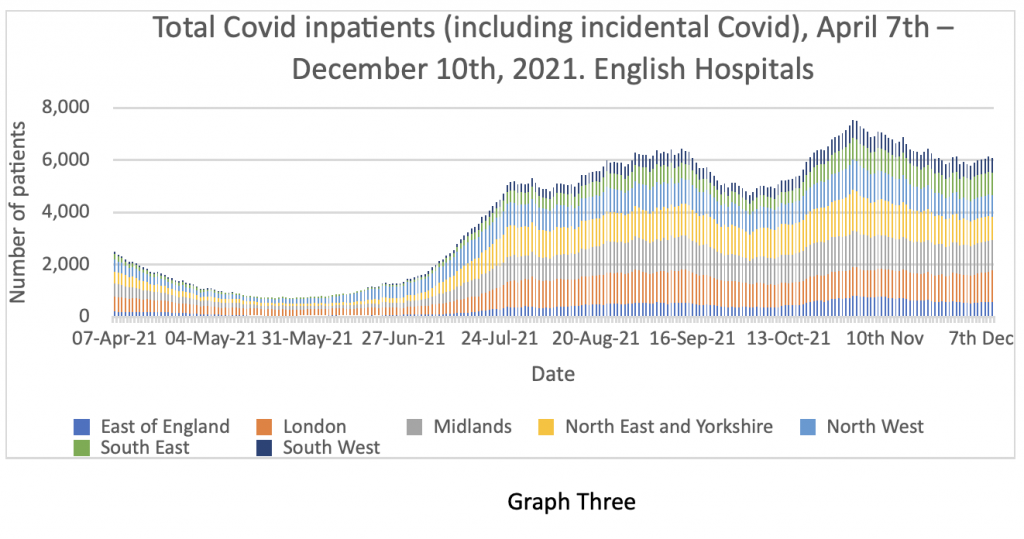

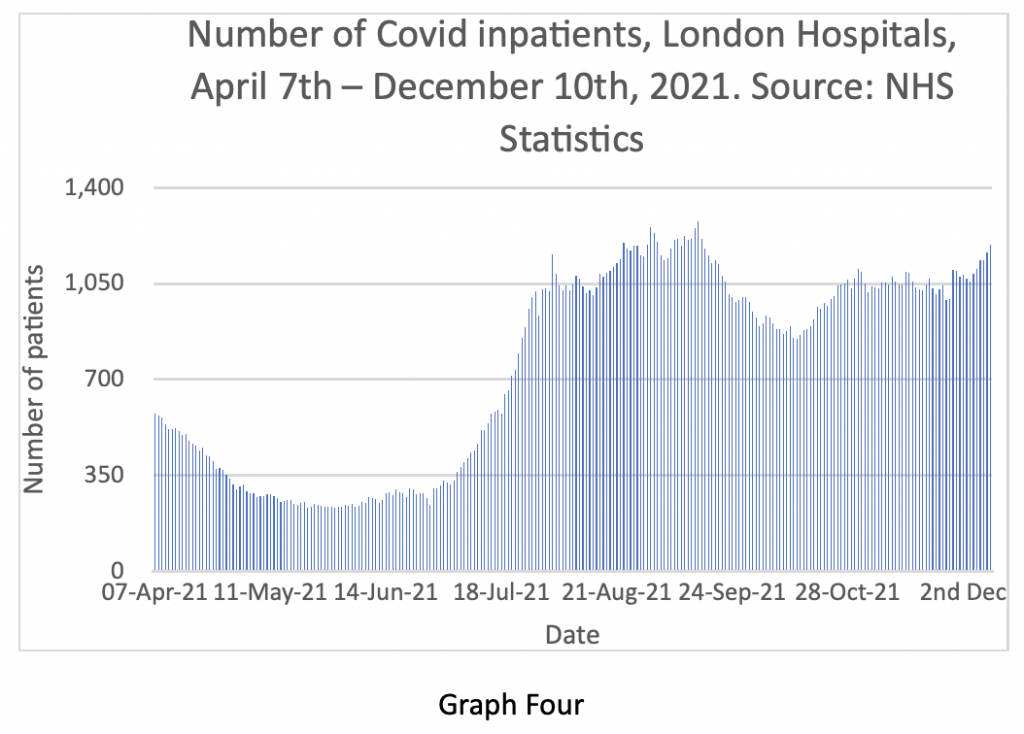

Next, overall Covid hospital patients in Graph Three and the equivalent data from London alone in Graph Four. Overall, in England, there is no discernable rise in inpatient numbers. It should be noted that these graphs and the headline figure of 6,000 inpatients are an overestimate of the numbers of patients being treated for acute Covid. The primary diagnosis data continues to show that only 75% of these patients are hospitalised with acute Covid – the other 25% are being treated for something else. Further, this week it was reported by the Telegraph that their source inside NHS England (referred to as ‘George’ on the Planet Normal podcast) has revealed that about 10% of the patients classified as Covid inpatients have in fact recovered fully and are stuck in hospital because they cannot be safely discharged to care homes. This so-called ‘bed blocking’ is a regular feature every winter but may have been exacerbated this year by the vaccination mandate for care home workers reducing the workforce. If ‘George’ can be believed, therefore, the correct figure for inpatients being treated for acute Covid in English hospitals is closer to 3,900 than 6,000.

Graph Four shows the inpatient figures for London. Again, there is a slight uptick at the right-hand side of the graph mirroring the admissions data in Graph Two. It is not yet possible to comment on the significance of this in relation to the Omicron variant as the information has not been provided.

Before turning to Intensive care matters, I thought it would be instructive to draw readers attention to the current situation around influenza. The U.K. Health Security Agency flu surveillance report for week 49 states: “Influenza positivity remained very low at 0.7% in week 48. Other indicators for influenza such as hospital admissions and GP influenza-like illness consultation rates remain very low.” To put that figure of 0.7% into context, the percentage of positive influenza tests at the same date in 2019 was 17%. On October 14th, 2021, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Jonathan Van-Tam told the British Medical Journal: “Not many people got flu last year because of Covid restrictions, so there isn’t as much natural immunity in our communities as usual. We will see flu circulate this winter; it might be higher than usual, and that makes it a significant public health concern.” So far there is absolutely no sign of flu for the second year running.

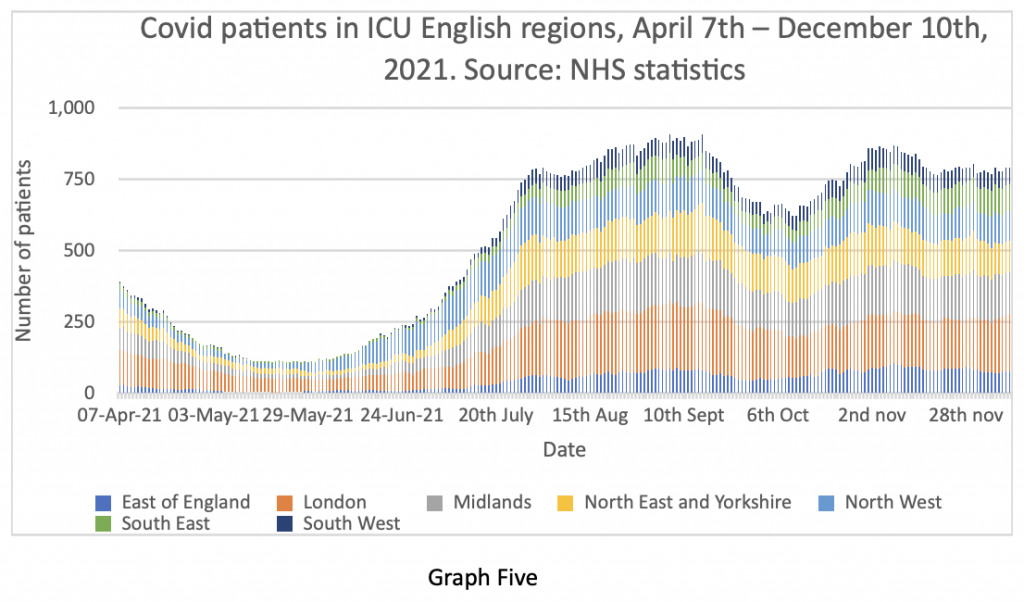

The intensive care information this week is interesting. Not so much for the data presented in Graph Five, which is fairly flat, but for the data in the weekly ICNARC national audit report around percentages of vaccinated vs unvaccinated patients in ICU.

I have been puzzled for months about why the information in relation to the vaccination status of ICU patients has not been included in the ICNARC updates. Two weeks ago, a tranche of data was released showing that 75% of patients in ICU were unvaccinated. However, although widely and rapidly commented on in the press, the statistics only covered the period from May 1st to July 31st.

This week ICNARC provided more information up to November 14th. The link to the report is here, and the relevant information about vaccination status is on pages 44-46.

In summary, the report finds that 48% of patients currently in ICU are unvaccinated, down from 75% in July. This surprised me because my anecdotal information had led me to believe the percentage of unvaccinated patients in ICU was higher. ICNARC make the reasonable point that the relative increase in the percentage of vaccinated patients in ICU compared to the unvaccinated mirrors the general increase in vaccination uptake in the population as a whole. Furthermore, it is important to recognise that vaccinated people needing ICU care for acute Covid are rarely healthy individuals to start with – the vast majority of vaccinated Covid patients in ICU have major risk factors – the principal ones being advanced age and obesity. It is also possible that in the older cohort some vaccinated patients may have suffered from waning vaccine immunity, having been jabbed early in the year and not yet had a third booster dose.

Based on these figures, if one assumed the entire U.K. population was vaccinated, we would still have about 500 severely ill people in ICU with Covid compared to the current 800 cases. As a comparator, in a bad flu season, there are frequently similar numbers of patients needing critical care in the U.K.

It was disappointing not to see any information in the report on outcomes in relation to vaccinated vs unvaccinated patients, but ICNARC is a superb audit organisation and they will probably get around to analysing this point in due course.

I have been perplexed and troubled by some medical colleagues making disparaging remarks about unvaccinated people in ICU – sometimes verging on suggesting that unvaccinated people should not be given ICU care should they fall ill with Covid. For the sake of clarity, I should make it clear my reading of the data suggests vaccination is highly protective against severe illness and death from Covid in all age groups over 50 and probably substantially beneficial in the over-40s. I personally have had both the standard two doses and a booster. Nevertheless, if some people don’t wish to be vaccinated, that is their right and a valid choice which should under no circumstances affect their future care. All doctors registered in the U.K. are obliged to undergo mandatory training every two years in relation to consent to medical treatment and the capacity of patients to make choices. Capacity is very important in this regard. Even a patient with advanced dementia has capacity to chose what type of treatment they wish to have and what they do not consent to. A doctors duty is to guide, advise and interpret treatment options for patients – not under any circumstances to coerce people down a particular treatment pathway. If a person over 40 wishes not to be vaccinated against Covid, I personally think that is an unwise decision, but it should not affect that individual’s access to medical care in any way, nor should they be stigmatised or vilified for making that choice.

Finally, the Downing Street party affair. Despite this not being a directly medical matter I do think it has some bearing on the overall situation. Besides, just about everyone else in the country has expressed a view and I don’t want to be left out. The asymmetry of rule setting versus rule observance concerns me less than what the incident tells us about the real risks of Covid.

The state functionaries tasked with terrifying the nation into subservience quite clearly do not believe their own message. There is a dissonance between what they say and what they do. Put simply, if Covid really was as great a mortal threat as the Government has led the public to believe, do readers really think that Downing Street apparatchiks would be flocking to packed parties in small rooms? I suspect not.

Consider also that this behaviour was taking place in December 2020 – when the vaccination programme had not even started. The incident reveals that the people disseminating ‘project fear’ knew and still know that Covid poses minimal risk to the majority of the population (and even less now we have a high vaccination uptake). As to what happens in the coming weeks in relation to Omicron, I am sticking with Professor Galbraith – I have no idea but will keep an eye on it and update as we go.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The CIA from the 60s had journalists planted in every major newspaper across America. Of course, they still do.

They had made somewhat of an art form of getting rid of annoying Presidents, domestic and foreign, but 1963 was messy. Nixon needed to go. Watergate achieved that.

Nixon hated the clandestine hitmen of the CIA, and could only bring himself to talk about Kennedy’s assassination as ‘the Bay of Pigs thing’. E Howard Hunt was one of the burglars, a nasty piece of CIA work present at Dallas by coincidence, and claimed he was one of the assassins. These CIA operatives were doing Nixon’s dirty work. Apparently. So we are told.

Not sure I believe any of these ‘pat’ narratives anymore.

I remember the sheer mind melting complexity of it. The Byzantine impenetrability of the story/stories. It was a maze, a labyrinth. Not unlike crazy Covid narrative and how that was spun and is now being unspun for the unthinking by intelligence led MSM.

Bernstein and Woodward. Honest brokers? Who knows? Maybe it needs a lot more reevaluation. We were a lot more naive then.

Big events are planned / executed / and then managed. Spinning the story is done by managed journalists. We remember Nixon’s paranoia. We tend to forget Harold Wilson’s. Where did the paranoia go?

you would not call those people ‘journalists’, an actual ‘journalist’ is someone who seeks out what is really going on, and reports that truthfully – there has been pretty much zero of that the last few years – these people are hacks and propagandists and various other things decent people don’t really want to associate with

Strange but true, Nixon was America’s most popular president of all time!

Were they not lefties? If I’m right, they would be cheerleading the whole thing. Unless someone thinks they were interested in the truth for its own sake and not just so they could discredit a Republican?

If this is true: https://www.gbnews.com/news/whatsapp-could-soon-be-illegal-in-uk-warns-its-horrified-boss-it-s-a-bad-thing it could be exploited by the Gov to make it more difficult to learn the truth.

‘Where are the Bernsteins and Woodwards of COVID-19?’

A question I can answer.

Bullied, silenced, cancelled, fired.

Or willingly complicit.

I am not usually a fan of Dr Alexander’s ruminations on the current scene but I think this article is on the money.

By and large main stream journalists failed and badly. The net result has been a disaster for the country.

For those journalists who declined to do their jobs there is no way back, they will remain the whores of the Reset, not on their own certainly but definitely at the front of the pack alongside the irredeemable $cientists and medics.

The best book on Covid was actually written 183 years before Covid started. It’s by a Danish guy Hans Christian Anderson and was called “The Emperors New Clothes”.

It’s an analogy of a very real, and very deadly mind virus called Mass Psychosis. That illness allows large groups of people to become convinced that a delusion is actually real.

There’s also another book well worth reading called “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds”, published in 1841 by Charles Mackay.

His most famous (and prescient quote) was:

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one”

Whitty and Vallance knew that the virus wasn’t serious for the vast majority. They knew it had low mortality rates and they knew who was at most risk. Whitty said the severity of the virus did not justify experimental authorisation for a “vaccine.”

Yet for 18 months or so, they stood at the No.10 podium, either silent as Johnson/Hancock/ Gove/Sunak lied to the nation. Or they opened their mouths, deployed their rigged stats, and lied themselves.

In what way are their reputations enhanced? They are culpable for wrecking the economy, killing and seriously injuring tens of thousands and ruining the lives of millions.

They should be charged with Malfeasance in Public Office.

Manslaughter would be more appropriate

The author seems to have overlooked John Tamny’s book “When Politicians Panicked” as well as Iain Davis’ “Pseudo-Pandemic” and Justin Hart’s book “Gone Viral”.

Seems to be a serious ivory tower problem here – there has been a boatload of (real) journalists critical of everything to do with the fake pandemic since the very beginning – the problem is not these journalists, the problem is the ‘mainstream media’, call it what you will, which only employs hacks/sellouts/etc (who do NOT deserve the appellation of ‘journalist’) who will write the corporate-party line. Bit surprised to see this nonsense in DS …

A notable example of a hastily written COVID book was NY Governor Andrew Cuomo’s self-serving account, published on October 13, 2020, barely 6 months into the crisis. (link at https://a.co/d/6RvKaJt) It was as if the Captain of the Titanic had written a self-congratulatory book while his passengers were still in the lifeboats.