Unlike the Swiss or Japanese, we British are not known for our health. After Malta, in fact, we’re the most obese nation in Europe. Fully 28% of us have a BMI greater than 30, which for a man of 5 foot 10, equates to a bodyweight of 96kg.

This should be a source of national embarrassment. And you’d assume the Government wouldn’t want to make it any worse. Which prompts the question, “What on earth did they expect lockdown would do?”

Back in March of 2020, we were told that we “must stay at home”. Only “one form of exercise a day” would be allowed under the new regime. Gyms and sports clubs were closed, and children’s play areas were cordoned off like crime scenes. (This was all in spite of emerging evidence that the chance of being infected outdoors was negligible.)

The full effects of lockdown on our waistlines are only now becoming apparent. And they they’re not pretty.

In a recent study, Feifei Bu and colleagues analysed data from the COVID-19 Social Study, a longitudinal survey of British adults that began on 21st March 2020. Note: the sample was not representative, so the researchers applied weights throughout their analysis.

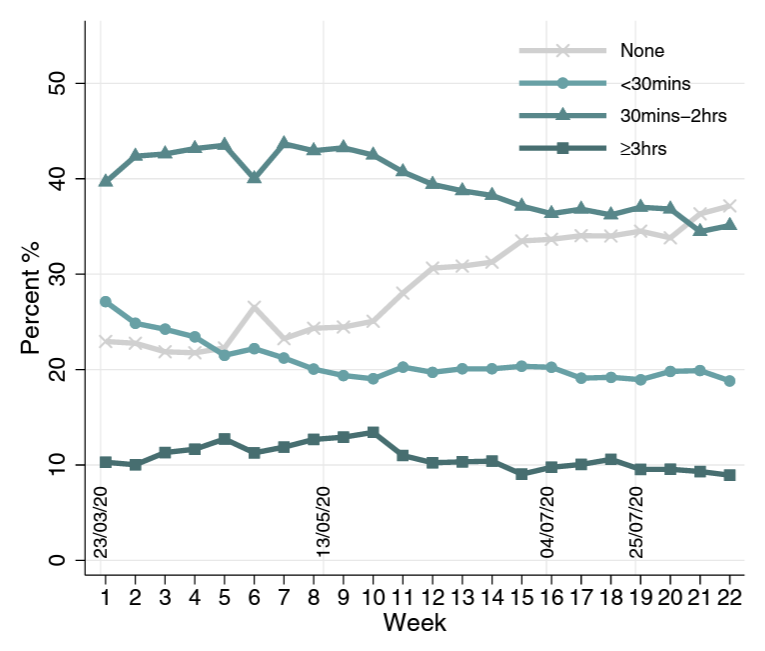

During the initial phase of the study (up to the end of August), respondents were asked about their level of physical activity on a weekly basis. In particular, they were asked how much exercise they had done on “the last working day”. Results are shown in the chart below.

Although the series begin after the start of lockdown, the percentage of people reporting no physical activity increased substantially over the duration of the study – from around 23% to almost 40%. Oddly, the peak of inactivity was not reached until the late summer.

If the government’s messaging had not needlessly emphasised staying at home, it’s plausible this change could have been avoided. In a recent meta-analysis, the majority of studies reported “decreases in physical activity and increases in sedentary behaviours” during lockdown. (Hardly surprising, you might say. But it’s good to have hard data.)

So that’s calories out. What about calories in? Perhaps people compensated for lower levels of activity by eating less. It seems they didn’t.

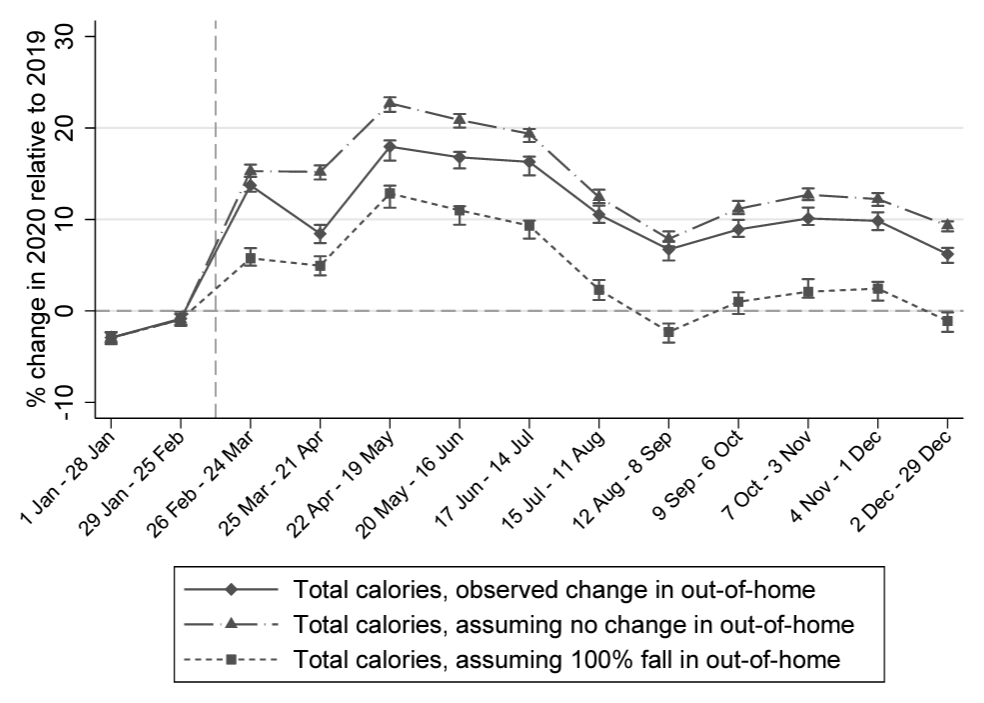

In a study published back in July, researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies looked at the impact of lockdown on people’s eating habits. They combined several sources of data to estimate the change in total calories consumed inside the home versus outside the home.

Unsurprisingly, there was a drop fall in calories consumed outside the home: although takeaways went up; visits to cafes and restaurants plummeted. However, this was more than compensated for by a rise in calories consumed inside the home. Results are shown in the chart below.

Each line on the graph corresponds to a different assumption about the change in calories consumed outside the home. The lower dashed line indicates that, even if you assume a 100% drop in calories consumed outside the home, there was still a sizeable net increase in calories – on the order of 10% or more.

Evidence suggests that, during lockdown, we did less and ate more. It’s therefore hardly surprising that 40% of British adults gained weight, with the average gain being half a stone. So you can add ‘20 million people getting fatter’ to the costs side of the lockdown ledger.

What’s more, 2020 saw the largest annual rise in childhood obesity – of 4.5 percentage points – since records began.

All this brings to mind the first of Martin Kulldorff’s twelve forgotten principles of public health. Repeat after me: “Public health is about all health outcomes, not just a single disease.”

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“In conclusion, Clauser argues that the negative feedback mechanisms in the Earth’s climate system stabilise temperatures against warming due to increases in radiative forcing.”

Yet one more amazing example among so many of intelligent design – that makes us literally unique in the universe we experience in our lives, in time and space. Our fine tuning is so fine that an infintesemal change in gravity or weak force that holds matter together and we don’t exist.

It’s called the Anthropic Principle – things are the way they are because it they weren’t, we wouldn’t be here to notice them. Strictly speaking, this is the Weak Anthropic Principle. Read ‘Just Six Numbers’ by Sir Martin Rees (Astronomer Royal) for an interesting discussion on just how ‘finely balanced’ six fundamental constants have to be for us to be here.

For some people, this provides evidence of a Divinity that arranged the Universe for us. For other (perhaps more humble) people it is not evidence that we are so special as to deserve the attention of the Divinity.

Consider the puddle which observes “Isn’t it amazing! This dip in the ground is EXACTLY the right shape to accommodate me”

So do you think all the incredible fine tuning that enables us to exist just happened by accident for no purpose?

I’m fascinated by the way Earth-colliding asteroids always manage to land in a crater. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220403-an-icy-mystery-deep-in-arctic-canada 😉

Yes, it did. Because if it hadn’t, we wouldn’t exist. There is no old man with a beard hiding out of sight, or even behind the curtain.

Rolling the dice a lot of times got us to where we are, with advantageous conditions leading to things persisting and disadvantageous ones destroying them.

Well I’m inclined to agree because if there were a ‘God’, not only would he not allow kids to suffer and die from terminal cancer but he wouldn’t have invented wasps. They’re not even very effective pollinators, compared with all the lovely, benign bees and flutterbies. No, wasps are the jihadis of the insect world, they lurk in litter bins and wait for an unsuspecting victim to pass by then chase them down the street, completely ignoring all other people, and I think they get a smug satisfaction out of making people behave like Mr Bean doing a demented windmill impersonation, basically humiliating themselves in public. They’re really hard to kill and i once squirted one with WD40 and it didn’t even die. It was like a bloody terminator! One stung me below my eye last year ( a wheelie bin ambush ) and it hurt like a f***er, so when one landed next to me I squashed it with my sandal and thought that was payback at least.

Creatures are only meant to attack you if they feel threatened or you’re on their menu, therefore there can’t be a god because such a benevolent being would never create such evil little b’stards. 🐝

Speaking of being on critters’ menus, I’m an ‘all you can eat’ buffet for 🦟, but I find staying consistently keto and those plug-ins you use overnight very helpful. No amount of garlic consumption works, alas.

Yes, it is difficult to understand why God allows suffering. You need to know that you would not exist to comment on the Internet if not for cancer, heart attacks etc. If nobody dies from disease then you have no chance at life at all because the planet could not support life at those levels. Suffering, ie Pain, is necessary to stay alive in our world so we know when things are harmful, when we become sick and that we shouldn’t put our hands in fire. If you have an alternative that is more sustainavle for the big picture,

love to hear it.

Bees mind their own business and are pretty polite. But wasps are nasty pieces of work sticking their nose into everything. “The jihadi’s of the insect world” is a pretty good analogy. A bee would never pass Net Zero, but wasps are a combination of Jim Dale, Ed Miliband and Antonio Guterres.

🤣

But wasn’t Jim Dale on Neighbours? Then he seemed to pop up all over the place after that, a bit like Guy Pierce..🤔

Something that I’ve often wondered about bees though is why is it only the fluffy bumble bees i regularly rescue from getting squished on the ground during summer? I’ve never ever needed to come to the rescue of a honey bee.

Answers on a postcard please….✏📮🍯

Are we getting mixed up with our Jim Dales?—-The one I am talking about is the cretin always on GB news spouting junk science and running rings around Eammon Holmes and Anne Diamond etc because they don’t know anything about the issue.

Why do you assume that the only two possibilities are a man with a beard controlling everything or a universe which came into being somehow by complete accident with no purpose, and therefore as the former is implausible, it must be the latter? Those are clearly not the only two possibilities.

Quite. Given what we don’t know, the chances of what we do know explaining our reality is close to zero. Most people seem unable to grasp any other idea of an overarching force other than the one of God as depicted by religion. And, for most people, that depiction of God explaining our reality is either true or false – there are no grey areas. But it seems to me to only be a small step to consider other possibilities for our perception of reality. One possibility, for example, is that it is an old man with a beard. This old man, however, sits in a lab, in a future time, running an infinite number of simulations with subtly different inputs. That’s a possibility the ‘there is only science’ people should be able to consider.

Not sure what I believe, but I’ve had a small handful of experiences that cannot be adequately explained by our common understanding of reality. I don’t know what reality is, but I’m pretty sure it isn’t this.

Total nonsense and defies logic.

This is what I send to people that aren’t sure or, amazingly, are sure there is no God. Yet alone intelligent design.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=ajqH4y8G0MI

I don’t know about purpose. I don’t see how anyone can know about purpose. But we’re all different and I can only see this from my perspective.

Existence and consciousness seem utterly miraculous, mysterious and intrinsically inexplicable to me. I sometimes wonder if that’s what others call God. The whole business of existence seems utterly surreal to me. And we should keep using hydrocarbons and build more nuclear power stations.

Carbon mechanics are a useful long term storage method, but it’s also reasonable to make real time use of light from the Sun, in a similar fashion as the plants do. Alright, the plants do the medium to long term storage that we exploit, but the somewhat simplistic route of grabbing some energy to generate electrical power is still a decent idea.

Well maybe but you need a backup when the sun isn’t shining, which costs money, or affordable storage.

There is no ‘fine tuning’ – just billions of years of evolutionary trial and error, spontaneous order.

in a word: Yes.

It isn’t known, and probably can’t be known if other combinations of values for the six numbers would also result in a universe in which life could exist. If physicists ever manage to produce a grand theory of everything it could turn out that the values of the six numbers can’t be any different to what they are.

All that means is that in the entire Universe we are exceedingly, infinitely, rare; a probability with lots of zeros to the right of the decimal point, and no integers to its left. One doesn’t have to invoke ‘intelligent design’ – a concept with even even lower probability.

The point is that if some thing, some state, some combination of states, is possible (i.e. that is not prevented by physics) then in a big enough arena, of time and space, the probability of it happening is 100%. We just happen to be it; our universe has adequate temporal and spatial dimensions.

In terms of corporate capture I think the university provides a good illustration of the malaise at large generally in society. You become so dependent on sources of funding and rather used to lavish amounts of money for fancy new buildings – always soulless though regardless of how much they cost, that to go back to a purer time is both unthinkable and unworkable.. And at the point of deep capture it is impossible to relinquish them because everything has been scaled up. Just like how we are complentely dependent on existing systems of trade and global finance because huge populations means there is no credible way to scale back without catastrophe. This Ponzi scheme problem has already started to manifest in terms of falling numbers of overseas cashcow students and loans that were taken out on the assumption of ever growing numbers.

There is a real emergency which could’ve been prepared for if it hadn’t been clouded by the fake one and therein lies one of its evils. Virtually no potato crop in Britain this year because of the wetness. Any attempt to grow stuff in your garden would’ve been met by an unvanquishable number of slugs and snails. There are natural cycles and any responsible leadership would be thinking about how to maintain such high populations under current conditions given long term trends There would be no easy fix but with international collaboration it could be done but it is too late now. We, the golden billion as the Russians call us, think we can just always rely on imports because of the permanence of the petrodollar. The luxury of imports is closing down on many levels. And many other countries are experiencing weather-related difficulties. I used to buy a litre of olive oil for £3 in the supermarket. Now it is £7.50. Things are at crisis point when you can’t even grow your own tatties. Do you really have to meet up with a spiv under furtive conditions in order to buy a vegetable. We think root vegetables are as hard as nails and will be with us forever.

We thought the events of 22/11/63 meant very little at that the time to us.All over Europe there was a geneartion who called themselves Kennedy’s children It was the start of a slow moving plague. Killed in broad daylight. They could’ve killed him by poison but they wanted it to be in the bright sunshine for maximum trauma. Any movement towards redemptive change acknowledges this. Dylan wrote a song about it a couple of years ago called Murder Most Foul.

It is sad for me because I love the Brits but all I see is a suicide pact or acquiesence to doom. No direction home. We are beyond the eleventh hour.

Off-T

https://thenewconservative.co.uk/sunaks-mask-slips/

Frank Haviland gives Fishy a good going over for his desertion at the D-Day ceremony. He’s a horrible weaselly little traitor.

“Unfortunately for Rishi, there is a reason beyond the general election why this D-Day storm is unlikely to blow over: it perfectly adumbrates the fault line along which all political issues are now at play in our nation– the stark divide between patriots and traitors.”

As I have posted more than once, Fishy is definitely on the side of the traitors.

True but I have been slagging them off when they are there including Charles that GBN are sycophants over. Neil Oliver alluded to similar lines in his monologue, maybe he reads the comments LOL.

I like the very simple quote from Judith Curry (Climatologist formerly of Georgia Tech) ———-“Sure, all things being equal CO2 may cause a little warming, but all things in Earth’s climate are not equal”.

How many ordinary people have head of John Clauser or other people like him, and how many will ever read an article like this or these type of studies? I suggest a tiny percentage only will do that. This means they will only be hearing the alarmist version of reality as presented on mainstream media (BBC, SKY News etc)

Here is a little story I read in a book by Stephen Einhorn called “Climate Change, What they rarely tech you in College”———-According to Jewish folklore, The Lord sent two Angels down with a sack full of foolish souls to be evenly distributed over Earth, but they tripped and fell spiling them in a little Polish town called Chelm. Soon a heated argument started in the town about what was more important, the Sun or the Moon. After careful consideration the Chief Rabbi decided the Moon was more important because it shone light at night when people needed it and not during the day when there as already plenty of light. It therefore quickly became settled that the Moon was more important. In fact there was a “consensus” and those who disagreed were classed as “Moon Deniers”.

There is something very similar happening today and many people getting their information from mainstream TV News are like the people of Chelm. They don’t look at facts and empirical science. They listen to Authority.

I don’t pretend to understand all this.

But I do know when I’m being fed bullshit and am being scammed – and the Climate Change propaganda is clearly bullshit and Net Zero is just a scam.

Put another way: what caused 12 000 years of global warming prior to Mankind burning fossil fuels, and when C02 levels were much lower, and what evidence is there that this process stopped at the end of the 20th Century or was so weak to be replaced by Man-made – and only Man-made – CO2 emissions?

Since nobody can answer that, the whole Man-made climate change crisis is a pack of lies. (Like CoVid and ‘vaccines’.)

Am I mistaken in what I seem to read here? A recently accoladed Nobel laureate, qualified in a highly relevant field, denouncing the entire climate scare as a scientifically-illiterate scam?

Why isn’t this covered by the BBC?

Since 2005, BBC policy has been to give no coverage to the climate sceptic viewpoint. And apparently never to revise or even reconsider that policy.

Prof Clauser is by no means alone. His thesis above is a condensed version of Prof Roy Spencer’s small highly readable book Global Warming Scepticism for Busy People. Prof Ian Plimer, distinguished emeritus professor of geology, would stand beside them both in a debate, if the BBC would allow one.

Add Professor William Happer, Professor Richard Lindzen, and many others.

The story of unanimous science support for AGW is simply a lie. It incenses me to think of it.

I will not pay the BBC’s wretched license fee. Let them come and put me in jail.