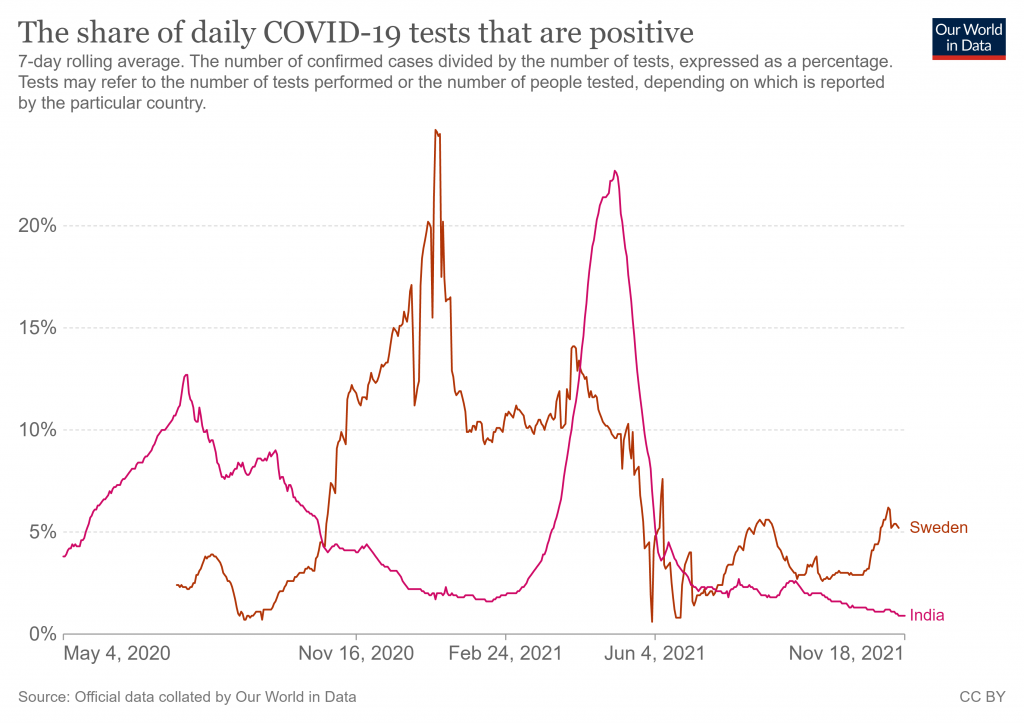

Why are some countries surging this autumn but others aren’t, at least not yet? Much of Europe is now seeing sharp rises in reported infections. In some it appears to be a delayed Delta surge, but in others like France, Netherlands, Norway and Finland it comes after an earlier summer Delta ripple that looked like it had gone away. Yet India, which had (quite literally) the mother of Delta surges, has not seen any new rise despite only 29% of its population being double-vaccinated, and despite the festivals of Diwali and Durga Puja, widely warned about as a transmission risk, taking place in the autumn.

Sweden, meanwhile, has somehow so far managed to avoid Delta surges altogether, after being hit relatively hard in spring 2020 and winter 2020-21. The country famously imposed only light restrictions (no stay-at-home orders, school or business closures or mask mandates at any point). Similarly, few restrictions were imposed in India in 2021, and there is also doubt about how far Indian citizens have followed any restrictions that were brought in; in any case, high population antibody rates were subsequently reported. Are India and Sweden benefitting from a more robust immunity owing to greater exposure prior to this autumn? What happens this winter will help to clarify this question.

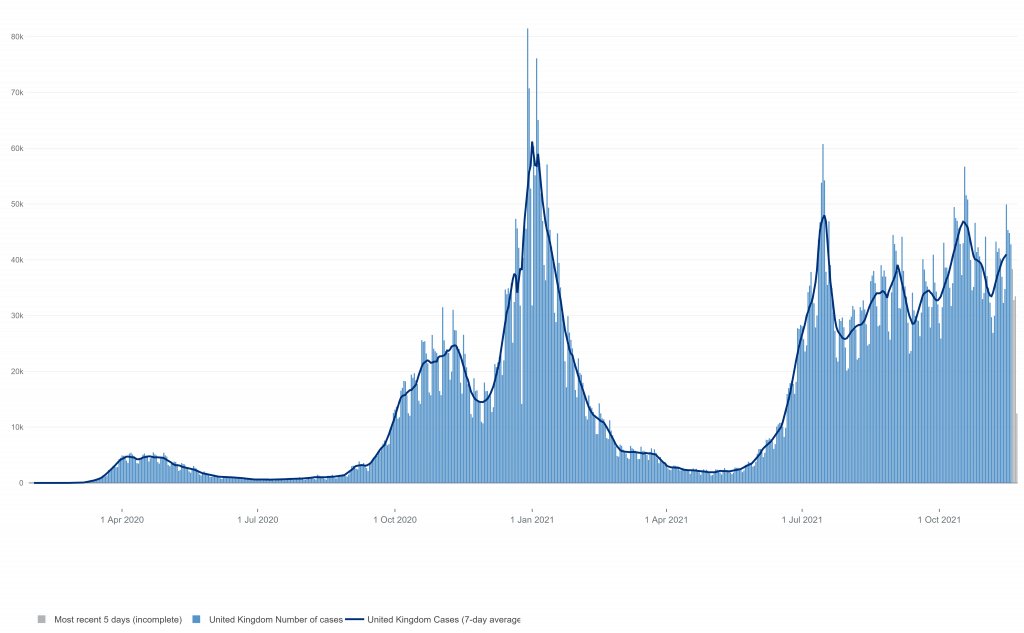

The U.K. meanwhile is experiencing a strangely drawn-out Delta epidemic. Beginning in June, it has now been simmering away at around about the same level for five months, neither exploding as the models predicted, nor dropping off again back to low levels, as earlier waves have done.

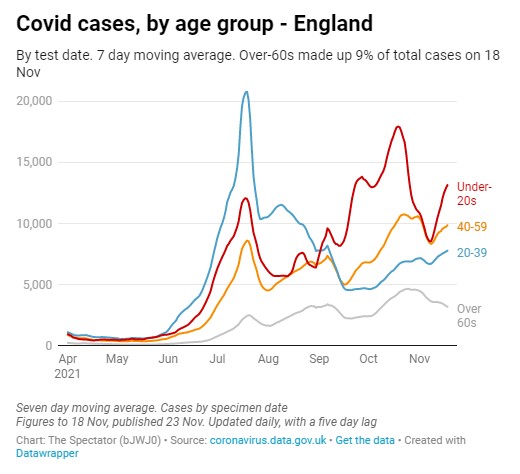

Why is the U.K.’s Delta epidemic so long, drawn-out and relatively flat, unlike the outbreaks in say India, Florida and Texas? The answer appears to be that it has consisted of a series of waves occurring one after another in different age groups.

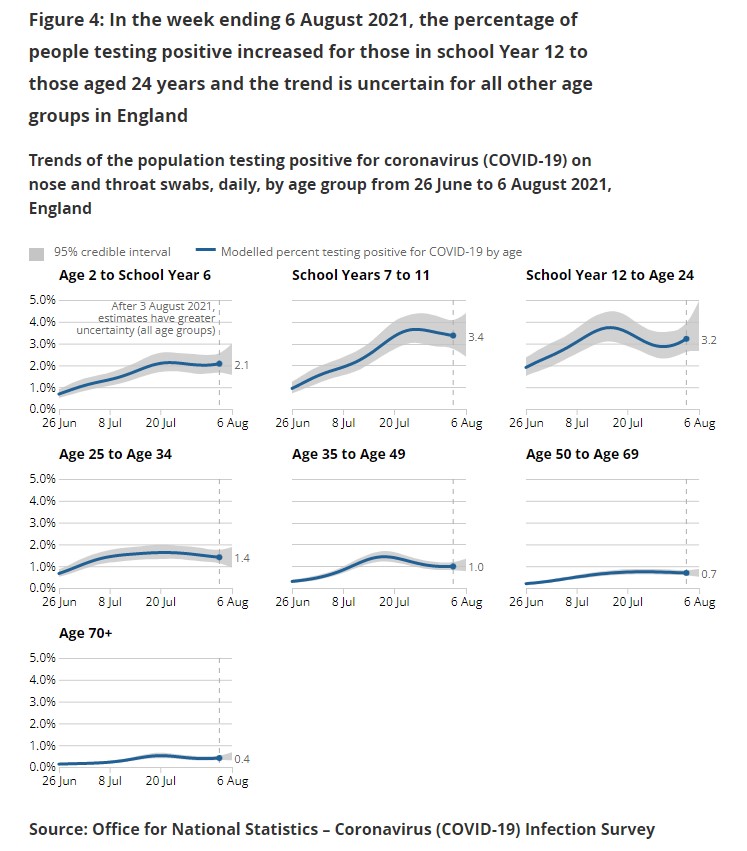

Initially, the surge in June and July occurred in all age groups. Note that the sharp drop in raw cases in mid-July was largely an artefact of reduced testing as schools broke up for the summer, though infections certainly did not continue to increase at that point.

Then came an extra bump among students and young adults. Was this driven by summer festivals? The subsequent bump in 40-59 year-olds may have been their parents.

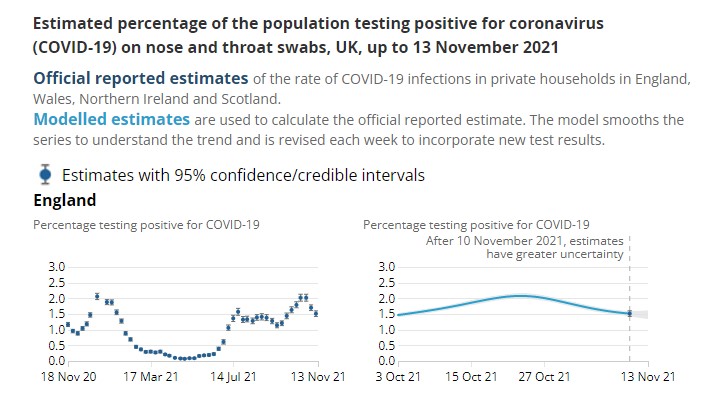

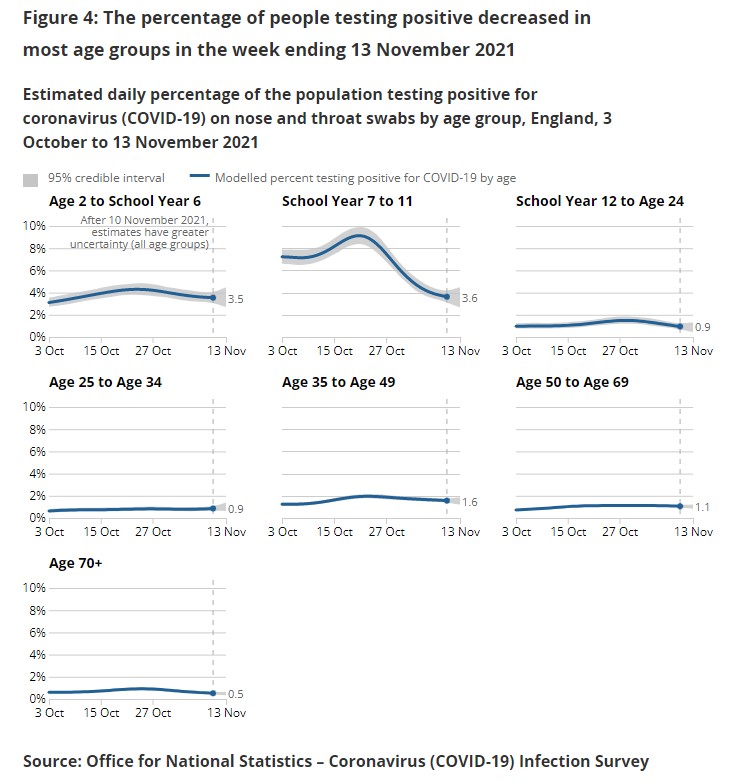

Then it was the turn of under-20s, and especially secondary school children (aged 11-16), getting up to a massive 9% prevalence in mid-October before coming down again fast. Their parents (age 35-49) may also have been affected. More recently there seems to have been a rise in all under-60s, possibly owing to the onset of winter.

Being frank, I didn’t expect this five-month long, demographically-staggered wave, and I’m not sure why it’s happened here and not so much elsewhere. Did we reopen more than other countries in the summer, triggering an earlier Delta surge, but not resume normal interaction enough for it to be a traditional big wave, like in India and the southern United States? How much do restrictions and behaviour changes affect transmission anyway when most studies suggest they make at most only modest impact? I’ve also been surprised by how many secondary school children caught it in this wave, given it had already gone through the country twice. How did they avoid exposure in both spring 2020 and autumn and winter 2020-21? Perhaps they were more susceptible this time round. But it’s still pretty baffling.

As I noted in a previous post, SAGE is now predicting the epidemic will decline during the winter, which would be most unusual. I would expect instead a modest surge, as usually happens in December. Either way, though, this is clearly a virus in an endemic state, and the Government should stop treating it as a special threat and de-escalate their response as soon as possible.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the same rules regarding the compulsory wearing of muzzles come into force here. They’re a very obvious sign of obedience to the ‘roolz’ and those of us who are sceptics would be easily identified.

Re: ‘Plenty of sunshine leading to reduced vitamin D deficiencies

Generally low levels of hygiene which suggests higher levels of resistance to infection’

My granny used to say ‘You have to eat a peck of dirt before you die’. Children are not being done a favour in being taught fanatical handwashing, or in being slathered in sunscreen every time they step outside.