A study appeared in the Lancet this week confirming that vaccine effectiveness against infection is fading fast.

The study involved 3,436,957 people over the age of 12 who are members of the healthcare organisation Kaiser Permanente Southern California. It sought to assess the effectiveness of the Pfizer vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19-related hospital admissions for up to six months, with a study period covering December 14th, 2020, to August 8th, 2021.

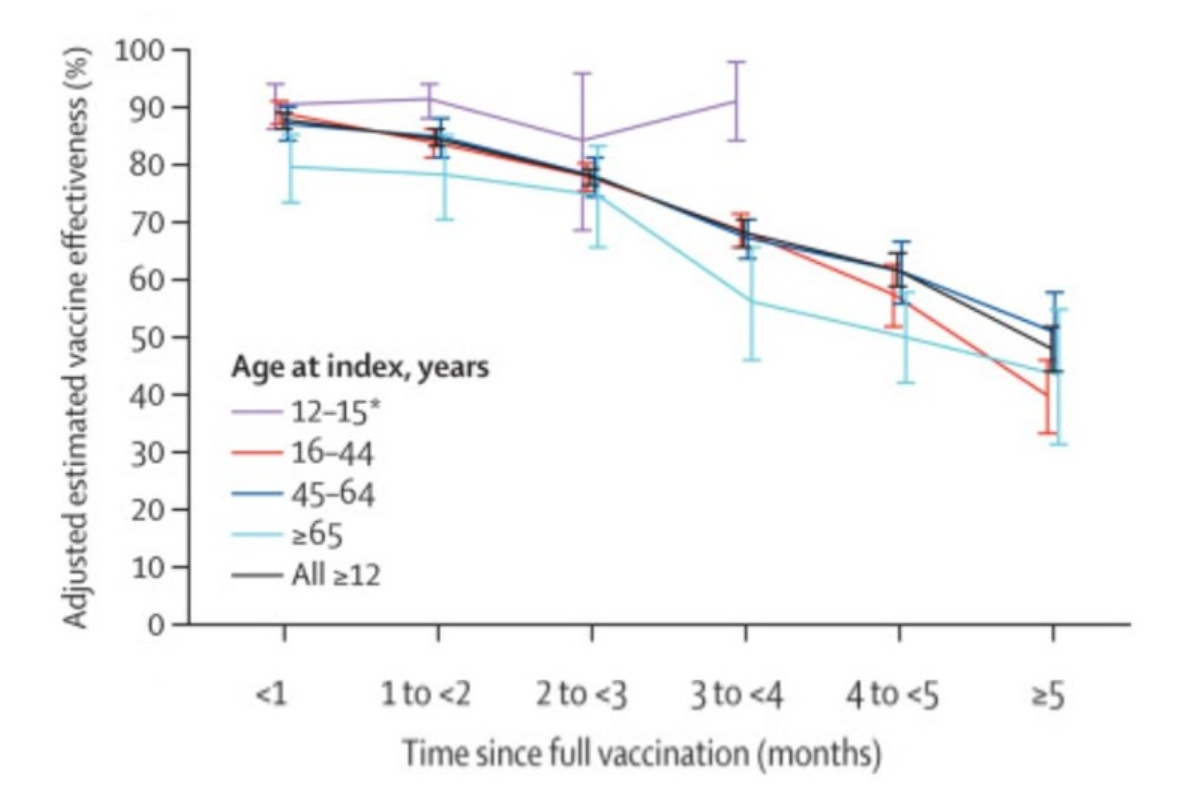

Comparing fully vaccinated to unvaccinated, and controlling for confounders such as prior infection, the researchers found that effectiveness against infection plummeted from 88% (95% confidence interval 86-89%) during the first month after double-vaccination to 47% (43-51%) after five months. The variation by age (depicted above) was largely within the margins of error.

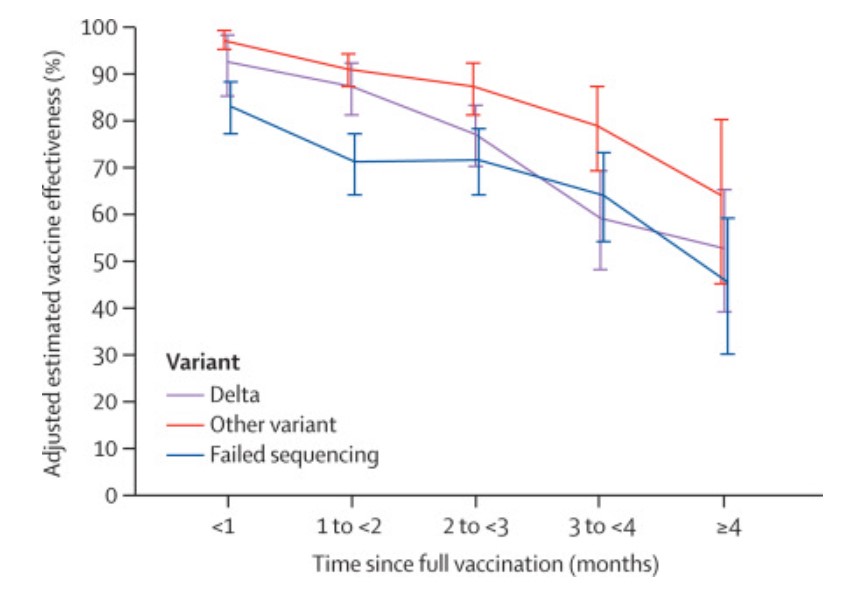

Among sequenced infections, the researchers found vaccine effectiveness against Delta infection was 93% (85-97%) during the first month after double-vaccination but dropped to 53% (39-65%) after four months. Effectiveness against infection from other variants the first month after double-vaccination was 97% (95-99%), but declined to 67% (45-80%) at 4-5 months.

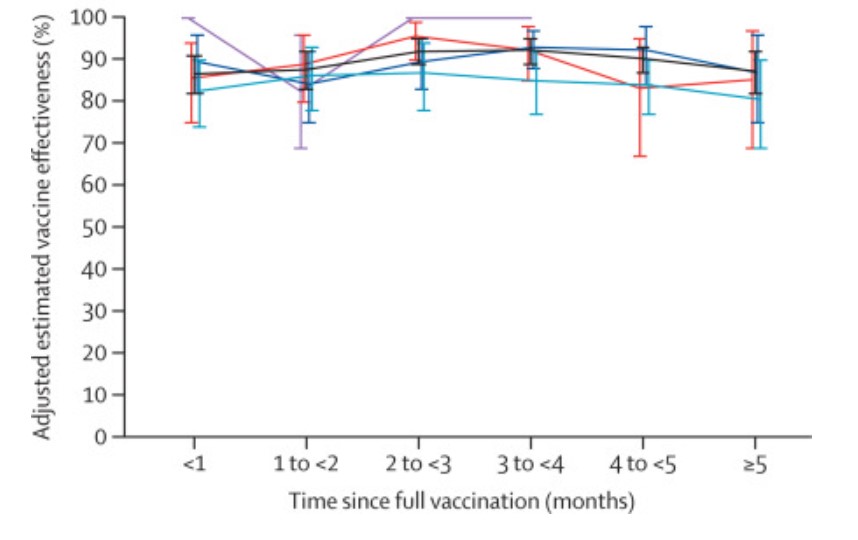

Vaccine effectiveness against hospital admissions for Delta infection held up at around 93% (84-96%) for the six months across all ages.

However, the researchers note that the latest data from Israel “suggests that some reduction in effectiveness against hospital admissions has been observed among older people (65 years and over) roughly six months after receiving the second dose of [Pfizer]”.

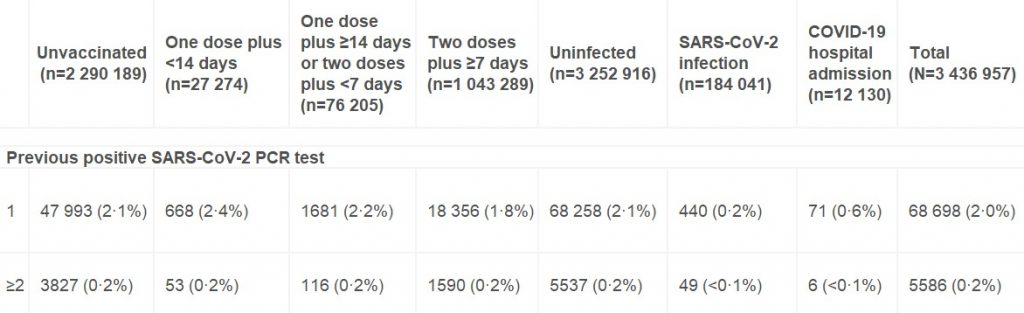

One question that’s arisen recently is to what extent vaccine effectiveness estimates are affected by whether more people who have been previously infected decide not to be vaccinated. According to this study the answer is: not very much at all. Among the unvaccinated, 2.3% had one or more previous positive PCR tests, only slightly more than the 2% of the double-vaccinated who did.

It’s also worth noting that although this study adjusts its raw estimates for no fewer than 22 potential confounding variables, the adjusted figures differ very little from the unadjusted figures in almost all cases. This suggests that unadjusted estimates from large population samples are often a fair approximation in the absence of sophisticated statistical analysis.

Given that the adjusted figures were little different to the unadjusted figures, however, it’s not immediately clear why the vaccine effectiveness estimates in this study, while low and declining, are so much higher than the latest unadjusted estimates derived from Public Health England data (namely, negative vaccine effectiveness in the over-40s, including minus-66% in those in their 40s). It doesn’t appear to be merely a matter of additional time elapsing, as most people in the U.K. weren’t double vaccinated until April, May or June, meaning only four or five months have elapsed until September, the same time period as in the study.

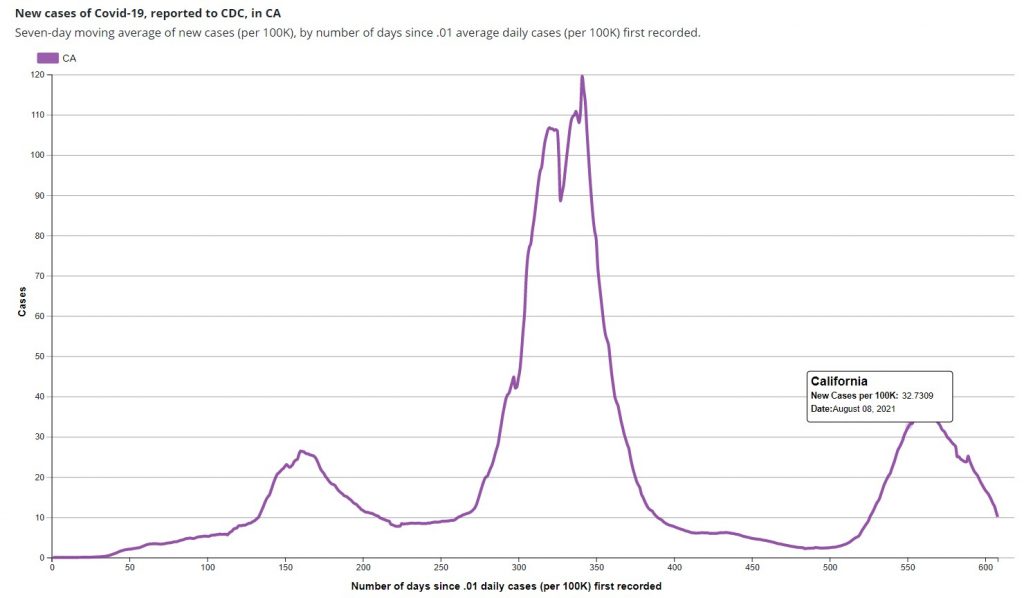

Could it be because the study period ended on August 8th, when the Delta surge in California was just getting going (see below)?

In the U.K. the vaccine effectiveness didn’t plunge until the second half of the Delta surge, the first part being dominated by infections in the unvaccinated (for reasons still not entirely clear). Did the new study finish too early to see the dramatic effect we’ve seen in England?

The authors say their study indicates that the decline in vaccine effectiveness is primarily a function of time rather than variant-related. However, the evidence from England would suggest otherwise, as in the same period of time, but later in the Delta surge, the decline has been far greater.

The decline in vaccine effectiveness in England was confirmed last week in a new Government-funded study (not yet peer-reviewed), which found that the reduction in transmission “declined over time since second vaccination, for Delta reaching similar levels to unvaccinated individuals by 12 weeks for [the AstraZeneca vaccine] and attenuating substantially for [Pfizer]”. In other words, within just three months AstraZeneca did nothing to prevent transmission, and Pfizer was scarcely better.

One of the main recommendations of the authors of both studies in light of their findings is for regular booster jabs – in the case of the first, where many of the authors are employees of and investors in Pfizer, this may be deemed hardly surprising. However, if effectiveness against serious disease is holding up, why give people boosters just to stop them getting and spreading what is effectively a cold, and which bestows more robust immunity as it goes? Furthermore, if the effectiveness declines after as little as three months, is it even possible to deliver enough boosters to have any impact on infection and transmission? Would it not be much better to say that the vaccines, by offering personal protection from serious disease to those who want it, have done their job? Better to move on and abandon any ideas of vaccine passports and mandates and boosters, and in general the now almost wholly pointless obsession with Covid vaccines.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

BREAKING: Study Finds SEVERE Allergic Reactions To COVID Vaccine Are 400% HIGHER Than Normal“A study published in the peer-reviewed journal Acta Médica Portuguesa has found the rate of anaphylactic shock in response to the COVID vaccines is 400% higher compared to the normal rate for vaccines. And in the case of the UK’s Oxford/Astra-Zeneca COVID vaccine, the rate is at least 1,000% higher than the normal level.

According to the study, the FDA’s data released since January 18, 2021 shows an allergic reaction rate of 4.7 anaphylactic shock reactions per million vaccinations for the Pfizer vaccine and 2.5 anaphylactic shock reactions per million for the Moderna vaccine. This is significantly higher than the average safety threshold of less than one reaction per million vaccinations. ”

This is published as “breaking news” but it appears the study has been around a while. That said, I don’t recall seeing it reported previously. Must have missed it. What with not watching the BBC, I suppose I missed their front page headline coverage..

I will admit that, for various reasons, I have been keeping an eye on the BBC’s coverage of this shambles, and I don’t recall any such story. I suppose that their view is that as this is a global emergency (or whatever) this is largely irrelevant. So two possibilities then. Either the all cause mortality data from Belarus up to March is wildly inaccurate – and likewise the “Covid” IFR data from places like Sweden and South Dakota (and Utah) -compared to other countries; or else, they are broadly accurate (or at least not significantly worse than other countries) and therefore the BBC is wrong to ignore this story and, notoriously, give coverage to someone who claims these “vaccines” are 100% safe. Is there anything to change my belief that there is no evidence of an emergency that would justify ignoring evidence of severe allergic reactions to an experimental “vaccine”?

“I suppose that their view is that as this is a global emergency (or whatever) this is largely irrelevant.” It’s been made clear to me by Michael Wendling that his view is that the public are not qualified to decide on the relative importance or validity of views. I imagine his view is fairly common. Wise Men and Women at the BBC need to filter the world to make sure nothing dangerous reaches us plebs.

This is hardly news at all. It was known from early days that these vaccines were more likely than most to lead to allergic reaction and anaphylaxis which is why you are asked about history of allergies before being vaccinated. In fact these estimates – 2.7 to 4.7 per million doses – are lower than many other estimates – this one had it as high as 250 per million. The risk remains very small and perhaps the key sentence is:

For all vaccines, no anaphylaxis-related deaths were reported.

The dead can’t report their own deaths and the jabbers, being those doing the killing, are unlikely to do so

The dead can’t report their own deaths and the jabbers, being those doing the killing, are unlikely to do so

It was a formal study – all the participants would have been monitored by the researchers to see what happened to them.

Outside the context of formal studies – very few people die without someone knowing – most people have friends, relatives or medical professionals attending them (other than the jabbers) who will report their deaths.

… but you are quite prepared to ignore the fact that any possible benefit from ‘vaccines’ is also ‘minute’ to ‘non-existant’.

I think you need to stop busting a gut to defend the indefensible (in terms of medical ethics) narrative. The angels are all on our side.

Obviously I don’t agree – it turns out to be surprisingly easy to refute much of what is written about vaccine here – no need to bust a gut. What is harder is to get people to read what I wrote – as opposed to what they think I wrote.

“it turns out to be surprisingly easy to refute much of what is written about vaccine here”

Why haven’t you managed it then?

My God, until now I have been polite in deference to your age ( am I only a bit younger ) – no longer; you have no fucking idea about which you spout.

The party line from the jab manufacturers is that unless you are allergic to something in the jab, it is “safe” – may be “true” from their POV – but otherwise is bollox.

An over primed immune system can suddenly react to anything, repeat anything for no apparent reason. Guess what this jab does; it over primes your immune system – in other words induces ADE, a fact of previous vaccines according to medics, virologists and vaccine developers. Studies are available so don’t bother to raise the “fact checker bollox as with Full Fact, you know the one ” we are independent” but “we take money from George Soros and the Esme Fairbairn Trust” and so on.

Not satisfied with the above over priming, these mRNA jabs are known to have killed people as a result of a cytokine storm; in layman’s language a massive immuno over reaction. The mRNA jab induces the production of a spike protein which is an antigen. Anaphylaxis is an acute Life threatening reaction to an antigen. Get the connection?

So if you are immuno compromised due to an existing anaphylaxis condition – like me – you might rightly fear some kind of aggressive immuno response both from the jab AND from a subsequent infection OF ANY TYPE that an overprimed immune system reacts to – lethally.

I asked a certain question of the Anaphylaxis Campaign; My request to the Anapyhlaxis Campaign got this response:

“Anapylaxis is not contraindicated according to page 30 of the “Green Book”.

The vaccines do not contain the proteins in the (my redaction) that trigger an IgE mediated reaction, therefore there would be no basis whatsoever to suspect that a COVID-19 vaccine could trigger (again my redaction) anaphylaxis. ”

This is over simplified and nowhere close to the findings of studies into SARS COV 2 “vaccines” and anaphylaxis.

But they won’t say – to my direct question – if they have had information from Pfizer that their pre EUA trials that it was tested on people with a history of Anaphylaxis – in other words no such tests were done. So that’s great, don’t take the jab if you are allergic to any component the jab; how the fucking hell can that be possible when these manufacturers have not to date revealed the entire suite??

AND YOU FUCKING DARE TO SAY:

“The risk remains very small and perhaps the key sentence is:

For all vaccines, no anaphylaxis-related deaths were reported.”

NO, THE RISK IS A DAILY RUSSIAN ROULETTE FOR ANYONE WHO IS JABBED – AS I AM – AND HAS A HISTORY OF ANAPHYLAXIS; CYTOKINE STORM OR ANAPHYLAXIS IT IS ALL THE SAME.

TY/DS: please check this guys email for his IP address – I am sure you know how to do that “enhanced” – if there is any hint of a non private address, do the needful.

It is quite clear that, as Charles Richet noted in his Nobel lecture on Anaphylaxis in 1913,

“In 1903 Arthus, in Lausanne, showed that a first intravenous injection of serum on a rabbit causes anaphylaxis, i.e. three weeks after the first injection the rabbit is hypersensitive to the second injection. The phenomenon of anaphylaxis was becoming of general application. Instead of applying only to toxins and toxalbumins, it held good for all proteins, whether toxic at the first injection or not.“

“Two years later Rosenau and Anderson, two American physiologists, demonstrated in a noteworthy piece of work that the phenomenon of anaphylaxis occurs after every injection of serum, even when the injection is minute, for example of 0.00001 ml which is an infinitely small amount but nevertheless sufficient to anaphylactize an animal. They quoted examples of anaphylaxis from all organic liquids: milk, serum, egg, muscle extract.“

A succession of jabs will grant you an allergy whether you had one previously, or not.

What makes it worse is that the genetically induced spike proteins will form complexes with ACE2 receptors that will generate autoantibodies against ACE2 which is found all over the body.

These antibodies are swiftly becoming non-neutralizing antibodies as the RNA based viruses mutate, engendering ADE.

Thank you; I am “not a scientist” but you summation matches parts of a peer reviewed study from scientists in BC Canada I have read – very dense. It is personally frightening that these jab manufacturers have conned governments to waive liability for their worthless toxic concoctions, to say nothing of the “Russian roulette” I mentioned. Of course it will not affect everybody, granted, but the fact of the high number deaths from cytokine storms, as wells the other adverse effects, should be enough to pull these dangerous concoctions.

MTF and a few others just don’t wish to acknowledge what is “blindingly bleedin obvious”.

It’s way worse than that. A study at Mass General Brigham (published in JAMA on march 8th 2021) reported a rate of 2.47 per 10000.

The SWPRS piece is a good and important read, in particular in conjunction with a proper, aka non MSM&co analysis of the recent autopsies performed in Germany.

https://www.achgut.com/artikel/lymphozyten-amok_nach_impfung

“…the vital public health measure of vaccination…” writes josieappleton. An ironic choice of adjective, given the deaths the COVID shots are causing.

The Mises Wire one is a great article with plenty of valuable information.

In particular for Toby’s talk on Monday.

Much better and much more comprehensive than the headline and excerpt suggest- wrif.

As time ticks on it will not be long before it will be a year since some people had their Covid vaccinations. It makes me wonder how, having discovered the ‘weaponization of vaccination’ they are going to carry it forward? With the compulsory vaccination of care home workers in the UK, is there any time limit to this legislation? or is there some compulsory booster requirement?

They seem to have incorporated booster injections into the vax-pas system in Israel but in a country like the UK this will not be easy. The nightmare that is now the vaccination procedure for International travel will get worse and worse if they try an include boosters into the entry requirements.

As it seems to be acknowledged that these injections are time limited how long can this vax-pass business continue?

…as long as people continue to ‘offer’ their arms to be injected.

or as long as the meddlers keep their phoney baloney careers in government.

UnHerd is such a great site. We all knew Anders was right.

and yet he still pushes a lot of the same bullshit rather than sticking to the original plan (testing and contact tracing) and has clearly also been bought by the pharma industry with his line about the voodoo medicine saving the world.

… but wrong about the snake oil.

Mind you, many thought that it was excellent news when May was ousted. And yes, it was – but look what then happened!

I get frustrated reading these ‘Noway back to normal’ type articles (similar with Denmark the other day). In what way is this ‘normal’?:

From 4pm on 25 September, travellers from the UK without a valid QR coded NHS COVID Pass are required to stay in a suitable location e.g. hotel or home, for 10 days.

I would love to know the honest reasons for this. Sweden also had restrictions on people coming in despite having very few domestically. Is it a sop to the bedwetters in their own country? Or a sop to some sinister agenda? Or do they really believe it is necessary? I think Option 1 is most likely, but who can say?

Politics. Sweden , in the EU, allows EU/EEA visitors with antigen test within 72 hours. But not from UK because its outside EU/EEA at least until end of October.

Noway, outside EU, has more or less followed the UK model.

Its nothing to do with ‘health’, but all to do with politics, as are most of the restrictions.

For instance Panama started making US visitors quarantine for 10 days as soon as Biden WH made it clear that from November non-vaxed Panamanians would not be allowed in US. Tit for tat, its going on everywhere.

Now, now: you are not supposed to remember how the world used to be!

“Serious Group of Scientists Declare COVID-19 Vaccine Risks Too High to Ignore”

And as the mandatory update “BOOSTERS” become a key component of this NEW NORMAL… the adverse affects will multiply.

See where this leads to yet?

Sharing links that are behind bloody pay walls though! Ugh..what’s the point? And Trialsite News used to be a quality read. Can’t see the Denmark piece either.

Oops, I meant ‘Norway’.

Easy mistake to make.

Anyone else spot the ‘festival’ screened by the BBC last night, called Global Citizen Live? *shudders*

I’ve heard that phrase (minus Live) so many times recently, mainly in the same breath as a certain agenda…

There’s a website, partners include Google, Comcast, MSNBC etc.

https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/partners/?type=partnership

Quote:

so the same globalists who conspired over the past 18 months to throw millions more into extreme poverty now claim they want to end it?

Well I guess letting them all starve to death would mean they’re no longer counted as being poor.

Indeed. It’s clearly straight out of the Agenda 2030 playbook, the same goals – so-called “sustainable development”, “ending poverty”, it’s all Orwellian double-speak. They are pushing mass migration across vast distances, there’s nothing sustainable or environmentally friendly about that either.

They’re ending ‘extreme poverty’, but if everyone is poor to an equal degree, then they can drop the word extreme can’t they.

Well, Live Aid hasn’t done much to relieve Ethiopian poverty. It did however fund quite a lot of armaments for rebel groups.

Their aim was simply to feed the starving in one country, but these days any publicity has to have global intent which will present opportunities to a much wider range of despots.

We see during the weeks of winter, that there is a significantly greater number of total deaths in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. This trend continues and is more pronounced in the period up to July as overall deaths decline due to the roll out of spring and summer.

This gives the lie to the effectiveness of the vaccine as the talking heads disingenuously stated that most cases in the hospital for this period were unvaccinated. Most of the population had been unvaccinated at this time and of course this would be the case. The lie fails to hide the deaths due to vaccination however.

Note how keeping all eyes on delta, makes it appear that there is little difference between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. As we shall see, this is due to the distorted testing protocols for covid 19 heavily weighted against unvaccinated patients and the use of the fraudulent 40+ PCR cycle thresholds.

Week 18 corresponds with the date of April 15th where >50% of adults have received the first dose.

At this point we see total unvaccinated deaths at 4 per 100,000

And total vaccinated deaths at 27 per 100,000

Therefore, there is a 675% difference in vaccinated deaths versus unvaccinated deaths when just over 50% of population had received the first dose. It’s age standardized, so it gives a fair indication that vaccines are causing the excess deaths which occur around the beginning of June.

As autumn and winter encroach, we await with trepidation the ONS data for the 2nd half of the year.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/deaths-involving-covid-19-by-vaccination-status-england-deaths-occurring-between-1-january-and-2-july-2021

Dr Cahill’s main prediction was that it would be after several months, a year, or several years that the truly adverse events would occur. They would be due to the immune super priming, the setting up of auto-immune disease and cytokine storms as outlined above in this article. The mRNA in the body would express the viral protein, and the immune system would see antigens in the body’s own cells and organs and attack them. The binding antibodies induced would then enhance the entry of the wild virus and other common viruses into the cells and trigger further immunopathology. Those with co-morbidities would have exhausted cells and be unable to resist the onset of organ failure, sepsis, and death.

https://bakerstreetrising.home.blog/2021/09/17/and-if-you-go-chasing-rabbits-and-you-know-youre-going-to-fall-update-september-18th/

They are going to blame it on the flu, aren’t they, already suggesting it could be a bad flu year?

That and the variant.

Amazing coverage of the terrorism, tyranny and acts of war being carried out by the Australian government against its own citizens from Max Igan:

The Killing of Australia

https://www.bitchute.com/video/u8WwR1Ox42cU/

The Rule of Law is Gone in Australia it is Now Under The Rule of Thuggery

https://www.bitchute.com/video/zveuj9o1TuqS/

The video of the police swaggering up to a woman sitting in a park and snatching her phone and scrolling through it is disgusting, shows the utter lack of respect for the citizens of Oz, hope when the time comes, they regret it.

Dr. Eli David

@DrEliDavid

Israel last month: 20% of population unvaccinated

Israel today: 65% of population unvaccinated

After definition of vaccinated was changed to 3 shots.

9:07 PM · Sep 25, 2021·Twitter for Android

https://twitter.com/DrEliDavid/status/1441856850480308228

LOL!

(Not sure what the situation is here – probably depends whose definition and for what purpose. Comments suggest variously that the definition is actually “vaccinated in last 6 months, or that they decided not to change the definition.)

But the underlying point remains – “vaccinated” status for totalitarian control purposes will always be a mobile goalpost, at the regime’s discretion.

Australia – a free and liberal democracy.