One of the claims put forward by the authors of The Great Barrington Declaration is that lockdowns unfairly shifted the burden of COVID-19 onto the working class. As Martin Kulldorff and Sunetra Gupta argued in a piece for the Toronto Sun last November:

Low-risk college students and young professionals are protected; such as lawyers, government employees, journalists, and scientists who can work from home; while older high-risk working-class people must work, risking their lives generating the population immunity that will eventually help protect everyone.

The same idea was captured in a viral tweet by the art critic J.J. Charlesworth:

To evaluate this claim, let’s begin by looking at some of the data from Britain. Last July, the ONS attempted to quantify the extent to which different jobs can be done from home. Unsurprisingly, they found that higher-paying jobs in the professional and managerial classes are much easier to do from home, whereas lower-paying jobs in the skilled and unskilled working class are much harder to do from home. (‘Front-line doctor’ is an exception.)

While “key workers” are drawn from all income deciles, a relatively large percentage are drawn from the 2nd, 3rd and 4th deciles – particularly in the food and necessary goods sector. And according to the ONS, 15% of such workers were at an increased risk of COVID-19 because of a pre-existing health condition.

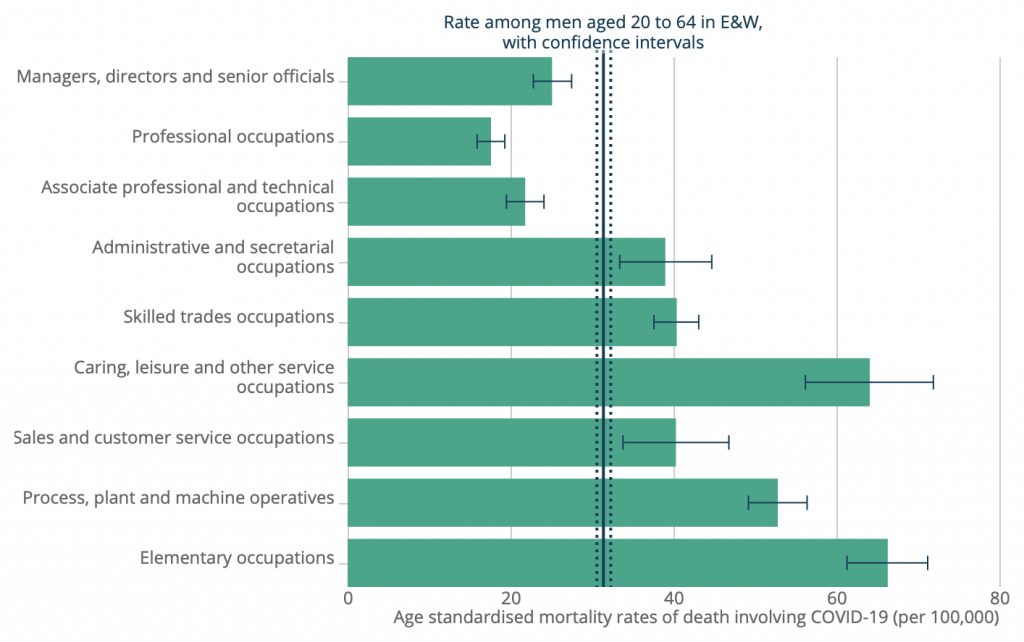

In January of 2021, the ONS computed age-standardised mortality rates for COVID-19 in different occupations. They found that men in professional and managerial occupations were substantially less likely to die of COVID-19 than those in service and elementary occupations:

The pattern among women was similar, although somewhat less pronounced. (The highest age-standardised mortality rate was for women working as plant or machine operators.)

In a study published in Nature, Elizabeth Williamson and colleagues analysed data on a large sample of British adults, and found that individuals from the bottom quintile for area deprivation were significantly more likely to die of COVID-19, even after controlling for age, sex, ethnicity and a number of pre-existing health conditions. This may be because such individuals had greater exposure to the virus, although there are other possible explanations.

It’s important to note that men in elementary occupations and skilled trades are more likely to die for any reason than men in professional and managerial occupations. In other words, there is a mortality gradient across occupations for all-cause mortality, as well as for COVID-19. This means that the two gradients may be partly caused by the same factors – such as more men in working class occupations having pre-existing health conditions.

Furthermore, the fact that people in working class occupations were more likely to die of COVID-19 does not, by itself, prove that lockdown shifted the burden of COVID-19 onto the working class. Such people might have been more likely to die of COVID-19 even in the absence of lockdown – say, because they were less able to engage in voluntary social-distancing.

In order to evaluate the claim that lockdown shifted the burden of COVID-19 onto the working class, we need to compare countries or states that did lock down with those that did not. Of course, the only major country in Western Europe that did not lockdown is Sweden.

In an unpublished paper, Sunnee Billingsley and colleagues analysed Swedish data, and found that workers in frontline occupations were not more likely to die of COVID-19 when adjusting for individual characteristics. Their findings indicate “no strong inequalities according to these occupational differences in Sweden and potentially other contexts that use a similar approach to managing COVID-19”. This supports the Great Barrington Declaration authors’ claim.

Another way of testing the claim that lockdown shifted the burden of COVID-19 onto the working class is by comparing infection rates across social classes before and after lockdown.

In a study published in BMC Public Health, Nathalie Bajos and colleagues analysed French data, and found that individuals in the highest social class saw a substantial decline in the risk of infection after the country went into lockdown, whereas individuals in the lowest social class saw a much smaller decline. Though it’s possible these differences emerged due to voluntary changes in behaviour that happened to coincide with the start of the lockdown.

Overall, there is tentative evidence that lockdown did shift the burden of COVID-19 onto the working class. However, comparative studies will be needed to investigate this claim more systematically.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

They are paid to get their results to map to a pre-determined outcome.

If you want to discuss weather talk to a farmer.

If you want a new roof, talk to a roofer.

If you want data fraud, bullshit, bafflegab, fake footnotes – talk to a quackademic, researcher, thought leader, expert, Phd Pretty Happy Dude smoking his pot, paid by special interests.

You live in a dream world Neo.

Indeed. Having experience or qualifications in a particular domain doesn’t make you an expert. Those things MAY be a pointer to you being an expert, but your ability to predict outcomes at consistently statistically significant better than random chance is what qualifies you, at least in the scientific domains.

If we’re to give “the experts” the benefit of the doubt and are presuming their solutions were genuinely sincere (and not following some pre-planned agenda to usher in a dystopia), the simple fact remains when you’ve a collection of single-minded academics who specialise, even the smartest and most educated amongst us aren’t always the best equipped at seeing the bigger picture. They can’t see the wood for the trees, to coin a phrase and that’s not even including the group-think, echo-chamber phenomenon we know is a reality.

They’re often living completely different lives, indifferent to the daily struggles of many and perhaps it’s a consequence of our education system that breeds arrogance, or we’ve simply a finite amount of space between our ears but I know from experience, my brother is highly educated in an academic sense but is oblivious and quite useless at mechanical quandary (for example – it’s not a matter of talent, his brain works differently). SAGE proved their single-mindedness in their presenting a comprehensive solution to impact society with positive intent but failing to include and incorporate the collateral damage caused by their own interventions negated all their hard work and is only something that can occur when they’re held in such high regard and beyond reproach. Never again, I say – or at the very least they’ve a lot of convincing to do to regain our trust.

Everything SAGE has propagated had damaging direct effects and was claimed to have collateral benefits which couldn’t really be quantified. No serious scientist would refer to himself as sage. That’s already a bullshit term supposed to appeal to superstitions conjectured to exist in the general population.

A great day for mankind! The perpetuum mobile has finally been invented! Its composed of social scientists researching themselves in circles, thereby stimulation more social science research!

Expert predictions predictably bad

Yellow Freedom Boards – next event

Monday 7th November 11am to 12pm

Yellow Boards

Junction B3430 Nine Mile Ride &

New Wokingham Road,

Wokingham RG40 3BA

Stand in the Park Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am – make friends & keep sane

Wokingham

Howard Palmer Gardens Sturges Rd RG40 2HD

Bracknell

South Hill Park, Rear Lawn, RG12 7PA

As has been mentioned previously Social Scientist” is a classic oxymoron