Matthew Sweet has written in UnHerd about the importance of following footnotes in studies to find out if the references actually say what the studies claim they say and genuinely back up the argument being made. He suggests this indicates whether or not the study should be considered reliable.

One of his examples is the mask study by Dr Baruch Vainshelboim, now retracted, that I wrote about yesterday. He says a number of the footnotes are misrepresented (this criticism was part of the retraction notice).

If Dr Vainshelboim did misrepresent the papers he cites he would not be the first. As noted yesterday, a recent peer-reviewed study in PNAS claimed surgical masks filter out 95-99% of aerosol droplets. Yet the two papers it cites to back up this claim say nothing of the sort. One concludes: “None of these surgical masks exhibited adequate filter performance and facial fit characteristics to be considered respiratory protection devices.” This is not to defend Dr Vainshelboim’s misrepresentation of course, but to highlight the double standards applied to those who challenge political orthodoxies.

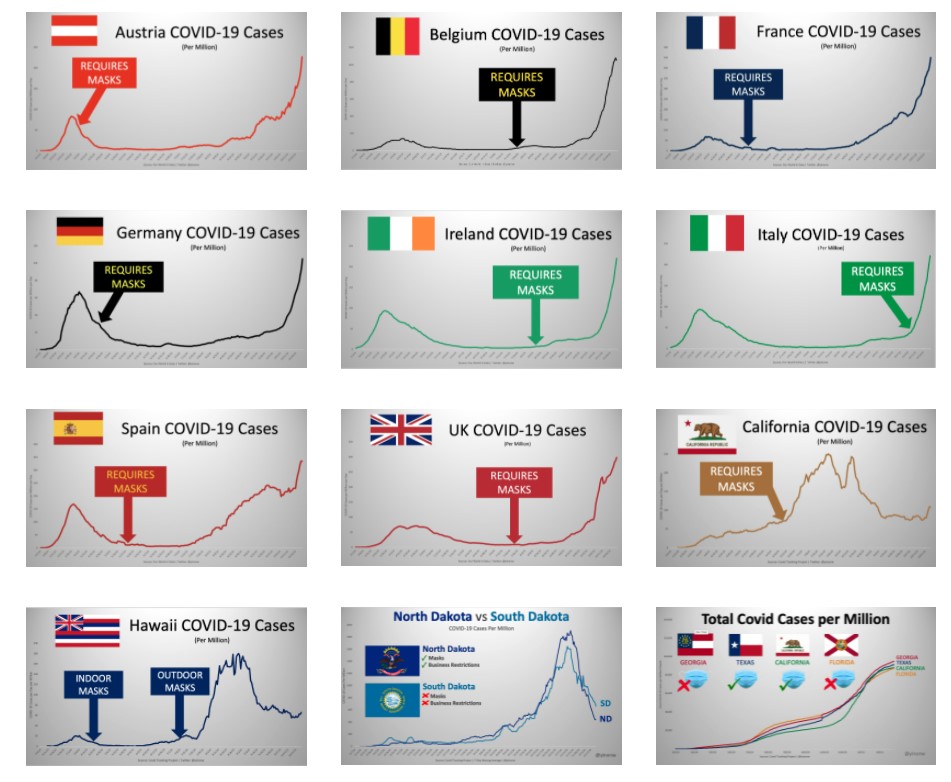

Today I thought I would follow Matthew Sweet’s advice for the Government’s own evidence. We learned yesterday that face masks may continue after June 21st, with no indication of when the mandate may be lifted or what conditions may trigger it. What scientific evidence is this seemingly permanent coercive public health measure based on? After all, the real world evidence for masks preventing outbreaks is feeble, to say the least, as Yinon Weiss has dramatically illustrated.

The Government has often been slow to publish evidence for its supposedly scientifically based interventions. But in January its scientific advisory group SAGE published a paper in which it set out its current evidence on masks. This included an important admission that masks give no real protection to the wearer, saying: “They may provide a small amount of protection to an uninfected wearer; however, this is not their primary intended purpose (medium confidence).” They say they are “predominantly a source control”.

Face coverings worn in public, community and workplace settings are predominantly a source control, designed to reduce the emission of virus carrying particles from the mouth and nose of an infected person. This may have measurable benefits in reducing population level transmission when worn widely, through reducing the potential for asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic people spreading the virus without their knowledge. Analysis of regional level data in several countries suggest this impact is typically around 6-15% (Cowling and Leung, 2020, Public Health England 2021) but could be as high as 45% (Mitze et al., 2020).

This is the key paragraph in terms of providing evidence for the effectiveness of face masks, and on closer inspection it is a mess. It says: “Analysis of regional level data in several countries suggest this impact is typically around 6-15%.” Yet the 6-15% figure comes from the Cowling and Leung paper, which is not an analysis of regional level data but an editorial article drawing on a December 2020 review paper by Brainard et al. The Brainard paper reviews 33 studies including 12 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), but none of these is an analysis of regional level data.

The Mitze paper actually is an analysis of regional level data, but only in Germany not in several countries. It was submitted in July 2020 and is based on data from the decline of the spring wave. As infections were falling then anyway it is very hard to distinguish the possible effect of masks from natural decline. In any case, the mask mandate in Germany did not prevent the winter surge, as the graph above depicts.

The Public Health England 2021 paper does not appear in the bibliography or anywhere else in the paper so remains a mystery as to what it might contain.

Brainard thus appears to be the key paper for evidence, and anyway is the source of the 6-15% claim. As noted, it reviews 33 studies on the effectiveness of face masks in preventing transmission of respiratory disease (not COVID-19), of which 12 are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The RCTs give the lower figure of 6%. The higher estimates all come from other, less robust types of study (cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies). Not included (because it wasn’t published at the time the review was written) is the one RCT specifically on masks for COVID-19 – Danmask-19 – which found no significant protection for the wearers of surgical masks.

Contrary to the claims of the SAGE paper, however, Brainard’s 6-15% estimate is expressly for protecting the wearer, not source control. Yet this is supposed to be SAGE’s evidence for masks as source control, having admitted they are no real benefit to the wearer. Brainard does look at the evidence for source control, but it grades the quality of the evidence as low or very low. Many of the studies it looks at show small reductions of around 5%, though some show greater reductions, while others show significant increases (e.g. one where masks are associated with a 200% increase in transmission). The best quality evidence (which isn’t saying much here) is five RCTs where all members of households (ill and well) wear masks, which indicate masks may reduce risk of infection by 19%. However, Brainard grades the quality of this evidence as low, remarking it was “downgraded twice overall for risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency”.

Brainard calls for “COVID-19-specific studies”. Danmask-19 is the only Covid-specific RCT so far. It wasn’t published in time for Brainard but it was in time for SAGE’s January paper, yet was not included. SAGE has yet to publish any advice which cites it.

So let us summarise. SAGE’s most recent advice on masks says they are of little benefit to the wearer and are “predominantly a source control”. In evidence of their effectiveness for this it cites three papers which it claims provide an “analysis of regional level data in several countries” that suggest masks reduce transmission by 6-15% (for two of the papers) and 45% (for the other). However, one of the papers cannot be traced, another (the source of the 45% figure) is a regional analysis of just one country (which despite a mask mandate suffered a large winter surge), and the other, the source of the 6-15% figure, takes the estimate from a review paper that includes no analysis of regional level data. Furthermore, 6-15% is its estimate for protecting the wearer not source control (with the lower figure coming from the most reliable studies) and it does not include any Covid-specific studies. Its evidence for source control it grades as low or very low.

Matthew Sweet was right. Following footnotes is eye-opening for exposing unreliable sources of evidence. Like SAGE.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

If they still want masks in the summer when all adults have been vaccinated *and* disease prevalence is near 0 (just as last year) then realistically there exists no scenario where they’ll EVER go away. You cant ever get conditions more suited to having no NPIs.

The SAGE report was ridiculous, lacking any useful RCTs measuring infections, ignores ALL the ILI infection RCTs hosted by the WHO prior to 2020 that show no difference.

Add to that a “face covering” is not a mask – its even less effective again by a huge margin.

Suspect they’ll now have SPI-B working on a propaganda campaign to normalise these idiotic things.

“A small price to pay for freedom” and other such nonsense.

One of the very WORST things of the entire lockdown was the dehumanising, unscientific masking up of the entire population and it seems they want to keep it forever.

Mask wearing will only stop happening if we can change the view of them.

What they actually signal is that you believe you are infectious and should be at home in bed.

And that means repeating that simple mantra everywhere you can: “Only those who believe they are infectious would wear a mask now. It’s irrational to do so otherwise”.

Good point, will make it every chance I get

Trisha Greenhalgh (mask fanatic “expert”) has been wearing a face covering for months and months. I asked her on Twitter whether she considered she had had a case of infectious Covid-19 for this whole time and was promptly blocked.

Here in New Zealand with strict border controls and no community “cases” we have legislation requiring mask wearing on public transport, from one end of the country to the other, including isolated towns and islands. If there ever was a case for there never being signal for the cessation of this requirement this is it. The “just in case” scenario is beyond ridiculous.

Masks have nothing to do with health, only with control, obedience, identifying and ideally punishing dissenters.

They are Gessler hats, nothing else.

As such, all kinds of manipulations of science and information is justified with them.

In Germany, they have now gone full Orwell: Maske macht frei. Impfen macht frei. Civil rights are only for the vaxxed. An unvaxxed and untested aka healthy person is now dangerous and sick. The reason for Germany falling in the freedom of press League table is attacks on journalists by anti Corona restriction and pro civil rights demonstrators, not the the attacks, censoring and diffamation on and of them. And so on.

Not sure about “Maske macht frei. Impfen macht frei”, certainly such words would not be used in Germany. But it is the case that Germans, along now it seems with most other nationalities, are susceptible to intensive propaganda and will accuse those who question the new norm of being anti-social (at best).

Anyway, words on the LS sight don’t really do much to persuade people that they are actually being repressed, so in the spirit of fighting back in whatever way you can this piece of reverse proganda might be of interest to any Germans reading lockdownsceptics. As any translation program shows it is written for children but with the message clearly aimed at parents and adults. And don’t forget: VERTEILEN MACHT FREI!

KINDER! WEHRT EUCH!

DIE WOLLEN EUER SPIEL VERDERBEN!

Weißt Du, dass Deine Körper aus winzigen Zellen bestehen und dass einige davon T-Zellen genannt werden? Weist Du, dass Deine Thymusdrüse Deine T-Zellen trainiert, um Dich vor Krankheit zu schützen? Nein? Dann lass es mich erklären.

Genau wie Deine Arme oder Beine, ist Deine Thymusdrüse, wir nennen sie TD, ein Teil Deines Körpers und die Aufgabe von TD ist es, Deine T-Zellen zu trainieren, sodas sie verhindern, dass Du krank wirst. TD muss wirklich schlau sein, denn jede T-Zelle hat eine andere Aufgabe, wenn sie Dich schützt.

Genau wie in der Schule, wo einige besser Deutsch, andere besser Sport und andere besser Mathematik können, werden Deine individuellen T-Zellen so trainiert, dass sie Dir helfen, wo sie am effektivsten sind. Einige Deiner T-Zellen bekämpfen jede Krankheit, andere erinnern sich daran wie der Kampf gewonnen wurde, damit es beim nächsten Mal leichter ist die Krankheit zu besiegen und einige sind da, um Dir zu helfen, Dich nach dem Kampf sanft zu erholen.

Also, Du kannst sehen, dass die TD sehr wichtig ist, um sicherzustellen, dass Du ein gesundes Leben führen kannst. Damit die TD gute T-Zellen trainieren kann, muss es auch trainiert werden, und dies geschieht durch viele kleine Kämpfe mit den Dingen, die für Dich schlecht sein können, Dich aber nicht wirklich krank machen würden.

Und das ist jetzt der beste Teil, denn nur Du kannst helfen die TD zu trainieren, indem Du zum Spielen augehst! Denn je mehr Du mit Freunden spielst, auf Bäume kletterst, Dich schmutzig machst, Würmer isst, oder was auch immer, desto besser wird TG Dich beschützen! Und wenn TD stark ist, brauchst Du weniger unangnehme Medizin und Spritzen!

Aber wenn Du alleine spielst und eine Maske trägst, lernt TD nicht, wie man gute T-Zellen herstellt und kann Dich nicht so gut schützen.

Wie Du weißt, spielen wirklich nur Kinder. Und tatsächlich muss TD das meiste lernen bevor Du erwachsen wirst, sonst wird es Dich nie so richtig schützen können. Also tue etwas für TD, wirf Deine Maske weg und

SPIEL MIT DEINEN FREUNDEN!

These words have actually been used by German politicians, first and foremost Markus Soeder.

If anyone doesn’t speak German it is saying that the thymus gland is important in children because it teaches the T cells to fight disease. And to fight disease children need to play together and if you wear a mask your thymus won’t learn to fight disease. I’m not sure I quite agree with that as the mask doesn’t really do much to protect children, I even have a sneaking suspicion they help spread the germs about. But it is an important lesson nevertheless. If we grow up in a sterile environment our immune systems will never develop properly.

I must admit I’d draw the line at eating worms. Raw milk maybe…

well it serves them right…. any nation that cant come together against tyranny deserves to suffer the consequences. you reap what you sew dont you? Those that blame politicians and the media are just looking for an easier alternative than blaming society as a whole… it is society that allows or wont allow.

No you don’t! You reap what you sow.

On the bright side, no one wears a mask anymore when outside at the private school in Sussex I pass through daily.

There clearly is reverse herd instinct and peer pressure now, especially since the return post Easter.

And I witnessed the same for the very first time with a sports event on TV yesterday: there was hardly a spectator wearing a mask to be seen at the last round of the Valspar Championship in Florida yesterday, in contrast to the three prior days there!

(I am convinced the TV guys have and followed instructions to try to show as few unmasked people as possible at these golf and other events sofar.)

Agreed, I’m seeing far fewer pedestrians wearing masks between shops than there have been in the recent past. It’s probably 1-2% now, down from maybe ten times that. People are still fully compliant in the shops but they are now doing the minimum to comply with the rules.

That is exactly what I have found too.

Please don’t use the word compliant. There are several better words, surrender, stupid, virtue signalling (forgive the mix of tenses).

For some reason I can’t edit my other post. Please don’t forgot non mask wearers are also ‘complying’. Exemptions are very broad.

There is a ten minute window for editing and you cannot edit at all once your comment has recieved a reply.

I went to local garden centre yesterday, early to avoid the large queues. Who wants to spend all day waiting in them? Anyway, everyone in the small queue ahead of me were wearing masks, I joined maskless and noticed a guy ahead taking his mask off now that he had ‘reinforcements’. I’m glad I gave him confidence not to wear it, I only hope that when I’m not there the next time he has to queue he feels brave enough to do what he wants to do. He did however put it back on when he entered the garden centre. Small steps I suppose.

This is why I wish more of our fellow sceptics would avoid going all out online shopping*, we need to give each other as much support as possible in situations like that, not to mention local businesses that are struggling but compelled to obey bozos dictats.

*Not that I blame those that do in order to avoid conflict but in my experience and that of others here, such confrontations are vanishingly rare even if the press did try to promote them for a while last year.

my take on it is that considering what me be coming down the line of Mike Yeadon’s doomsday scenario is to be believed we should all take every opportunity to get out and about – shopping – eating out etc while we can before the vaccine passports come in and mean we are excluded.

Milo, well yes, but I’d recommend we do a great deal more than go shopping!

It’s a matter of fact that, at present, there’s no database containing a digital ID in common format with an editable field which is part of an interoperable system.

When everyone is coerced onto such a platform, and they will be if the system starts up with a bare majority of adults on it, we will have no freedom to refuse instructions or right to do what’s prohibited.

That’s totalitarian tyranny, with no exit.

As to the purposes that power will be put, who knows?

Totally agree. And to keep physical cash in the economy too.

It’s not against the law to pay in cash but they want us all to pay through these apps!

Whichever study (ICLs??) they quoted at the last press briefing when they stated they work was a heavily reduced version of the executive summary. This stated that they had to be of the right material worn in the correct way etc. The conclusions of the same paper were at complete odds with the summary, little evidence to show reduction in transmission, scant evidence to indicate any protection.

It’s not science its just nonsense from the ‘experts’ in charge who are enjoying the power far too much.

On the plus side when a 15 year old calls you a liar you can override the body language and use a bit of cloth to hide the hole the lies come out of.

This is so normal it is unremarkable.

Some years ago I did this same exercise with Climate Change papers. They often came to conclusions which were the precise opposite of what was claimed for them.

Scientific papers are now routinely commissioned to provide justifications for activist policy decisions. Essentially, the massive provision of government grants to support scientific research since WW2 means that science has become completely politicised…

climate change is big techs move to make the world greener… in other words to make themselves richer and more powerful because effectively green means more people stuck at home consuming social media and buying online. especially since now everyone has more cash left over since they cant travel go to bars etc

Ad on TV last night. Carlsberg is planting sea grass on floor of ocean because it neutralises environmental impact more effectively than a rainforest. They think it probably makes their beer taste better.

Nutrition is another bias-prone field where you have to check references carefully because their conclusions can be the opposite of the claims in the referencing paper.

There’s no doubt that the Fascists want face knickers for ever. This from the news round-up:

Professor James Naismith of Oxford University … argued that face-mask wearing could become a useful measure for countering diseases other than Covid-19. “I think we’ll re-impose masking in the winter on crowded indoor spaces. It has the benefit of reducing flu.”

So we’ve managed to live with flu since mankind was invented, and all of a sudden it requires universal knickering.

Sod off, Nay-smith, back to your nasty, snivelling, totalitarian hole.

It has the benefit of reducing flu ? Despite all the actual research conducted over many many years that they don’t stop flu transmission?

Face coverings were tried in the 1918 flu pandemic and did absolutely nothing.

He credits the Mask for eliminating the flu, reasonable people credit the Covid statisticians.

Like in January/February when PHE detected not a single case of flu as the Covid ‘Second Wave’ slaughtered the innocent.

Can’t have it both ways Naismith.

In my 48 years, a lot of time working in a customer facing environment, I have never had flu and seldom a cold.

Why should I start wearing a mask to avoid getting flu, which I am unlikely to get?

But the few weeks wearing a surgical mask at work made me anxious, stomach upsets and lack of concentration.

So some unelected, unknown Adviser just has to say

“I THINK” and that’s enough for

“We will re-impose mask wearing . . .”

Who the fuck is ‘WE’ ?

A large, multi centre study of transmission of influenza-like illnesses was made in Vietnam. No effect of masks.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4420971/

The government is weak and a mess……..

I will be voting against this socialist fascism, against all three main parties and particularly against any daffy ‘green’ party, and for any independent candidate with no links whatsoever to government/NHS socialist fascism.

That doesn’t leave a lot of choice…

It is the only choice.

We have some excellent local independent candidates.

And a big celebration in order after so voting!

This complete weird out orchestrated by the biggest bunch of complete nincompoops ever to take power in this country has to be voted down again and again and…….

Good luck with that – the average person who watches the BBC likely thinks Boris has done a good job handling ‘pandemic’, or that Starmer would do a better one and will vote Tory or Labour accordingly. Much though we really need a change in this country and a surge in those prepared to vote for the independents I don’t see them making much of a dent in the mainstream party votes.

There isn’t a single alternative candidate standing in any ward in my constituency.

Might have to write “NONE” on the ballot paper.

Ron DeSantis is a Conservative worth that name.

Notice his recent ban on vaxx passports and any discrimination of the people by corporate fascists.

I contrast, Boris Johnson is a narcissistic, spineless, fascist, corrupt and woke puppet and a true enemy of the people.

Ron is a Trump ally – would imagine that there is a hotline from the gubbernatorial mansion to Mar a Lago. If only Ron’s approach could cross the Atlantic.

I hope he has good close protection.

Dr Stephen Karanja was just murdered in Kenya. Allegedly dying of covid19, this is extraordinarily unlikely as one of the leading exponents if Pharmacological treatment.

He uncovered the earlier sterilisation attempts via vaccination & helped boot Gates out of the country.

Another great article from Will, and worth bookmarking.

A little while ago, before covid, I found the same thing in a medical paper – all seems plausible and even persuasive, and then you follow up a couple of references and you find those references do not actually say what is being claimed, or really have anything much to do with what is being claimed. But they do of course make the paper look authoritative.

The level of dishonesty in science is something to behold.

And the level of cowardice and stupidity in the population in following the mask mandates is also something to behold.

Good job I’m exempt.

I agree with this 100%, but come on, how many people can be bothered to make the effort? Even politicians just read the ‘ABC for toddlers’ summaries. Where I live people routinely wear masks outside and even two primary school kids I saw at the weekend were playing outside with the damn things covering all but their eyes. Their parents must be so proud…

Agreed, Wills excellent article confirming what we already know about masks is way way too long to be of any use in trying to convert a zealot.

Even previously sensible people refuse to look at the evidence and instead send that stupid cartoon of people pissing on each other.

Time to restart the triple underwear meme, to prevent rectal exhalation of the Covid, complete with Compliance Marshals.

A lot of investments into mask companies, we are cash cows and need to think of that every time we buy a mask. They stopped making plastic drinking straws and now make masks from polypropylene.

Buying masks? Why? I started by using an old jam strainer, then a bit of old lace, or a cotton rag with “masks don’t work” written on it, and I saw an excellent photo of a guy wearing a pair of underpants.

The greatest transmission risk has been the scientific nonsense spouted by politicians and their tame. non sagacious SAGE – the only individuals who should be forced to wear masks are the Politicians and media scientists and the masks should be soundproof!

I am genuinely astonished that most people still wear masks. I don’t wear one and I don’t get any hassle at all, not even a funny look from anyone.

I got escorted out of Meadowhall yesterday for not wearing one. My view is everyone is equal under the law including those politicians doing photo-ops the week before last. e.g. Johnson (twice in England), Gove (Israel), Starmer (Wales).

What happened to you your statement

‘I’m exempt, thank you?’

Unfortunately that does not necessarily make much difference if a shop or shopping centre choose not to accomodate people without masks. I do not wear one but if a shop manager refuses to serve me unless I have a mask there is little I can do about it other than boycott that particular outlet or establishment. However, this has never happened to me as most shops would rather have the custom as opposed to being anal about face coverings. I see the manager on the shop floor of my Tesco Extra every week and he sees me but he just looks the other way. As many others have mentioned, I have never been challenged either by staff or members of the public for not wearing a mask. Quzzical looks is about the limit. I appreciate there could always be a first time but so far, so good.

If they refuse to serve you then you have the option to sue them for discrimination.

I agree and most (certainly the big chains) will know that which is why nothing is said. A poorly paid and informed security guard in a shopping centre probably does not know that.

Large retailers and Security companies were fully informed of the law and with few exceptions abide by it (the Police were worse to begin with).

The individual security guard is wrong in law and his employing security company and their client could be liable for damages.

On the first day of compulsory mask wearing I went to my local convenience store early and when the owner pointed at his new sign I very politely informed him of the law relating to exemption and that if he challenged it he himself would be guilty of Disability Discrimination.

I then forwarded him the PDF from the lawnotfiction website outlining this in detail.

Good for you, retailers might as well say they won’t accommodate blind or black people.

Why are we still going on about the effectiveness of masks? It has been proven that they are useless in preventing transmission, the data tell us that. They are however very effective in proving compliance.

Because they’re still being required, even after the June lifting of restrictions.

There’s James Max on Talk Radio still promoting restrictions and masks because of VARIANTS!! and what if this, what if that.

He was also talking spherical objects about electric cars, eulogising about them to Quentin Wilson as they both admitted to being I-pace owners (starting price £65K).

I read somewhere reputable online this morning that Musks Tesla eclectic car company has a stock market valuation worth more than the rest of the auto industry combined.

Might be his investors know something we don’t but then again it could be Tulip Mania revisited.

Because they will represent the last bastion of “control” that will be left after the restrictions which the data no longer justify have been lifted – they will be the last remaining link to the fact that we are under government control and a vital psychological tool. Always important to keep that tiny little bit of fear bubbling away in the background so that it can be manipulated again when the time/need suits.

I turned him off. Idiotic wanker.

That has always been the case as was repeatedly pointed out here at LS when they were introduced last summer at a time when any efficacy they might have was rendered pointless as Covid had gone on its summer seasonal holidays.

Another great article Will. The lovely Dr Sam Bailey on YouTube rips a lot of these so called scientific papers to shreds especially on the useless Wikipedia. All the so called science this government has based its mandates on is utter bollocks. I read yesterday all the covid in the world could fit into a coke tin and you think your poncey black mask is stopping that? Like hiding from a high powered rifle behind a chain link fence. It’s just virtue signalling of the absolute fear this government has spread. Especially the young. Wanna know why masks are useless. Go back to last March, remember, death is knocking at your door. Meanwhile in supermarkets the staff are all working unprotected with hundreds of thousands of disease carrying people sneezing and coughing all over the goods. How many supermarket workers died. Surely all of them right. The body bags must have been piling up. They had NO mask, NO perspex screen. It will take a long while to get people out of wearing masks, what a bunch of uneducated sheep, they get all the sickness from wearing a mask and still come back for more.

Thanks for the Sam Bailey reference. That’s a real Kiwi accent!

Agree with what you say apart from the Coke can bit. I read that yesterday. It’s a graphic concept but how do we know how many ‘Covid’ particles there are in the world. There are many verifiable arguments against masks without leaving ourselves open to Covidiots picking on the one unverifiable claim.

Back last Autumn the weekly 15 minute BBC R4 numbers programme (weekday 09.45 ‘the sum of it (?)’ reliably informed us that all the Covid in the world would fit into a large wine glass.

My Bank Holiday W/E NHS adventure

(Gets on topic in the end).

On Saturday my pharmacist told me that a crucial repeat prescription was not on their system; knowing that my supply would run out because of May Day I called 111 who advised that ‘County Doctors On Call’ would be able to issue an emergency one that day.

County Doctors rang me and arranged an appointment for that afternoon at their location on a trading estate nowhere near the hospitals, or indeed a Saturday bus route.

I had to wait outside in the taxi until telephoned to enter, sat on a little chair in the middle of a portacabin for a coursery examination by a doctor in full Covid Safety gear.

Never mind, I got the scrip I wanted which was all I cared about, plus two others which I knew I didn’t need.

To my surprise that same doctor telephoned me while in the taxi back to town to tell me she was concerned about something else and that I should present myself at the main hospital (Medical Triage part of ITU) asap. Having collected the scrip I actually wanted, my taxi driver eventually dropped me off at the main entrance.

Following an examination the consultant ‘politely’ dismissed the County Doctors fears but wanted me to stay overnight relating to a pre-existing condition.

(I had no phone charger so kept internet access to a minimum).

Every four hours they took temp, blood pressure and pulse tests for the 6 people in my bay plus one Covid test.

Shortly before being discharged on Sunday afternoon a nurse knelt beside me to tell me the ‘bad news, sadly you’ve been exposed to Covid 19 here in this bay, so unfortunately when you go home later you will have to self isolate for ten days’.

I didn’t bother arguing about false positives or the almost total lack of Covid in the County for many weeks.

She asked how I planned to get home and when I replied ‘by taxi’ she said

“Ok that’s fine, just make sure you’re wearing your mask for the journey”

and the same to a fellow patient who was going home 10 miles away by bus !

Does that mean they really do believe in the abracadrabra power of masks to prevent a potentially contagious passenger infecting his driver, or fellow passengers, or is it because they know it all complete bollocks but just have to go through the motions.

Yours truly is thus now self isolating after an uncalled for overnight in the hospital having spent 12 months out and about as a ‘key worker’ up close and personal (mask exempt) with approx 6,000 random people ever since day one of Lockdown.

(sorry for the length of post, I left much out which might be of interest but entirely of topic).

Any symptoms?

What a nightmare for you. From just trying to get a prescription, to an overnight hospital stay, to isolation for 10 days! Wow. I have some health issues which I have to be routinely monitored for and it all feels like such a pantomime performance now, that they want you to go through, to keep up this illusion of an on-going pandemic.

If the population was an aircraft and mask-wearing was needed for flight, then the evidence presented so far would not get you an airworthiness certificate from the CAA, FAA or EASA.

I’m professionally qualified engineer, working in product safety and if I presented this level of non-evidence to my sector regulator to support my product’s safety argument, I’d be laughed out of a job.

Aha, but you deal in realities.

the article makes the important mistake of assuming you actually need evidence to get people to believe you

The high priests have declared the mask to be the holy relic. All praise our great leaders.

Firstly, masks must stay, because they are The Badge. Then, in order to turn the vaccinated against the unvaccinated, a visual symbol will be needed; how can you tell whether to bully someone based on a digital ID that’s in their pocket? No, in Project Yellowstar, The Badge will be used to separate the Virtuous from the Verminous – got your vaxport, no mask needed. No vaxport, compulsory mask wearing, 24/7, no exemptions. Cue lynchings etc.

That might work now but when cv21 turns up and everyone has to wait 1-2 years for their next jab it might prove a little difficult to start lynching the unvaccinated.

I think the idea is that they don’t have to wait 1-2 years, they just add the new sequence to their mRNA vaccine and it’s ready for distribution in 1-2 months.

maybe but the queue is still around a year long unless they increase and maintain capacity for the actual jabbing.

Sorry 20 somethings, your summer holidays are cancelled because your new vax won’t be ready until Christmas.

and of course the above queuing is what all the smug zombies calling for a vaccination passport haven’t stopped to think about.

Indeed. And it doesn’t even need to be a vaccine.

There will he no clinical safety studies.

Once VaxPass is up & running, you’ll be instructed to turn up for such a top up.

There’s absolutely no reason for any top up vaccines.

Immunology is among my strengths, do I’m absolutely certain about this.

The repeated variants narrative is what showed to me the mode whereby depopulation will probably be accomplished.

Someone asked me what it felt like travelling on buses and trains, the only one unmuzzled. ‘Miserable’ probably sums it up best, despite a sense of superiority.

I see the government now intents to keep the stupid things going after 21/6. It won’t make any difference to me as I refuse to wear them. If businesses won’t serve me without one then they’ll have to do without my custom.

Do you ask to see the owner and tell them? Makes no real difference to an employee, but it may make the owner think twice.

I told the manager (who I knew by sight by virtue of long term custom) of a local Toby Carvery why I would not be back for a while after being confronted at the Meet & Greet point by a staff member who declared “No QR Code No Service!”.

He was wearing a mauve waistcoat with matching mauve mask which I imagine he crafted from the worn seat of his trousers which made his tone worse.

This article bends over backwards to be ‘fair’.

O.K, I can see why. The rational side in this argument shouldn’t be aping the unscientific distortions of the government – and should show clear rationality.

However, starting from the WHO strategy document of 2019, reviews of available research have shown no convincing case for the wearing of face masks when put into a scientific/medical context.

Consider :

(1) Scientifically, you have to show in probability terms that there is consistent evidence that masks have a beneficial effect. Not ‘maybe’ or ‘perhaps’, but convincingly. Otherwise the null hypothesis stands as the current conclusion. No ‘ifs’, no ‘buts’.

(2) In terms of medicine, this theoretical principle turns into a very practical one. Any treatment has to show that benefits outweigh the harms.

Mask wearing doesn’t pass these criteria by any stretch of the imagination, and the idea should have been binned before it started breathing (!) again.

Yes indeed, regarding 1) if the medical establishment and Wikipedia were to follow their normal policy on reporting medical interventions they would be saying “There is no evidence that masks help”

I’ve noticed the same in many Climate Science presentations. They will cite a paper as backup for a proposition, but when you go to that paper it will just mention the idea in an aside, as a piece of speculation, without any supporting evidence. They just rely on no one following up. The IPCC summaries are, through the same process, unmoored from actual scientific research.

“It’s just a piece of cloth”

If you agree to mandating triviality then you are probably incapable of making decisions for yourself.

Excellent article Will. I appreciate the time, thought and effort you put into LS and your articles are one of the main reasons I keep visiting this site, ATL in any case. These articles about the effectiveness, or lack thereof, of masks are still highly relevant, particularly for people like me where the rules around wearing masks at work (a non-medical nhs setting) have just got stricter despite “case” numbers being on the floor, and people are being threatened with disciplinary action if they repeatedly “break the rules”. Twice weekly LFTs have just been introduced (voluntary so far), so I felt compelled to email managers’ attention to the fact that the government’s own literature says that when caseness is so low as it is presently, a positive result is likely to be a false positive. This gov document was attached to the email inviting us to participate in LFT testing, FFS! No surprise there’s been a deafening silence in response to my email. Time to give them a nudge!

I guess my point is that it’s good to have as much evidence up your sleeve as possible to highlight the idiocy of these mandates and directives – it might come in useful some time!

Thanks for that. I too work in a non-medical nhs setting. I have refused LFTs when offered to me before. If a similar email comes my way I will look out for the document and do the same.

Everything this disastrous government has done from the start has been weak and a mess.

With the exception of its fear mongering propaganda of doom and gloom which succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

I went to an open air market today – lovely sunny day, lots of people there looking for bargains – still quite a few wearing masks though – overheard a few of the sellers and buyers discussing their vaccinations and the subsequent side effects – some thought the first jab had the worst side-effects and others thought the second with one complaining that his arm has ‘not been right‘ since he had the jab over a week ago. One mask-wearing seller claimed that he has not allowed anyone to touch him for a year (how true this is I don’t know?) – but when someone bought an item from him he held out this long wooden stick with a plastic tuppawear container stuck to the end for customers to put their cash into afterwhich he then proceeeded to wash his hands in sanitizer.

Just a snapshot of the kind of insanity I am witnessing from my part of the world – if this is anything like the rest of the country then we could in this insane situation for the long-term.

I’ve not seen that since during lockdown 1. when I went to a newsagent that I rarely use. They had a trestle table on the pavement barring entry to the shop and various felt tip signs giving instructions.

I paid by credit card through the door glass rather than leave cash in the little tub labelled “put cash here”.

He then opened the door just enough to squeeze his gloved hand out and tossed my cigarettes onto said trestle table.

Needless to say I have not been back since.

Hi all . . . I’ve started a collection of mask-related papers (probably bitten off more than I can chew, as i’ve a-many other things to do), but an early point of interest – backed up by the papers quoted in this article – is somewhat revealing:

All – as in ALL – the papers that have come out in favour of mask mandates are from 2020 or 2021 (mostly after mandates were imposed). Papers from before 2020 lean heavily towards NOT recommending masks/face coverings. ‘Emerging science’? Hmmmm . . . .

Which isn’t to say that there aren’t papers from 2020/21 that do not recommend them (eg the Danish study), or which highlight the potential & actual harms, but they are ignored (of course).

Yet another big red flag. . . .

Galileo recanted his heresy about the earth revolving around the sun to avoid being burned at the stake.

Same principle really.

His final words were said to be

‘Yet still it turns’.

“The best quality evidence (which isn’t saying much here) is five RCTs where all members of households (ill and well) wear masks, which indicate masks may reduce risk of infection by 19%”.

It also doesn’t allow for the known fact that the entire household is unlikely to catch or develop Covid-19, masked or not, so any apparent results would indeed be pretty useless. (as are masks!)

… given that in-house transmission is estimated at only 17% anyway.

Thanks, Rick, I couldn’t remember the figure but knew it was very low.

And that only if the source was symptomatic,

If the potential source was asymptomatic, the secondary attack rate was 0.7%.

By attack, is meant the contact became PCR positive, yet on NO occasion did that contact become symptomatic.

As 0.7% would be a good lower bound for operational false positive rate, I think even to become PCR positive is a ZERO risk if you share inside space with a person lacking symptom.

That on not a single occasion did a contact become positive & symptomatic ie ill, yet again confirms a zero risk of transmission inside, sharing space closely with others, provided no one is symptomatic.

This is what we’ve known for centuries & is why we’re very good at detecting symptoms of respiratory illness in others.

The answer is to make them non compulsory. Those who believe they do any good are free to continue in their belief.

they tried that and naturally only the insane were wearing them. Then they invented the “it’s to protect others” crap because masks are magic and only work in one direction so now the insane have a reason to try and shame you into wearing one.

‘I’m wearing a mask to protect you’

was indeed a masterstroke worthy of Dr Goebbels no less.

‘I’m wearing a mask to protect you’

A shop assistant used that line on me. Said I was sorry to hear it, best go home for some rest etc.

No reaction, as usual.

I was asked in a general chatty email from a friend, ‘by the way, have you had your jab yet, just had my 2nd one’ as if its normal to give your medical history away in an everyday conversation, the country has lost the plot and its doing my head in.

I don’t think the ‘medical history’ issue is the main one – it’s the way brainwashing has generated this blithe assumption that a snake oil injection is quite normal – just like so many Germans in the 1930s just knew that Jews were a bit dodgy.

Thank you Dr.G for your insights into informing the public of what is necessary and in its best interests.

I’m so sick of that – one of these days I will lose it and challenge them for nosing into my medical history.

These psychotic politicians cannot believe that they’re still getting away with this b.s. Raab’s probably got a nice little bet on that the public will still wear their masks in the height of the Summer…

What an utter disgrace. It would be better if they all just went home and stayed there. These people need to be fired immediately. The so called ‘experts’ are nothing of the sort.

I’ve just completed a report on the health effects of wearing masks for the public and specifically for children. It knocks anything the SAGE clowns come up with into a cocked hat.

The list of ill effects from mask wearing are so long you will need around 40 to 60 minutes to read my report. You can download it from free and there’s a plethora of supporting documentation (PDFs) available in zip format.

https://www.grahamfrench247.com/useful-documents

I hope you find it of use.

Thanks Graham