Now that Chile is settling down a bit, the latest Covid cautionary tale is India, which never seems to be out of the news at the moment as its positive cases and deaths have rocketed in the past few weeks.

Even the usually level-headed Kate Andrews in the Spectator has been painting the situation in lurid colours.

As it happened, the UK’s worst nightmares were never realised. The Nightingale hospitals built to increase capacity were barely used. But what the British Government feared most is now taking place elsewhere. India is suffering an exponential growth in infections, with more than 349,000 cases reported yesterday, as well as nearly 3,000 deaths. Hospitals are running out of oxygen for patients and wards are overflowing. There are reports of long queues as the sick wait to be seen by medical professionals. It’s expected the situation will deteriorate further before it gets better.

Jo Nash, who lived in India until recently and still has many contacts out there, has written a very good piece for Left Lockdown Sceptics putting the current figures in context – something no mainstream outlet seems to have any interest in doing.

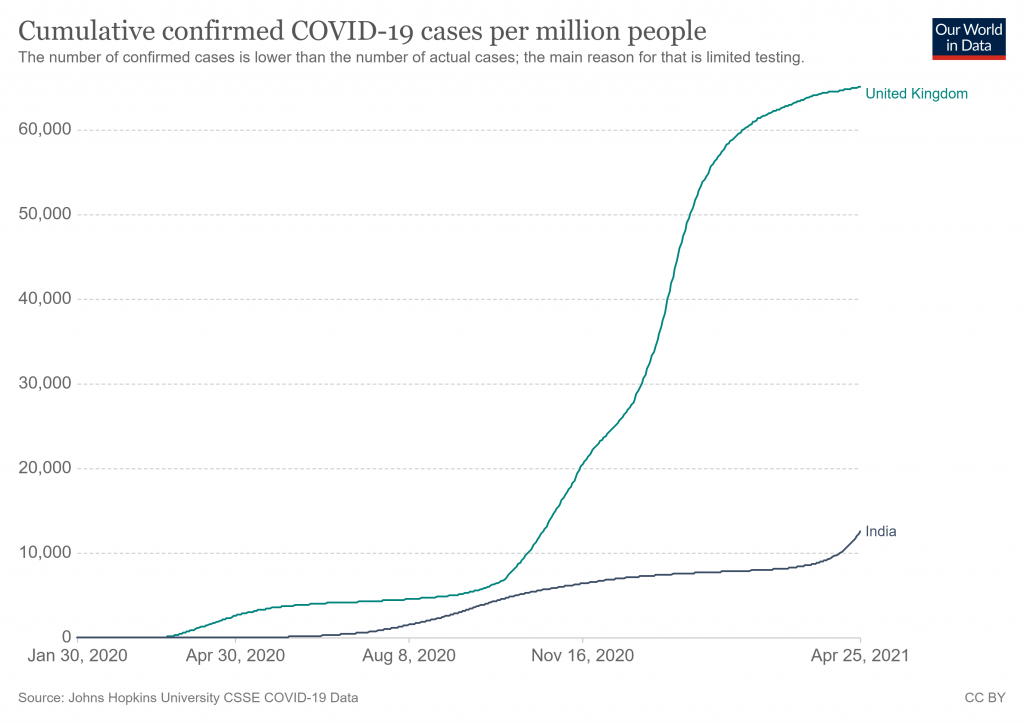

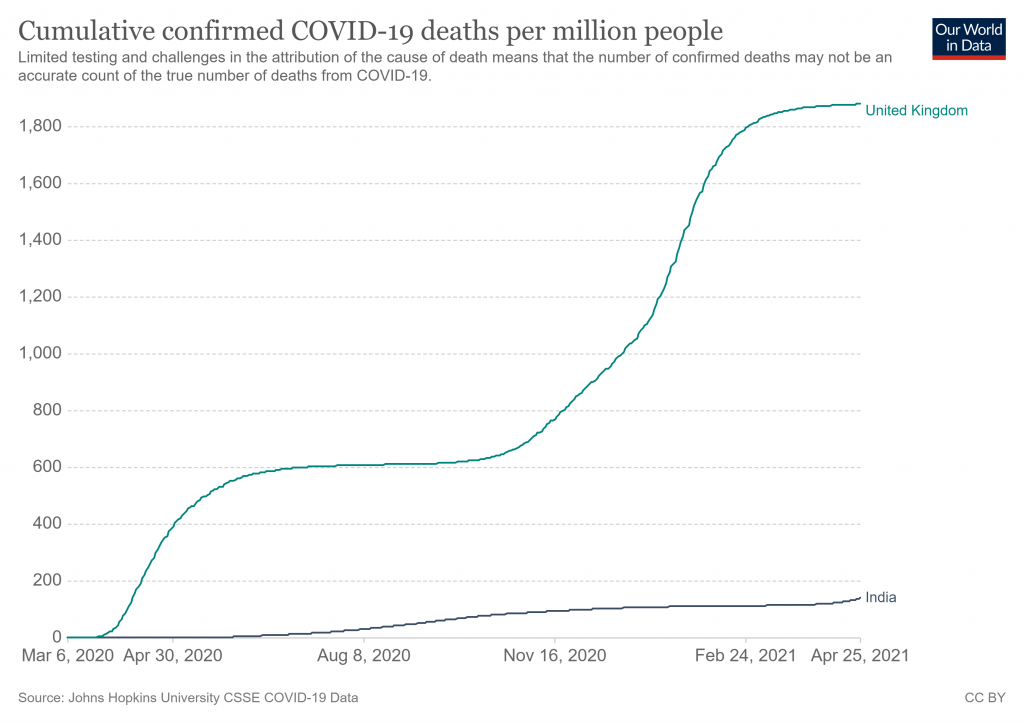

Jo makes the crucial point that we need to keep in mind the massive difference in scale between India and the UK. At 1.4 billion people, India is more than 20 times larger than the UK, so to compare Covid figures fairly we must divide India’s by 20. So 2,000 deaths a day is equivalent to a UK toll of 100. India’s current official total Covid deaths of approaching 200,000 is equivalent to just 10,000 in the UK.

In a country the size of India and with the huge number of health challenges faced by the population, the number of Covid deaths needs to be kept in perspective. As Sanjeev Sabhlock observes in the Times of India, 27,000 people die everyday in India. This includes 2,000 from diarrhoea and 1,200 from TB (vaccinations for which have been disrupted by the pandemic). The lack of adequate hospital provision for Covid patients may be more a reflection of the state of the health service than the severity of the disease.

Jo Nash also points out that poor air quality plays a role.

Delhi, the focus of the media’s messaging, and the source of many of the media’s horrifying scenes of suffering, has the most toxic air in the world which often leads to the city having to close down due to the widespread effects on respiratory health…

Respiratory diseases including COPD, TB, and respiratory tract infections like bronchitis leading to pneumonia are always among the top ten killers in India. These conditions are severely aggravated by air pollution and often require oxygen which can be in short supply during air pollution crises…

According to my contacts on the ground, people in Delhi are suffering from untreated respiratory and lung conditions that are now becoming serious. I’ve also had breathing problems there when perfectly healthy and started to mask up to keep the particulate matter out of my lungs. I used to suffer from serious chest infections twice yearly during the big changes in weather in India, usually November/December and April/May. When I reluctantly masked up that stopped. My contacts have reported that the usual seasonal bronchial infections have not been properly treated by doctors afraid of getting Covid, and people’s avoidance of government hospitals due to fear of getting Covid. Undoubtedly, these fears will have been fuelled by the media’s alarmist coverage of the situation. Consequently, the lack of early intervention means many respiratory conditions have developed life-threatening complications. Also, people from surrounding rural areas often travel to Delhi for treatment as it has the best healthcare facilities and people can go there for a few rupees by train. This puts pressure on Delhi’s healthcare system during respiratory virus seasons.

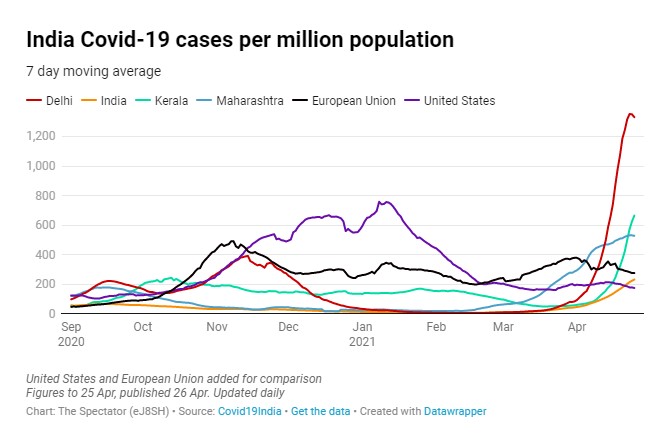

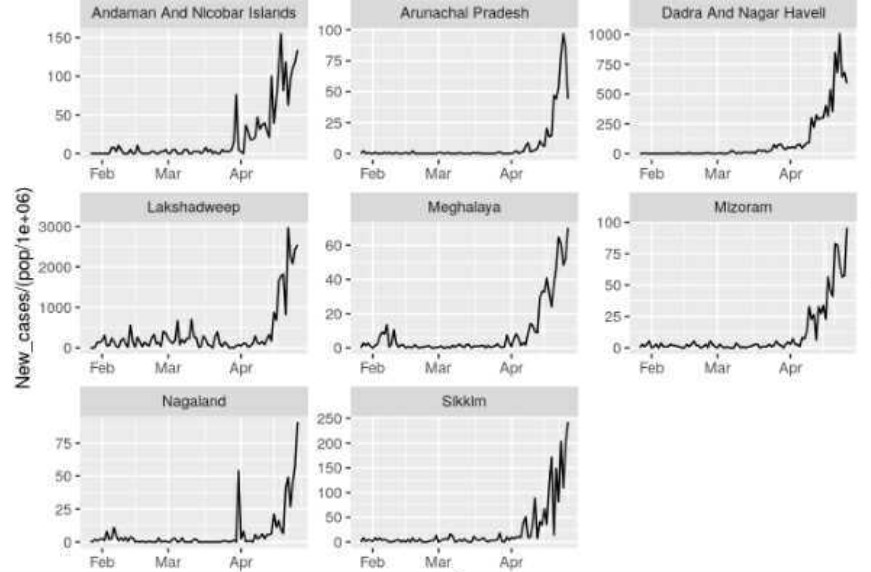

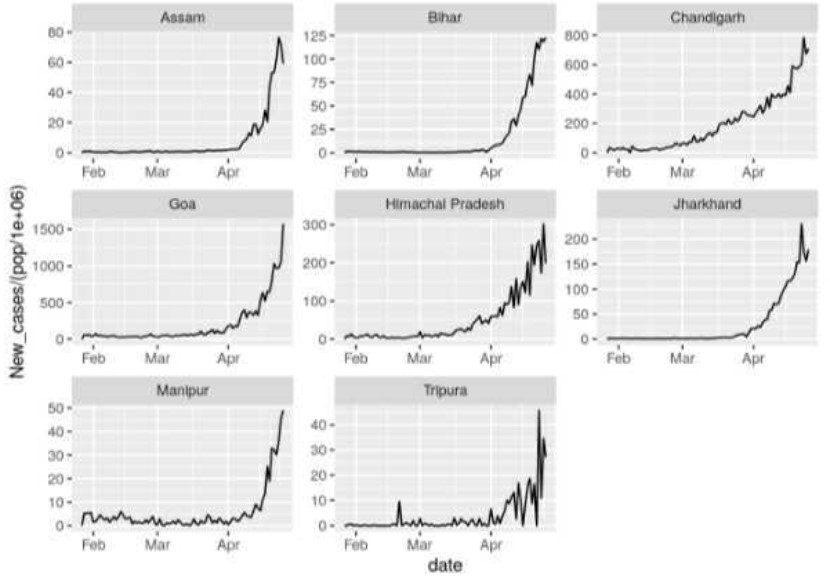

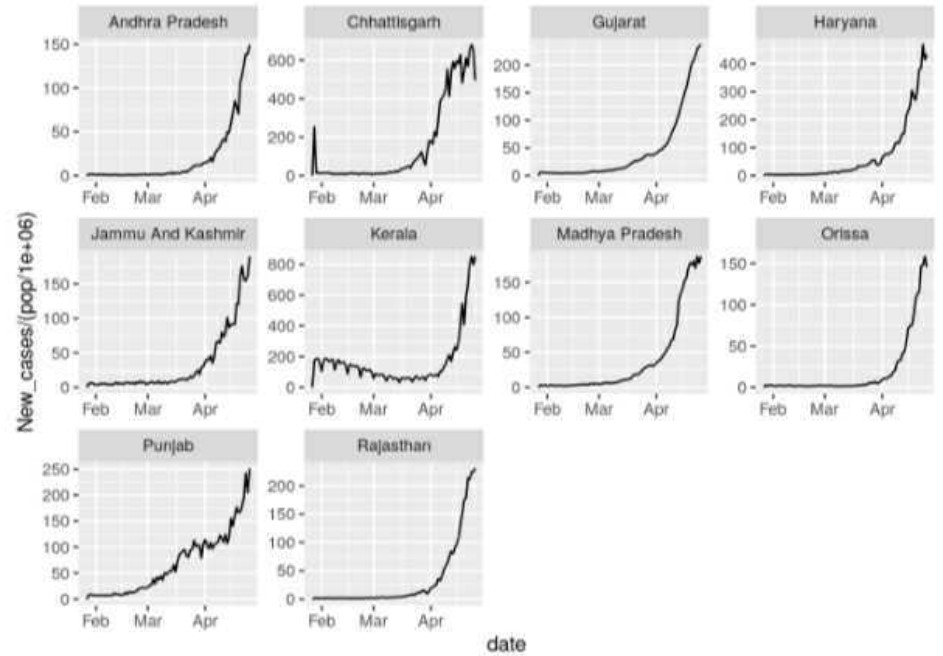

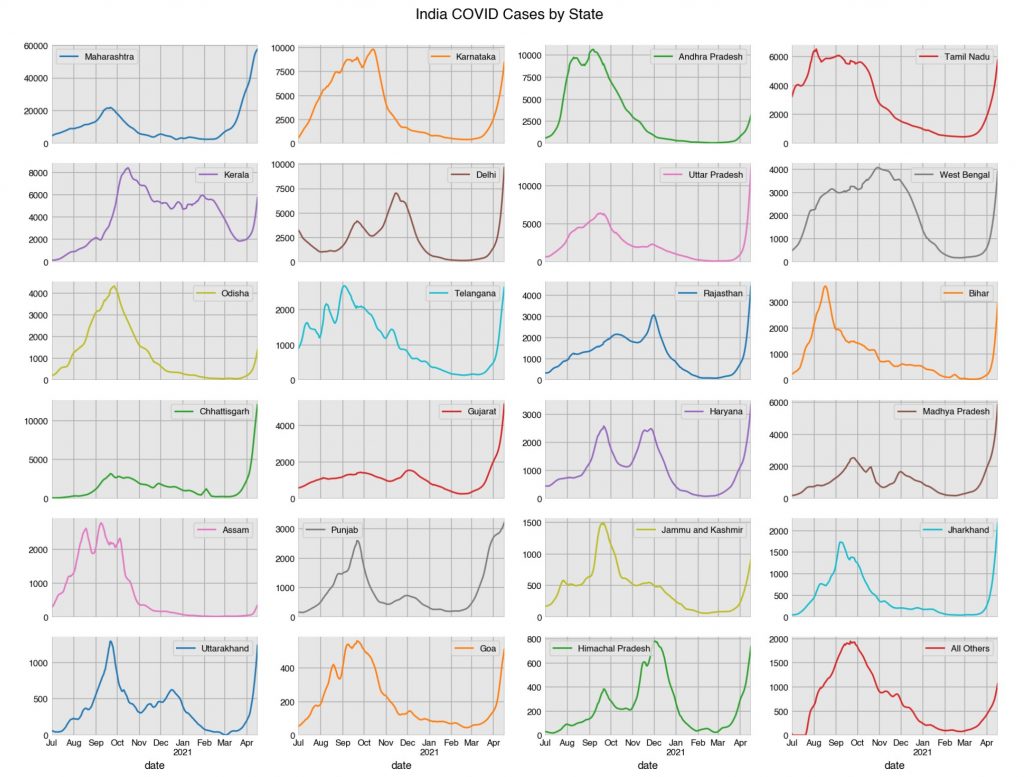

Positive cases look like they may be peaking in many regions now.

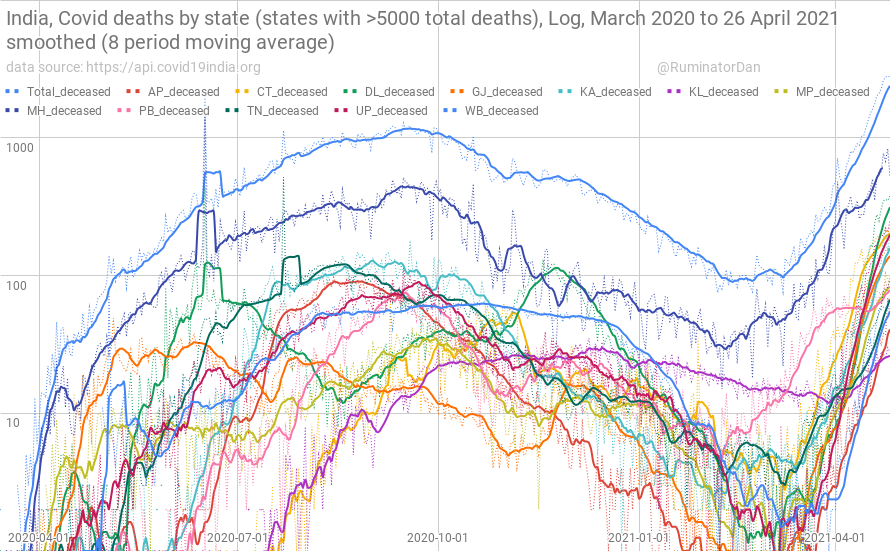

One mystery, as yet unexplained, is why India, which has not experienced a strong surge like this so far, suddenly did in March and April. Adding to the mystery is that the simultaneity of the surge across the regions is unexpected in a country as large as India and contrary to earlier outbreaks last year. Nick Hudson from Panda suggests it means there must be something artificial about it as it is not a natural pattern, since viruses naturally spread across the country with some delay and variation evident between regions.

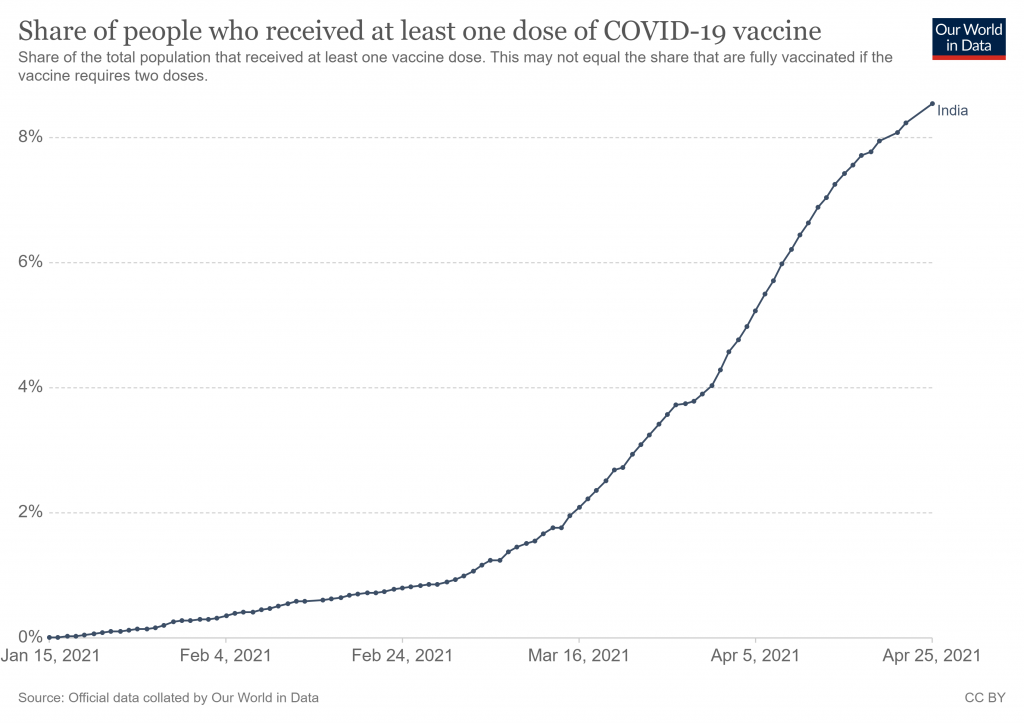

It hasn’t escaped people’s attention that one novel factor is the nationwide vaccine programme rollout, beginning in January and accelerating during March. Is this a further example of the post-vaccine infection spike seen in the various trials and population studies, possibly caused by temporary suppression of the immune system?

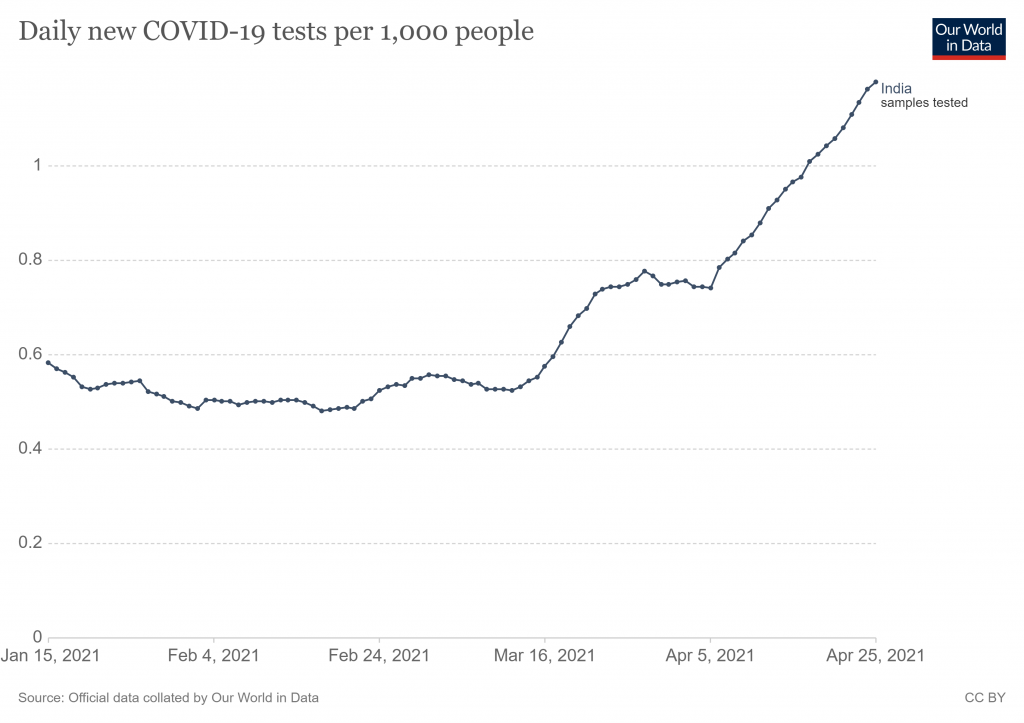

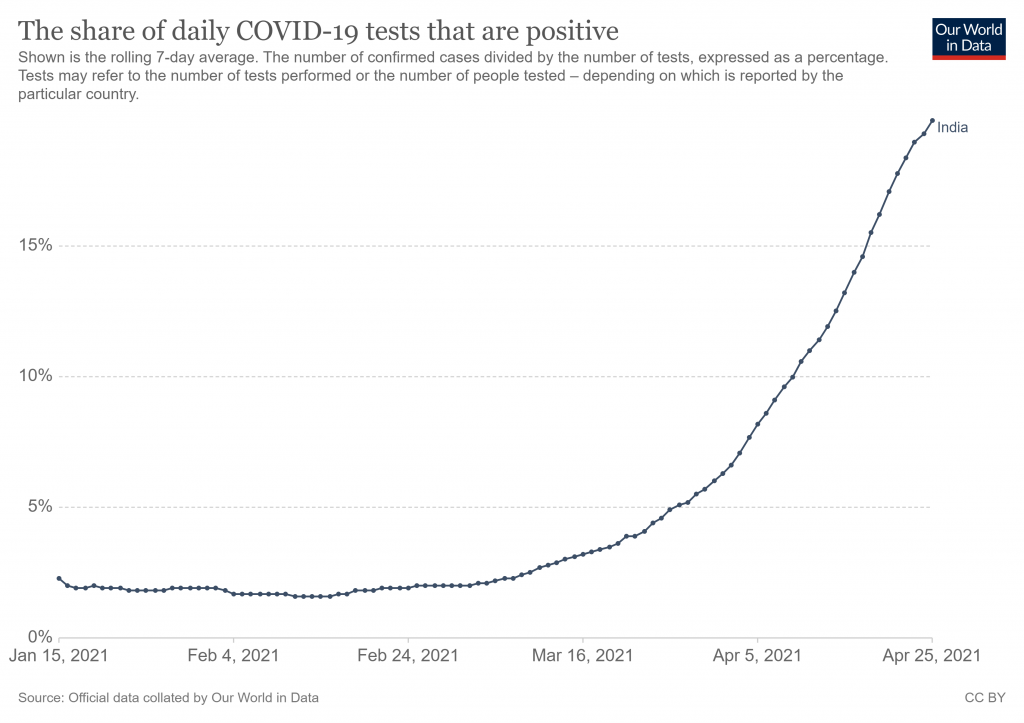

Testing is another possible factor, as the number of tests being carried out surged in March and April – though so did the positive rate, suggesting this can’t be the only explanation.

Whatever is going on, it’s a pity there is not more curiosity among our scientists and journalists. Instead, it’s just the usual scaremongering driven by the misrepresentation of data.

Stop Press: Former Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations Professor Ramesh Thakur has been in touch with a comment he left on a story in the Australian.

Some context and perspective. India’s Covid deaths yesterday were 2,163 (seven-day rolling average). India’s average daily death toll is 25,000 from all causes.

Second, despite this surge, as of now India’s Covid mortality rate is 140 dead per million people. This compares to 401 for the world average, 1,762 for the US, and 1,869 for the UK. It puts India 119th in the world on this, the single most important statistic for comparison purposes.

Third, the crux of the problem in India is not the proportion of cases and deaths from Covid. Rather, it is the lack of a fit-for-purpose public health infrastructure and medical supplies of equipment and drugs.

Fourth, although Government neglect of public health while prioritising vanity projects like a new Parliament building during the pandemic, building temples and statues etc. is a contributory factor, the real cause of a poor public health system is poverty. Put bluntly, poverty is the world’s biggest killer.

Fifth and finally, this is why a strong economy is not an optional luxury but an essential requirement for good health.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Dreams and wishes will result in our downfall!

Boris. You have joined GB News. Can you now admit since you are no longer in government and having to pander to the UN and WEF that GREEN policies and energy are in the words of David Cameron ——-CRAP.

Toby doing his best Rev JC Flannel impression on the baby-butcher fans flexing their muscles in our midst – ‘let’s try and educate them.’

Toby, that idea hasn’t worked out well for the last 1500 years. They just butcher more babies to horrify and terrorise everyone else into conversion or submission.

You can leave this problem to be confronted by your children or we can act now while we can. The West isn’t a suicide pact and illiberal measures are essential against our would-be conquerors.

Toby says that our Muslim citizens probably support British values. No they are Muslims first and british a very far second. Islam is a powerful ideology like communism. Communists always put the party first and country nowhere. Many Muslims want Britain to be taken by them. We will have to fight for our ancestral inheritance

Totally agree – Toby, yet again, for some strange reason, misdiagnoses the key problem, which is that Muslims detest our way of life at a fundamental, religious level, which means that integration into our society is simply not achievable. The status and role of women (and men) in society, the way women dress, tolerance of and respect for other religions and gay rights are some examples. Yet Toby argues that it is simply an issue of anti-semitism and / or wokeist anti-colonialism, neither of which are unique to Muslims.

Immigrants from other countries and cultures – Europeans, Hindu Indians, non-Muslims of African and Caribbean descent, Chinese, etc – do not in my opinion seem to have a fundamental problem with British or English values and culture.

My good opinion of Nick Dixon is enhanced by his appreciation of the Larry Sanders Show, which is up there with Fawlty Towers tho I skip the opening monologue.