I’ve previously explained why “we have to compare Sweden to its neighbours” isn’t a convincing argument for lockdowns. However, the argument keeps cropping up on social media. So I’ll have another go.

As I noted in my previous post, Sweden has had more deaths than the other Nordic countries – whether you use ‘confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people’ or age-adjusted excess mortality.

However, this doesn’t mean that lockdowns are what account for the divergent mortality trends. In other words, it doesn’t follow that if Sweden had locked down at the same time as its neighbours, then it would have seen many fewer deaths from COVID-19.

Even if you believe that lockdowns were the main factor behind the other Nordics’ low death rates (and they probably weren’t), the epidemic was already more advanced in Sweden by the time its neighbours locked down. And since lockdowns don’t have much impact unless case numbers are low (as in Australia and New Zealand), locking down probably wouldn’t have made a big difference.

Moreover, there’s good reason to believe that lockdowns weren’t the main factor behind the other Nordic’s low death tolls. Rather, the main factor was probably border controls.

Let’s examine what each country did during the first wave, using the Oxford Blavatnik School’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. (I will ignore Iceland, since it’s a small island in the middle of the Atlantic ocean, and its geographic advantages are obvious.)

Recall that the Blavatnik School’s database includes several measures of government restrictions. I will focus on mandatory workplace closures, mandatory stay-at-home orders, and restrictions on international travel (i.e., border controls).

Let’s start with mandatory stay-at-home orders. None of the Nordics had any days of mandatory stay-at-home orders during the first wave. (This is in contrast to the U.K., which was hit much harder than all four Nordics, and had a mandatory stay-at-home order in place between March 23rd and May 12th.)

Now mandatory workplace closures. Norway did introduce these quite early on March 12th. However, Denmark did not introduce them until March 18th – just five days before the U.K. And Finland did not introduce them until April 14th – more than three weeks after the U.K.

These comparisons reveal that the other Nordics did not lock down particularly hard or particularly early. Indeed, all three had less strict lockdowns than the U.K. (which saw many more deaths during the first wave). Finland’s success is particularly difficult to explain with reference to lockdowns since the country did not introduce any real measures until after the peak of infections.

Yet when it comes to border controls, there is a clear disparity with the U.K.. Finland introduced border screening on February 6th, and was followed by Denmark on March 3rd and Norway on March 14th. Denmark then imposed a total border closure on March 14th, and was followed by Norway on March 15th and Finland on March 16th.

Sweden did not introduce border screening until March 19th, and never closed its borders. The U.K. did not introduce any border controls during the first wave (as recommended by the Government’s scientific advisers).

Given that none of the other three Nordics had a particularly strict lockdown, their success mainly owes to strict and early border controls. While mandatory workplace closures may have had an impact in Denmark and Norway, most of the suppression was probably achieved via voluntary social distancing, as well as basic measures (like restrictions on large gatherings).

It’s true that border controls might have worked in Sweden, but this is a separate issue from whether the country should have locked down. And since Sweden’s epidemic burgeoned earlier than its neighbours’, imposing a total border closure in mid-March probably wouldn’t have made much difference either.

What about the second wave? Here there is slightly less to explain, since Denmark did see a moderate number of deaths – at least going by the official numbers. Norway and Finland, by contrast, managed to keep case and death numbers low throughout the winter.

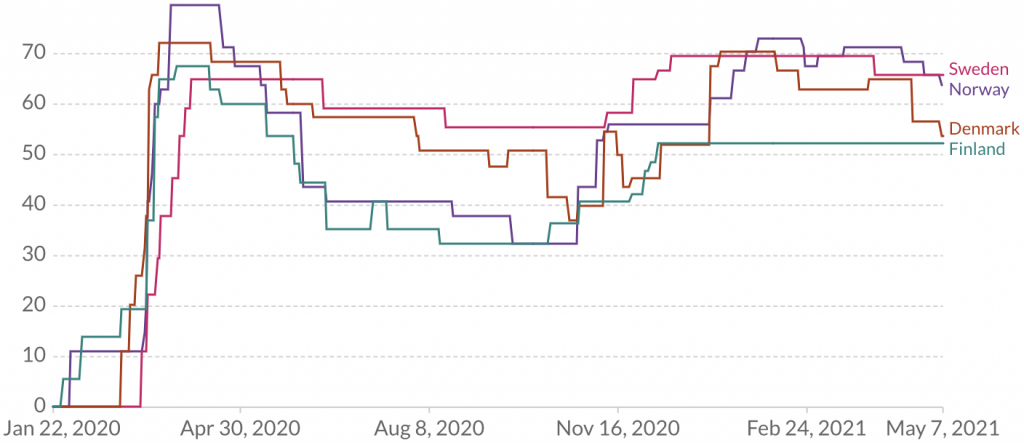

Yet if we look again at the Blavatnik School’s database, it’s very difficult to pin Sweden’s higher death rate on the lack of restrictions. As a matter of fact, Sweden had more restrictions in place than Denmark and Finland for most of the winter. Here’s a graph showing the overall stringency index in each country. (The index is far from perfect, but it gives you a general sense of what happened.)

Once again, none of the Nordics had any days of mandatory stay-at-home orders during the second wave. When it comes to mandatory workplace closures, these were actually introduced earlier in Sweden than in Denmark or Finland. Sweden introduced them on November 24th, whereas Finland waited until November 30th, and Denmark waited until December 9th.

All four Nordics had border screening in place throughout the winter, so restrictions on international travel may have been less decisive than in the first wave. Evidently, Sweden and Denmark’s controls were not able to stop the virus getting a foothold in their respective countries.

What factors do explain Norway and Finland’s success in the second wave is not entirely clear. (They have fewer international ports-of-entry, which may have made border controls easier to enforce.) But there is little evidence their success was due to stricter lockdowns.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I sense this whole coronavirus charade is starting to unravel at an ever quickening pace now. Lockdown’s should never, ever, be used again as a tool to fight virus outbreaks in future. Those who designed and implemented ‘lockdown’ must be held accountable. And the Coronavirus Act 2020 must be repealed.

i find it absolutely incredible that so-called ‘enlightened western societies’ would adopt and implement the very same draconian methods of a communist dictatorship in China?

The only answer I got when I tried to find out who wrote the Coronavius Act was Priti Patel. I do not believe it is all her work. If we can find out who penned, drove and dreamt up the Coronavirus Act, we can get closer to weeding out the diseased evil which is directing this in the UK

Course they shouldn’t, and it’s a disgrace that we’ve been influenced in these measures so much by the CCP

Yes – I agree with this post.

Border Controls BEFORE any significant transmission within the community would be effective.

However, for the UK I reckon we would have needed to impose border controls by the end of January 2020 which pretty much everyone would have regarded as a massive over-reaction.

It’s clear from the deaths (by date) data, that the UK had tens of thousands of cases in February. On the day of lockdown (Mar 23rd 2020), the UK had recorded 938 deaths.

The mean time from initial infection to death is ~23 days (including incubation period of ~5.1 days). Even using Ferguson’s 0.9% IFR, we can only conclude there were at least 100,000 cases by the end of February.

So, in summary, border controls work if you’re lucky enough to impose them before the significant virus transmission in the country.

… and BANG! … we have the implicit acceptance of the central misperception that this virus required exceptional measures – as does the vaccine cult.

Sorry – is you first language not English?

I’ve simply recognised that early border controls would probably have prevented infection. The data strongly suggests this is the case. I never once said that this is what should have been done.

The problem with ‘sceptics’ is their unwillingness to accept the facts – and so they (we) lose credibility. Yeadon was sidelined because he was constantly banging on about herd immunity last summer. Most of us knew he was wrong but he was a main voice and the lockdown advocates ripped him in apart in the autumn and winter,

On another thread, I’ve implicitly acknowledged (in a response to YOU) that the AR is probably lower than I thought it MIGHT be. That’s because more data has come to light.

When the facts change I change my mind – What do you do?

>I’ve simply recognised that early border controls would probably have prevented infection.

delayed (but more likely invested in as you’ll have a large group, better adapted variants and base immunity) rather than prevented.

Border controls might have stayed the onset of infection at best; being an island delayed the arrival of Covid by 2-3 weeks March 2020 compared to mainland Europe but did nothing to stem its development thereafter.

If the border controls were strict enough then prevention is possible. NZ shows this.

New Zealand is one of the most isolated countries on the planet geographically and doesn’t have 10,000 freight vehicles coming in by road every day like the UK. Stop with the ridiculous NZ comparisons.

If virus is not circulating in a country, border controls work.

Is it more difficult to impose border controls in some countries than others. Yes it is.

What’s your point – and whereabouts in Coventry do you live?

Your last sentence sounds like cyber bullying.

I was being friendly.

In theory, yes.

But the key is to keep them shut for good, unless you can get hold of a 100% sterile immunity providing vaccine, which we/they can’t.

Above all, the regular reoccurrence of the virus in all those places despite quasi remaining shut suggests that in practice this will fail and could still lead to just time deferred catastrophes there.

And the most likely explanation for that reoccurrence, failure and also the futility of the vaccines with regard to elimination/zero Covid is that the virus is also present with and transmitted by animals.

Which is one of the major standard criteria ruling out a successful vaccine candidate in general, btw.

… and – as Giesecke pointed out, NZ is now locked into a twilight international existence. that prevents a return to normality.

NZ is sadly yet to face the whirlwind of Covid once it eventually arrives, which it will.

‘Herd Immunity’ is exactly what the vaccination brigade are waving in front of everyone. Except that they want it to be consistent with the revised WHO definition, ie it can only exist through vaccination.

This is of course absolute twaddle. As has repeatedly shown the best immunisation is through the immune system fighting off the disease and getting overall protection rather than just the protein spike.You know, like it has for millenia.

Yeadon was absolutely correct. He was hounded to death ( almost) because his argument was ‘anti-vax’. Nothing more complicated than that.

Yes … the threshold of ‘herd immunity’ is a matter of debate, but the manipulation of the concept to suit big money is a fact.

The HIT in.particular is just a myth in practice, one without any medical evidence.

It’s solely been invented by computer modelers, aka epidimiologists, to justify vaccinating people not at risk of a pathogen or disease, see Profs Gatti&Montanari and the CHD.

HIT is not a myth. It’s common sense. If a large proportion of the population have gained immunity (however they’ve acquired it) then it becomes more difficult for the virus to transmit within the population.

You really have got it wrong. Yeadon has only recently become ‘anti-vax’. I clearly remember him defending the vaccines.

He is anti-lockdown

He is (or was) NOT anti-vax.

His problem was that he was claiming that the UK had herd immunity long before that could have been the case. Sunetra Gupta made similar claims but rowed back on them quite quickly.

Yeadon may or may not have made certain tactical errors but the failure of the anti-lockdown case in general is not to do with a few tactical errors but due to be outspent and outgunned by the pro-lockdown propaganda, on which billions has been spent globally, and backed by almost every major institution on the planet.

Why did Yeadon become anti-vax?

Oh dear, Mayo – you are a touchy little cherub.

My remarks weren’t about you.

They were about the problem of people wittering about irrelevancies to the central point that the danger of Covid at the root of all this was a massively overstated fiction, and that fact should be present in all assessments.

Arguing the toss about what might have reduced a minimal threat is beside the point.

The ARR issue flows from that : it illustrates the minimal level of threat.

That essential fact has strengthed, not changed in a material sense.

and “Yeadon was sidelined because he was constantly banging on about herd immunity last summer.”

…?????

No – he was sidelined (attacked) for voicing uncomfortable truths.

They used his faulty assertions of herd immunity in the summer to silence him. He was his own worst enemy.

But is it not the case our government did everything it could do to prevent natural herd immunity occuring? One could cynically suggest lockdowns are designed so vaccines are the great hope for freedom and Pharma’s bottom line. As for natural immunity see Japan, South Korea and Taiwan with continuing t-cell levels from SARS providing herd immunity.

SARS only infected a minuscule proportion of the population (because unlike Covid it wasn’t transmissible except from people who were already seriously ill) and therefore herd immunity against it couldn’t possibly have existed.

nonsense – cross reactive t/b cell activity in non exposed individuals was confirmed in March 2020

If they were never exposed to SARS how could they have developed immunity to it?

I can’t believe the “East Asians have prior immunity” hypothesis because the only way I could see it plausibly happening is there existed a fifth endemic mild coronavirus which (unlike the other 4) never spread outside East Asia. What’s the chances of that??

I don’t know about the UK, but I’ve done extensive research and original reporting on cases of “early spread” in the United States. Trust me here. This virus was spreading – and spreading widely – in America at least by November 2019.

I’ve identified people in at least four states – Washington, New Jersey, Alabama and south Florida – who had COVID in November or December (they were all sick with all the signature COVID symptoms) – and these diagnoses were all proven by positive antibody tests. Some of these people had several subsequent positive antibody tests. One lady in Alabama, sick in December, has now had three positive antibody tests.

How could someone get this virus in all of these states – all thousands of miles away from one another – if the virus wasn’t “spreading?” And none of these people had been to China.

So any “lockdowns” that would have nipped this virus in the bud in America would have had to commence sometime in November 2019.

Eh? If the disease is already seeded in a country then it is going to spread, irrespective of border controls, which can only limit the degree of further seeding.

And it is simply not possible to put air-tight border controls on a somewhere like the UK.

Hence border controls may delay the onset of peak infection (which may be useful to delay overload of hospitals) but nothing more.

I find NC’s article entirely unconvincing.

Given that none of the other three Nordics had a particularly strict lockdown, their success mainly owes to strict and early border controls.

It’s a cliche now, but Post hoc ergo propter hoc.

Not sure that I agree with or accept that. It is an airborne virus. How far it can travel in the air is unknown but there are examples of folk at sea becoming sick after several weeks away. It would not be unreasonable to assume (as was documented in the original 2019 pandemic preparedness plan) that closing borders would only delay spread by a couple of weeks. France is what, 21 miles away?

Great points here, so I don’t know what the downvotes are about.

Taiwan and Vietnam did indeed close their borders in January 2020, because they both had good reasons to be paranoid about China. Taiwan is actually in a state of war with them, while Vietnam has been invaded by China within living memory.

The success of Australia and New Zealand by contrast is indeed more down to geographic good fortune (I wouldn’t call it “lucky” because there’s nothing random about it). They didn’t close their borders until March (after seeing what was happening in Europe) but that was good enough because up to that point they’d had seasonality on their side, which meant their case numbers were still low.

I am tired of these comparisons, who did what, what was effective.

Comparing deaths alone has so many variables. What the criteria are for counting someone as a covid death, population ages, general health, health care provision etc.

The UK is a much more diverse community than any Scandinavian countries, it is well known we eat the most unhealthy, we have a shambles of a health provision, work long hours, live in cramped accommodation.

I do not think one can say, the fewer deaths the better a country did, one also has to consider how many got seriously ill and the long term implications.

No.

The factors are much more varied, and even if partly true, more questions are begged.

Simplicity is not a good idea when competing with simpletons.

Governments seem to be finally moving back from continued lockdown, but this is no more than a tactical retreat to protect the long term experimental vaxx program. There are still many so called sceptics incapable of realising that lockdown legislation and experimental gene therapy programs are two sides of the same coin – despite the government’s own published MHRA figures showing the danger of dying from a vaxx jab is way out-pacing the dangers of dying from C19, and by some degree.

In the case of school kids, they stand (using the government’s stats) between 50 and 100 times greater chance of being killed by the vaxx than C19 – and that still excludes:

1) the REAL vaxx death figures (as hinted at in the Scottish FOI request and the under reporting of Yellow Card incidents).

2) The serious non-fatal side effects (Strokes, Thrombosis etc) and still unknown side effects (including inter-generational ones that have yet to be understood) as these treatments are still in experimental phase 3 trials, and we are effectively unpaid Guinea Pigs at OUR OWN RISK (as we will not be indemnified for injury or death by Big Pharma).

Nonetheless, the BBC (led by that wonderful Ms Marianna Spring, who couldn’t find any genuine peaceful lockdown protesters despite being in the middle of a protest that numbered hundreds of thousands) and FaceBook are defending vaccines for all they are worth…

This is FAR from over….

Richard and Dave (your BBC link) sound a bit like Amway recruiters targeting vulnerable people!

What on earth is ‘a trainee psychologist’!

It’s possible that the central point of this article is true and arguably useful in order to debunk the usefulness of lockdown but I think the danger is that it just adds fuel to the fire of those who are obsessed with finding some kind of magic formula of measures to “control” or “eliminate” covid. I suppose as an abstract objective it may be worthwhile, but in practice it has led to the utter madness and ruin we have seen, where uncontrolled experiments are carried out at huge human and financial cost on billions of people. I think we have to just stop this nonsense completely, accept that the plans we and other countries had were the right plans and should have been followed, and ponder at length and with calm on how we want to react to some future covid-like virus.

ZOE seems to be ticking back up. It might just be due to a couple of insignificant outbreaks but, if not, government figures tend to follow

No shit.

I’ve said so since a year.

And you can only do that in the first place, if you’re in practice a geographic and economic island or peninsula, which mountaineous Norway and Russia-bordering Finland are, in contrast to Sweden.

And the real key was and is a) keeping them shut for good, see Czech Republic what happens if you don’t, which opens a whole other can of Sentinel Island worms, and b) ditching such and and related zero Covid ideas for good if you missed that initial opportunity, Messrs Johnson, Sturgeon, Sridhar&co.

Disappointing. Why go backwards and pick on one parameter and find a coincidence when there are already papers and articles examining <16? Not sure I’ve heard Giesecke or Tegnell say border controls were the key factor, when there are several other major differences.

Norway eats more vitamin D rich fish (salmon and mackerel) than any country in Europe. And Finland adds vitamin D to basic foods. As for Denmark, I seem to remember a report last year that the Oresund region, straddling Sweden and Denmark, had a similar IFR through the region, despite different rules. Anyone know if this is still the case (or indeed was the case at the time)?

I wonder if Japan’s relatively low death rate is also down to their fish-heavy diet?

yeeey!! totally agree!!

Just few things:

1) There is an AIER article about “stringency index” and is important to keep in mind since it is often used: link;

2) Sweden excess and deficit mortality over 2019-20-21 cancel each other out, just like they do for most Nordic countries, so no real difference;

3) Virus may have become endemic by summer 2020. Dr Clare still keeps a pinned tweet about this (UK example) because it is a reasonable possibility. Check it out: link. Btw, when you look at ONS data over winter 2020/21, a lot of official covid19 deaths are responsible for deaths below 5y average all-cause deaths, meaning a lot of c19 overcounting was happening. And you would expect a lot of excess deaths anyway in winter 2020/21 bcs. of health-destroying lockdowns during 2020.

4) As someone mentioned, there is also real possibility the virus was spread around the world in Q4 of 2020 (causing no excess deaths btw). This is nicely summarized in this article from Dec. 2020 link, and a study in France in Feb 2021. link.

“virus was spread around the world in Q4 of 2020” – Typo: you meant Q4 2019.

This is a major point, and stands to invalidate the article entirely.

The earlier comment that mentioned this is: https://dailysceptic.org/2021/05/11/border-controls-not-lockdowns-explain-the-success-of-denmark-norway-and-finland/#comment-497161

Yes, it was a typo, I meant Q4 of 2019, thanks.

Yes, that was the comment I saw.

If this turns out to be true, it would invalidate almost everything. If it was there for months during the winter 2019/20 and not causing excess deaths, then what happened in spring 2020? Why the sudden spike in excess deaths? The only thing that comes to mind is mass panic and lockdowns.

There’s also idea that is suddenly mutated to become way dangerous by the end of winter 2019/20 but this seems improbable since for the whole year there have been no significant new mutations (as HART mentioned, proclaimed variants are not really that different; media scaremongering with double and triple variants is just another craziness it seems).

There are already about 10 different studies on virus in Q4 in 2019. Unlikely they are all wrong. In any case one would expect governments and WHO putting a lot of effort and resources investigating this (if they really cared about covid19 and science). But almost nothing…

The border controls in Nordic countries are much more complex than shown in the article. In pandemic planning for flu pandemic closing borders might give you a 2 weeks respite except in isolated islands nations, which could be easily blocked off.

The author in the article claims border control was effective in Norway, Denmark and Finland. Against whom? The heavily infected Sweden share enormous land borders with Norway and Finland and enormous ferry/bridge traffic to Denmark. There was free flow of Swedes crossing the borders to their neighbours. Finland, Norway and Denmark international border control did not include the early and heavily infected Sweden.

The article is not very sophisticated. He doesn’t go into interesting demographic details important for spread, with a much larger emigrant community in Sweden. He doesn’t go into an interesting difference in population density especially in Norway and Finland compared to Sweden which is much more urbanized than these two countries.

Not very convincing this was a main factor in the difference of outcome.

Obviously I do understand why the Sweden issue is an important one in terms of proving that lockdowns make no difference. But to continually emphasise this point doesn’t always help I think.

Because what if say lockdowns did work? Would this means that Sweden was “wrong”? No, because it’s still morally incorrect to restrict the ordinary freedoms of healthy people! It’s never proportionate. What China did to its citizens was disgusting and should have been universally condemned not copied.

Or maybe, it just had more to do with Sweden having less of a flu season the prior two years …. Fed up of people looking only at data to justify actions rather than taking it all and analysing in the realm and more comprehensive context

The % of new Swedes more susceptible to the virus is strangely missing

Given the Great Barrington Declaration suggestion about focused shielding of the vulnerable until greater protecting herd immunity is obtained, then the basic principle behind lockdown/shielding is surely accepted by all sensible people. The principle behind lockdown is “effective quarantine” of the vulnerable – while progressing herd immunity elsewhere. (If herd immunity is not being progressed in the meantime then the lockdown is useless). The key phrase is of course “effective quarantine”; for if any lockdown does not impose an “effective quarantine” then it will also be useless.

There are two ways of obtaining an effective quarantine. 1.) At a country or coherent society border, where the self-isolation is not a threat to ongoing life within the quarantined area. and 2.) within a society, such as a laboratory or isolation hospital, but which requires a working society around it to continue to support life within those quarantine areas to enable them to shield properly.

Except for a few countries/islands with the good fortune of geographical isolation e.g. New Zealand, Iceland etc who by good fortune and good management have managed quarantine under method 1.) (but who knows how long they can keep the drawbridge up for) every other country has failed because you cannot quarantine a whole society under method 2.) because some people, essential workers for example, still have to get out to support life within it, and at least one person in every house hold has to get out to go shopping.

The attempt to lockdown whole societies under method 2.) have not produced an “effective quarantine” and never could have, something which is obvious from the beginning just by thinking about it for a few minutes.; and which has of course since be borne out by the empirical data.

To be at least a partially effective quarantine, contacts between people have to be reduced below the level required for the natural transmission ebb and flow of the virus – which is an unknown especially for an airborne virus. As an analogy taking measures to reduce the level of flood from 2ft to 1ft will make little difference to how quickly and how damp everything gets. But to stop the flood all together via quarantine of a whole society is in practice murderous.

An effective quarantine of a whole society within a society is a murderous contradiction in terms.