There follows a guest post by Chris Bullick, CEO of the Pull Agency, a creative branding agency and consultancy, on his recent survey, which found that the public are much less enthusiastic about brands supporting woke causes than the marketers pushing the agendas.

As a marketer who started my career at fast-moving consumer goods giant Procter & Gamble (Ariel, Fairy Liquid, Olay etc.) in the 80s, I have watched the saga around what is called ‘brand purpose’ unfold with weary amazement over the last decade or so. What I saw from the start were brand managers, typically just custodians of brands that others had built (they were standing on their predecessors’ shoulders) bringing their personal worldview, or even their politics to the brands they were advertising. This could never have happened back in the day, it would have been seen as laughably unprofessional. But in some major brand houses it has not only become the norm, but preached as best practice. What on earth has happened?

What is brand purpose? It used to simply mean what a brand was there for. You know: Hellmann’s Mayonnaise (Unilever), put on your salad; Gillette razors (P&G), give you a good shave. But then brand purpose got redefined. Mayonnaise? Fronting the war against food waste. Razors? Fronting the war against ‘toxic masculinity’ (no, don’t ask, women can’t be toxic).

The most notable proponent of brand purpose has been Alan Jope, who became CEO of Unilever in 2019. He has said that brands with ‘purpose’ increase sales twice as fast as those without. Jope capped his first year as CEO with a profit warning that wiped more than £8bn off Unilever’s market cap. Since then its market cap has fallen 25% while P&G, Nestle, and L’Oréal values have all increased around 50%.

Quick definition of ‘brand purpose’ to save time: Picking a woke, unrelated cause and using your brand’s marketing budget to promote it. Case in point: Ben & Jerry’s ice cream (yes you guessed it – Unilever). The causes it supports?

- LGBTQ+ equality

- Black Lives Matter

- Climate justice

- Refugees

- Female body confidence

Okay, you’ve probably got the idea.

Consumer research – ‘Is your brand too woke?’

It was this background of our own unease with the way marketers talked about ‘brand purpose’, the investing world’s attack on it, and marketers generally doubling down and defending the approach which made us think: Would it be possible to get a reading on what consumers think of brand purpose? Mindful of course that we were doubtful that real people – acting as ‘cognitive misers’ – actually thought about it at all.

As a consumer you may not have even noticed ‘brand purpose’ in action. But you might have noticed that ads are no longer funny, for instance. Research shows that over the last 10 years, the number of people who find ads ‘annoying’ has doubled to 50%. So what we wanted to know at the Pull Agency (a brand agency and consultancy) was: What do consumers think of ‘brand purpose’?

We decided to find out. But we instinctively knew that some of our marketing colleagues would be uneasy about us asking. So we ran the survey we had in mind past a few marketers.

“We advise strongly against it.”

“It could be seen as divisive – we’re not sure it’s a good idea.”

“It isn’t inclusive enough.” (No, we never understood this comment.)

The plan was to create a survey of what a fully representative panel of over 2,000 U.K. consumers thought about brands supporting ‘progressive’ causes. The survey itself didn’t actually use the W-word, and we had gone to great lengths to create a balanced range of answers to the questions. However, our fellow marketers thought we were on very dangerous ground which we were advised to stay off.

We went ahead with the consumer survey – and held our breath.

“Loved it.”

“Very good survey.”

“This has educational purpose.”

“It’s got me thinking.”

“Interesting topic and very relevant…”

“I am pleased to see this survey subject is being considered.”

Of all the agency and client research we have done, this research into consumer’s attitudes to brands that take a woke stance got the most free text comments: 20% of participants commented, and 25% of those comments were overtly positive feedback about the survey itself. Something strange was going on here. Marketers didn’t want us to ask the question, consumers said they were very happy we did.

In a sense I could stop there. This revealed perfectly the issue about brands and social purpose. As a guest panellist at our survey report launch event pointed out: marketers are WEIRD (from a Western, educated, industrial, rich and democratic elite) and consumers are not.

So in this article I will address, firstly, what did we find out about what consumers make of what marketers refer to as ‘brand purpose’? Secondly, why are today’s brand managers and their agencies playing with ‘purpose’ in this way?

Experienced researchers will warn you what to expect conducting surveys in a world of social media censoring, cancelling and rampant virtue signalling. More than ever before, consumers want to give the socially ‘correct’ answer, even in the anonymity of an online survey. Toby Young has written about this ‘pro-social bias’.

Andrew Tenzer (researcher for Reach Solutions, the U.K.’s largest news publisher) related at our survey launch event how he regularly asks for a show of hands for the question: “Given the choice, would you prefer to buy from sustainable suppliers?” Almost everyone puts their hands up. “How many have bought something from Amazon in the last month?” Almost everyone puts their hands up. Researchers face a massive challenge in that there is a huge (and I believe increasing) gap between what people say and what they do in respect to all the fashionable issues in particular.

Our consumer research into brand purpose – what did we learn?

68% of consumers are uneasy or unsure about brands supporting woke causes. This should give marketers pause for thought. But on the other hand, and I have to say I was shocked it was this high – it meant that 32% of respondents thought that brands should support as many of our offered list of causes as possible: climate change, BLM, LGBTQ+, equality, diversity and inclusion and female body confidence. At the other extreme, 8% said that they would actively avoid brands that support those causes. Of course, the question that is harder to answer is whether the 32% would go out of their way to purchase brands because of their support for social, woke or political causes. There is no evidence we know that suggests they would. Academic research suggests that the 8% are more likely to act on their sentiment than the 32%.

There are strong generational differences in attitude among sexes and generations. Women were nearly twice as much in favour of brands supporting social causes than men, and Gen Z were three times more in favour of it than Boomers. But again, we don’t know to what extent this translates to buying behaviour. It’s worth bearing in mind that many researchers like to suggest that younger generations have both a better moral framework than older people and are more likely to buy sustainable brands, without any evidence for either in terms of actual behaviour. However, you have to be careful about muddling generational effects with cohort effects. Young people have always been idealistic and cause-driven, but young people grow up.

Consumers’ trust in brands’ involvement with social causes is shaky. While on the one hand quite a high proportion of consumers say that they want brands to get involved with social (or woke) causes, 58% think that a lot of that involvement is insincere – woke-washing or green-washing. Demonstrating that perhaps it is easier to make enemies of consumers than friends through promoting social causes, 15% of consumers say they will avoid brands that they think are indulging in woke- or green- washing.

Consumers have had plenty of opportunity to say that they endorse brands supporting social causes in research over recent years, but to our knowledge this has never been tested against alternatives. Well, we did. Pro-social bias means that there is pressure on consumers to say they support fashionable causes. But what if they are given an alternative?

Then the picture changes quite rapidly. Can you imagine if Starbucks or Amazon or Ben & Jerry’s put these alternatives to their customers, what their answer might be?

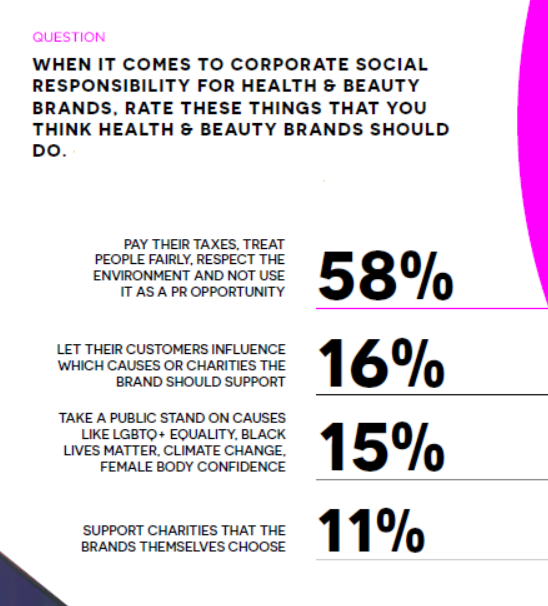

58% of consumers would prefer that brands simply pay their taxes, treat people fairly and respect the environment – almost four times more than want brands to support woke causes.

We know marketers like supporting woke causes with ‘their’ brands; consumers appear far less enthusiastic.

60% of people don’t feel well represented in health & beauty ads; this percentage rises for white people and older men. 29% of people of BAME ethnicity described themselves as well-represented compared to only 19% of non-BAME. Contrary to a commonly expressed view within the marketing community that the industry needs to ‘do a lot more’ about diversity and inclusion, it looks as though it has in fact done enough (but perhaps clumsily) when it comes to representing ethnicity. Research in 2020 by the Creative Diversity Network based on 30,000 TV productions found that both ethnic and LBTQ+ minorities were represented at twice the population rate, and it was older people and the disabled that were the most under-represented.

Our research mirrored this finding. The unthinking addition of ethnic, and in particular mixed-race couples, is seen by consumers as an ‘easy win’ for lazy advertisers and contributing to the impression that advertising has ‘gone woke’. It was clear from our research and comments we received that people are simply looking for realistic representation of the reality of U.K. population diversity. Advertisers need to be more imaginative in dealing with this. The largest group in our research by far – 43% – chose the option that brands should simply “reflect the real users of the brand”.

The concept of ‘body positivity’ hasn’t been extended to men – 64% of men don’t feel personally well-represented in ads. It seems that the gender equality that so many brands want to be seen to support doesn’t work the other way round. The current practice of using imperfect female models in ads, according to many of our research participants, doesn’t yet seem to have been extended to men.

So what’s going on? From our findings you can deduce:

- Consumers want to ask questions about whether brands are too woke – marketers would rather no one did.

- Consumers are uneasy about brand support of woke causes – marketers aren’t.

- Consumers would prefer companies to pay their taxes, treat people fairly and respect the environment – marketers would prefer to tell you about their ‘brand purpose’.

- BAME consumers feel well represented, men and non-BAME consumers don’t. Marketers think that their industry ‘hasn’t done enough about diversity’.

- Consumers used to find ads entertaining. Marketers want to tell consumers how they should think.

Would it be fair to say that marketers are out of touch with the people they are marketing to? Yes. So let’s look at more of the evidence. Andrew Tenzer from Reach plc told our report launch event that marketers are WEIRD – that is from a Western, educated, industrial, rich and democratic elite. The idea of WEIRD was popularised by the leading social psychologist Jonathan Haidt in his book The Righteous Mind. Andrew expands this idea in his paper The Empathy Delusion, showing that marketers tend to think they have advanced levels of empathy and a superior moral framework. Unfortunately, research has disproved the former and of course no research supports the latter.

In addition, research shows that modern marketers self-identify to the Left politically of the modern mainstream, are (for instance) less proud of their country’s history and more likely to believe that women and men have identical roles in society. Translated into the language of the modern mainstream – marketers are woke, the mainstream isn’t. As a result, brand purpose “is highly seductive to our industry on a personal level”, Andrew explains.

My beef with all this is that this brand purpose charade is bad marketing and undermines the profession and the concept of effectiveness in marketing. Even back in my days at P&G, the company would occasionally be berated as the U.K.’s largest advertiser (nowadays that of course is the Government) for such ‘profligacy’. The company defended its large advertising budgets with the logic that good advertising – especially for good brands – was the most efficient way of matching buyers with goods and services. It created efficiencies in the economy. Modern marketers seem uninterested in such commercial logic. They see themselves as on a much higher moral mission. The result is ‘brand purpose’, which in reality is therefore just virtue signalling and an indulgence that they feel they deserve – it’s all about them. With the likes of Unilever’s Alan Jope egging them on, no wonder they feel unconstrained by thoughts about whether it actually builds their brands or sells their product.

So next time you see a brand clambering onto the latest woke cause, spare a thought for the poor marketers and their agencies. They just can’t help themselves, the poor dears.

You can download the full research report here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I can see why this survey was conducted; because people in all manner of businesses like to get direct feed back from their customers. But I would have thought the clearest signal of what consumers really think, is the effect on the bottom line. And it appears that “Go woke, get broke” has been a decidedly accurate description. This survey merely confirms it.

Aye trendy is as trendy does; but a poond is a poond.

This has been going on for so many years now. I will not buy anything that has the slightest whiff of woke about it. The same goes for clothing catalogues with a high proportion of “foreigners”in there that look totally ridiculous in English clothing with their huge shoulders. Also anything sustainable gets cancelled. This is so obviously subliminal advertising in order to change our way of thinking.

Being concerned about brands serves as a proxy for IQ.

I have found that every time I hear of a woke brand doing something outrageous and I want to boycott them … I find I never buy them. However Hellman’s was mentioned, so I’m going to check next time I buy and put it back if it’s Hellmans

It would appear that Gillette is currently managed by f*wits. Who in turn employ ad agencies staffed by f*wits. And then approve the resulting adverts.

Which are then lampooned brilliantly by Gervais.

If nothing else, I’m grateful to Gillette for that Gervais tweet.

Thanks, Gillette.

“the public are much less enthusiastic about brands supporting woke causes than the marketers pushing the agendas”

Of course that’s the case. If everyone already supported the woke causes, those pushing the agendas wouldn’t need to bother. This is about changing public opinion, not reflecting it. It seems to me that advertisers used to try to tap into markets based on what they thought people were really thinking, now it’s just a cover for propaganda. I don’t know if it’s that those at the top are taking orders from someone or whether those that go into advertising are now all spontaneously trying to change the world “for the better”.

Given a choice between two brands, one extreme woke and one just woke, I’ll go without.

You are correct..this is more ‘giving the public what they never asked for..needed or wanted’….. we, the ordinary public, are totally at war aren’t we, with everybody it’s seems, who want to ‘green’ us ‘woke us’ or ‘medicate us’ …out of existence..

I think a lot of them are probably frustrated politicians or do-gooders or “artists” or whatever who are desperate to signal their virtue and “make a difference” and bugger the paying customer.

Nope. For the most part, advertisers have to be open to working on every kind of brand. A typical creative is going to work on many hundreds of brands over their career. Asking to stick to brands you personally agree with is absolutely not an option.

They’re more likely to enjoy the challenge of taking on something different. For example, advertising for a political party they don’t vote for.

Judging from the piece, there’s clearly room for an “ethical” advertising company who don’t do woke, it sounds like a no brainer.

There are hundreds of ad agencies – the choice is out there.

..absolutely missing the point I think….Julian’s point stands..this isn’t about advertising your product, it’s about some virtue signalling…in the same way the BBC has lost vast audience numbers by giving us ‘woke re-written’ history none of us are interested in…it might be great fun to write, and occasionally amusing, but when it’s all the time it’s about more than that..as he says it’s forcing an agenda on to you that the vast majority don’t want.

Julian is wrong for a number of reasons. Firstly, ads aren’t produced by one person, but by many people in radically different roles with radically different interests. Most brand managers don’t give a stuff how creative or interesting the ad is, they just want it to maximise their product.

Secondly, everybody’s motives are dominated by fear. Fear of losing their job. Failing to sell stuff is one way to lose your job.

That’s their agenda. Keeping their jobs.

…but again he’s right, because what you are saying now is that fear makes them tow the line…and still they promote the agenda, or at least don’t question it…?

Fear of getting fired, not fear of some agenda.

Top ad agency creatives are always looking to challenge assumptions and do something different. For them, doing what you’re told would itself be a route to failure.

In any case, there’s no evidence that anyone in ad agencies is being directed by some mysterious government force or whatever.

None of which would even begin to explain why Gillette thought that insulting its target audience would be a good idea.

Perhaps they hoped the wives and girlfriends would like it and persuade their ‘toxic’ significant others to change?

I haven’t personally noticed the ad in question. But whatever your intentions, things don’t always come out the way you meant. There are a thousand compromises involved in marketing, as in most areas of business. Sometimes, those compromises are fatal to the intention

Then they’re failing. Their customers don’t agree with them and dont don’t like their adverts to such an extent that boycotts have occurred just because of offending ads, not the products, eg, Gillette.

That would be quite the challenge, to think up positive things about a party for which you’d never vote. I suppose at least you’d know whether the ad worked, next time you put down your ‘X’.

Do you mean that last phrase literally or as an expletive? The way things are, I suspect the former is more “appropriate”

We’ve also got an actual war going on at the minute, which we didn’t ask for either, on which the PM is spaffing £Billions

But that is to establish gay rights in Russia. An important milestone they seem to be rejecting.

‘… at the top are taking orders from someone…’

Yes. We do have a move to global governance. Nothing is coincidental now, whatever ‘cause’ is universal – same rhetoric, same timing, same policies in all Western Countries.

There seem to be quite a few members here who worked m marketing. None of them are saying they were directed…

None of them is, not are.

But, to be fair, all of them aren’t.

Old fashioned view which no longer holds in usage and not really in pure grammar either. ‘None’ can be singular or plural. It can mean ‘not any of’ as well as ‘not one of’.

Most aspects of grammar ‘no longer hold in usage’.

Mankind now needs only one all-purpose adjective – ‘Awesome!’

But they are directed. They have to work to the brief they are given.

Yes, but it’s a brief developed between the agency and the client, and no one else.

Liberal hivemind. They all think alike, and want us to follow suit.

We can think for ourselves, so won’t.

L’Oréal get cited earlier in this piece for their profits increasing in contrast to Unilever. The point being that woke goes broke. But hold on for a second: l’Oreal have embraced the brand purpose ethic, and gone all in. I happen to know, as I happen to have access to some of their internal materials. Don’t ask how. They are obsessed with gender identity and related topics and are turning their massive corporation into a shrine to woke insanity.

Indeed. I have similar access to the corporate internal output of a global firm operating in a business to business sector, so not even dumb consumers to worry about. They are the same – full-on woke. Why?

Dunno. I work for a bank and it is like that. I think they (they = c suite) think it is necessary to attract younger (under 30) employees. I must admit the 20-somethings do think I am a weird anachronistic dinosaur, with my children and so on (imagine!), so maybe they have a point. Totally alien.

People use L’Oréal products because they want to project an image (aka look good), even more so than the run of the mill alternatives. Perhaps those people view wokery in the same way, hence the woke marketing is a positive for them?

https://www.beautypackaging.com/contents/view_online-exclusives/2022-05-24/loreal-ceo-speaks-about-responsible-consumption-at-world-economic-forum

LOL!!…. I was just reading this. L’Oreal CEO….….Nicolas Hieronimus discusses sustainability—and the solution L’Oreal is focusing on to help save the planet is refillable packaging.

That would definitely make me stride into Boots, shove all the other products off the shelf and pick up a pack of L’Oreal something or other – the refillable packaging.

I have nothing against refillable packaging – if companies can do it then it is a sensible sustainable idea. But would it be the one thing that swings it for me? Not so much.

In the early 80’s I worked at the ad agency, which, among clients like Vauxhall, CoI, Goodyear, Philips, also had L’Oreal. This appeared in the agency accounting systems as Golden Ltd.

It was pretty straightforward stuff. Advertise the product and its USP(s), in such a way that it sold as much as possible. The Philips stuff, some of which featured Daniel Massey, was quite novel for the time, and there was an argument around the business and the industry, as to whether Advertising (in the film/commercials sense) should be, or aspire to be, Art.

As for what is now “woke”, the clients would have choked over their lunch at The Ivy or dinner at Langan’s, if the topic, or something like it, had been aired.

They had a model who was/is a transgender racist who hates white people, who they sacked then reappointed.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-41127404

My understanding is that L’Oreal has seen higher growth than Unilever because Unilever operates in lower growth segments (like food) whereas L’Oreal sells high science skin care, which the females among you may have noticed, has had a bit of a ‘moment’ in the past few years, and is one of the fastest growing consumer categories, alongside vitamins and supplements. Especially in Asia, where L’Oreal have a significant presence.

Please just publish the list of woke brands so I an ensure I never buy them again.

I abandoned Lush after stumbling across the political idiocy on the website, and then after the Gillette nonsense started keeping a checklist of companies to avoid, but it rapidly expanded during the Summer of BLM to include more or less every single company. Some companies and organisations seem to big to be much affected by consumer opinion.

Speaking of the Marxist blm, should we not boycott all football and now I saw Rugby League Cup final yesterday genuflecting to that new God.

You should abandon Lush simply because their products are (1) ludicrously overpriced and (2) stink to high heaven

Contains lot of chemicals – all absorbed by the body

It’s a really long list, it’s a challenge to not give them any money but really rewarding!

I am avoiding any company that supports woke causes. Cancelled my Peoples Lottery s/o as they fund some ECO nutters .Its in the small print on their site but not obvious at all.

I only found out as the ECO nutters were trying to sue the Govt and this was highlighted on Paul Homewoods excellent Enviro Lunacy site Not a lot of people know that.

For food I shop at Aldi so not many woke brands but if they start using mixed race couple in their ads like Lidl I am stuffed for any real choice..

Hadn’t noticed the Lidl inclusivity, but then, I walk into a shop, buy stuff and walk out again. If they remain good value, I’ll overlook the non-representative advertising. My local Lidl seems to be staffed entirely by Eastern Europeans, yet they don’t have any sauerkraut (or Kapusta Kiszona) on sale. Missing a trick there, I think.

I thought Lidl went more for all-black families rather than mixed race now.

Most of them.

and if the brands themselves are not, their adverts generally will be.

For me is easy. Pub placards on the streets must show brown or asian people. Or people no one can say if IT IS a male or a female. The only (normal) white woman I saw was in a Zeiss advert.

This survey merely confirms what we already knew: the metropolitan, university-conditioned, labour-voting, middle-classes (although few admit it, they prefer to see themselves as an oppressed underclass) are drenched in sanctimony. They see it as their holy mission to bring the light of their moral superiority to the dirty, knuckle-dragging proles.

It stretches across all fields, marketing is simply a highly visible manifestation. For a clearer view of the city/country delineation, just look at the political map of Lab vs Con results – not that small-c conservatives have any real representation in mainstream politics.

On another level, it shouldn’t come as any surprise that those of us who live surrounded by the beauty of this country’s rural environment should wish to preserve something of our nation, its culture, traditions and character, while those surrounded by the grime, violence and 3rd world enrichment of our fallen cities feel a strong desire to conjure up a new utopian reality.

Very good appraisal. Nowadays, marketing is the Kings’ clothes.

It’s been that way since the late 1960s

I have noticed that the amount of mixed race families in adverts is not in proportion with real life.

I haven’t noticed any mixed race families … since I stopped watching all adverts.

Back when I still watched live TV, I would record the programmes in which I was interested. Those from the BBC normally had at least 2 minutes-worth of BS at the start, whereas C4 and ITV had ad breaks of almost exactly 4 minutes.

Since my satellite recorder had a handy button that FF-ed in 2-minute intervals, I could avoid the BBC BS and the commercial channel ads with only one or two button presses.

Bliss!

Quite. I never knew that such families, with a resident doting black father, were probably the majority. How educational advertising is!

I think I mentioned this before, I was at a motorbike festival a few weekends ago and was astounded to see out of 10s of thousands of people maybe 8 black people all weekend, genuinely had to give my head a shake, clearly I spend too much time on the internet.

Motorbikes are racist, obvs.

Yet, most of them seem to be black.

Did this take place in the countryside? Because we all know that the countryside is racist (apparently).

only in advert land.

I may be wrong but don’t advertisers have a legal obligation to produce ads that tick the diversity box?

Ofcom have been active in making sure that output conforms to the Equalities Act 2008. For advert makers, the easiest thing is to fill their adverts with diversity, usually a mixed race couple, (black man, white woman, some visa versa) then they can’t be accused of not ‘being diverse’. However with diverse actors now being more than 50% of the output, in a land where 83% are white, it is reasonable to ask where the equality is for white folks.? I was of the opinion that there is only one ‘equality’, maybe I’m wrong.

Many brands only produce one tv ad a year, with just a couple of lead characters. If you’re not going to be permanently all white, you’re bound to end up over-representing a minority.

The Equality Act 2010 s4 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15 lists 9 ‘protected characteristics and details discrimination involving those characteristics.

age;

disability;

gender reassignment;

marriage and civil partnership;

pregnancy and maternity;

race;

religion or belief;

sex;

sexual orientation.

There is no requirement to misrepresent minorities to avoid discrimination and I’d be interested to know of case law where it has been successfully held that advertisers must do so despite minorities or even large sections of the population not fitting an advertiser’s target audience.

Reminded that I was with friends in a small N E Wales town when a mixed race couple passed by with a couple of ‘kids of colour’. Normally would not have noticed until amused friend said quietly ” was that real life imitating adverts ?”.

Then, why don’t they feature any fat white blokes?

No they don’t

Very much so in Somerset, where a PoC is a rare event, so watching adverts which feature ONLY PoCs is beyond bizarre. We resolutely monocultural down here (and of course, culture, by definition IS mono. Multiculti is another way of saying – we have no common culture,

Staying with friends in Wiltshire some 5/6 years ago I noticed that all the presenters on Look West were ethnic minority.

Since watching current advertising showing aspirational lifestyles, I want to be black and have a flying wheel chair.

and be fat

Being fat is interesting. Looking round (pun intended), it is clear that very many people are at least a stone heavier than Government / NHS suggests they should. The MSM bangs on about an ‘obesity epidemic’.

OK, try to buy a pair of trousers bigger than size 42.

Good luck.

I got mine from M&S and then decided not to repeat the experience.

The obesity epidemic is somewhat over-represented in the NHS

Quite – at our local big hospital, the RUH in Bath, you have to dive into broom cupboards to evade many of the nurses. Or be crushed.

That sort of behaviour got Boris Becker into trouble.

Explains why a relative’s Caesarian happened 8 hours later than scheduled there – the nurse find it difficult to move!

The nurses?

Considering they’re a) always run off their feet and don’t have time to eat properly, and b) too poor to afford to eat properly, why are so many of them so fat? What are they eating? The patients?

I have already achieved that with the help of my Mum and her three meals a day and choice of puds. She established my lifestyle 70 years ago.

It seems to me that there must be a group of idiots in society who like to pay more for “brands” and particularly woke ones. However, now woke has caused the cost of living crisis through green fuel energy price rises on top of covid insanity inflation price rises, the first thing people will be cutting out from their shopping are the expensive woke brands.

I see a lot of woke = expensive = low-value brands going broke.

Quite recently, a Tesla concession opened up near me, and now there’s a rash of ‘cheaper’ Teslas on the roads. Only yesterday, I watched a YT vid of burning Teslas (and Hyundai and Kia EVs, for the sake of balance) and determined never to park next to one.

Reading the comments, a simple phrase comes to mind:

classic example. Robinsons squash. The label on the front of the bottle does not say in big letters what the product is, no the big letters inform the consumer they have bought a disposable bottle, in small letters at the bottom, it says Lemon.

So presumably the selling point for the brand owner is a botttle which is disposable, not the contents inside.

Likewise the use by what seems to be everyone selling something of the word “sustainability”. Sustainablitiy of what? profit, sales, employment, the garbage used to persuade us to buy the stuff?

frankly any company that focuses more on virtue signalling, which after all is what this is about, is a company that has forgotten what its purpose is, whcih for me is the creation of a product that people want to buy because its a well produced thing which has in itself good properties. That is what many CEO’s have forgotten, most of these people did not invent the product, its not their baby as it were consequently they have no love or belief in it, hence they use the “latest thing” in terms of woke fashion to try and sell it. For me its a turn off, if they aren’t proud of their product why would I want to buy it.

Golly! You buy Robinson’s?

🤣🤣

Never forgot: all this mind poverty is for money.

The Heineken advert on TV during the football last night was pure woke shite

Then again i would never drink that crap anyway

I hardly ever watch TV/adverts, last night saw that advert and though, wtf are all these women doing in a football and beer advert?! Then saw the tagline…

Although, as a pure money grabbing idea it’s fair enough, advertise to the 50% demographic you haven’t already got as customers. Still, I’d rather they did this by demonstrating the smooth taste, or amazing price etc. It was drifting awfully close to “don’t let the men stop you from enjoying sport and alcohol”. If I wasn’t on constant woke alert it could have slipped me by, not the most egregious example (hello Gillette) I’ve seen spoken about but pretty bad.

‘Probably the best horse urine in the World’.

I think I’m sexist.

Quick simplified version of what seems to be the issue here, women mostly teach (and to a degree I suspect work in advertising). Women fall for these causes more than men. Women teach everyone to think like they do. The problems started when governments started to seek the votes of women and advertisers the second income, birth control became an option breaking apart the family and the welfare state took over the role of father/provider. Fast forward 50 years or whatever and look at society now. It’ll only get so much more worse before there is a massive snap back to the right. Apologies to any traditional/conservative women.

Everything is cyclical 🤠

I agree. You should hear my mother (81 years old) on the subject. She has no time for most modern women.

A weird conclusion not based on evidence…’I suspect’!

Spare a thought folks. This woke brand can’t get a roof over her head

Ukraine: Vegan refugee struggling to find a home – BBC News

She ‘struggled through Europe to reach the UK’, which is a pity as she might have bypassed many vegan hosts along the way

One wonders what she ate during her journey. Roadkill? (Ethically-sourced and humanely despatched.)

There’s no vegans in foxholes.

Just another cult for people who cannot find meaning 🤠

So she DID find a host family but after confronting the family about their lifestyle choices she was told to sling her hook. Can’t fault them

Just read that – silly c**t.

WTF are we playing at inviting woke, ungrateful retards in to this country?

I’ve got a response to her whingeing:

“Ticket back.”

“Oksana Kopanitsyna said being in the same room as someone eating or preparing meat was like “someone was cutting a child in front of you”.”

You mean…there aren’t that many vegans around?? Well, you could knock me down with a vegan carrot…or preferably a fillet steak.

We did our weekly grocery shop at Sainsbury for 20 years. Say £1000/month = £12k pa, £240k total.

Eventually got sick of its relentless LGBT campaigning so complained to its CEO.

After being fobbed off patronisingly, took up our trolley and walked.

Did the same with John Lewis too after its trans kids push.

Do the maths, vote with your feet.

Make the woke broke.

A grand a month? What were you living on?

I’ll second this motion. A thousand quid a month?

Was it special steaks from endangered species? Dolphin burgers?

🧐

Teenage boys??

My friend had two who could eat their way through the contents of a heaped trolley Saturday shop by Wednesday….

When they left home food miraculously stayed in the fridge until the planned meal was cooked & she more than halved the food shop bill!

Putting 3 offspring through uni at the same time somewhat counterbalanced the savings!

Haha! Teenagers, dogs, cats …

And dolphin burgers are cheaper at Aldi.

Haven’t set foot in my local or any other sainsbury since they had five goons enforcing masks on the door at the same time as celebrating ‘black history month’, i’d never seen a ‘white history month’ being celebrated, let’s face it, it would have to be ‘white history four months’ if we’re going to celebrate proportionately.

Your numbers are off. It would be white history year, with about three seconds of black history. Literally jazz music, rap music and athletics, all practiced in white countries where the infrastructure to support all three was built by whites.

except the same uber rich class built both…

Great!

I stopped shopping at Waitrose after 16 years due to their over enthusiastic policing of masks at the door during lockdowns. Never been back!

Ditto, I boycotted them after their message about if you don’t like our push for diversity then shop elsewhere. So I did, and I spend around £400 per week on food and drink

Sainsburys is a very bad offender on all counts of everything that makes Great Shitain the Communist craphole it now is. Their ceilings are lined with a ridiculous amount of wifi routers and theyve installed those hideous, Orwellian, New Normal, radiation emitting surveillance screens at the self service. You can literally feel the electromagnetic radiation in their stores. Then there is the issue of the knuckledragger aggro moron security Nazis they employ who are absolutely horrible in the way they go about their jobs. I hope they go down the toilet and end up being flushed into the sewers where they belong. I pray for these companies to get their comeuppance and pay for their crimes. Its time to not only boycott these traitorous companies, but also to shout out loud about the anti human anti freedom agenda they serve. I despise them. I had been a customer of theirs since day dot, as my mother used to shop there, but now I couldnt have a lower opinion of them. Their food went downhill some time ago and now their stores are all DYSTOPIAN HELLHOLES. F*** Sainsburys

Communist? I thought they were largely owned by Qatar.

Great article. Plenty to be concerned about within but little focus on the scale of gov marketing spend. Some of the brands need to spend to get their share of your wallet but gov spending is about control in different forms. Deeply worrying that one.

Thank you for an interesting and enjoyable article. The heyday of advertising is sadly long gone and the creativity and wit of campaigns like those for Smirnoff vodka and Hamlet cigars won’t be seen again.

I’d say those energies are now directed towards memes. Some of them are quite thoughtful and funny.

It is noteworthy the hard left don’t meme. Their ravings require a carefully constructed false reality to work. The successful memes are instantly graspable. Example below.

Brilliant!

Indeed. I feel guilty for not having worn one now.

Smack Talk: Gillette The Best Men Can Be

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zzpx9VX9hoI

I think that people who wear brands are inadequates. If they fall for the corporate whine and sludge, there is no hope for them.

We don’t need no stinking badges!

Back when ‘designer jeans’ became a thing, I had to admire the gall that asked people to pay more to wear clothing that advertised the manufacturer. Didn’t stop it working, though.

Ditched Gillette the moment I saw that Ad and haven’t touched them since.

Whitey being erased from TV Ads is quite blatant. I rarely watch TV and ffwd Ads when I can but it’s in your face 24/7 now lol.

This is assuming advertising is important to the human race.

It’s not, it’s important to those wanting to sell something.

But is it important to me as a consumer? Yes it is. I need to understand where to go to get stuff. For example, I’m an overweight 65 year old. Do I go to Top Shop for my clothing? No, I have more sense and dignity, I seek out stores that suit my age and physical stature. Some have Adonis’ as models, some have fat blokes as models. I really don’t care, providing the clothes are the right size and quality for my purposes.

Do I want to see blubberised 65 year old geriatrics pirouetting across my TV screen making me feel inclusive?

No, it’s unattractive and off putting. It’s also pointless, just tell me the nice clothes worn by the models are available in my size, I’ll figure out the rest. Brands to me represent quality of product i.e. will it be around after a years worth of washing. I have several Slazenger polo shirts that are 15 – 20 years old, worn and washed daily (rotationally, so each washed perhaps twice a week). Other than being slightly faded, they are in perfect nick.

Do I care if a skin product is advertised by someone with black, white or yellow skin? No, because it’s skin, it doesn’t matter what colour it is, nor what size you are, nor if you’re LGBTQ+ or in a wheelchair.

Does it matter to me if my car is advertised 100% of the time with black families as the models? If I lived in Nigeria, almost certainly not.

Does it matter that almost every advert for breakfast cereal includes mixed race couples with mixed race kids? Not really, it’s just a bit daft that this is presented as a typical British family, and it’s clearly not. Consumers have thinking brains, we’re not all automatons, and slaves to diversity and inclusion when we know full well that a ‘typical’ British family is more usually white. Sorry, but that’s just the way it is.

To fulfil diversity and inclusion quota’s, should it be necessary that LGBTQ+ clothing manufacturers (is there such a thing?) include straight white males in their advertising, proportionate to the number of them in the country, and for the moment leaving out skin colour an mobility issues?

Things will change as the ‘get woke, go broke’ mantra begins to affect profits.

The Long March Through The Institutions is a slogan coined by Communist student activist Rudi Dutschke around 1967 to describe his strategy for establishing the conditions for revolution: subverting society by infiltrating institutions such as the professions.

Well done (sarcasm). The Institutions are now churning out graduates who have a Woke view of the world and these people now have jobs and believe their subversive goals. So we have charities that have become ‘wokly’ politicised, corroded journalism, and distracted politicians. It’s only another step to media types in advertising believing that their world view is just and that others will buy into the dreams they sell.

Perhaps reality will turn out to be a harsh mistress, but only after enough Woke people run out of excuses for failure.

Reality is always harsh. Just ask the older Russians. The current success of woke is probably a consequence of placemen and the long march through the institutions. But that won’t help them. Their views are fantasy.

A great example is Klaus Schwab. He is wealthy enough to have the free time to indulge his world view. He gets airtime. He seems important. But is he succeeding?

Most of this stuff challenges reality. It can’t work. Mixed race couples are rare, although have always existed. Most prefer their own. The most sexually conservative group in the US are black women; 98% want a black husband.

What we are seeing is fools with the connections and money to advertise their private obsessions. But behaviour isn’t really changing.

Sadly something that was ignored. In the same way the WEF has been ignored for too long.

Yes. We have a government that (in name only) is “Conservative” and a Civil Service that is anything but, and intent on imposing their world view on one and all. Long ago they forgot who pays them and for what we pay them.

I wonder if any of this will matter later in the year when many people and families won’t be able to afford to put food on the table or pay the leccy bill…

Unless they are on benefits.

Have you ever tried living on benefits? I haddn’t until lockdown F’d my business, I got <£70 per week, didn’t even cover the mortgage.

‘roll all you debts into one easy to pay really massive debt’

Some valid points. But the fact is that cause related marketing has been very effective for some brands. For example Dove was one of the first to start using ‘ordinary’ models, including older women in overt ‘beauty’ roles – a real breakthrough and successful for the brand. But of course, some brands push it too hard. The cause has to be credible for the brand to take.

Discovering that people prioritise brands that pay their staff and taxes over taking a cause is so obvious it wasn’t worth asking. Taxes and pay are themselves part of the moral obligations of a brand. It’s part of the same package.

I would suggest that the over-representation of some groups (BAME) is not necessarily because the advertisers are themselves woke, but because marketers are currently more afraid of a damaging negative than a slightly weaker positive. It is a general society behaviour to be more ‘woke’ in appearance than we are in reality. Why wouldn’t brands reflect this?

On the whole, most marketers tend to reflect society more than lead it.

“On the whole, most marketers tend to reflect society more than lead it.” Sorry but how is aggressively pursuing a policy of eliminating straight white males from advertising reflecting society?

To say that straight white males have been eliminated from advertising is a massive overstatement – rather, it’s a shift in proportion. And in the vast majority of ads we have no clue what anyone’s sexuality is.

There has been a marked increase of BAME models over the last decade, that’s for sure.

Older men and women of any sex, any colour have always been less represented except for products designed for older age groups (eg retirement services).

Many ads only have one or two central characters which presents a problem. Most groups are by necessity going to get left out.

“Older men and women of any sex”. What?

Sorry, should have said ‘older people’.

My point is that older people in general have been under-represented compared to their number in the population. Not just white older people.

Older people buy less stuff

plus, even in those ads for walk-in baths, the models are usually lithe and attractive

Yes, it’s like the ads for tooth whitening toothpaste that use models who already have very white teeth, or denture fixative that shows people eating apples with their own teeth.

Depends what it is – but older customers certainly don’t live as long.

From what I can see, this forum is heavily skewed towards the very end that they’re complaining about missing – ie white, middle-aged men with socially conservative views.

I wouldn’t know, being young and attractive myself, but I suspect that once you have hooked an older customer, you have landed someone who is going to be a more reliable and loyal consumer than the fashion-driven youth.

Older people have more money.

Some do. Many don’t.

I can immediately think of two ad’s on TV today that show two women kissing in public.

I have never seen two women kissing (in a sexual manner) in public, in my whole life.

I can think of at least two more showing two men kissing, but I have yet to see two men kissing in public.

How can this be described as representative of anything?

I don’t care, people can do what they want, but why normalise something that is clearly confined to minority circles?

“how is aggressively pursuing a policy of eliminating straight white males from advertising reflecting society?“

Erm….

But that is exactly what is happening to straight white males in society! So maybe they have it spot on

But South Asians, who are more numerous than Africans (and South Asian Hindus, Sikhs and Christians are more affluent) are seriously underrepresented.

I agree.

Do they care?

Dove using ordinary models wasn’t woke, it was targeted marketing.

Endless adverts with successful African men and sexy blonde wives is not targeted marketing. There are almost no mixed race couples. Most women reject African men in particular closely followed by Asian men. The most common mixed race pairing in the UK is white men with Oriental wives, and even this is a very small number.

If those ads reflected reality we’d see a tiny handful of Asian couples in the background, and a lower number of black couples. The majority would be white couples. This is not what we see.

The articles states quite clearly what the problem is and it was written by a mature insider.

Well, it was something they didn’t do back in the good old traditional days celebrated in the article!

Why would advertisers encourage obesity?

Because it means their adverts are working?

On GB News a while back there was an add showing a WHITE couple lying on a Norfolk Feather bed – I am not making this up – honest!

It is/was quite possibly one of the last. It has not been shown recently.

Perhaps it was eradicated?

Oh look, woke companies are on the public’s shitlist. Another shock headline.

Is this The Daily Sceptic or the The Daily Bleeding Obvious?

🤠

The easiest way to avoid brands that do “woke advertising” is to avoid brands that spend a lot on advertising, unless there’s no comparable product.

In the 1980’s I either read something, or watched a documentry, about the cost of advertising, a TV commercial minimum was a million quid, back then a million quid was an eye watering amount of money. It struck me as way too much money to be added to a products bottom line, so I refused to pay for those products.

Same thing happened with prosessed food, saw a piece in a trade magazine about pumping salt water into meat the title was “why sell meat when you can sell water” I very rarely ate processed meat ever since, unless there’s no alternative, or it’s too much hassle to make your own version.

My line on “too much hassle to make your own” has shifted so much I’ve invested in a pressure cooker for canning my own food for long term storage. The starw that broke the camels back on that was pickled red cabbage & pickled Beetroot, ‘tater ash’ is not the same without some picked cabbage or beetroot, every brand I’ve tried in the last ~12 months is now full of sugar. Some are so bad it doesn’t even taste pickled, and raw beetroot tastes minging, so we pickle our own now. It’s quite a large investment, large pressure cookers are only available imported from the US ~£300, and jars are ~£2 each, but they last a long time.

AdBlocker Ultimate & UBlock Origin are invaluble tools on my PC, I would be driven mad by adverts without them, I can’t even watch youtube on the TV since the ads drive me mad.

Re Alan Jope – WEF luvvie, UNICEF luvvie, vice chair World Business Council for Sustainable Development, World Bank something-or-other, etc. etc. say no more!

Do we really want these unelected globalist navel gazers (i.e. bankers spelt with a W) running our lives? How can we stop them, they’re ubiquitous in every-bloody-thing, including government.

Excellent post Imp.

cheers Hux, MrTea won the tread for me early on with

It reminded me of my early school days, getting teased for my plimsoles when the fashionable thing was addidas trainers, I asked my parents to get me some, this prompted my dad to sit me down and give me an invaluble life lesson about the cost of stuff and how “fashion victims” spent more of their money on brands that don’t really provide anything useful for the massive extra cost. Nobody teased me about my plimsoles after I pointed out they were fashion victims wasting money while they still couldn’t run faster than me.

Good post.

I’ve had Adblock, Ublock, Privacy Badger and Ghostery on my P.C. for ages and never see ads.

The only ads I ever see on Youtube videos are the ones actually embedded in the video by the creator themselves, for example AwakenwithJP.

Watching Youtube without the aforementioned browser extensions is ghastly!

My new game is to try and count mixed race and diverse families as I fast forward the adverts.

I play ‘spot the white family’…. Don’t win very often.

That wouldn’t make a good drinking game!

Interesting, useful stuff, thanks.

“Andrew expands this idea in his paper The Empathy Delusion, showing that marketers tend to think they have advanced levels of empathy and a superior moral framework.”

It has been my observation that the bien pensant often lack any kind of empathy – they have sympathy, but sympathy is not the same as empathy. Hence they are completely incapable of appreciating the other side of any argument.

I worked for a Unilever company early in my career, Birds Eye Walls frozen food. I was very proud to be working for an International ‘blue chip’ giant. And I was proud of all the other brands and companies that they owned. Batchelor’s (at that time) Lipton, Omo, etc. I will get a pension from them in a few years time. And now we have the virtue signalling, politically correct posturing of Dove adverts. Which leads me on to M&S, another company with which I had an association of which I was proud since I worked for one of their suppliers and visited their HQ in Baker Street many times. I bought all of my underwear from them, not to mention work suits and trousers (they always fitted perfectly, no need to try on) for many years. Then there is Gillette, Nike, Coke, Vauxhall, all brands that have decided to alienate every day people in search of ‘woke’ consumers. Well I’m not woke, and while I still consume, I don’t consume any of the above named brands if I can help it. Although a Magnum (ice lolly, Unilever) on a sunny day is hard to beat, but I generally try to buy the own brand knock offs.

Recently I have had to spend more time on LinkedIn than I would ever choose to spend (which would be zero if I could). I believe a significant part of the corporate wokeness machine now exists solely for the purpose of justifying the roles and salaries of the individuals perpetuating it. Changing a company’s logo every second day to represent the cause du jour cannot have any measurable effects on profits. Yet you see small businesses who must barely be scraping a profit after lockdowns employing people for this purpose. I’m also shocked by how aggressive some of the posts are becoming. One calling for any company employing people educated in Russia to be boycotted for example. Attaching such bigotry to a brand without apparent concern surely shows the direction of travel is rather more worrying than merely going broke.

As a researcher and former brand manager from a bygone age, I can clearly see how when just 1 in 25 people in ads should be black, 4 Asian, and 20 white (to reflect the UK population) that the current wave of ads don’t just fail to connect – they massively antagonise – undermining brand values.

Yes, but advertisers don’t get together to decide who’s going to cover off the minority in their ad.

From the point of view of an individual advertiser, they have a long history of all white ads. They’re being diverse within their own ad stream, not so much the ad stream as a whole.

Don’t they watch ads themselves…do they live in a vacuum? Of course they do…

Do they know they are perpetrating woke nonsense? Of course they do…

It is relentless, multiple issues, omnipresent. I cannot believe it is a case of companies copying so as not to be left out of the latest fashion – and there is distinct whiff of Govt involvement. It is co-ordinated.

Every… every… TV ad has one or more black person, or black/white mixed race family – but seldom Asian despite this racial group being four times bigger.

Vegetarian foods ‘help the planet’.

Responsibly resourced.

Carbon neutral/Net Zero

Organic

Sustainable.

No plastic.

Electric cars.

Windmills ‘just happen’ to be in the background of documentaries and other shows.

I avoid these products where possible, but it is difficult to find alternatives.

I’m sick of it.

It should also be considered the charade is not just about selling product but is social engineering… propaganda to ready us for ‘the Great Reset’.

I reached a tipping point recently and emailed Marks & Spencers customer services to ask if their store was now only for black people. I pointed out the fact that 86% of people in the UK are white yet almost 100% of their in-store billboards at our local M&S feature so called ‘BAME’ people. Their response?

“Marks & Spencers is committed to diversity.”

..that’s exactly it though, it’s not diversity is it? Diversity is about inclusion…

now we have white people, particularly white couples with white children being excluded from 99% of advertisements…

Its amazing how many random people I meet while out walking the dog who mention it……it obviously annoys a lot of people…

This can all be traced back to when they demanded the golliwog was removed from the marmalade jars

This fine feller from Oxford likes to wear a Robinson’s Golly round his neck.

The BBC wanted to interview him, but insisted he took the Golly off.

There was no interview. He told them where to shove it.

If the company’s woke, just say nope.

M&S & The Body Shop have both lost my custom thanks to them forcing women to share toilets with men.

Marketers think they are superior – ha, ha, ha. I remember some I used to know: greedy, nasty with superiority complexes. The new ads are probably some form of Dorian Grey in action.

I have decide that next time I am in one of those dreadful queues for the ladies loos (and just what DO some women spend ages doing in there? Are they loosening their stays or something? I’m in and out in 30 seconds) I am going to go and use the gents, which never seems to have a queue. If challenged I shall just say, as I imperiously hoik my bosom, “I identify as a man, actually”, followed by a hard stare. I think I’ll get away with it.

Really very simple. If I like the product and/or need the product I buy it. I don’t give a monkeys if it’s woke, unwoke, saving the planet or the source of every emission ever created. However if I see a product pretending to save the planet, rescue polar bears, rebuild the Amazon rainforest and it’s blindingly obvious it’s a complete toss off, I’ll avoid it if I can. There are always choices

I no longer watch any advertising whatever or any posturing, patronising arrogant pitches and lectures on consumer behaviour and Carbon Zero BS from Corporates, who are merely looking forward to their “Stakeholder”consumer ‘policing’ roll in the planned ‘New Tyranny’ and to locking us all down in a digital dystopia, just to earn themselves a place at Schwab’s Top Table (next to Prince Charles!).

When Gillette started woke advertising, I ditched their razors after 30 years’ worth of use. I needed to buy some new blades and I went to a different company for a whole new razor. If a brand starts pushing a political agenda, I simply look for an alternative brand. I wish businesses would stick to their job.

Of course, Old Man Gillette believed that all companies should gradually merge until one giant company ruled the world.

Please, sir – I think I’ve spotted the problem!

I did like this bit:

It’s worth bearing in mind that many researchers like to suggest that younger generations have both a better moral framework than older people and are more likely to buy sustainable brands, without any evidence for either in terms of actual behaviour.

I spluttered on my coffee after reading that. They should really get out more if they believe that, or they could try just looking out of the window. Teenagers especially might have some instagram or tiktok inspired moral framework, vague and nebulous; here today gone tomorrow, matching the latest outrage. But they do love their Nike (as one example), and what a paragon of virtue that company is!

Young people have always been idealistic and cause-driven, but young people grow up.

Very true; people in marketing apparently do not.

https://www.bitchute.com/video/H73YEuKII7R4/

At WEF, Pfizer CEO admits to PLAN / INTENT to reduce world pop. by 2023 by 15 or 50%

Hard to hear. Really sounds like 50% which is a little ambitious, surely?

“Today the dream is becoming a reality.”(run time: 4 min. approx.)

Jesus Christ!

This clip plays for 54 seconds.

“When we started in ’19 our aim, my team … was to reduce the number of people on this planet by 50% by 2023. Today I can say we are well on the way to achieving our goal.”

Al Bourla speaking to Schwab at the WEF.

So my constant assertion on here that these so called “vaccines” have been brewed to a recipe is correct. Furthermore, Pfizer are wholly complicit in the depopulation agenda.

There is something in these injections that has not yet been found but Bourla knows that millions and up to 3 – 4 billion are going to die within the next twelve to eighteen months. Perhaps I should have typed “scheduled to die.”

There are some posters on here in for a firkin reality check.

I feel sick. My stomach is turning over. I am stunned. No pretence here.

The CEO of Pfizer, recorded on video, has come right out in front of a live audience and admitted that he, and his team, have been working on reducing the world population by 50% by 2023. And since 2019. “Pandemic? My arse,” as Jim Royle would say.

God help us!

Something has clearly been removed between “in the world” and “by 50%”

Ignore this video – it has been falsely edited. It is a spoof.

More on the nanotechnology in the vaxxes

This time from Daniel Nagase, who worked with the Canadian doctor who exposed the high death rates in newborns in a maternity hospital. This doctor was interneded in a mental health facility. Nagase is his friend.

Rumble interview here.

https://rumble.com/v11go0d-watch-dr.-nagase-reviews-images-from-covid-vaccines-shows-no-elements-of-li.html

Transcript here.

https://expose-news.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Transcript-Dr.-Daniel-Nagase.pdf

Read up on codon optimisation, causes misfolded protiens, the mRNA jabs were all codon optimised, misfolded protiens are basically prions, read about prion disease, it depends where in the brain they get to as to what disease gets diagnosed.

One researcher got prion disease from airborne particles prepping samples from a petri dish onto microscope slides.

These things can be airborne, as can the freaking spike protiens, aka shedding.

A good source is Kevin McKernan on twitter, he’s definately covered the codon issue, and the shedding issue, mite have to scroll down a bit it was a while ago. He was R&D lead on the human genome project at MIT, very switched on genetics chap.

https://twitter.com/Kevin_McKernan

Another good source is Kevin McCairn (retired neuro scientist) if you have time to work though his veeeeery long streams at mccairndojo.com, I’ve been too busy sorting the garden to keep up so not sure where they’re up to atm.

Green Flag anyone?

Nearly out of battery so I’ll link it rather than bang on.

Winner is pretty representative of a recovery mechanic…..NOT!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KN5TqebpL6Q

“Modern marketers seem uninterested in such commercial logic. They see themselves as on a much higher moral mission. The result is ‘brand purpose’, which in reality is therefore just virtue signalling and an indulgence that they feel they deserve – it’s all about them”

We’ve noticed. It’s gratifying that the most egregious examples have backfired spectacularly, eg, Gillette.

There’s been an obvious doubling-down on woke advertising since as recently as 2019, judging by the ads in programmes recorded back then. Now there’s a majority of black actors in ads, a complete over-representation that even the most oblivious of viewers cannot avoid noticing.

We actively avoid watching adverts on tv, so if companies were hoping to push their products and messages to consumers, i suspect they’re failing, and wasting their money.

Please, show a copy of this survey.

a copy of the text sent, please.

Thanks

I think that most people buy what they are used to. Here the milk I buy is inside a Tetrapak container full of white phrases in green background (difficult to read). Most of them is non-sense about carbon & al. This brand is available for more then 30 years.

Bill Hicks on Marketing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHEOGrkhDp0

Many thanks to DS for publishing this article. The ‘woke’ BS, ramped up horrifically since the Globocrap coup commenced over two years ago is clearly linked.

I despise ‘woke’ wherever and whenever it appears.

About two years ago Yorkshire Tea came out in favour of BLM. I was a user, occasionally, of their tea bags (ordinarily I use loose tea) and I wrote to complain. They replied. And told me to FO. I will never purchase their products again and wrote telling them so.

Does advertising gather pounds from me, absolutely not and never has? Do I like logo’d products? Rarely. Probably the only item where I bother about the brand is a watch yet I am as happy to wear a ten quid Casio as a brand costing hundreds – there is a limit after all. I own about 40 watches.

On the subject of which, one of my favourite brands – Christopher Ward has gone over to the dark side with all this climate change crap – ethically sourced watch straps made from tyres washed up from the Torre Canyon, or some similar BS. Do me a favour – I want to buy a watch not your politics. That’s another company deserving of its place in history.

Gillette and their anti-man campaign? Hilarious and laughable. The sheer stupidity and lack of intelligence was off the scale. I haven’t bought their products since. Very popular in the £shops now though 😀 .

MSM advertising? Totally ignore it now. We don’t watch scheduled TV, we scan for the occasional nugget and record for later. When the adverts come on I pick up a book and press ffwd.Multi coloured families? Yes I have noticed. So obviously woke that’s why ffwd is deployed.

Radio? I won’t use the BBC for anything. Commercial radio? I occasionally put this on in the car and switch off when the adverts start.

As far as the advertising industry is concerned I am an absolute desert.

To all those on the Woke bandwagon – P O, I am not interested in your politics just as you are not interested in mine.

The most despicable “profession” on the planet. Even more duplicitous than doctors and politicians. Edward Bernays has a lot to answer for.

Totally agree that TV ads have become disproportionate in their use of BAME actors. Almost every ad these days is almost exclusively BAME, which is a bit disproportionate to the actual population’s ethnic makeup. It would be nice to think that actors were chosen on their acting ability and suitability to the character, but apparently not, first the actor must come from the BAME community. But hey, who takes any notice of ads anyway. Time to put the kettle on.

I will not buy B&J ice cream, Hellmans or the chocolate that has woke nonsense plastered over it. The job of a business is to make profit for it’s shareholders, nothing more.Trouble is shareholders are big pension funds and they are just as bad, so who looses out? Savers that want a decent pension.

Always good to vote with your wallet

The item about mixed race couples and the over-representation of ethnic minorities in advertisements rings true. I am sick of seeing Afro-Caribbeans advertising everything but very few Asians represented, although the latter are a larger proportion of our population.

There are a few brands I won’t purchase from on account of them pushing their “virtue” on me. I just want to buy a pair of trousers, not a political lecture!

OMG why do you give Ricky whatever or woke a minute of your time?

Perhaps we should go to the root cause – why do people feel the need to virtue signal? What is missing/wrong in their lives that this void exists. Please can a psychologist work this out and then how to fix it, to save the rest of us from them!

I’ve recently cancelled decades long subscriptions to a slew of cookery magazines because I just don’t feel they represent me – a white woman in my 50s – anymore. Every photo shoot features BAME or mixed race families. All children are mixed race or Afro Caribbean and the only white men allowed are a handful of celebrity chefs but never more than one or two in every issue. The BBC magazines particularly have gone full BLM. From reading the magazine you would imagine Britain was 85% black or mixed race, 10% white and 5% Asian. I’m not racist and have many long standing black friends, some with mixed race kids -hell one of my god children is mixed race! – I’d just like magazines and ads to look like this country not like some millennial’s woke wet dream!