In a recent article published in the New York Times, the science writer Zeynep Tufekci argues that the B.1.617.2 “Indian” variant appears to be more transmissible than even the B.1.1.7 “Kent” variant, and could therefore be “catastrophic” for parts of the world with low rates of vaccination.

As a consequence, she argues, vaccine supplies should be “diverted now to where the crisis is the worst, if necessary away from the wealthy countries that have purchased most of the supply.”

While asking rich countries to share their vaccine supplies with poorer countries surely makes sense, one of the points Tufekci makes in support of her argument is based in error. Linking to Our World in Data’s chart of UK daily deaths, she writes:

Britain had more daily Covid-related deaths during the surge involving B.1.1.7 than in the first wave, when there was less understanding of how to treat the disease and far fewer therapeutics that later helped cut mortality rates. Even after the vaccination campaign began, B.1.1.7 kept spreading rapidly among the unvaccinated.

In other words, she’s saying that the higher mortality rate observed in Britain’s second wave, following the emergence of the “Kent” variant last November, constitutes evidence that new variants can pose serious and unforeseen challenges to national healthcare systems.

However, it simply isn’t true that there were more COVID-related deaths “during the surge involving B.1.1.7”. As I’ve noted before, the chart showing deaths within 28 days of a positive test (to which Tufekci links) gives a very misleading impression of the relative severity of the first and second waves.

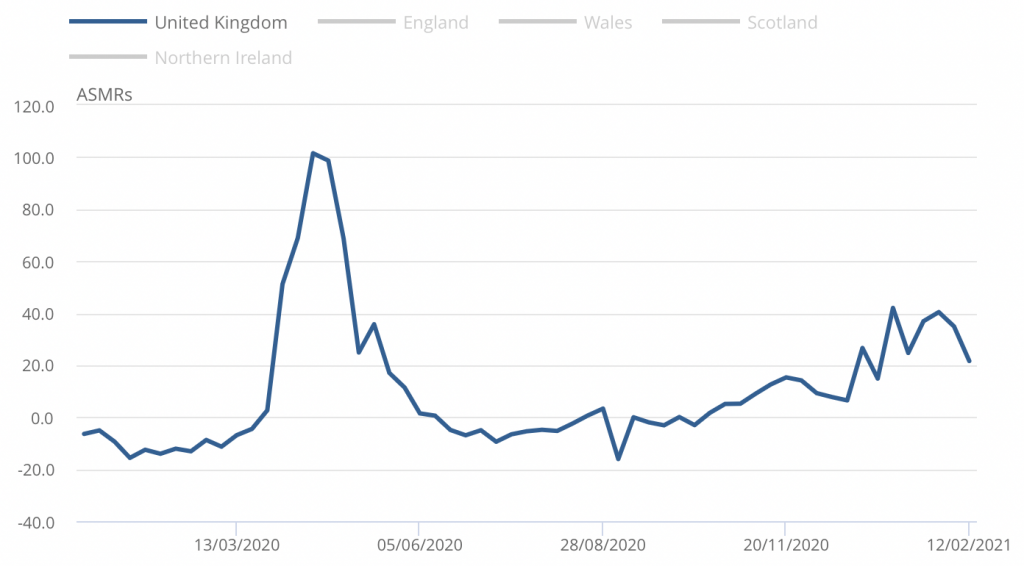

The correct chart to use is the one the ONS published on 19 March, which plots age-adjusted excess mortality up to 12 February:

The peak weekly mortality in the first wave was 101% higher than the five-year average. Yet in the second wave, it was only 42% higher.

What’s more, cumulative excess mortality was 483% in the first wave, but only 328% in the second wave. Of course, the latter figure is an underestimate because the series stops in mid-February. However, extending the series forward wouldn’t make that much difference. Indeed, there were nine consecutive weeks of negative excess mortality in March, April and May.

Countries with low rates of vaccination should certainly remain vigilant with respect to new variants, but decisions need to be based on the best available data – and that means age-adjusted excess mortality wherever possible.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Most of these “respected” news sources are now full of liars paid for by billions$£ bent cash eg NYT, Telegraph /nuki etc

Ello…ello…ello… Lockdownskepticals?

Wondered where I’d gone to…?

I’ve been a tad preoccupied this last month or so advising a one-per-centerer on bolthole peasant revolt avoidance strategies… why? Well tis plane for all to see if you’ve been awake from the deliberate fog permeated by the MSM programming play this last decade or so.

So where are we at, right now…? As we ping along into flaming June. Well, China’s chomping at the bit to roll into Taiwan and assimilate their semiconductor business…

Meanwhile you boomer retired leaches are still using up far too many carbon credits as you cling-onto your ever dwindling middle-class aspirational lifestyles…at the expense of the younger woke generations chance of the ‘American dream’ diversions… Trust me, these super woke vegans are gunning for your ‘extravagances’ so on display during those loadsamoney roaring 80s/90s/Noughties… Something just had to give… didn’t it?

Tis why this killer-flu-bug ‘variant fear mongering’ is here to stay for evermore till 50% of the globes useless eaters are gone… and as there are billions plus chicom mouths to feed in the east for sure ramping up hate against China remains useful as we head for a mini hot war.

BoJo and Co’s current mandate is to keep running the BUILD BACK BETTER aligned strategy – keeping the ninety-nine percenter pleblicities indoors, locked-down local on a five months off three summer ones on basis… minimising and trashing their ICE car use – critically keeping them very much away from frivolous jet travel as much as possible, till only three airports for the 99% of Brits are left come 2030.

This is why emphasizing deadly endless mutations of corona are vital. Kill Bill made it clear… everything living top-o-the-food-chain-primate wise does so by burning black gold oil.

So every autumn/winter adifinitum from now on, the depop/defrag strategy mows along, continually culling eating out, larger family celebrations and needless indulgent weddings, all reducing water and food wastage and those all-important carbon credits consumed.

Let that sink in…this decades ago plandemic play is the godsend move for first world politicos – a black-swan convenient ‘act of god’ tragedy – mitigating population overshoot once and for all.

You self-indulgent consumerist fvckers didn’t take climate change seriously enough in droves did you? So a new more frightening bitch slap was required. Let’s review what 2020 corona time delivered:

• Energy use destruction and reductions in imported oil by keeping the 99% locked at home

• SMEs and factories closed killing operational capacity, destroying loner-term orders and use of raw materials

• Move to wave like shutdowns to maintain a prison like order in areas were uprisings related to low wages could flare

• Hide the increasing problem of unemployment, failing retail and businesses behind a terrifying public health problem

• Allow politicians increased emergency plandemic control crushing any descent and the once enjoyed liberties.

So I’ll finish with an economic question… What if you persuade 80% of the over 60s in your country to take an experimental gene therapy that within 18-24 months down the line leads to their permanent global exit? Plus add in 40% of their gene-pool offspring 20 to 30 something generation opting unwittingly to become sterile?

Would this help balance up carbon credit consumption availability, and what’s left on a finite asset planet for the 1%?

As you were…

You sum it all up in one pithy post. Yes, it’s always been about depopulation and a massive depopulation, delivered by injection at that.

People can’t say they weren’t warned, cuddly Bill Gates told us years ago what his vaccines were really for, yet the zombies still flocked to the “vaccination” centres for the lethal injections.

Bill will be laughing his socks off, it must feel so good that his literally breathtaking plan is really coming together.

I have been thinking along the same lines for a while now, there is no way to replace the energy of “black gold”. Fossil fuels are the only reason humans have expanded so much and in our usual short term outlook way, we spaffed it all on big cars and keeping ourselves toastie warm. The 1% know it is running out and the public disorder when the people realise it will seriously effect them. The global warming narrative has failed (some of it is even true) and they have moved on to the new fear. By killing us slowly over a number of years whilst blaming the virus, they can avoid the looming catastrophe.

So do you ATL believe that the holy vaccines work against scariants, or don’t you?

If you think that we BTL are scared of scariants, think again. We’re sceptics, you see.

Saying that countries with low vaccination rates should be especially vigilant of variants suggests LS firmly believes the jabs have an impact in reducing infections.

Pfizer, Moderna and AZ don’t claim they do. But LS apparently knows better.

Gimmie a break! The New York Slimes!

What next? The BBC as a reliable source?

What she actually got wrong was… “when there was less understanding of how to treat the disease and far fewer therapeutics that later helped cut mortality rates.”

Very few are using any sort of ‘therapeutics” to treat the disease in this country, despite the research into hcq, D3, ivermectin, steroids etc.

At a local care home 6 residents became ill with c19, three were given high dose D3 and survived, one of whom none of the staff thought would make it, three weren’t and died. Anecdotal evidence I know, but the only real difference was three had one GP and the others another.

Good levels of vitamin D reduced Covid deaths (whatever Covid really is) by 94% in a trial done in one hospital in the US, I forget the details of where. Not too surprising really, as vitamin D has been known for many years to reduce drastically flu deaths, but they are never going to tell you that now, are they?

More disinformation from the MSM.

“While asking rich countries to share their vaccine supplies with poorer countries surely makes sense”

It doesn’t. Ivermectin makes sense. https://trialsitenews.com/ivermectin-for-covid-19-in-peru-14-fold-reduction-in-nationwide-excess-deaths-p-002-for-effect-by-state-then-13-fold-increase-after-ivermectin-use-restricted

I dunno, though.Any poor sucker can have my snake oil.

India isn’t a ‘poor’ country, even if it’s treated as one when it suits – but, for the record, it did better when using Ivermectin than when it was using the snake oil.

It’s a rich country where the poor are very poor and as such can die of a whole lot of things very easily. Certain commentators are only interested in highlighting one particular apparent cause of death at the moment, for their own reasons.

The NYT is every bit as bad as the BBC for spouting propaganda!

It’s the New York Times.

Officially – and publicly – compromised by the CCP.

…’nuff said.

second peak was mainly vaccine deaths of the hyper-frail

they knew this was a possibility – the side effects can be quite nasty at any age – they are likely to kill you if you are in your last year of life

I expect that’s why AZ at least was banned in most places for the oldest

However, even with 2 covid seasons and the vaccine deaths, 2020 was only the worst year since 2008 and every year before 2008 was worse

https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/deathsintheukfrom1990to2020

I expect the flu jab and general improvements in care had built up a load of frail people that copped it in 2020. Some from covid, some from stress/depression/lockdown/closure of NHS and some from vaccines

2021 is looking to be back to ‘normal’

I wonder if that’s a reason AZ didn’t test on the over 65s, or for cross reactions to medicine. Oldies take quite a lot of that I expect.

I think the trials were rushed, they tested on young and healthy people to see if anything really obvious cropped up. To me, what cropped up was that the side effects of the vaccine were worse than the effects of covid on that cohort. I was expecting a decent proportion of the 600,000 in their last year of life to die if they jabbed them and I think that’s what happened.

Essentially, there has been no proper trialing – all this post-hoc observational stuff is just fog and bull-shit – shown up as such by the ARR. The trials weren’t ‘rushed’. Bluntly – proper trials haven’t happened. The data is fragmentary and partial as a result.

For anything like this stuff, extended RCT (not curtailed) examination is necessary. Yet the majority of the population haven’t been told that they are taking part in a trial, and that, judged by normal standards, the level of associated side effects are remarkably high in comparison with properly approved vaccines.

I have been concerned by the number here parroting the government propaganda line that the ‘vulnerable’ need the snake-oil. Like a hole in the head. It hasn’t been subjected even to its own miserable testing standards for this group – and, even before Bhakti sad it more scientifically – I wouldn’t touch it with a barge-pole.

I don’t think anyone ‘needs’ it – given its side effects. Either you are young and covid doesn’t affect you or you are old and the vaccine might finish you off.

Even after the first ‘trial-like’ testing, it was obvious from the side effects that getting a dose of the real thing would be preferable in the overwhelming majority of cases.

There may be a sweet spot between being young and being hyper-frail where the stats work but how will we ever know without proper trials?

Precisely(%) Rick,

Even the Mengelian Big Parma admit stage 3 trials are due to be completed in 2022.

So as you say this innoculation programme is just a series of Clinical (cynical) trials.

And don’t forget to mention they are not Vaccines as this Wuhan Flu has not been isolated which is the accepted definition of a vaccine.

“second peak was mainly vaccine deaths of the hyper-frail”

That is the most likely explanation for the sudden cliff-like peak. Nothing else works. Any decent analysis indicates this “Shhhh!” explanation.

Essentially, the snake oil was creating a further concentrated ‘dry tinder’ peak.

Another, more general, thought should be borne in mind about this sector of the population and deaths. We know that, given the unknowability of actual ‘Covid’ death numbers, that mortality has been heavily age-biased. Beyond that, take out those related to nosocomial locations (care homes and hospitals), and you have an even more unexceptional infectious event, given that true death rates from it are probably only around one fifth of those reported.

yes – this is all about how you count deaths and what it means to die of old age. Dying of old age is often being pushed over the edge by something you would have brushed off if younger.

If we consider ‘what pushed someone over the edge’ then normal colds would account for about 250k deaths a year out of the 600k a year total. But we don’t consider it like that for normal colds, just for covid.

If we considered covid as we consider normal colds then 95% of people put down as covid just died of old age. The number of non-hyper-frail who died of covid is in the thousands – its just bugger all to get excited about

“ its just bugger all to get excited about”

The fundamental underlying point, which had became obvious to me by last June after doing the most basic analysis that anyone calling themselves a ‘scientist’ should have absorbed.

my realisation moments were

1 – diamond princess

2 – age related death data from Italy early March

stuck it in a spreadsheet and found that you are as likely to die of covid ‘as anything else’ in a particular year. it was just a complicating factor in deaths of old age

no data has changed my mind since because the data supports that position

I had to do a LFT to work in a building last week. They let me get on with doing the test while they went off and got me a coffee.

I can confirm my arse crack is covid free.

Same, they wandered off assuming I knew how to do my first and only test, my tongue is safe, rejoice!

This is an illustration of the dire state to which journalism has descended. The apotheosis of what Nick Davies terms “churnalism” (Flat Earth News – one of the seminal analyses of modern journalism – the repetition of received chinese whispers and the abandonment of truth and investigation).

“the B.1.617.2 “Indian” variant appears to be more transmissible than even the B.1.1.7 “Kent” variant”

Of course – all the ‘variant’ stuff is made up. Mythical nonsense. Would the UK had had the effects of the ‘Indian’ variant, rather than the results of government plus assorted sociopathic arseholes’ meddling! We’d have had a lower death rate than the world average.

Retarded vaccine Minister Zahawi blames the care home catastrophe on lack of testing – rather than on sending infected patients into care homes.

To me this is the core of the issue.

1 – have a decent plan

2 – panic, create a new plan on a whiteboard

3 – clear out nhs into care homes

its all about the panic. the reason they ripped up the decent pandemic plan was the same as the reason they biologically attacked the care homes – stupidity and panic

now does it really matter if some care home residents die a few months early? Yes – if those numbers are used to pretend this is a wider issue than care homes and the NHS and used to justfiy locking me in my home.

Noah is over-simplifying things. ASMRs are not “the correct chart” for measuring Covid related deaths. As Sarah Caul says in the ONS article he links to:

“There are several ways to measure mortality and to fully understand we must look at this in a number of ways.”

The same article goes on to say “Analysis of all-cause mortality allows us to examine the impact of the pandemic not only from deaths due to COVID-19 but also excess deaths that have occurred as a result.”

This is a handy perspective but the NYT article seems to be referring to deaths caused directly by Covid which is different (this is not entirely clear). If that is true, then the deaths where Covid is given as cause on the death certificate would seem to be more relevant. It is certainly one of the perspectives to take into account. (I would say that the death certificate figures are better than the “within 28 days figures” but they track the death certificate figures very closely and are something of an international standard.)

In any case the relevant bit comes near the end of the article and is a very minor aspect of the overall story. So it was not significantly misleading whatever you think is the right chart to use.

Aren’t they all playing the same game where nations are brainwashed into believing things are at bursting point elsewhere by being shown horrifying images of Covid-swamped countries where anyone who dares to walk outside is immediately struck down with the most horrifying respiratory disease ever, but when you are actually in that country, there is nothing to report