It’s well-known that flu-like illnesses are seasonal, and COVID-19 seems no different.

What is not well understood is what drives the seasonality. The flu season is in the winter months so the obvious candidate is temperature. However, closer analyses have tended to rule out a simple role for temperature, not least because seasonality occurs in places with very different climates.

Other potential candidates are sunlight (including UV radiation) and humidity. None is completely convincing, though sunlight has been shown to have a direct role in stimulating the immune system.

Now there’s a new kid on the block: pollen.

Martijn Hoogeveen is an independent researcher who has been exploring the role of pollen in driving seasonality. Pollen is known to be triggered or inhibited by meteorological factors. Hoogeveen explains:

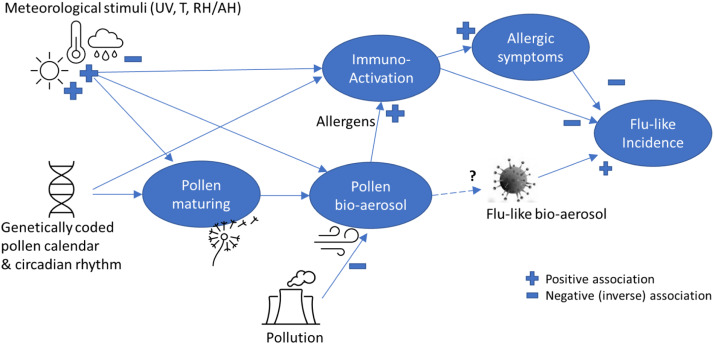

Meteorological variables, such as increased solar radiation and temperature – among others the absence of frost – not only trigger flowering and pollen maturation, they also affect the pollen bio-aerosol formation: dry and warm conditions stimulate pollen to become airborne. Rain, in contrast, makes pollen less airborne, and cools the bio-aerosol down. Very high humidity levels (RH 98%) are even detrimental to pollen (Guarnieri et al., 2006).

The main idea is that the pollen plays a further, significant role in stimulating the immune system (such as when it causes hay fever), which has a strongly inhibiting effect on flu-like viruses. A further, more speculative idea is that “anti-viral phytochemicals in pollen” could directly inhibit viral aerosols in the air.

Hoogeveen illustrates the relationships.

Hoogeveen observes that temperature by itself is not a good predictor of the flu season in the Netherlands.

The onset of the flu season, from mid-August in the Netherlands, coincides with an annual peak in hot, sunny days and is still in the middle of the summer season. … Although temperature strongly correlates with flu-like incidence (r(226) = −0.82, p < 0.0001), it has a negligible effect on ΔILI, weekly changes in flu-like incidence (r(224) = −0.02 n.s.), also when corrected for incubation time. Therefore, it seems unlikely that temperature has a direct effect on aerosol flu-like viruses and the life cycle of a flu-like epidemic. In line with this, temperature is also not a good marker for the onset or the end of the flu season. In the Netherlands the end of the flu season (Ro < 1) can coincide with an average temperature that is close to 0 °C and the start of the flu season (Ro > 1) can coincide with temperatures as high as 17 °C.

However, solar radiation and pollen, both of which are known to have an impact on immune activation, have a much stronger relationship with flu-like illnesses.

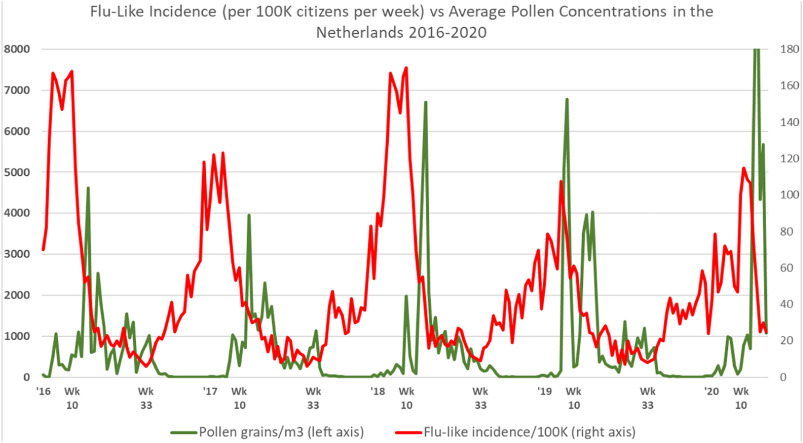

The following graph shows some of Hoogeveen and his team’s results, depicting the remarkable inverse correlation between flu-like incidence and pollen concentration.

Hoogeveen explains:

Flu-like incidence starts to decline after the first pollen bursts. Moreover, flu-like incidence starts to increase sharply after pollen concentrations become very low or close to zero. This is a qualitative indication of temporality. Furthermore, we can notice that the first COVID-19 cycle behaved according to pollen-flu seasonality, at least does not break with it.

In formal terms: “The correlation for total pollen and flu-like incidence is highly significant when taking into account incubation time: r(222) = −0.40, p < 0.001.”

Hoogeveen identifies some thresholds that appear to trigger (or at least signify) the beginning and end of flu seasons.

We found that our predictive model has the highest inverse correlation with changes in flu-like incidence of r(222) = −0.48 (p < 0.001) when thresholds of 610 total pollen grains/m3, 120 allergenic pollen grains/m3, and a solar radiation of 510 J/cm2 are passed. The passing of at least the pollen thresholds preludes the beginning and end of flu-like seasons.

In the years covered in the study (2016-2020), Hoogeveen observed that “the pollen thresholds are passed in week 10 (± 5 weeks), depending on meteorological conditions controlling the pollen calendar and coinciding with reaching flu-like peaks, and again in week 33 (± 2 weeks), marking the start of the new flu-like season”.

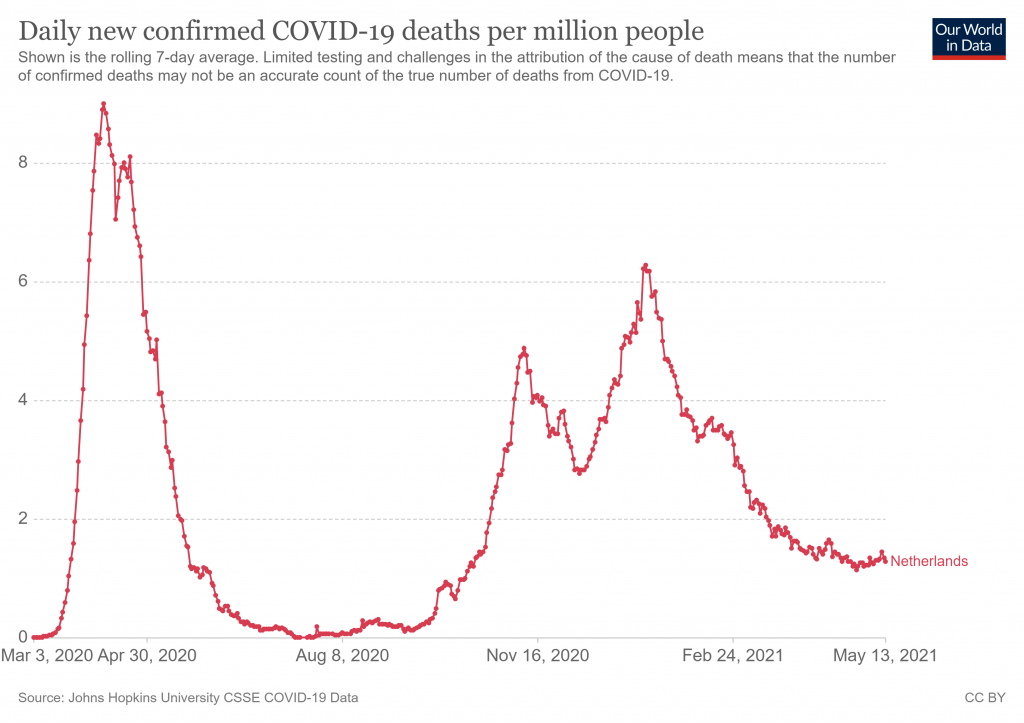

Hoogeveen doesn’t indicate how this model has fared in 2021 so far, though week 10 or even week five doesn’t appear to line up with the Covid peak in the Netherlands this winter (see below). It would be interesting to know the pollen concentrations over this time, and Hoogeveen’s thoughts about this.

Sceptics, who frequently point out that epidemics of Covid, just like those of other flu-like illnesses, are seasonal and surge and decline independently of policy interventions, will welcome research into the nature of this seasonality.

One unanswered question is the role of acquired immunity in triggering the peak and decline. If seasonality is the dominant factor then a peak may not have any relationship to the current level of population immunity acquired through infection and the fact that a wave has come and gone doesn’t tell us anything about how close we are to a protective level of population immunity. On the other hand, if seasonality interacts with population immunity then a peak and decline may tell us something about how far the population is immune.

Looking at the graph above, it seems to me that for 2016-17 in particular the peak (though not the decline) occurs well before there is any signal in the pollen. This suggests there is something besides pollen contributing to ending the exponential spread of the virus that year. Population immunity is one obvious candidate for this.

It’s also worth noting that in this model pollen and other drivers of seasonality are understood to operate primarily through their effect on the immune system. In this sense then the interaction with population immunity is built in.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Unfortunately, a lot of things are correlated with the seasons. It shouldn’t be too hard to test the pollen idea, though. The case for humidity is that humid air, as in summer, causes aerosols to grow and sediment out of the air, along with their viral load, due to gravity.

Or simply the body doing some spring-cleaning?

Occam’s Razor gives the answer.

Covid is spread via aerosols. Aerosol concentration is higher in areas where lots of people congregate – particularly indoors in winter when the windows are closed to keep the heat in.

Our ventilation systems are primitive. Very few of us have MVHR mechanical ventilation in the house enforcing a strict air change, let alone at work or in the shops and public buildings.

In summer vents are opened, as are windows and the air change level increases. And people start getting hay fever…

Late summer days are correlated with high pressure, still air that doesn’t move very much, high humidity and no rain to wash things out of the air.

If you’re a hay fever sufferer or and somebody who suffers badly from respiratory illnesses – get yourself a PassivHaus.

We measure air pollution externally, but amazingly nobody bothers to use those devices internally within buildings over winter. If we measure external and internal air pollution and merge those curves I suspect we’d find a correlation.

‘get yourself a PassivHaus’, for hayfever? A couple of air purifiers might be several hudreds of thousands of pounds cheaper.

This is the reason the hot countries and southern states have had “waves” of deaths, as they usually do in hot periods. In those climates, people tend to congregate indoors and not all air conditioning systems are equal. Ideal conditions for all kinds of diseases to spread, not just Covid. This was known from Sars all those years ago.

Nonsense. People are indoors with windows closed as much in summer as they are in winter.

At what Latitude?

What fascinating hypothesis.

Seasonal as flu and covid clearly are, it is always tempting to look for direct correlations with sunlight, daylight, humidity, and temperature and so on. But I’ve long wondered whether the virus levels, or at least human susceptibility, are not in themselves heavily influenced by some other factor which is itself driven by seasonality, rather than there being a direct link. More likely, it is probably influenced by several such factors, which makes spotting the trends in data difficult.

One obvious question is whether there is any correlation between individuals who suffer from hayfever (and maybe rhinitis, I’ve suffered badly from both at times) and covid susceptibility.

There is also an obvious question to be asked about the influence of air quality. Covid appears to have been worse in areas of poor air quality. Notably, down here in the South West it has never really taken off. I’ve always thought maybe sea air has something to do with it, but why not pollen and other natural factors?

Another hypothesis of mine is that an individual’s immune system varies over time, such that they may be effectively immune to a flu-like/SARS virus at one moment, but susceptible say a few weeks later. Perhaps such temporary immunity may be picked up by repeated contact with small quantities of the virus. If so, then a population may reach effective herd immunity at one point in the virus spread, and the infection rate will be seen to decline, but once those temporary immunity levels decline sufficiently the virus is able to take off again – hence ‘waves’, or multiple peaks.

Just me thinking aloud.

Definitely worth pursuing the idea that there may be an inverse correlation between allergic disorders & susceptibility to respiratory viruses.

Note that asthmatics are UNDER represented in Covid admissions & deaths. If correct, I could come up with several hypothetical reasons for this.

1. Asthmatics often use inhaled corticosteroids, which are anti inflammatory & mimic endogenous cortisone. Prof Peter Barnes & others hypothesised that it was the ICS which was protective vs Covid19 & the trial of inhaled budesonide was a triumph.

2. Those with asthma have an immune system bias favoured Th2 cytokines & this milieux doesn’t favour virus infecting. I don’t find this attractive because it’s full of holes. Some asthmatics are made very ill merely in respond to one of the dozens of viruses which cause the Common Cold.

Its got to be the first. They are regularly using an inhibitor.

I have no medical background, so as soon as we get into technicalities I’m floundering!

The pollen hypothesis outlined in this article seems to be getting a lukewarm response here, but it’s so refreshing just to see these ideas being put forward and discussed. What a great pity such a climate of openness hasn’t been more prevalent during the covid saga.

The asthmatics one is interesting – a bit counter-intuitive possibly, as one might imagine that any respiratory issue might increase risk from SARS/covid. Reminds me of the oft-quoted observation that smokers are at less risk of developing the disease (although I understand that if it develops to the point where they need ICU treatment their outcomes are less favourable). I recall some New York doctor (I think) saying that his covid patients appeared to be exhibiting symptoms analogous with altitude sickness. Now I remember from my trekking days that it was often said that smokers were often good at altitude, in dealing with the thin air. From my observations, it was the wiry individuals, especially women, who did best on the high trails. And of course, wiry fit individuals, especially women, are at lower risk from covid.

A rambling post, by what I’m getting at is that I feel there is an awful lot we could have learnt about SARS2/covid just by observing what has been unfolding around us, commenting, swapping ideas, and stepping forwards – but we haven’t, because the medical establishment (for want of a better phrase) have deliberately closed the debate down, leaving only a few brave individuals (usually retired) to speak out, who collectively lack the critical mass to make swift progress.

Still, like Sisyphus rolling the stone, it’s just a question of keeping going.

Agree, there are a lot of things that could be observed and correlated but they are intent on their models and ignoring everything else.

Purely anecdotally, I had covid or something suspiciously similar in December 2019.

I had a fair case of hay fever during the 2020 tree pollen season, which I don’t normally get. I had a second wave during the (late) grass season which has happened before.

This year not so much, though I had a coughing fit yesterday while surrounded by rape fields – I could smell the flowers. Rape pollen is heavy and tends to drop rather than fly into the air but a lot of the smell comes from the flowers and leaves – think school cabbage. Complex sulphur-containing substances: pollen isn’t the only thing emitted by plants.

They used to have pollen counts on the weather forecasts but I haven’t seen one recently. Then there’s all the other air pollution so aa complex picture.

Interesting academic speculation, which after all might assist the authors cash flow. However, it’s well known that a decent amount of exposure to Ultra Violet B is good for us as it kicks off the production of vitamin D. The other thing that came up last year – can’t remember who it was, but was a proper specialist – was the possibility that pollen related allergies could actually reduce vulnerability to virus attacks, on the basis that there is only so much surface area in our nostrils, and that if a certain number of cells are ‘occupied’ with dealing with the pollen, they would not be accessible to the other enemies. Don’t know if that’s true, but it seemed like a reasonable idea.

Don’t take it too seriously, otherwise they’ll be dishing out large amounts of pollen on the basis that it’s good for you.

I’m lukewarm about the pollen season idea, though there are attractive features about it. There’s a long running concept of populations of T-helper cells, which in mice appear to divide into two major populations. Th1 & Th2. The former revolves around interferon release & the latter around cytokines associated with atopy & allergy, specifically IL-4, IL-5. Furthermore, there is proposed to be mutual inhibition, such that the immune system can be biased to respond to allergens or to non-allergic stimuli. In such a world, allergic events might suppress autoimmunity & perhaps responses to respiratory viruses.

Many will recall the “hygiene hypothesis”, which sought to explain why modern humans appear to suffer from much greater prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis & atopic dermatitis, with the notion being that we’re no longer exposed to Th1-biasing organisms in our childhood. Bolstering this idea there were numerous studies in the 1980s & 90s purporting to show that rurally raised kids, especially those living on farms, were less likely in adulthood to suffer from the allergic triad of illnesses.

Against all that was the realisation that the human immune system is not crisply divided into this yin yang Th1/Th2 bias and sometimes both were found to be elevated clinically. I’ve not been a fan of animal models of diseases from which they don’t suffer. Instead, I preferred to use human cells & tissues preferably taken from volunteers with the disease in question. This approach can work well in inflammatory disorders but not so well with Alzheimer’s

I think its true that allergic reactions to say a food product can appear to make an individual more responsive to other allergins like tree pollen. My wife is a good test case for this. Take certain older cheeses out of her diet and she can sit in the garden without problems.

However re virus, I think its more likely that someone suffering a bad dose of tree pollen allergic reaction is far less likely to be bothered by a pesky coronavirus. Quite frankly it doesn’t stand a chance.

Correlation is not causation.

I read an interesting explanation of ‘herd immunity’ over 12 months ago. Its not fixed. It varies with human movement and mixing, especially at certain times of the year. In September for instance there is a peak of house sales, kids starting new schools, people starting new jobs sometimes in new locations. This mixing can reduce a previously stable herd immunity. This hypothesis discounted all the external seasonality factors and explained increases in virus effects simply by looking at the movement and change of make up of human populations.

It also produces good correlations.

Do I believe this is ‘the’ explanation? No , the are holes in all these theories when you look closely enough.

The earth’s lower atmosphere contains trillions of particles , including ‘things’ that virus can hitch a ride on. They move around as weather flows occcur , with the winds. They rise and fall with humidity depending on the weather effects. Its a catastrophic system.

The only thing I think we can say with some certainty is that particles get caught in our buildings and when its colder or wetter we stay in those buildings more often; so any virus hitching a ride on those particles is more likely to find a nice warm host. QED. Which is why of course ‘lockdowns’ were the most stupid policy imaginable.

NB As an aside, anyone thinking ‘long covid’ is bad should suffer with pollen over many years, it can debilitating.

Always worth mentioning the Fred Hoyle hypothesis. https://www.panspermia.org/panfluenza.htm

The lower atmosphere contains quadrillions of virus, without any need for extra-terrestrial input. More indeed than there are stars in the universe. They can fall to the surface due to wather events at any time. The vast majority are not injurious to human health, not so much to do with our immune systems but because of the nature of the virus. But some can be. It takes 2 weeks for a virus to typically circumnavigate the equator depending on weather patterns.

I continue to find the idea that SARS2 having to board an airplane quite ridiculous. How thick do you have to be to get a job on SAGE?

It’s always said that respiratory viruses spread much more easily in winter because we all spend much more time indoors, where we infect each other. Well this may be true in some communities, in rural areas for example. But take a large city. Is there really that much difference in the time city dwellers spend inside and outside in winter and summer? I would guess that they tend to spend a large proportion of their time indoors, irrespective of the season. Thus we might expect to see similar levels of virus infection in winter and summer. But that doesn’t appear to be the case.

Your hypothesis about variable levels of individual immunity is fascinating and surely needs exploration.

As regards lockdown being the most stupid policy imaginable. Well my Cornish grandmother, and I’d wager all her grandmothers before her, knew that fresh air was the best antidote to respiratory illnesses. But apparently our medical establishment know differently. I’d better not write any more or the moderators will be after me.

I suffered badly from rhinitis for many years (after enduring hayfever as a child) – debilitating with a major effect on your life, which other people just don’t understand (‘Just blow your nose!’ ‘You’ve got a cold, stay away from me.’)

I do not believe anyone requires any greater opportunity to catch a respiratory virus than he is granted by commuting on crowded public transport. London, with its famous “underground” railway, must be a haven for infectious disease.

There is precious little seasonality in commuting, barring the tendency to have a couple of weeks’ holiday, during the summer.

Indeed, my point exactly. So why winter peaks in cities?

A very interesting article and although the pollen hypothesis might not be proven the authors first cited article (shown below),clearly spells out the similarity with flu and flu pandemics. The current epidemiological models indicating transmission and herd immunity cannot explain that temporal pattern at all. Why did the first pandemic wave stop at all as there were so many susceptible left indicated by the second wave in most places? Why don’t we have an explosion of cases among the unimmune in the summer? The crux is to show which is the seasonal influence driving the pandemic and perhaps pollen theory is an interesting suggestion but probably other factors too. Could it be that population immunity in general (not specific antibody dependent)against respiratory viruses fluctuates according to season?

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.28.21252625v2

Comparable seasonal pattern for COVID-19 and Flu-Like Illnesses

“Interestingly, all over Europe, the COVID-19 cycles were all more or less in sync with the Dutch COVID-19 cycle and thus ILI seasonality, independent of the start of the first cycle, the severity of lockdown measures taken, and given that herd immunity is not yet reached”

What it tends to suggest is that much of our current difficulty is caused by crass over-simplistic, over reaction to matters that are not well understood. They might sound clever, but they’re not, some might say.

This raises the point, that a lot of viruses are spread in indoor settings. If you have periods where people are seeking shelter from either the cold or the heat, then more will by default become sick during these periods, surely?

If you add mass testing for one of these viruses only, then it’s very easy to have an epidemic.

Well, yes; the more you look, the more you’ll find. Unless they’re suffering from amnesia, many people will have a reasonable idea of what sort of phases of activity, physical environment etc, have resulted in them being infected by one thing or another.

I am surprised how almost everyone, sceptical and otherwise, seems to accept that Covid is seasonal and that the season is winter. It is a new virus and we only have 18 months evidence to go on. Yes – almost all European countries had an outbreak at roughly the same time last winter, but the pattern was different in the USA, with some states peaking in the summer, and the European outbreaks this year have less of a pattern with UK and Spain peaking in January but Italy and France peaking in April. This could equally be explained as simply when the virus and new variants arrived at different places. The main reason for assuming seasonality seems to be that it is similar to flu but that is quite a bold assumption.

I am not saying it isn’t seasonal – just that the evidence is not in yet and some scepticism is in order.

I think the other common cold coronavirus are seasonal so this one likely to be too

They seem to be, but it’s easy to fall into the old trap of assuming what the exact link is due to temporal correlation, or which route to follow in trying to understand why. After all, school terms are seasonal, as an example. Fortunately, we have a degree of automation to deal most of the problems.

Fair enough. That is a good reason for thinking Covid may be seasonal if/when it settles down to a pattern. But I don’t think we can draw firm conclusions at this stage when the data are so limited and not very inconsistent.

That’s meant to be “not very consistent“! I wish there was a way of editing comments.

It is normal for some places to peak in the summer. Ivor Cummins went over this in one of this videos – https://odysee.com/@IvorCummins:f/crucial-viral-update-jan-4th-europe-and:c

The rise of respiratory infections in India starting in April/May is also completely normal. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/figure?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0124122.g004

We are over a year into this now. We cannot keep saying that we don’t have data or we don’t know enough. We have a whole ton of data and we know more than enough. Sars-cov-2 is really not that new of a virus, but it is completely unremarkable and uninteresting.

When you say it is “normal” I guess you mean normal for flu? We can’t know the normal yearly pattern for Covid given we have only had one complete year. Yes – the data are compatible with the hypothesis that Covid is seasonal like flu. The data are also compatible with the hypothesis that it isn’t seasonal or that the season is something other than winter. I really don’t think a year is a ton of data on seasonality. Seasonality means repeats the same pattern every year. So one year is essentially one data point. To say it is unremarkable is to assume your conclusion. If it proves not to be seasonal then it will be remarkable and interesting.

I did wonder last year if hay fever might have contributed to the spread through those affected coughing and spluttering more, and of course avoiding going outside when pollen is high. Too simple perhaps? My worry with this type of study is that someone somewhere will take it as an excuse to concrete over even more of our ever diminishing natural green spaces, we know how much developers prefer ripping up a forest compared to converting a brownfield site…

Bugs are not seasonal, we are. Vitamin D levels would seem to be the obvious suspect.

Shaman (2010) demonstrated quite clearly that it’s air humidity that drives seasonal pandemics:

https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1000316

This was generally accepted up to 2020, when we threw the entirety of public health precedent out the window.

My mask will protect me from hay fever this year. After all if it can protect me from a tiny virus, it’ll work against a pollen grain thousands of time bigger.

What seasonality? How do we know that it is still around? What conformation?

I’m not sure if seasonality really is well known at the moment. Apparently we’d known this before, but we erased our memories at the start of 2020.

The panic mongering currently going on about India’s “variant” is in fact completely in line with its flu season, for the states beginning in April. Yet the media is completely ignorant of this fact. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0124122 If we look at India’s all-cause deaths there also nothing out of the ordinary to see there.