When Professor Neil Ferguson and his team at Imperial College London have been challenged on their model’s miserable failure to predict the pandemic death toll in Sweden they have always pushed back saying they didn’t model Sweden, disavowing the work of the team at Uppsala University which adapted their modelling to the Swedish context. But it turns out this is not exactly accurate. Phillip W. Magness explains on AIER:

In the House of Lords hearing from last year, Conservative member Viscount Ridley grilled Ferguson over the Swedish adaptation of his model: “Uppsala University took the Imperial College model – or one of them – and adapted it to Sweden and forecasted deaths in Sweden of over 90,000 by the end of May if there was no lockdown and 40,000 if a full lockdown was enforced.” With such extreme disparities between the projections and reality, how could the Imperial team continue to guide policy through their modelling?

Ferguson snapped back, disavowing any connection to the Swedish results: “First of all, they did not use our model. They developed a model of their own. We had no role in parameterising it. Generally, the key aspect of modelling is how well you parameterise it against the available data. But to be absolutely clear they did not use our model, they didn’t adapt our model.”

The Imperial College modeller offered no evidence that the Uppsala team had erred in their application of his approach. The since-published version from the Uppsala team makes it absolutely clear that they constructed the Swedish adaptation directly from Imperial’s UK model. “We used an individual agent-based model based on the framework published by Ferguson and co-workers that we have reimplemented” for Sweden, the authors explain. They also acknowledged that their modelled projections far exceeded observed outcomes, although they attribute the differences somewhat questionably to voluntary behavioural changes rather than a fault in the model design.

Ferguson’s team has nonetheless aggressively attempted to dissociate itself from the Uppsala adaptation of their work. After the UK Spectator called attention to the Swedish results last spring, Imperial College tweeted out that “Professor Ferguson and the Imperial COVID-19 response team never estimated 40,000 or 100,000 Swedish deaths. Imperial’s work is being conflated with that of an entirely separate group of researchers.” It’s a deflection that Ferguson and his defenders have repeated many times since.

In fact, though, as Phillip points out, it is not true to say that the Imperial team never estimated 40,000 or 100,000 Swedish deaths. Hidden away in a spreadsheet in the appendix to Report 12, published on March 26th 2020, are the team’s estimates for other countries including Sweden. The projections are expressly intended to encourage those countries to follow suit with social restrictions. They write:

To help inform country strategies in the coming weeks, we provide here summary statistics of the potential impact of mitigation and suppression strategies in all countries across the world. These illustrate the need to act early, and the impact that failure to do so is likely to have on local health systems.

The predictions for Sweden are up to 90,157 deaths under “unmitigated” spread (Uppsala projected 96,000) and, under “population-level social distancing” (lockdowns), 42,473 deaths (compared to Uppsala’s 40,000). So, contrary to their repeated denials, Ferguson’s team did make predictions for Sweden very close to those made by the Uppsala team who adapted their model, and those predictions were just as way off. Sweden’s Covid death toll at the end of the first wave, on August 31st, was 5,821.

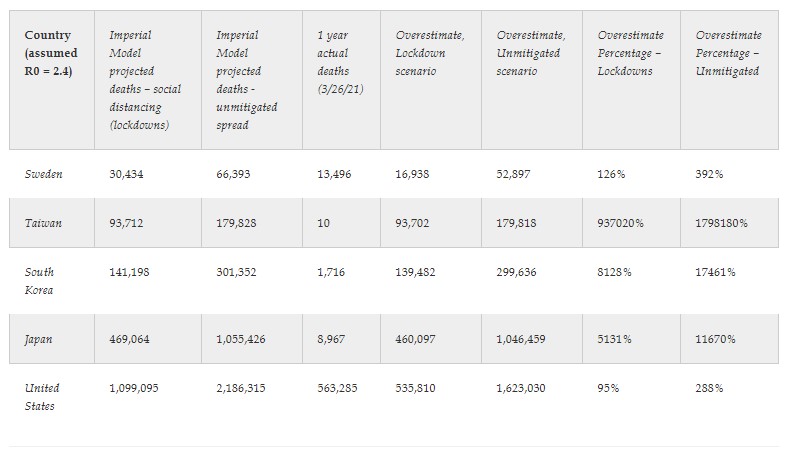

Phillip summarises further failures of the Imperial modelling in a table showing four non-lockdown countries (Sweden, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan) and the United States (most of whose states imposed a lockdown in the spring) with their one-year death toll and how it compares to Imperial’s projections.

It’s worth saying, though, that the models for the ‘unmitigated’ scenarios predicted the deaths to occur over the course of a few months, not a whole year including another winter flu season. There will be another ‘wave’ of deaths every winter, possibly from (or with) COVID-19 if it remains the dominant respiratory virus (and if we keep on testing for it). If we keep on adding the deaths over several seasons then of course they will eventually reach the predicted figures. But that wasn’t what the models were claiming to show and would be a case of making the evidence fit the model.

The AIER article is worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The real question here is: Why did Asian countries like Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, who have much higher population densities than Western countries, have such low death tolls? Could it be that the reason is that they didn’t artificially inflate their numbers as part of a scaredemic?

All three countries have good reason not to trust China nor believe anything it says. They were also particularly speedy at closing their borders to China. And may already have had a lot of immunity in their populations due to previous exposure to SARS.

Japan’s population also in the main eats a better diet than most Western countries and although it has an elderly population they have high vitamin D levels and therefore their immune systems are well equipped to deal with a virus like SARS-COV-2.

Fair point.

More likely according to Yeadon is their prior exposure to SARS in 2003 giving their population natural immunity. This makes any comparison with Far East countries problematic imo

Fair point.

Comparisons between countries are fraught with difficulty – there are just too many variables involved (including data garbage).

Indeed. Another one of the many sins of govts everywhere is to have been complicit in generating more garbage data making it harder for anything useful to be discovered about covid – their claims to care about public health are hard to take seriously.

I read somewhere that Japan’s % of elders who are obese is minute (4%) compared to UK (29%) and New York (40%). Or something like that. Would be interesting to a graph worldwide plotting obesity rates vs covid deaths.

Yes I was about to say that. There simply are no fat people in Japan. I’ve travelled to Tokyo many times and the population is uniformly lean. It’s not possible to imagine without seeing it!

Sadly no matter what evidence is presented to them people like Ferguson, along with Bojo, Whitty, etc. are never going to admit they got it catastrophically wrong.

Or that they fudged the numbers in order to change the fabric of society?

Ferguson is famous for getting things catastrophically wrong, there is nobody better at turning a drama into a crisis. Yet even with his history of causing untold suffering with his ‘models’, there is absolutely no self-doubt or self-examination, where there should be massive guilt and shame there is arrogance and mis-placed confidence. And all under-scored and approved by Johnston.

It he worked in industry he’d have been sacked for gross incompetence.

However he might then have gone on to become a Consultant (seen it happen)

“…parameterising.”

Thus, not only does Ferguson do incalculable damage to the reputation of ‘modellers’, but to the English language, itself.

True.

Covid is itself a disease of language: safe, surge, social (as in ‘social distancing’), case… and dozens of other words that have been denatured and corrupted by Covid-cult liars.

What is clear is that Kneel is not a scientist but a politician. Lying dissembling, deceiving, calculating to protect himself and not a truth seeker.

Interesting to note, in the spreadsheet, that the lowest modelled numbers of infections/deaths for the UK are when enhanced social distancing of the elderly is implemented. Higher modelled numbers are given for social distancing of the whole population.

The Great Barrington Declaration suggested protecting the vulnerable. The Imperial modelling appears to be supporting that strategy.

Except in this paper

https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk:8443/bitstream/10044/1/77735/10/2020-03-26-COVID19-Report-12.pdf

… with this linked data

https://t.co/yBD0z5rhc4?amp=1

… on 2020-03-26, they made this set of predictions for Sweden.

https://twitter.com/PienaarJm/status/1400699456434102274/photo/1

…

Which forecast for “Enhanced social distancing of elderly” with an R of 2.4, which is what was sampled in Sweden, that there would be 16.1k deaths.

They’ve had 14.5k.

Why continually write articles, basically lying about people’s research?