Last month a pre-print was published that showed COVID-19 antibodies in South Africa had reached remarkably high levels. It was ignored by most of the media, but given the concern over the South Africa variant being “more transmissible” and “evading vaccine immunity” it shouldn’t have been as it gives an indication of what we might expect from the variant.

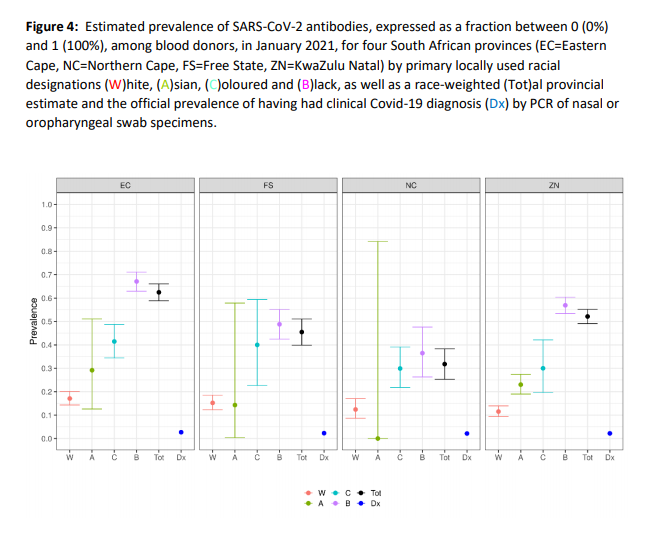

Extrapolating from antibody testing on blood donors, the researchers found antibody levels of 63% in Eastern Cape province (EC), 46% in Free State (FS), 52% in KwaZulu Natal (ZN) and 32% in Northern Cape (NC). These figures were between 15 and 22 times higher than the percentage of the population that had tested positive for the virus to date.

Major differences were found between races. Seroprevalence among black donors was consistently several times higher than among white donors, which the authors put down primarily to the difficulty in social distancing among the lower income black communities. As black people form the majority in the country, this meant seroprevalence among black people in each province was slightly higher than the overall seroprevalence (see graph above). Seroprevalence among white people was between 10% and 18% – figures notably similar to those found in European countries pre-vaccination. The authors attributed that to the effectiveness of social distancing and lockdowns, which they considered white people in general to be in a better socio-economic position to observe.

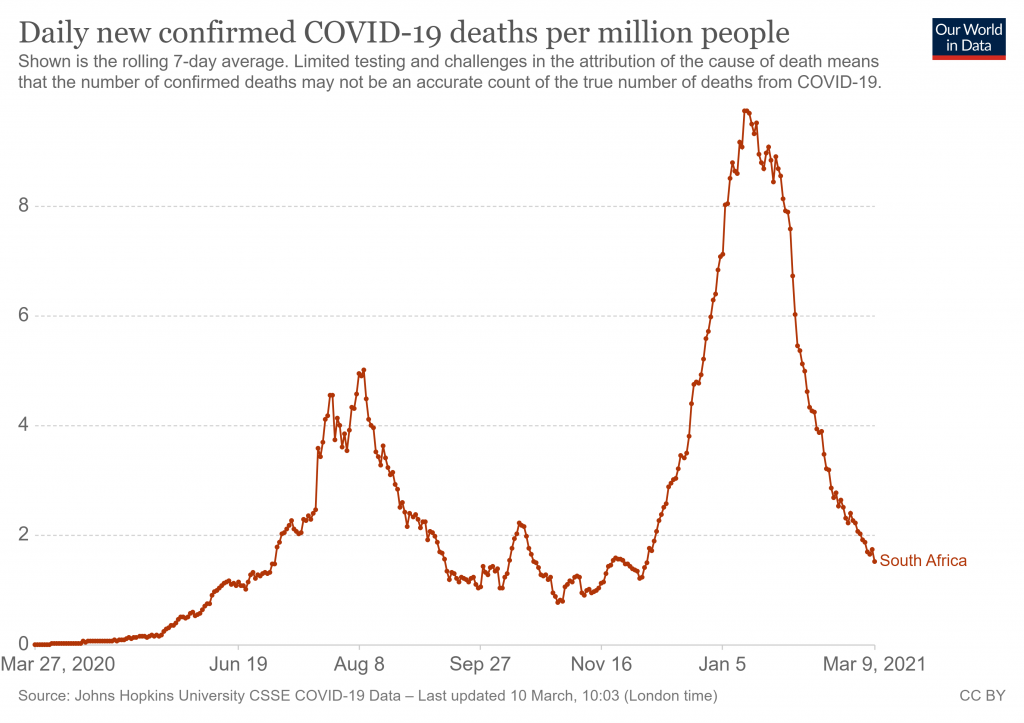

Be that as it may, it is notable that, notwithstanding the lack of vaccinations, the “more transmissible” variant and, as the researchers acknowledge, little effective social distancing, cases and deaths peaked and sharply declined from mid-January. As of March 9th, the Covid death toll in South Africa stands at 858 per million, less than half the UK’s 1,842 per million. This may under-count the true death toll, though there is no evidence of a great deal more deaths in the country that have gone unreported.

What caused this decline? With antibody prevalence as high as 63% in some areas (let alone other forms of immune resistance, such as T cells) collective/herd immunity has to be a prime suspect. Another factor may be the fact that January is the middle of summer in the southern hemisphere (though, interestingly, that didn’t prevent the spike in the first place).

Worth noting, though, that there is nothing unusual about a COVID-19 epidemic going into spontaneous decline, even with antibody prevalence much lower than in South Africa. Places with few restrictions such as Sweden, Florida and South Dakota have also seen spikes fall almost as quickly as they have risen, and at much lower antibody levels – and in the middle of winter, too. Spontaneous decline is in fact the norm for a COVID-19 outbreak, not the exception, as we saw when new daily infections in England peaked ahead of the national lockdown on all three occasions. Happily, the South Africa variant does not appear to alter this basic behaviour of the virus.

Today, March 11th, we mark the anniversary of the WHO declaring a pandemic and the beginning of the steep slide into the eternal lockdown in which we now find ourselves. A good moment, then, to reflect on whether it has all been worthwhile and what it has achieved. If South Africa is any indication, the tragic answer is: nothing at all.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Seconded! I won’t be buying one either! I’ll stick with my duster until it runs into the ground then ill buy a brand new one hours before the supposed ban and then run it till I run into the ground!

But they will tax your old pile of junk to Kingdom Come to get you to scrap it. ——-This reminds me off that old joke where a guy is facing the firing squad somewhere in the middle of Mexico and he is asked “Have you any last requests Senor”?–The poor guy replies, “Can I have a cigarette”? The guard hauls out a packet of fags and slides one out for the guy.——- With the ciggie in his mouth he asks “Can I have a light”? ——-The guard barks “”Sorry Amigo, only one request.”———–With everything Green we have no choice. We don’t even get a last request.

I’m actually in ireland but what happens in the uk is usually taken up here too.

Whatever they do I’m sticking with it!

F-em and their toy battery cars, people in rural ireland need rugged diesel vehicles and unlike the UK won’t just lay down and take it!

You had the chance to be out of the EU but your fellows fell for the bribe. So you might fall for the green bribes as well.

Maybe our streets will resemble those of Cuba

God willing, we’ll still have the choice!

Good summary of the madness of that racket.

I grade that as A****, or 100% in English.

I don’t understand why more MPs don’t understand. Is it scientific illiteracy, venality, messiah complexes or just plain stupidity?

It’s plain and simple greed

C’mon, all you really need is a PPE degree to know everything necessary to run a country. Everyone knows that!

/s

“There is also some doubt as to whether the U.K. National Grid would cope with the increase in demand for electricity by 2050.”

There is no doubt – it won’t. Firstly the work would need to be underway a decade ago, but it’s not even underway or planned now.

This is why mouthpieces for the Grid, tell us we will have to get used to not having electricity available all the time, and why domestic and business customers are being bribed to use less electricity at certain times.

It will require a huge amount of copper wire, which in turn needs copper extracted from copper ores. Given the global requirement for copper to make all the BEVs, chargers, grid equipment, power lines, electric appliances to replace gas appliances, there will not be enough copper being produced to meet demand.

There are no signs of scaling up copper ore mining to meet prisoectuve demand for copper.

The amount of capital, labour, manufacturing, construction, transportation, energy, labour to upgrade the grid, build power stations, make other changes in infrastructure is not available to meet the schedules.

It is very important to understand the reason why no preparations are being made, none are needed because Net Zero = zero energy and zero industrial economy.

“It is very important to understand the reason why no preparations are being made, none are needed because Net Zero = zero energy and zero industrial economy.”

And let’s not forget ‘net zero’ equals zero carbon and WE are the carbon.

I think you’re right about cable sizing, but actually a lot of it is aluminium, expect when more flexible cable is required. E.g the buried distribution cable along my street is 3-core aluminium, with short copper 2 core connected it into the houses (3 phase on the big one, and singles to the houses). So the use of (relatively expensive) copper is kept to a minimum.

Aluminium is also used for aerial conductors owing to its relatively low weight.

But regardless, BEVs are crazy.

The pylon cables have a steel wire core and aluminium outside. This is not about weight, it is strength! The load on those cables is many tons of tension, much more than the aluminium could stand.

Producing Aluminium needs vast quantities of electricity! Your suggestion about aluminium cables is largely correct, but there isn’t enough of that either! You see there really is no answer to the stupid grandstanding of politics. Britain is already virtually bankrupt. The next move will be to take all your money, and then we will all be dead!

When they say that they want to transition to EVs they are obviously lying. Not enough low carbon electricity, not enough raw materials, not enough investment in the grid. What they really mean is that they want us to transition to no car.

Sadiq Kahn is currently the chair of C40 cities. Their stated intention is to cut car ownership in London by at least 2/3 by 2030. ULEZ is just the start. Road pricing is also planned despite his recent denial. None of the politicians are going to stop it. Time for civil disobedience. Death to ALL the cameras.

The head of the National Grid (Steve Holliday) warned about 10 years ago —–“We are going to have to get used to using electricity as and when it is available”. ——It has long been known by politicians of all parties imposing this energy rationing climate garbage on us that there won’t be enough electricity go around, which is why they are bribing the idiots among us to get a smart meter so help curb use under the guise of not having an estimated bill. When you rely on part time energy like wind there won’t be enough and the planet savers KNOW IT

It is only recently that I was looking at the viability of the various electric option.

I immediately rejected pure EVs for all the reasons stated above.

I then looked at hybrids, and in my naivety I hadn’t realised there were two types.

The plug-in hybrid has a decent range on a battery and has the back-up of a petrol engine in the likely event of running out of leccy when you are nowhere near a charger.

Then I looked at the price! Of course you have the cost of both an engine and a battery.-nothing I could find under £30,000. But I think you can push these after a breakdown.

So the other hybrid type seemed ideal. You could just about manage a trip to the local shops on battery alone, and had the ever present petrol option was there for serious journeys. They are also attractively priced.

Then whilst listening to a radio programme about electric power, the presenter mentioned that sales of hybrids are to be banned along with petrol cars Curses.

Apparently hybrids are an even bigger con than full evs!

Those who have them just run them on petrol all the time because its lazier than having to faff about keep charging them, this means they spend more time running on a small inefficient petrol engine than on electric which leads to lower miles per gallon (also having to drag the weight of batteries around) using the engine constantly trying to charge the battery adds to the load and mpg problem.

The reason they sell well is government subsidies, fleets buy them by the hundred and save thousands in tax rebates then the workers just use them as petrol cars and never bother charging them! To get full efficiency you need to charge them and use them in electric mode as much as possible to get the promised savings or they’re no better than ice cars!

They are not all the same. Whether plug-in hybrids are any good depends on the way they are used by the owner. They are only worth it if they do a lot of short distance trips, e.g. The non plug-in ones do have the benefit of regenerative braking, along with engines that are more thermally efficient than other petrol engines, exploiting the presence of a traction battery so that they can both work together on the odd occasion that maximum power is required.

I’m a private owner of a Toyota hybrid – no financial interest in the trade, but I’ve had a couple of them over the last 6 years.

Don’t be conned by regenerative braking, they have normal brakes too. You do not recover much energy, but it sounds good!

It depends on how it’s driven, but the friction brakes normally only do much at low speed. I’ve never had to replace a brake pad on mine – they always record the measurements re that on the service records. Incidentally, regenerative braking may be quite new on the road, but it’s long been used on some railway locomotives, including most of the modern electric trains. In that case, the on-board output goes back into the grid for use by other rolling stock, or further afield, depending on the system concerned.

It is a good marketing ploy, like I heard a British Gas ad saying that their heat pumps were cheaper to run. They did not say what they were comparing it with.

One disquieting thing I heard recently (admittedly it was someone in the US) found that his particular brand of vehicle’s regenerative braking didn’t illuminate the brake lights on his vehicle, not too much of a problem during the day, but he thought at night it was far harder for someone behind his vehicle to register that he was slowing down.

My next door neighbour is shameless. He confirms that he chose one (a Mercedes SUV) as a company car solely because of the tax advantages. He never even drives it except on holidays as it is used by his wife for transporting the kids around.

A wise choice, for most people. I’m not interested in EVs either, although I’m content with hybrids, using electric transmission. It’s true that they can’t be towed on all four wheels except at low speed, as it’s not possible to disconnect the traction motor mechanically from the drive shaft. Some EVs use rear wheel drive as well (at least with front wheel, they can be dragged along with the front wheels being off the road – but in reality, most of them would need a trailer to take the whole thing off the road).

The one I have now is a Toyota Yaris, which has a relatively small Li ion battery. The previous one used a NiMH one – heavier and smaller capacity).

I think that the real issue to do with electricity supply for charging EVs is local distribution (the Distribution Network Operators domain), rather than the National Grid. Not that long ago, the DNO in my area replaced a lot of buried cable due to existing faults, and their local transformer as well. Thus I’m aware of it’s capacity, based on the cable rating and that of the transformer. A short story about it all here: https://youtu.be/LS8VFhRMsYY SSE did the work to replace dodgy cable, with no plan to upgrade it to cope with increased demand. However, the current BS 7671 does suggest that some kind of remote control so as to curtail demand could be used. I’m guessing, but the use of “SMART” control might become necessary, to stop everyone doing it all at the same time. They don’t advertise that.

Re the generation capacity on the grid, there are many hours during which there is plenty of spare, as long as the demand can be managed. https://grid.iamkate.com/

Re. the demand, remember we are meant to be moving all heating to electricity at the same time – that will increase demand significantly

JohnK

Whilst you make some useful points, the grid only has excess capacity when the wind blows strongly and the sun shines without too many clouds. The excess capacity is thus not real capacity, and in winter, night, or other times your electric heating will take a great deal of power. On average each property has 1-2kW available 24/7. The system works by diversity, that is all the loads are not present at once. But electric heating and car charging drives a coach and horses through that, as they are both constant large load for long periods. To work we need to approximately triple the Grid capacity, and probably 5x for the local distribution. That is the “secret” problem the politicians ignore because they are completely oblivious to any engineering!

I can’t think why I would want one, or what benefit I would get from owning one..or how it would benefit anyone else..it’s one of the biggest virtue signalling rackets going in my opinion.

..that’s besides the horrendous environmental cost..and I say this, not as someone who believes the whole green zero nonsense, but having seen numerous programmes, photos and articles about where the lithium, cobalt, graphite, manganese etc come from…..the labour is mainly African, slave or poorly paid, includes children and leaves the land in those countries devastated…and looking like hellscapes….that’s a real environmental impact…not the rubbish they try to ‘sell’ to us……

The environmental costs of these, turbines and solar panels is humungous. We will be exporting vast CO2 output to the 3rd world.

However, for Greens (well, they are totalitarians, so this makes sense) the end justifies the means. So mining neodymium causes cancer for Chinese workers? Who cares? There’s plenty more where they came from? Kids mining Cobalt in the DR (ha ha ha) Congo? Again, plenty more where they come from.

Not to mention, the roots of environmentalism eh?

https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1155&context=hist_fac

and Rupert Darwall’s “Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex” available at all good booksellers.

And of course, Delingpole’s “Watermelons”.

”Why I will never buy an electric car”

Will many individual private people ever ‘buy’ an electric car? increasingly the whole electric car business seems to be moving to lease or subscription schemes. The EV business seems to not just be a change in the motive power of the car but a whole move away from the old pattern of car ownership and secondhand sales. With ICE cars there was a pattern of sales down the secondhand market such that low income people and new drivers could readily pick up a perfectly usable car at a relatively low price. Somehow it just does not look like this pattern is going to work for EV’s?

Are private people really going to happily purchase 3 year old ex leasehold EVs? These ageing EV’s will have a limited battery life, nobody is going to want to be the one holding an EV when it gets to the end of its battery life. Many EVs have the battery built in so you cannot just change it, when the battery goes the car is finished. My understanding is that our ability to re-cycle EVs is not properly developed and so it will not be long before the EV revolution will be halted by the piles of dead EVs that we cannot re-cycle.

So no, I doubt I will ever buy an EV either but the way things are shaping up that will mean the end of motoring for me and many like me. Millions of us will be forced to walk, bus or cycle and doff our caps to the small number of the elite who can glide past in their fancy corporate leased TESLAs. It is the new feudalism.

My 20 year old Honda Accord has done 125k miles and should last at for around the same again if I maintain it. I bought it for £2300, 8 years ago.

With an EV, replacing every 7 years (assuming that is when the battery is starting to go) means for a 20y lifespan I would have needed 3 EV, each for a higher initial outlay.

If looking only at my 8y ownership, I’d have needed 30k to buy a new Fiat500 (but it’s just too small!). Against my 2k outlay this is just nuts.

I argue I’m way greener just by not chasing the latest model, not lusting after a new 73 plate, simply by keeping my car going.

Agreed, the same for us with our 16 year old VW Polo diesel but will we be able to keep these old cars going? If the ban on ICE car sales goes ahead, will we still be able to get spare parts for old ICE cars? Will there be garages able to repair them? Indeed, will we be allowed to keep them? will the price of petrol and diesel be pushed up to drive us off the road, will the tax, pay per mile and ULEZ schemes all be jacked up to force these cars off the road.

So yes indeed an old car kept going is greener than an EV but greener still than that is having no car at all! and in my opinion that is the intention behind this. TPTB want all us hoi-polloi forced to give up our cars altogether, they are fed up with the common man travelling all over the place, they want us back in our boxes in their 15 minute cities.

They will have to prise my keys from my cold dead hands

The aftermarket parts business is doing very well thank you! It will need to be closed down by Governments to make old cars go away. That is probably the next plan, some tried to make all spares come from the original manufacturer by law, but fortunately it didn’t work!

The other problems with renewables is the massive problem of recycling the solar panels and the turbine blades.

And making them…

Is anybody ahead of me on this, but what happens in the event of a breakdown of an EV? Given they can’t be pushed because of no gearbox, can they be towed or winched onto a truck?

I think they have to use some sort of towing dolley frame, it makes EV breakdowns much more expensive to handle. Everything about EVs is more expensive, our local garage tells me the Health and Safety insist that 2 technicians work on an EV for safety cover in the event of a fire or electrocution.

This’ll make you laugh.. the Rac and some private rescue providers send a diesel rescue van with a diesel generator in the back to charge up your toy ev car at the side of the road!!! Oh and imagine the cost for that!…..Fossil fuel ban?

Bo££o&ks!

The reason: There is no other way!

The Battery Electric Vehicle will be made to succeed until everything has collapsed around it and other people’s money has run dry. Then, and only then, will it fail.

I avoid every part of the Green Blob if I can help it. Despite being harassed every 2 weeks by my energy company insisting I should make an appointment to have a smart meter fitted, I ignore them. I could get on my high horse by calling them up and giving them a piece of mind for this harassment but my tactics are that maybe it is best not to draw attention to myself and get them on my case more than they already are. I also will never have an electric car but that is more likely because I might not be around in 20 years time anyway, rather than for all the reasons that appear in this article.—– Near where I live there is a hydrogen experiment going on (the first in the world apparently) where the road around a housing scheme in a place called Buckhaven in Fife is being dug up to enable hydrogen into those houses. Apparently, these folk have volunteered to get this hydrogen into their houses to replace their current gas central heating, with the extra incentive of a free new boiler. I read in the Herald about a month ago that the company refuses to reveal testing data as they think it may harm the viability of the project. So what do they have to hide? ——-Many readers on this site are aware of what is going on here and they are also aware it has little to do with saving planets. If anything it is the green blob people that need saved rather than the planet. But it is all well and good the like minded people on here who have read things other than IPCC reports and have long since stopped tuning into BBC Climate Advocacy on their 6 o’clock News. —The task is to expose the Green (Red) blob to the general public. This is for sure a very difficult if not virtually impossible task as the green blobs propaganda machine is a well oiled misinformation machine that has 95% of the media and 98% of UN lackey politicians on its side. They all waved Net Zero through parliament with no questions asked, despite not one of them knowing how this absurdity could ever be paid for and even if the technologies could even ever be invented. —Who in their right mind indulges in behaviour like this worse than the dumbest Lemming? —-Our squirming parasite politicians, who suck up to the UN and WEF pretend to save the planet people rather to their own citizens.

I prefer cars with internal combustion engines rather than spontaneous combustion engines.

I heard tell of someone with a top end EV in which the battery failed, despite the car being just over 2 years old. However, mileage had exceeded the warranty on the battery and the replacement cost over £15K. There’s a lesson in there somewhere…

https://electriccarguide.co.uk/the-best-electric-car-battery-warranty/

I agree with the whole article but for the record: the Fiat 500 is not the cheapest electric car.

https://www.carmagazine.co.uk/electric/cheapest-electric-car/

I do not agree with the ban of ICE cars or the rest of the Net Zero panic.

However, I have been driving an EV as my main form of transport since 2019 and it works very well for me. We are fortunate to have the space and funds to install solar PV, home battery, and EV charger. The car is quick, reliable, fun to drive, and servicing and maintenance to date has been £0. I have experienced no range anxiety, fires, or collapsing car parks. The battery has shown no noticeable degradation and has an 8 year warranty.

My concern is that eco zealots will make it harder and less convenient for the average person to own and operate a car by introducing lower speed limits, increased insurance costs, road pricing, restricted town centres, and anything else they can think of.