by Nick Macleod

Bertrand Russell wrote:

There is no nonsense so errant that it cannot be made the creed of the vast majority by adequate government action.

Eerily prescient, but it doesn’t tell us precisely how such nonsense overpowers our common sense. Why did the world stop turning in the face of a virus where the official advice for victims is to go home for a few days and wait for it to pass, while taking care to exercise only in their own gardens?

I don’t know the answer, but all too frequently, the first response to a novel threat has been to find a reason to panic – often as a result of a computer projection – and to stick with it, rejecting all evidence that undermines the doomsday thesis.

That may appear to be vaguely justified by the better-safe-than-sorry principle, but ill-considered and heavy-handed ‘no choice’ remedies generally do more harm than good. It might be better to study the history of past health scares and learn from it, rather than continuing to fall into the same old traps.

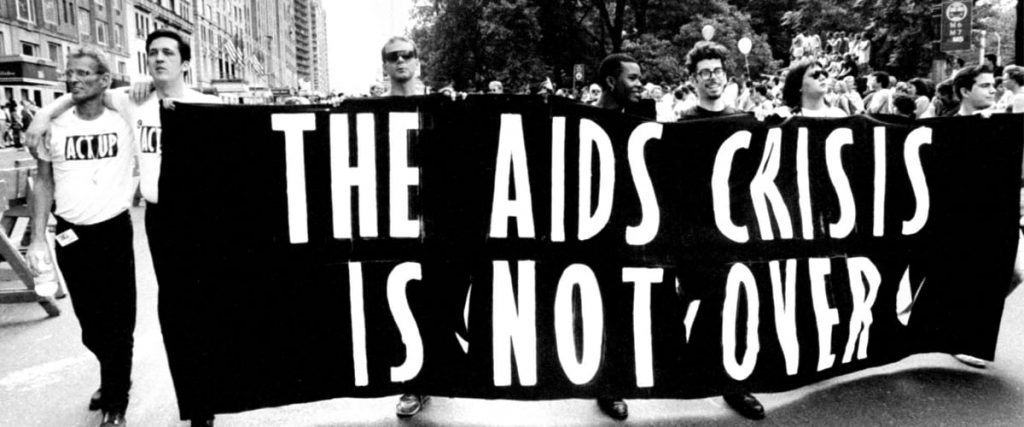

As a starting point, we might compare how early-stage forecast errors and their subsequent amplification by the media, and – more surprisingly – by the healthcare establishment itself, have manifested themselves in two particular epidemic crises: AIDS, as it emerged in the 1980s, and COVID-19 as it appears today.

AIDS and Covid are both spread by human contact, but there are important differences:

- For AIDS, contacts occur in just a few well-defined ways, so risk-avoidance strategies are available to the individual, and do not depend on the behaviour of the population as a whole.

- Specifying what we mean by a contact – and hence preventing contacts – is more difficult for Covid than it is for AIDS, and the risk of contracting Covid infection depends on other people’s behaviour as well as our own.

- People who are infected with Covid recover in significant numbers, and it is believed that at least some Recovereds will be immune from further infection. That was not true of AIDS where there were no recoveries, and no immunity to speak of.

AIDS entered the public consciousness in the mid-1980s. At that time, I was working in the USA as an actuary at a large multiline insurer. To my surprise, I was given the rather broad-brush assignment Assess the effect of AIDS on the health insurance industry in North America.

I spent the next several months developing mathematical models of the spread of infection, and applying them to official health statistics, which were provided under free subscription by the Centers for Disease Control in their Weekly Surveillance Report. And, like anyone who has worked with epidemiological models during an emerging infection, I came to understand that early-stage projections are not neutral; they have an intrinsic and marked tendency towards exaggeration of whatever threat they’re applied to.

The reason is that with any new health condition, early infections and deaths naturally occur among the most susceptible parts of the population. With AIDS, there were clearly-defined and relatively small groups of people who were at very high risk, and almost all of the early cases were among members of those groups. As the disease spread to the much larger lower-risk parts of the population, overall rates of infection and death fell significantly.

When unrepresentative infection and death rates derived from early data are projected into the far future their effects are greatly amplified, just as a rifle fired at a distant target will turn a tiny error in aim into a miss by miles. And once the projected rates have been translated into numbers of deaths for a population of millions we end up with apocalyptic forecasts that can’t help but induce panic.

Many scientists spend their careers searching for eye-catching results, and it must be extremely difficult to choose to tone down the few that do occur, especially when they apply to a novel and high-profile disease. The temptation to believe you’ve discovered a genuinely awful and important truth is a powerful one. The Royal College of Nursing certainly couldn’t resist: in 1985, they predicted that one million people in Britain would have AIDS within six years. But by 1990, the cumulative total was less than 5,000.

Misleading as it is, mistaking early-stage death and infection rates among the vulnerable for long term population-wide rates is just the beginning; there is a far more potent source of amplification waiting in the wings.

As soon as a naïve and alarming projection escapes from a scientist’s laboratory – or is rushed into print in the public interest – it’s picked up by the Press. The greater the danger it presages, the more coverage it will be given, the more frightening the terms in which it will be expressed, and the more widely and emphatically it will be reported.

Here are just two examples1 – the first one mildly amusing, the second more sinister – associated with AIDS:

- One of the early CDC risk classification groups was Haitian, because in the early months following the recognition of AIDS, there was an outbreak in Haiti. In due course, it was recognised that there was nothing about being Haitian that conferred any extra risk, so the Haitian risk classification was dropped, and the 10 Haitian cases were reassigned by combining them with the 10 cases in the Heterosexual risk group. The reclassification was explained fully and clearly on the CDC’s Weekly Surveillance Report, but the headlines in the following days’ papers bellowed “Heterosexual cases double!”. Anyone who knew that could only have had it from the Weekly Surveillance Report, so it wasn’t a case of unintentional misrepresentation, but at the same time, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a lie.

- In 1987, Oprah Winfrey opened her show by saying ”Research studies now project that one in five – listen to me, hard to believe – one in five heterosexuals could be dead of AIDS in the next three years. That’s by 1990.” When, later in the same show, she asked a health professional – a Dr. Martha Sonnenberg – whether that could possibly be true, Dr. Sonnenberg described the projection as “not unreasonable”, even though at the time fewer than 5% of the people who had AIDS were classed as heterosexual. When put on the spot, Dr. Sonnenberg was unable to connect the various numbers and reject what was obviously a preposterous contention. A programme watched by millions had claimed that one fifth of the US population – about 50 million people2 – would die from AIDS within just three years, and that claim had been nodded through by a medical expert. (Though obviously not an expert in mental arithmetic. At least, not in front of a live audience. But that’s showbiz!)

If we treat the UK and the US as essentially similar countries, this provides a neat illustration of how the media amplified the Royal College of Nursing’s already wildly exaggerated ‘scientific’ claim that 2% of the (British) population would have AIDS by 1990 into an unsupported assertion that 20% of the (U.S.) population would be dead by then.

Once reports like these appear in the media, reasoned discussion of agreed-upon facts disappears. Fear descends, hardened opinions form, ‘experts’ disagree, and it becomes almost impossible to establish a measured and rational Government policy. Threat exaggeration and amplification don’t make us safer; they eliminate the possibility of an effective and reasoned response. Where Covid has outstripped all previous health scares is in the worldwide suspension of freedom, without notice, without adequate legal review, and with hardly a whimper of resistance. The fragility and impermanence of what were once regarded as inalienable rights has astonished many people, and set a frightening precedent.

The history of health scares is littered with hysterical forecasts that were never remotely realised. In the case of Covid, some “scientific projections” have been discredited within weeks, even while the restrictions they led to were still in force. But it’s as though it never happened. Where we might have expected an acknowledgement of error accompanied by a re-evaluation of policy, there is silence. ‘Don’t look back’ seems to be the way forward.

Nick Macleod trained and worked as an actuary in the USA, but has spent most of my career building investment management systems for hedge funds in the U.K.

1 Among a great many others.

2 i.e., the equivalent of the entire population of the UK at the time.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostLatest News