Lockdown restrictions had little to no effect on the number of COVID-19 deaths, a new meta-analysis of empirical studies has found. The analysis, entitled “A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Lockdowns on COVID-19 Mortality“, written by Professor Steve H. Hanke, Professor Lars Jonung and Jonas Herby, has been published as a working paper by the prestigious Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise.

The authors screened 18,590 studies to find those eligible for inclusion, and reviewing 1,048 of them, identified 24 which met their eligibility criteria of being based on empirical data (not modelling) of mortality during the pandemic. They restricted their review to studies which assessed the impact of mandatory lockdowns i.e., non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), but not guidance or voluntary measures. Their preferred measure was excess mortality rather than Covid mortality as it overcomes issues with the definition of a Covid death, but they noted only one study looked at that variable.

The 24 eligible studies were separated into three groups – lockdown stringency studies, shelter-in-place-order (SIPO) studies, and specific non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) studies – and an analysis of each group supported the conclusion that lockdowns have had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality.

Stringency index studies found that lockdowns in Europe and the United States reduced COVID-19 mortality by just 0.2% on average, while studies of shelter-in-place (stay-at-home) orders found they only reduced Covid mortality by 2.9% on average. Studies of specific NPIs (lockdown vs no lockdown, facemasks, closing non-essential businesses, border closures, school closures, limiting gatherings) also found no broad-based evidence of noticeable effects on COVID-19 mortality. While closing non-essential businesses seems to have had some effect (reducing Covid mortality by 10.6%) – mainly related to the closure of bars and pubs – border closures, school closures and limiting gatherings reduced Covid mortality by just 0.1%, 4.4%, and actually increased it by 1.6%, respectively.

Since lockdowns have had little to no public health benefits, and given they have imposed enormous economic and social costs – reducing economic activity, raising unemployment, reducing schooling, causing political unrest, contributing to domestic violence, undermining liberal democracy – the authors conclude in no uncertain terns that “lockdown policies are ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument”.

They note this finding is in line with the World Health Organisation Writing Group, which in 2006 stated: “Reports from the 1918 influenza pandemic indicate that social-distancing measures did not stop or appear to dramatically reduce transmission… In Edmonton, Canada, isolation and quarantine were instituted; public meetings were banned; schools, churches, colleges, theaters, and other public gathering places were closed; and business hours were restricted without obvious impact on the epidemic.” And also that “forced isolation and quarantine are ineffective and impractical”.

Their findings are contrary to the forecasts in epidemiological studies such as those of Neil Ferguson and his team at Imperial College London, but they suggest this is owing to faults in the modelling. More generally, they observe that studies that claim to find an effect are invariably based on modelling or cover too short a time period to gain a full picture.

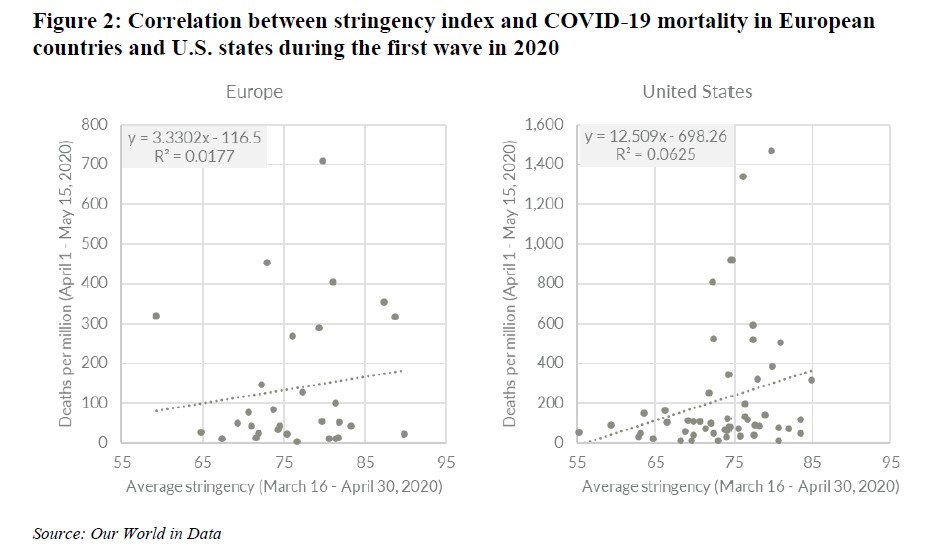

They write they were motivated to undertake their analysis in part by the striking lack of correlation between lockdown stringency and Covid mortality in the first wave. Given the large effects predicted by models such as Ferguson’s (up to 98%), they note that at least a simple negative correlation would have been expected. Instead, what correlation there was was positive – the more stringent countries and U.S. states had on average (slightly) more deaths (see chart at top). While some argue this may be because the worst affected countries responded by locking down harder, the authors point out Sebhatu and colleagues showed that Government policies are strongly driven by “the policies initiated in neighbouring countries rather than by the severity of the pandemic in their own countries”. This means it is “not the severity of the pandemic that drives the adoption of lockdowns, but rather the propensity to copy policies initiated by neighbouring countries”.

It isn’t just the raw data but several studies which find a positive correlation between lockdowns and COVID-19 mortality (meaning the strictest had more deaths). The authors suggest this counterintuitive result may be due to people being confined to their homes infecting family members, with a higher viral load causing more severe illness.

They suggest several reasons that lockdowns don’t have the effect expected by the modelling. Their main explanation is voluntary behaviour change – both in limiting contacts, so the lockdown is unnecessary, and in ignoring the mandate, so it is ineffective.

When a pandemic rages, people believe in social distancing regardless of what the Government mandates. So, we believe that Allen is right, when he concludes: “The ineffectiveness [of lockdowns] stemmed from individual changes in behaviour: either non-compliance or behavior that mimicked lockdowns.” … Herby reviews studies which distinguish between mandatory and voluntary behavioral changes. He finds that – on average – voluntary behavioral changes are 10 times as important as mandatory behavioral changes in combating COVID-19. If people voluntarily adjust their behaviour to the risk of the pandemic, closing down non-essential businesses may simply reallocate consumer visits away from ‘nonessential’ to ‘essential’ businesses, as shown by Goolsbee and Syverson, with limited impact on the total number of contacts.

They note that even with lockdowns and distancing, much contact continues – and some of the lowest mortality countries, Denmark, Finland and Norway, actually permitted the highest amount of contact in the first lockdown, allowing people to “go to work, use public transport, and meet privately at home”.

Lastly, they point once again to the counterproductive nature of some restrictions in confining people to indoor environments, noting they “find some evidence that limiting gatherings was counterproductive and increased COVID-19 mortality”.

With the empirical evidence stacked against the effectiveness of lockdowns, do you think the governments which engaged in this catastrophic error of groupthink will ever admit their mistakes, or will they forever hide behind their fanciful modelling? Maybe after an election or two, we could hope for some proper evidence-based re-appraisal.

Find the full paper here, which is of course worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.