Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began, Western commentators have spent a huge amount of time expressing moral outrage at Russia’s actions, but comparatively little time thinking about how the war could have been prevented.

This is puzzling. Even if Ukraine manages to win, this victory will have come at an enormous price – tens of thousands of lives, millions of refugees (many of whom may never return), and untold damage to the country’s infrastructure. No matter what the outcome, the war will have been disastrous for ordinary Ukrainians.

It therefore seems essential to ask whether it could have been prevented.

One possible way it could have been prevented is through deterrence. NATO members could have announced in advance, ‘We commit to defending Ukraine if it is ever attacked by Russia’. Alternatively, the U.S. and its allies could have armed Ukraine to the teeth by transferring huge quantities of offensive weapons.

The disadvantages of this approach are obvious. It might have caused Russia to invade even sooner to forestall the arrival of NATO troops or weapons. And if Russia did call the West’s bluff, it might have sparked World War III, as NATO would have pre-committed to entering the war on Ukraine’s side.

There’s another possible way the war could have been prevented: through the implementation of Minsk II. This was an agreement signed in 2015 by representatives from Russia, Ukraine and the two separatist republics, which aimed to bring an end to the fighting in Donbas. It was based on a plan drawn-up by the leaders of France and Germany.

Although Minsk II ultimately failed, since neither side honoured the terms, it was unanimously endorsed by the UN Security Council.

Critics of Minsk II say it was too favourable to the Russian/separatist side. This is because the agreement would have granted significant autonomy to the two Donbas regions, allowing them to veto Ukraine’s future membership of NATO and possibly its membership of the EU as well. (Minsk II is roughly equivalent to the plan John Mearsheimer put forward in 2014, which emphasised Ukrainian neutrality.)

For Ukrainians who aspire to fully integrate with the West, not being able to join NATO or the EU represents a major loss. Yet a significant minority of Ukrainians want to remain close to Russia, and for them fully integrating with the West represents a loss.

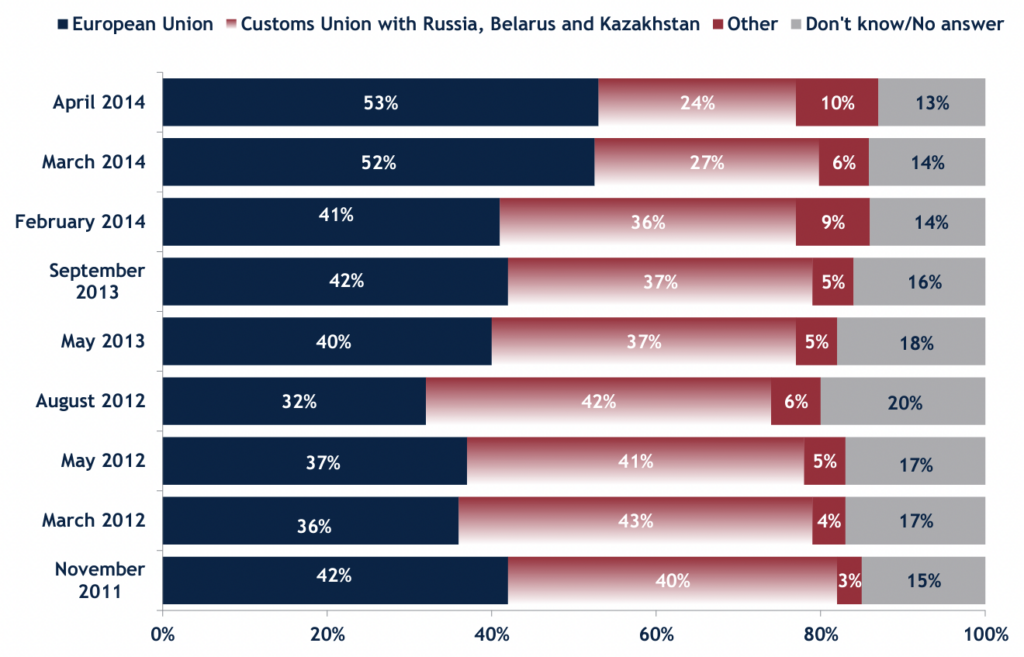

As late as February 2014, the percentage of Ukrainians who wanted to join the EU was only 5 points higher than the percentage who wanted to join the Eurasian Customs Union. The balance of opinion then shifted after the ‘Revolution of Dignity’.

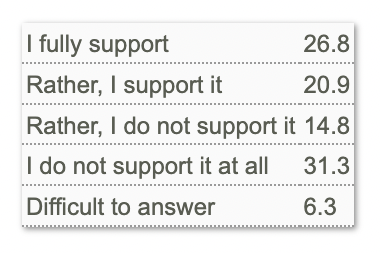

Likewise, almost half of Ukrainians opposed the Maidan protest movement, including a plurality who “[did] not support it all”. For this reason alone, calling the subsequent change of government a ‘Revolution of Dignity’ is highly dubious.

The fundamental problem for Ukraine was that a majority of citizens sought closer ties with the West, but a significant minority sought closer ties with Russia, and these two aspirations were mutually incompatible.

You might say that in a democracy, the majority gets to decide the future path of the country, so Minsk II was fundamentally unfair. Yet it’s widely understood that in ethnically divided countries, the majority often has to make concessions to the minority for the sake of overall stability. Half the parliamentary seats in Lebanon are reserved for Christians and half for Muslims, regardless of the ethnic make-up of the country (which no one quite knows), to prevent one group from dominating the other.

In any case, the European interest – as judged by the leaders of France and Germany – was preserving stability in Ukraine, rather than ensuring the country’s pro-Western majority got its way.

According to the New York Times, the plan for Minsk II emerged “in response to reports that lethal assistance was now on the table in Washington”. In other words, the U.S. wanted to start supplying Ukraine with offensive weapons, so France and Germany stepped in to broker a peace deal before that happened.

Why did Minsk II fail? As I’ve already stated, neither side upheld its end of the bargain. Yet historian Anatol Lieven argues it could have worked but for “the refusal of Ukrainian governments to implement the solution and the refusal of the United States to put pressure on them to do so”.

Lieven’s argument is consistent with numerous public statements made by Petro Poroshenko, the former Ukrainian President under whom Minsk II was signed.

In 2020, a Radio Svoboda journalist asked him whether he signed Minsk II in order to “buy time”. Poroshenko replied, “Of course”. He also said he was “categorically against” granting “special status” to the Donbas because it would lead to the “federalization of Ukraine”.

In June of this year, he told a different Radio Svoboda journalist, “We achieved what we wanted … our task was, first, to avert the threat, or at least to postpone the war – to secure eight years to restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces” (skip to 00:20:20).

He said the same thing on German TV: “What is the results of the Minsk agreement?” Poroshenko asked. “We win eight years to create army. We win eight years to restore economy. We win eight years to continue the reforms and to move to the European Union” (skip to: 00:07:20).

And just last week, he fell victim to two Russian pranksters (the same ones who pranked George Bush) and admitted, “I need this Minsk agreement for having at least four and a half years to build Ukrainian armed forces … to train Ukrainian armed forces together with NATO, to create the best armed forces in the Eastern Europe, which was built on the NATO standard” (skip to 00:05:00).

All this suggests that, even if the Russian/separatist side had taken the initiative in upholding their end of the bargain, Poroshenko never intended to implement Minsk II.

His stance was echoed by Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba in February of this year. Mere weeks before Russian tanks rolled across the border, he told a Polish newspaper, “None of Ukraine’s regions will have a right to veto the state’s decisions. That is engraved in stone!”

But why, as the country’s main backer, did the U.S. not pressure Ukraine to implement the agreement? After all, the U.S. endorsed the agreement in its capacity as a member of the UN Security Council, and the U.S. pressures its allies to do things all the time.

The obvious reason is that U.S. interests were not served by the implementation of Minsk II.

From a Western perspective, preventing the war in Ukraine would have required the French and Germans to act more decisively, or the Americans to look beyond their own interests. Unfortunately, neither of these eventualities came to pass.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Police called in over abusive reaction to council’s ‘climate lockdown’ traffic scheme”

Hallelujah.! Are the good people of Oxford and Canterbury finally waking up to what they are trying to do..? Councils should stick to bins and road sweeping instead of ‘saving the planet’

That’s cheered me up on a cold and frosty Sunday. Heartwarming in fact.

The intention is that by 2030 sales of diesel/petrol cars will be banned and so by 2045, when this scheme comes, in petrol/diesel cars will have gone however, with current technology and the current electric situation, we cannot replace all these petrol/diesel cars with electric.

This seems to be preparing us for a future when we will not own our own car, this would be a huge social change as has been recognised in the responses to these schemes. But we need to wake up to the fact that this is really a softening up process and is all about taking away our cars and our personal travel freedoms.

“This seems to be preparing us for a future when we will not own our own car,”

Actually it is pointing to a future where there will be fewer of us about.

The planet will be depopulated and only the elites will have their own vehicles. The slaves will own nothing but they WILL be happy.

I used to work in local government. I had a conversation with a senior colleague who is now a Chief Executive at a council. He told me that they had once sent out a consultation document to all of their citizens. One person had returned the survey having crossed everything out and written in red marker across the page, “JUST CUT THE F~@~ING GRASS!” He had framed it and put it on his wall as a reminder. I wish they all remembered this important comment!

Re “Generation Z too petrified of climate change to have children”:

I haven’t read the whole thing because I don’t want to fund the Telegraph, but I think the whole “having children” issue needs to be talked about. While we sceptics like to talk of various elephants in rooms, overpopulation is an elephant for the political elite. No politician will dare to mention it, for obvious reasons. But it’s clearly very much at the front of their minds, and has been for a long time. A certain royal allegedly said in 1988 “In the event that I am reincarnated, I would like to return as a deadly virus, to do something about overpopulation”. Boris Johnson (or was it Stanley?) allegedly wrote in 2007 “I cannot understand why nobody is doing anything about overpopulation”. I have seen speculation linking these comments to a genocidal agenda: this may or may not be true. I’ve seen stickers on bus stops linking the latter comment to the vaccinations.

It may be one reason why the government has been pushing the “climate change” propaganda so much: let’s persuade the masses to procreate less; after all, Aesop (who may or may not have existed) told us that persuasion is better than force. The Telegraph article may itself be a piece of spin to achieve this end.

Speaking for myself: when I was a teenager in the 90s, I wondered why anybody would want to bring children into this hostile world. Maybe whatever the government was spinning at the time worked on me: I was far more credulous then. I might easily have changed my mind since then, but the cruel way in which the government has treated us in the last three years has made me very relieved I still don’t have children, for their sake, with the dystopian future they are likely to face, and the diet of (government-manipulated) social media which can easily form their opinions. When many of us were children, one of the main things considered bad for us was television: “it will give you square eyes”. Perhaps those who spoke against it were right, but not for the reasons they said.

What to do about there being a lot of people in the world? Certainly not state-sponsored genocide. I’m also not fond of the covert coaxing which seems to be the government’s way of doing everything right now; it makes people like me resist all the more, as a matter of principle. Perhaps it’s time for governments to return to telling us blunt economic truths (if they ever did), such as “our lockdowns caused massive inflation”, instead of spinning and dancing their way around everything. I would support incentives to foster or adopt, rather than to procreate. There are lots of frightened children already out there who need safe and loving households.

The elite narrative is Malthusian – that is they view the world as a zero sum game. The reality is quite different – that birth rates self-limit when children are no longer essential to support parents, that material consumption reduces as prosperity increases, and that the earths resources have always been shown to be far greater than was supposed. So we need to encourage growth and prosperity in all its forms, and not support a miserable centrally planned and restrictive economy.

One of the worst, maddest pathologies always was “I’m afraid of babies”.

Let’s not forget, birth rates in the majority of countries are falling rapidly, world wide sperms counts have dropped by more than 40% since 1970 and now child hesitatant generations!

Something we seem to forget as a race is that nature is in control, not us!

It will find its own way to bring the balance back, infertility, and no one has to die to achieve it.

Apparently dropped quite a lot since March 2020 too.

Michael Schellenberg points out in his book ‘Apocalypse Never’ that we produce more than enough food to feed the world population. The reason people go hungry is because of problems with distribution and supply.

As in Ethiopia in the 1980s.

People with large families are already seen as borderline criminal (instead of the heroes they actually are) , and people who protest against killing children in certain public places apparebtly already are criminals.

How on earth are they keeping the ‘dead donkey’ that is the scamdemic going?

Another nail in the coffin….?

https://retractionwatch.com/2022/12/01/buzzy-lancet-long-covid-paper-under-investigation-for-data-errors/

An early and influential paper on long COVID that appeared in The Lancet has been flagged with an expression of concern while the journal investigates “data errors” brought to light by a reader.

…..the paper has been cited nearly 1,600 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science. Altmetric finds references to it in multiple documents from the World Health Organization.

According to the expression of concern, dated November 24, a reader found inconsistencies between the data in the article and a later paper describing the same cohort of patients after a year of follow-up. That discovery sparked an investigation that is still ongoing:

Worth a read, it’s quite short…..

..via Dr Claire Craig’s Twitter….Signal noticed in the young as soon as they’d started giving dose one in Israel…..

https://mobile.twitter.com/prof_freedom/status/1601670384402956288

February 2021: E-Mail from Isreali Ministry of Health to EMA asking about “Safety Signal Myocarditis in younger population

Dear All,

I hope you are all well in these difficult times. We are investigating a safety signal of myocarditis / peri-myocarditis in younger population (16-30years) following the administration of the Pfizer Covid vaccine.

We would appreciate if you could share any information on the subject from your country.

…..How many doses of the vaccine were administered to this age group?

…..How many cases of myocarditis/peri-myocarditis were reported in your country

…..Could you elaborate details on these AE cases(time of diagnosis from the vaccine, first/second dose, risk factors etc…

…..Have you assessed the causality between the AE and the vaccine for each case.

We’ll be happy to exchange data on this topic with you…..

First freaking dose…February 2021…..shocking!!

Another piece of information that would tend to show that things were ‘planned’ …?

FOIA’d Contracts Show CDC Expected up to 1,000 VAERS Reports per Day for COVID Vaccines”With up to 40% of the reports serious in nature”

https://jackanapes.substack.com/p/foiad-contracts-show-cdc-expected

This is well worth a read and is truly shocking….

This information means of course that the CDC had been told to expect 1,000 reports per day by those responsible for the “vaccines.”

As Lord Bill of the Gates of Hell has said: “we didn’t do a very good job with the vaccines.”

Supposedly he was alluding to numbers injected but of course what he was actually referring to was numbers killed and maimed.

The fact that the first ‘contract’ was from August 2020, well before vaccines were available, and well before any permission for them was granted is an absolute shocker….I’m currently in a state of so much hatred for these people…..

along with the evidence from the Twitter files..we have been mugged right royally….and I know there’s much more but….lied to, rights taken away, mandates, giant experiment, which they knew would kill and injure, job losses, baby’s jabbed…kids dead..WTF…!!

He could add a few more words to his comment, such as “,like the other products my firm developed”!

Yep.

Top bloke!

https://flvoicenews.com/desantis-florida-will-hold-covid-19-vaccine-manufacturers-accountable/

Gov. Ron DeSantis said that his administration plans to hold vaccine manufacturers accountable for making false claims about the mRNA COVID-19 products that may have caused injuries, and even death, among some who received the vaccines.

“I have Surgeon General in Florida Dr. Joseph Ladapo who’s been really, really strong of just fighting back the narrative and the phony things that people are trying to do and focus on the evidence and so we are gonna work to hold these manufacturers accountable for this mRNA because they said there was no side effects and we know that there have been a lot,” said DeSantis.

Brilliant.

A bit worrying though that he apparently doesn’t support free speech.

Thought that this might appeal to our collective warped sense of humour

Posted on Substack

Enjoy: MERRY CHRISTMAS

It snowed last night…

8:00 am: I made a snowman.

8:10 – A feminist passed by and asked me why I didn’t make a snow woman.

8:15 – So, I made a snow woman.

8:17 – My feminist neighbor complained about the snow woman’s voluptuous chest saying it objectified snow women everywhere.

8:20 – The gay couple living nearby threw a hissy fit and moaned it could have been two snow men instead.

8:22 – The transgender man..women…person asked why I didn’t just make one snow person with detachable parts.

8:25 – The vegans at the end of the lane complained about the carrot nose, as veggies are food and not to decorate snow figures with.

8:28 – I was being called a racist because the snow couple is white.

8:31 – The middle eastern gent across the road demanded the snow woman be covered up .

8:40 – The Police arrived saying someone had been offended.

8:42 – The feminist neighbor complained again that the broomstick of the snow woman needed to be removed because it depicted women in a domestic role.

8:43 – The council equality officer arrived and threatened me with eviction.

8:45 – TV news crew from BBC showed up. I was asked if I know the difference between snowmen and snow-women? I replied “Snowballs” and am now called a sexist.

9:00 – I was on the News as a suspected terrorist, racist, homophobe sensibility offender, bent on stirring up trouble during difficult weather.

9:10 – I was asked if I have any accomplices. My children were taken by social services.

9:29 – Far left protesters offended by everything marched down the street demanding for me to be arrested.

By noon it all melted

Moral:

It all happened because of snowflakes

That is ABSOLUTELY brilliant. Thanks for posting.

Hahaha! Love it. I feel that humour has become quite scarce around here of late, most people are very business-like and on-topic the whole time, so a bit of light relief is much appreciated.

Speaking of scarcity, how’ve you been, BB, as I’ve noticed you’re not on here so much anymore? We got spoiled by your regular ‘BB tsunamis’ of in-coming posts I think. Anyway, don’t be a stranger.

Anyway, don’t be a stranger.

Change of mind I hope Mogs?

I’ve sent you an email.

I messaged you, hux. My emails are now so over-run with crap I’m missing important ones. I must pull my socks up!

Thanks Mogs. I have just read the email. I am a selfish bugger at times but thanks – great news.

Thanks Mogs,

I’ve had a few challenges to deal with, but haven’t been completely absent, just quiet. Hope to be up to attending a MD4CE meeting this evening with Dr Nagase. If I manage to have enough brain to attend, will report back.

Glad you appreciated it.

BB

I much enjoy and appreciate your posts BB.

Thanks BB. He’s the Canadian doctor isn’t he, who was reporting on the nano-weirdness found in the vials as well as the >stillbirths and <birth rates I think..? Glad you’re still with us!

LOL! But you and I know this is like a true-life fecking diary…….it’s a very weird world when the ‘jokes’ are absolutely true!! Good laugh though…..

Fabulous and true!

Don’t know if people know this website showing where our energy is being generated. It’s the coldest night of the year so far and we are getting 3% of our energy from our great future energy sources. Hmmmmmm

https://grid.iamkate.com/

Wow!

Many thanks for this.

At last! I was wondering what it would take…

Elton John who has linked up with Marmite. It may be a bit marmite, but maybe best avoided now. Other yeast extracts are available.

If you have to be persuaded, reminded, bullied, pressured, incentivised, lied to, guilt tripped, coerced, socially shamed, censored, threatened, paid, punished and criminalised, if all this is necessary to gain your compliance, you can be absolutely certain that what is being promoted is not in your best interest.