The pandemic has shone a spotlight on public health ‘experts’.

Many initially opposed lockdown, before abruptly changing their view when doing so became politically convenient. They said that masks don’t work, only to turn around and back mandates. And after assuring us the vaccines would stop transmission, they were met with overwhelming data to the contrary.

In October of last year, I wrote about two studies in which ‘experts’ and laymen were asked to forecast weekly Covid numbers. ‘Experts’ performed somewhat better in the first study, but actually performed worse in the second. A possible explanation for the divergent results is that laymen in the second study were self-selected and hence better-informed about the subject matter.

These findings don’t inspire confidence in the ‘experts’ who’ve guided us through the pandemic. After all, the most basic task of science is to predict things, so if scientists can’t predict better than laymen, that suggests their theories are wrong. And if their theories are wrong, we probably shouldn’t listen to them – especially if they’re telling us to shut down the economy.

That’s public health scientists. Are social scientists any better? According to a new study: no, they’re not. (The study is still a pre-print, so hasn’t been peer reviewed.)

Cendri Hutcherson and colleagues asked both ‘experts’ and laymen to predict the size and direction of social change in the U.S. between April and October of 2020. There were ten different domains: prejudice, individualism, traditionalism, generalized trust, political polarisation, life satisfaction, depression, delay of gratification, birth rate, and attitudes to climate change.

Then in October of 2020, participants were asked to give retrospective estimates of the size and direction of social change over the preceding six months. Prospective and retrospective estimates were compared to objective indicators of social change, based on large representative surveys.

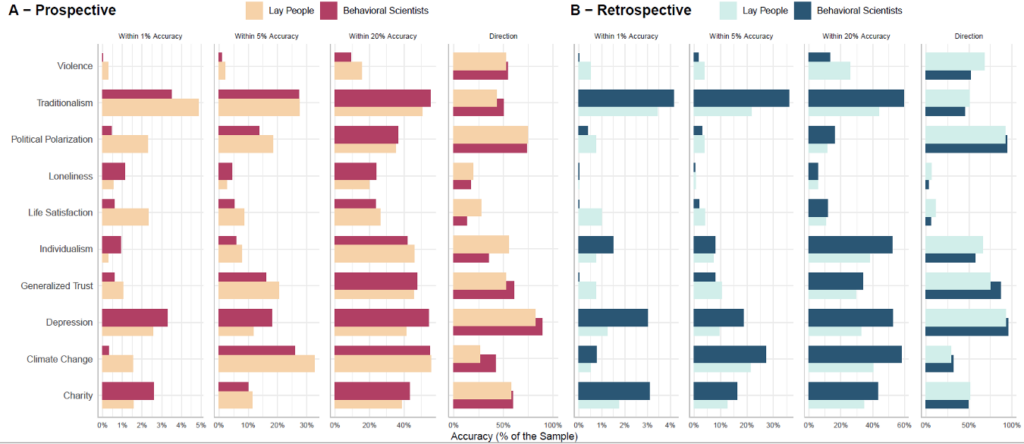

The researchers found that ‘experts’ and laymen were equally inaccurate, as shown in the image below.

Although the ‘experts’ did better in some domains, the laymen did better in others – so there was no overall advantage for the former group. Remarkably, this was true even when it came to retrospective estimates. (You might have assumed the ‘experts’ would at least do better here, since they might be familiar with the data.)

Interestingly, the researchers found in both groups that participants who expressed greater confidence in their estimates were less, not more, accurate. So beware of those who tell you something will or will not happen; the best forecasters are aware of the inherent uncertainty in human judgement.

It’s not just public health scientists who advise governments and other large institutions; its social scientists too. Hutcherson and colleagues’ findings should make us wary that such people have any more insight than the rest of us.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Soziologie ist der Mißbrauch einer zu diesem Zweck erfundenen Terminologie (Sociology is the abuse of a terminology invented for this purpose). It’s really that simple. Sociology is no more a science than theology. Both are elaborate systems built upon unverifiable stories people told.

All the Sociologists I ever met were narcissistic, naïve, malignant idiots. Without exception.

Modern day science as far as it pertains to public policy is the process of predicting but never verifying The verification part has been replaced by propagandising.

So none of the climate predictions from 15 and 20 years ago are being checked. You know, the ones where the Maldives would be under water by now and the North Pole without ice in the summer.

Instead we just have an updated set of predictions.

That’s the science.

Don’t forget “If you take the vaxx, you’re a dead end for the virus. You can’t spread it, you can’t get infected”.

“If you’re unvaccinated, you’re facing a winter of death and severe illness”

“It’s normal to get 4 shots + take a course of pills costing over 500 bucks and still get really ill – that means it’s working”.

“If you’re unvaccinated, you’re facing a winter of death and severe illness”

What idiot put that statement out?

If you’re dead you cannot thereafter suffer severe illness.

As a social experiment it failed, badly. If it had all been ignored no one would have been any the wiser, just like when they picked the ‘wrong’ flu concoction in 2017/18 and the excess deaths were in the region of 50,000

I agree…although knowing how ineffective the flu vaccine is, after much research, maybe the numbers would have been the same with the ‘right vaccine’….the flu deaths seems to go up and down regardless.

‘Modern science’ is often thought of as the application of ‘the scientific method’.

For some reason the ‘scientists’ that get the most media coverage these days appear to be the ones working in fields where their theories and guesses can’t be tested using the scientific method.

Sociology, climate change, economics, etc etc.

There’s also vaccine development, but that’s only because they choose not to use the scientific method to rigorously test their products, not because the scientific method can’t be applied.

Susan Michie is a “scientist.”

Apparently.

Communist theoreticians usually call (or called) themselves scientists. For Mitchie, that would be behavioural materialism, the belief that people’s minds work mechanically/ mindlessly by always producing a predictable reflex to the right kind of stimulus. There’s a reason why she believes that other people talking is – for all practical purposes – identical to dogs crapping on the streets: It’s some function of ftheir body they perform instinctively whose only purpose is the emission of some physical byproducts which are unpleasant and more-or-less dangerous.

For practical purposes, a sizable body of so-called contemporary science can be defined as Something with math and computers. That’s really nothing more than bullshitting people by telling them complicated-looking stuff they don’t understand. Goethe once wrote the verse Oft glaubt der Mensch/ Wenn er nur Worte hört/ Es müsse sich dabei/ Doch auch was denken lassen (People usually believe that what was said must have had a meaning). That’s from the so-called witches’ scene from Faust I and refers to the witches’ chants which are really just a gibberish of syllables and don’t mean anything. That’s exactly how this science

works.

This was very evident during the Corona heyday, when press statements supposed to justify another round of measures or another delay before relieving them would frequently be justified by some expert enumerating a lot of common knowledge, eg, about how respiratory diseases work out or how the immune system attacks pathogens and pointing out that there was so far no proof that it would also apply to The Terrifying New Virus[tm]. This was then usually followed by a long string of We don’t know this, we don’t know that, here’s something else we also don’t know and this one we don’t know either, all expressed in very learned sounding and vaguely fear introducing words to camouflage that this so-called expert apparently lacked any expert knowledge about the situation.

Well observed.

I remember years ago reading about most traders performing no better than a computer randomly picking stocks. I don’t know if that’s still the case but imagine it probably is.

In every profession there are a few genuine experts, the rest are just doing a job.

I know plenty of people who know more about their job than I do but in no way do I consider them smarter than I am and I’m not saying I’m particularly smart.

The way I judge expertise is whether or not their knowledge is time gained or true understanding, i.e. would I, or a regular person be at that level if we’d spent as much time doing the same job. Often I find the the scope of knowledge is limited and they can’t answer basic questions about their subject of expertise. It’s even possible to spot the ones who’s exams were primarily multiple choice because the way they come across is very formulaic and you can almost guess what their response will be before they try to answer a question.

The social ‘sciences’ are just the humanities in unconvincing scientific drag. I should know. I work in a branch of them.

“Expert” – an ex is a has been and a spurt is a drip under pressure

Genuine empirical science can only be concerned with the purely material universe whose components – atoms, molecules, gravity, sound waves etc – act in a regular therefore predictable manner.

Human beings possess free will (another way of saying a soul) therefore their thoughts, attitudes and behaviour are unpredictable.

In other words all ‘human science’ – psychology, sociology, economics, anthropology, Marxism etc – is pseudo-science.

These faux sciences not only constantly get there assumptions and facts wrong, but are intrinsically harmful due to their dehumanising effects.

As a glance at the history books (including the very recent one of lockdowns etc) shows.

Beyond Vitamin D: Why You Need Regular Sun Exposure

https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2022/07/31/what-you-need-to-know-about-melatonin.aspx

What You Need to Know About Melatonin

Analysis by Dr. Joseph Mercola

**

Yellow Boards By The Road BUILD BACK FREEDOM

**

Thursday 4th August 11am to 12pm

Yellow Boards

Junction A321 Wargrave Road &

A4 New Bath Road

Twyford RG10 9PN

**

Stand in the Park Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am – make friends & keep sane

**

Wokingham

Howard Palmer Gardens Sturges Rd RG40 2HD

**

Bracknell

South Hill Park, Rear Lawn, RG12 7PA

**

Telegram http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell