They say 13 is unlucky for some – well, it looks like that’s true for anyone wanting to investigate the impact of the Covid vaccines on infections, hospitalisations and deaths as, true to its word, this week, week 13, sees the last Vaccine Surveillance Report issued by the UKHSA to include these data.

From April 1st 2022, the U.K. Government will no longer provide free universal COVID-19 testing for the general public in England, as set out in the plan for living with COVID-19. Such changes in testing policies affect the ability to robustly monitor COVID-19 cases by vaccination status, therefore, from the week 14 report onwards this section of the report will no longer be published. Updates to vaccine effectiveness data will continue to be published elsewhere in this report.

The point about testing is somewhat valid, of course – the problem is that this change won’t affect hospitalisations and deaths data, and they could replace at least some of the infections data with the results that come from the (continued) testing of healthcare workers. This comes at a time with record-breaking infection levels in the U.K., as identified by sources including the ONS and the Zoe Symptom Tracker. These record case levels have been reported in the media, such as in the Guardian and the BBC; I find it odd that these reports blame the virus and our relaxation of restrictions for the record case levels – they don’t even mention the possibility that it is the vaccines that are causing this problem. Twelve months ago there were plenty of experts suggesting that mass vaccination could result in what had been seen in prior candidate vaccines for coronaviruses – an initial few months of protection followed by an increase in susceptibility to disease – but the existence of these warnings continues to be ignored. On the other hand, the promises that these vaccines were ‘safe and effective’ continue to be believed, despite vast amounts of evidence suggesting the opposite (they’ve certainly not worked to get us to ‘Zero Covid’).

To be fair to the UKHSA, there is likely to be a huge impact from the removal of free testing (which has cost the U.K. extraordinary sums of money for little apparent benefit) on infection statistics, and Covid appears to have mutated into a much more benign virus. As things stand, there is hardly more benefit to the population in informing them of Covid case numbers as there would be in informing them of the number of colds going around at the moment. Nevertheless, the data had been useful in terms of identifying the actual value of vaccination (also costing extraordinary sums of money for what now appears to be little apparent benefit). I can only imagine that the decision to stop publishing infections, hospitalisations and deaths by vaccination status has been made, as in Scotland, to reduce the risk of inconvenient facts being released (note that UKHSA promises that it’ll continue to release convenient facts).

Enough moaning about what was inevitable – on with the analysis of this week’s data.

Cases

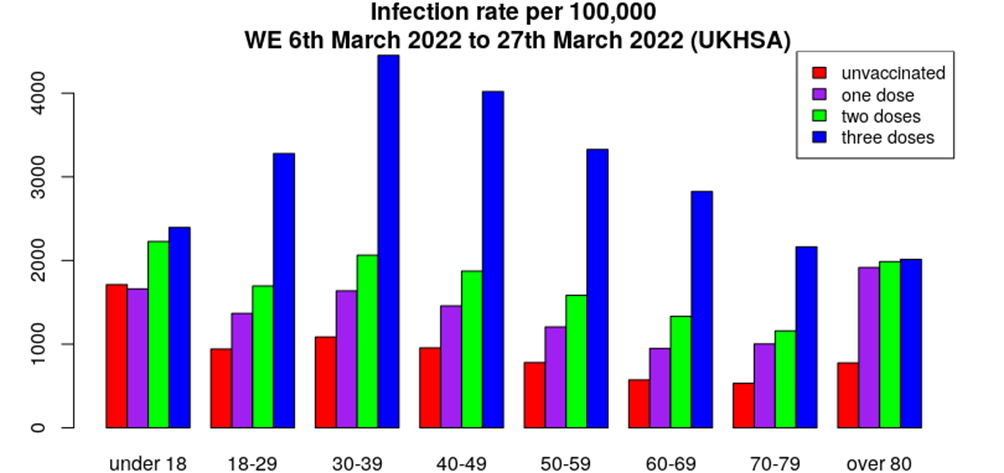

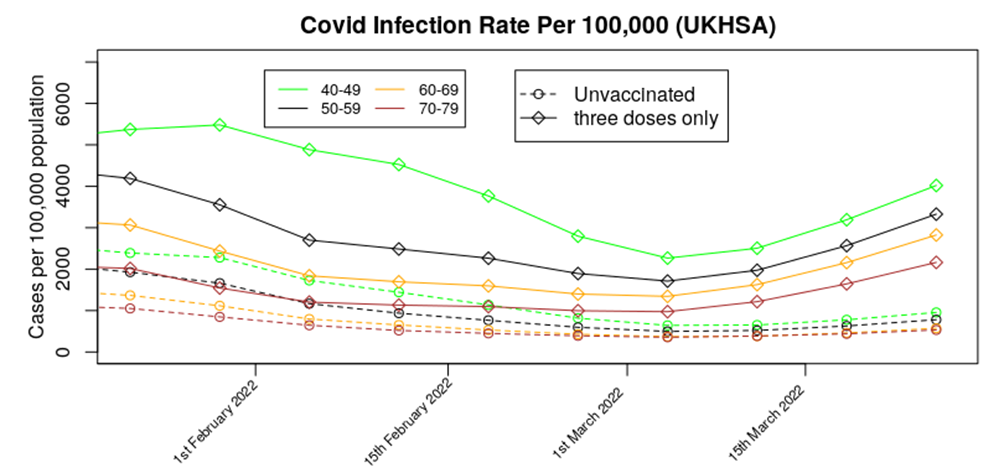

While the UKHSA data haven’t quite matched the data from the ONS and Zoe Symptom Tracker since the start of the year, they are currently making up for lost time in showing a substantial increase in cases compared with last week’s report. Once again, the report shows most new cases to be in the triple vaccinated, with the unvaccinated showing the lowest numbers of new infections.

The progression of the current Covid wave by vaccination status is fascinating – the new infections appear to be occurring disproportionately in the triple vaccinated with only relatively small increases in those that have received fewer doses and the unvaccinated.

This said, the huge discrepancies in rate of increase seen in earlier weeks are no longer seen, with this week’s data showing an increase in case rates in those aged 18 to 80 of around 22% for the unvaccinated, the single dosed and the double dosed, and a 28% increase in the triple vaccinated – though the large discrepancies in overall case rates remain, of course.

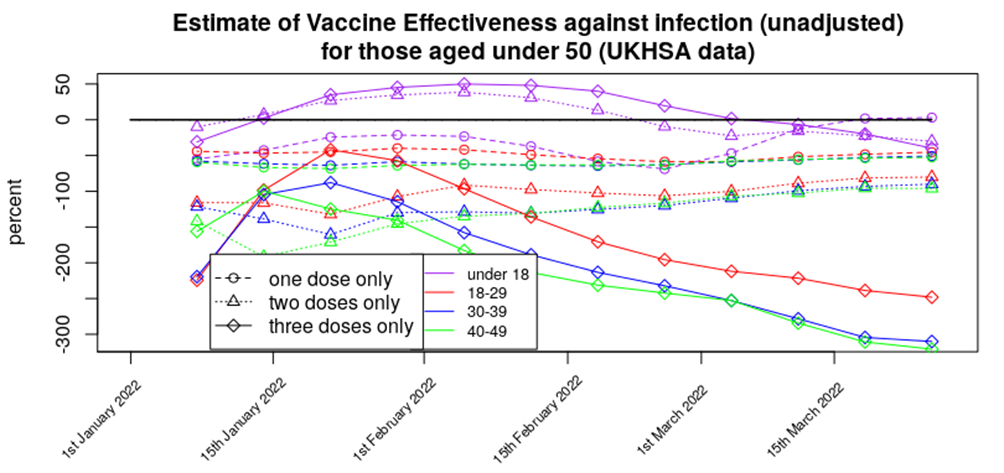

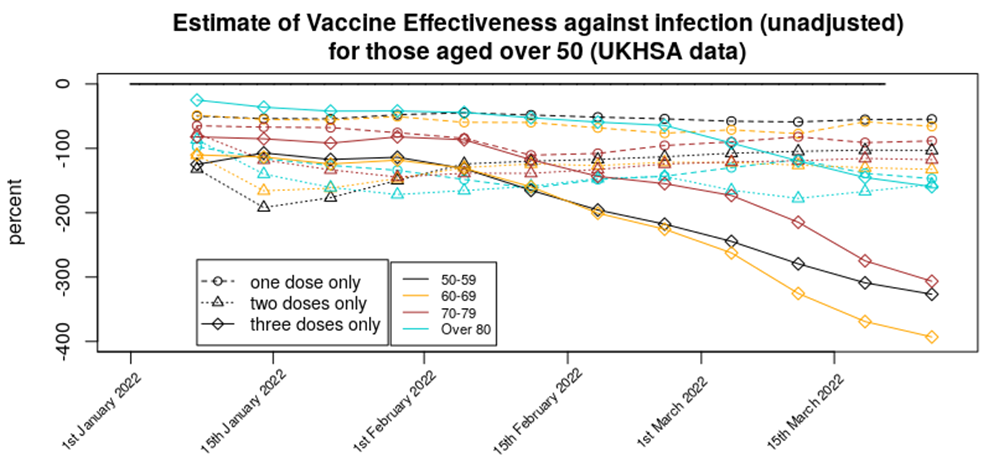

These new data are naturally reflected in our estimates of the vaccines’ effectiveness at preventing infection, with data for one and two doses of vaccine remaining broadly static (albeit negative) and new lows in our estimates of VE for the triple jabbed, with those in their 60s hitting almost minus-400%, meaning the triple jabbed are around five times as likely to test positive as the unvaccinated. Note also that our estimate of VE for the triple jabbed aged under 18 has now firmly cemented its position below zero.

Hospitalisations

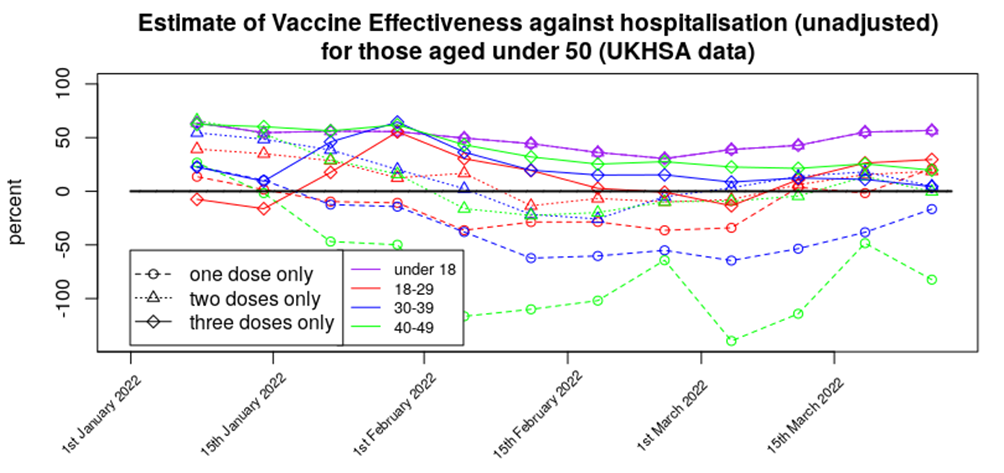

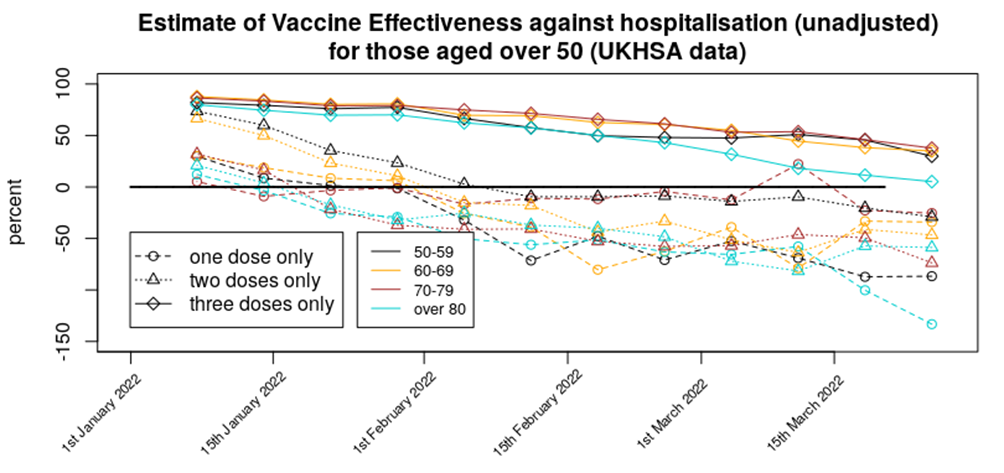

The UKHSA data on hospitalisations show a similar trend to last week’s data – three doses of vaccine show some protective effect, whereas the protective effect for those having been given only one or two doses remains close to zero. Again, the data show a slight uptrend in the estimated VE for younger individuals. As mentioned in last week’s post, this is somewhat expected based on trends seen in previous waves; it is unfortunate that we’ll have no further data to explore this effect.

Of specific note this week is the move towards zero of the estimated VE for protection against hospitalisation in those aged over 80 – this is the very age group for which the vaccines supposedly offer real benefit (as they’re at most risk from Covid); the data suggest that the vaccines have failed in this role.

Deaths

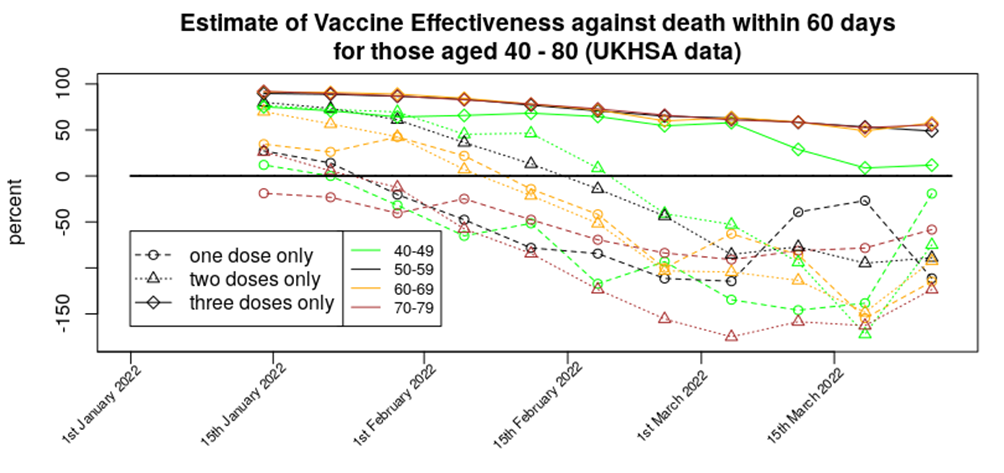

The estimates of vaccine effectiveness at protecting against death continue to show the same trend – an apparent protective effect of the third dose, but that one or two doses end up increasing risk.

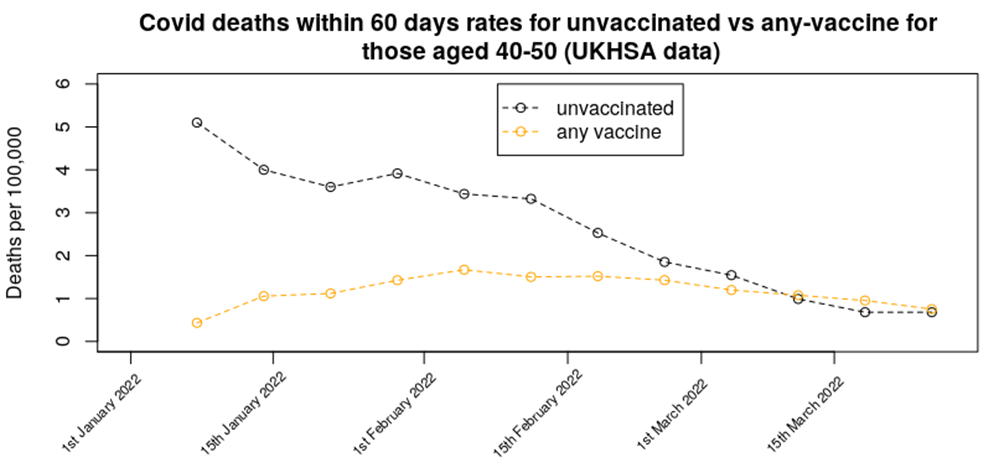

Caution is required for these data as there is evidence that the apparent protection against death for Omicron variant is much more complicated than it appears – I have hypothesised previously that this has occurred because those closest to death have not been offered the latest vaccine dose. This effect is apparent when the mortality data is analysed by the unvaccinated versus those that have been vaccinated with any dose as one group.

This week shows a reversion to the trend in the 40-50 age group, and a similar result in seen for all those aged under 50 – the vaccines appear to offer no protection against death for the individuals that have lower vulnerabilty to Covid anyway.

And so the days of the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report’s section on infections, hospitalisations and deaths by vaccine status draw to a close. As I mentioned earlier, the ending of the publication of these data was inevitable – indeed, I’m only surprised that it lasted this long. Perhaps we need to thank those people in the UKHSA that continued to publish these data even when they started to diverge from the official narrative. As to the future? I suppose we’ll have to content ourselves with the data crumbs that do get published.

I’ll close with some thoughts on where things might go from here and what signs to look out for.

Infections: It is highly likely that we’re currently reaching the peak of the current Covid wave in the U.K. The big question is where it goes from here – what is most likely is that it will drop to a new intermediate level and remain elevated for some four to six weeks and perhaps longer. The higher this intermediate level is, the worse the long term outlook because of what it tells us about the role of the vaccines in suppressing immunity and driving infections; I’d imagine that a levelling off at over 50,000 cases per day would be a negative sign. Once we get to the end of spring it is most likely that we’ll see a substantial drop in cases due to seasonality – but if cases don’t drop to near zero by June then it doesn’t bode well for the future.

Hospitalisations: With the Omicron variant we have probably got close to the point where there is no meaningful protection against hospitalisation offered by the vaccines (both because the virus has evolved to become less pathogenic, and because vaccine effectiveness is very much reduced). What happens next is unclear. The infections data suggest that the Omicron variant has evolved to meet the immune characteristics of the majority of the world’s population (i.e., vaccinated people that have antibodies against one very specific spike protein) and the immune characteristics of the unvaccinated are no longer relevant to its existence, whether they’ve had a prior infection or not. At the same time, our immune systems are complex and we don’t fully understand the impact of different subtypes of antibodies declining (waning) at different speeds. With this in mind, I’d suggest that we look out for people falling ill very rapidly without the classical period of symptomatic Covid, and possibly with some time (weeks) between infection and the onset of Covid disease complications, as this may reflect the vaccines inducing tolerance towards the virus.

Deaths: Omicron appears to be much less lethal than prior Covid variants, although note that it appears to have brought with it a longer period between initial infection and death (in both vaccinated and unvaccinated). I expect to see official figures continue to show low death rates from (or with) Covid over the coming weeks and months, but with the complication that the real death rate will likely be somewhere between two and three times greater than official figures show (deaths within 28 days of infection). Now that we’re entering spring the death rate will almost certainly plunge and the real test will probably come next winter – but that’s a long time off and we’re probably best advised to enjoy our summer instead of worrying about it.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

NZi gov can call a multilateral peace and reconciliation conference.

Hey presto: it’s called DEMOCRACY.

ONLY once jacida is stripped on rank, pension and everything but pre-taxpayer employment wealth and goes to live in exile (she is a globalist after all and thus hates her home country).should they chat about peace.

Have family in New Zealand and weep for them. Like around the world so many have been brainwashed and supportive of these evil entities. I’m an agnostic, but boy do I hope there’s a God. Getting through the Pearly Gates is not going to happen for them. Scrooges chain will be nothing compared to Ardern’s and Trudeau’s etc. Vallance increasingly going up the list.

“There are no atheists in foxholes.”

good one

“ONLY once jacida is stripped”

Hold it right there.

I don’t want to see her stripped, that would be going too far.

Fifty upticks!

TCW poll – Can the Canadian truckers hold their nerve?

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/tcw-poll-can-the-canadian-truckers-hold-their-nerve/

Kathy Gyngell

Don’t get complacent. Let’s keep getting the message out with our friendly resistance.

Tuesday 15th February 2pm to 3pm

Yellow Boards By the Road

A321 – 141 Yorktown Rd,

(by Sandhurst Memorial Park Car Park)

Sandhurst GU47 9BN

Stand in the Park Sundays 10am make friends, ignore the madness & keep sane

Wokingham Howard Palmer Gardens Cockpit Path car park Sturges Rd RG40 2HD

Henley Mills Meadows (at the bandstand) Henley-on-Thames RG9 1DS

Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

I was saying only yesterday to a friend, this is why they need to remove the Canadian truckers before they can roll back any restrictions. They are playing a very dangerous game of chicken with peoples lives, to save face. Doesn’t that perfectly sum up the last 2 years…

NO – they need to remove Trudeau from office – he is a stooge of the WEF and unfit to govern a democratic country. The damage he had already done to Canada is incalculable.

Absolutely. Hold the line.

Referring to some protesters as “the anti lockdown crowd” is both insensitive and dismissive. The protesters certainly do have “skin in the game,” they are fighting for freedom and humanity.

I believe a more supportive and decorous tone would have been a better match for such an historical event.

Totally. My brother is over there and his anxiety levels are sky high. He is losing his job, his wife will likely lose hers (she succumbed to the pressure and had one dose, but was so ill she won’t have another) The kids are excluded from everything. It is beyond shit. Those criminals in the NZ government need to face the full force of retribution for what they are doing.

Bloody hell Sophie; what’s happening to your family really hurts.

FWIW, all the best.

That’s dreadful, Sophie.

Has your brother sought the help of Voices For Freedom? They’ve got lots of supporters and plenty of advice. Perhaps then he won’t feel so alone.

Look at their website: voicesforfreedom.co.nz

I am so sorry for your family. Are there any means whereby they can deprive Ardern of her power. Is there a mass movement like in Canada? I’m not usually an advocate of revolution, but NZ needs to do something drastic, surely?

Difficult to think straight when you’re drunk on power, wearing your self-righteous face and floundering around in a sea of money and “connections”. Being anointed a “Young Leader” by WEF & Co. doesn’t make you one. It turns you into a full time skivvy, instead of just an amateur one.

So a self-righteous face is a cadaverous one with lots of prominent teeth.

The NZ government like the French, Austrian and Australian varieties amongst others, which are controlled by the Globalists, cannot really make any concrete decisions until they consult with their masters such as Gates and the central bankers who are pulling the strings!

Exactly.

It’s not Gates, and is most-likely not anything to do with banking. The bankers profit most from relative stability, and Gates is too shallow and immature to run with the likes of Ayers and Soros.

I will admit that both Gates and “Th’ Jooz” are very attractive for Conspiracy Theorists. Carry on with it, if you like.

So all the money Gates is documented to have pumped into media around the world, to cover health matters, has no bearing on the way in which mainstream media reports on the vaccines?

That does have a bearing, but it’s a relative late-comer, and Gates hasn’t ever shown the underhanded cojones which Soros has. Gates throws money around, but there are others who are far more dangerous.

As food for thought, have you ever heard of something called “JournoList”?

Soros and Gates are all members of the World Economic Forum.

Yes, both of these individuals are front men for the bigger fish that own and control most of major corporations in the World. Before slinging slime and smear, have a look who owns the Vanguard group !

Where was the ”slime and smear”? It sounded like just an opinion to me.

if you read his original comment to me, you would see what I was driving at !

Gates ‘owns’ the WHO and backed the Tedros appointment …did you know that?

And apparently Lockstep isn’t happening and Billy Boy is not working with Ayers and Soros.

pBMb needs to have a long re-think.

I agree that Bill Gates is probably NOT hand-in-hand with Bill Ayers and George Soros.

Gates doesn’t pack the gear to run with that crowd.

Back in his Weather Underground days, Ayers co-wrote a revolutionist manifesto named Prairie Fire. In it, he said 25 million Americans would have to die, and that the USA and Canada would eventually be divided up by Russia and the Bolivarian revolutionaries to our south.

http://www.zombietime.com/prairie_fire/

The closest Gates ever came to doing something like that was DOS.

For clarification the comment on Ayers and Soros was intended as sarcasm

Gates, Soros, Schwab, Carney and the rest of the Davos Deviants are all working to the same script.

“ It’s not Gates” ? Really !

” Nor anything to do with banking “ Who owns the Federal Reserve in the US ?

” ..Conspiracy Theorists” Now, which organisation first brought this expression into the public arena so vividly?

https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Melinda_Gates

A trivial (perhaps not-so-trivial) rejoinder —

On that webpage, notice the quote about vaccines. It’s positioned so people will think it has to do with COVID. In reality, the statement is from 2010, before the fake COVID “vaccines” were invented.

Yes, who does own the Fed? … Say it, loud and clear. C’mon.

Perhaps if you read the article in more depth, you might have noticed the cosy relationship they have with current heads of some Western governments.

Hmm, as I posed the question, the normal response to it is either

A. You know and state who they are.

B. You don’t know who they are.

So which is it ?

Let’s see Gates visits Bojo and many of the Western puppets who listen to his every word as though it was sacrosanct .He gives $1000,000s to Imperial College London, MHRA plus many institutions around the world and to many of the unelected advisors in SAGE, Fauci etc who advise / tell the governments what the latest policy is.

The Federal Reserve is owned by whom?

A. The US government.

B. A group of central banks.

The Bank of International Settlements, the central bankers bank, which through its members oversee the monetary policy of almost every country on Earth.

Moreover many of the members in many governments around the world, such as the U.K. have been through the revolving system of central banks.

“ ..Conspiracy Theorists “ which nefarious Organisation first brought this term so vividly into the public realm ?

I will give you a clue it concerned the fate of a man who saved the world from Armageddon!

Cute

Not Gates? Gates is at the centre of the vaccine offensive on the world as any interview with him over the last decade reveals to anyone bothered to check it out!

RFKJ’s detailed and full referenced book on Fauci reveals his meetings and planning with Gates over twenty years.

You need to do a bit of reading and catch up!

No-body talks any longer of “Conspiracy Theories” by the way, just blatant easily researched and documented conspiracies.

See my video, which I made for those who are about twenty years behind the learning curve.

https://www.bitchute.com/video/Ckt0Rv0DAMyY/

You appear to be confusing ‘nice cuddly’ High/Main Street bankers and the feral Central Bankers behind institutions such as the IMF which are intended to load victim countries up with so much debt enabling them to be bled dry.

Read John Perkins’ Confessions of an Economic Hit Man for the full inside story.

BTW Lukashenko of Belarus was offered a $1 billion IMF ‘loan’ to go along with the lockdown scam. He refused, so the next stage was the coup to replace him with a pliant WEF protege. That also failed thanks to a heads-up from Russia. Debriefing some of the participants also revealed the end game was to kill him. This all fits in with Perkins’ details on the IMF strategy – bribe, replace, eliminate

Trudea and Arden need to go, these monsters, tyrants covered in the blood of the innocent for their own advancement, may they never sleep soundly until they beg for forgiveness

Why should they ever “sleep soundly?”

Call for a vote of no confidence in it’s self. Those that vote Aye, get to keep their seat at the election.

Those that vote ‘Aye,’ get to STAND at the next election.

Bob Morans take in todays CW.

Is this Paris NZ or Canada?

Just a snapshot of universal Globalist Law ‘n Order policy – isn’t “World Government” going to be just wonderful !

Abbie Hoffman, Chicago, 1968: “The first duty of a revolutionist is to get away with it.”

Do you assume I’m writing that about the protesters? … Hell no.

Anyone who thinks there’s absolutely no sort of great reset at work in the panic-demic should seriously consider pulling head from nether orifice.

Occam’s Razor strongly suggests that the Down Under inanities and those in the UK and North America are – in some meaningful fashion – linked.

The governments are struggling mightily to “get away with it”.

Exactly what the linkage/s is/are is an open question, the relative sameness in governmental actions are too obvious to ignore.

The revolution was not televised because they ran the TV stations!

We have to undo their revolution as it’s our slavery they were fighting for..

Which revolution are you referring to? The DNC in ’68, or some other, more recent?

That ’68 revolution was won by the “McGovern Democrats” taking control of the Party over the next 12 years. There are no more “Scoop Jackson Democrats”. They defected to the GOP during the Reagan years, and were kicked out by Trump in 2016.

Italy’s Archbishop Carlos Maria Vigano Endorses the Canadian Truck Drivers Against the New World Order (VIDEO and Transcript)

https://www.thegatewaypundit.com/2022/02/italys-archbishop-carlos-maria-vigano-endorses-canadian-truck-drivers-video-transcript/

Your protest, dear Canadian truck driver friends, joins a worldwide chorus that wants to oppose the establishment of the New World Order on the rubble of nation states, through the Great Reset desired by the World Economic Forum and by the United Nations under the name of Agenda 2030. And we know that many heads of government have participated in Klaus Schwab’s School for Young Leaders – the so-called Global Leaders for Tomorrow – beginning with Justin Trudeau and Emmanuel Macron, Jacinta Ardern and Boris Johnson, and before that Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy and Tony Blair.

It would seem that Canada is – along with Australia, Italy, Austria and France – one of the nations most infiltrated by the globalists. And in this infernal project we must not only consider the psycho-pandemic farce, but also the attack on traditions and Christian identity – indeed, more precisely the Catholic identity – of these countries.

You understood this instinctively, and your yearning for freedom was shown in all its coordinated harmony, moving towards the capital Ottawa. Dear truck drivers, you are facing great difficulties, not only because you give up your work to demonstrate, but also because of the adverse weather conditions, long nights in the cold, and attempts to be cleared away that you face. But along with these difficulties you have also experienced the closeness of many of your fellow citizens, who like you have understood the looming threat and want to support you in protesting against the regime. Allow me also to express to you my support and my spiritual closeness, to which I join the prayer that your event may be crowned with success and may also extend to other countries.

In these days we see the masks of tyrants from all over the world fall, and unfortunately we also see so much conformism, so much fearfulness, so much cowardice in people who up until yesterday we regarded as friends, even among our family members. Yet, precisely because of this extreme situation, we discover with amazement gestures of humanity made by strangers, signs of solidarity and brotherhood on the part of those who feel close to us in the common battle. We discover so much generosity and so much desire to shake us from this stupor. We discover that we are no longer willing to passively suffer the destruction of our world imposed by a cabal of unscrupulous criminals, thirsty for power and money.

In this relentless attack on the traditional world, not only your way of life and your identity have been affected, but also your possessions, your activities, and your work. This is the Great Reset, this is the future promised by slogans like Build Back Better, this is the future of billions of people being controlled in their every move, in all their transactions, in every purchase, every bureaucratic practice, every activity. Automatons without souls or wills, deprived of their identity, reduced to having a universal income that allows them to survive, to buy only what others have already decided to put up for sale, transformed by a gene serum into people who are chronically ill.

Today more than ever it is essential that you realize that it is no longer possible to passively assist: it is necessary to take a position, to fight for freedom, to demand respect for natural freedoms. But even more, dear Canadian brothers, it is necessary to understand that this dystopia serves to establish the dictatorship of the New World Order and totally erase every trace of Our Lord Jesus Christ from society, from history, and from the traditions of peoples.

Demonstrate for your rights, Canadian friends: but may these rights not be limited to a simple claim to the freedom to enter supermarkets or not to be vaccinated: may it also be a proud and courageous claim to your sacrosanct right to be free men. But your demonstration should be one of true freedom, reminding you that it is the Truth – that is, Our Lord Jesus Christ – who alone can guarantee you freedom: the truth will make you free.

Let us pray that Christ will return to reign in society, in your hearts and in your families. Take up the spiritual weapon of the Holy Rosary, and pray to the Blessed Virgin, Sainte Ann, Saint George and the Holy Canadian Martyrs to protect your homeland.

I would like to conclude my appeal by asking you to pray with me, with the words that Our Lord has taught us: may they be the seal of this awakening, of this national liberation. Let us all pray it together, out loud, so that our prayer may rise to Heaven, but also so that it may resound powerfully in these squares, in these streets, all the way to the palaces of the powerful:

+ Carlo Maria Viganò, Archbishop

Archbishop Vigano is the greatest of our senior clergy and for those not supporting him – Pope – hang your heads in shame.

Macron currently has around 25% support in the French polls. His four opponents share 57% of voter support, The three right of centre candidates share 47% support and yet Macron with total Media and Globalist support expects to be ‘re-elected’ as President in the two-stage French voting system.

There lies the problem.

I wager $20 that half the commenters on this blog don’t know who Bill Gates and Bernadine Dohrn are. Don’t know what they did. Have never seen the magazine cover photo of Gates standing theatrically on something, captioned “Guilty as hell, free as a bird”. Don’t know of a attempted robbery of a Brinks armored car on Long Island, and the role Dohrn had in preparing for it.

Awww, what th’ hay! That’s history stuff! Yeah, who cares! Out with the Old, in with the NEW! WHEEEE!

This is primarily a UK oriented website.

Gates is global 99% of readers here know of him, plenty know he hides his moobs under.strange jerseys & may be linked.with flights to a certain Caribbean island.

The Weather Underground is a Murkan thang, there are more people who will have heard of Baafer Meinhof than the Weather underground.

I know all of that.

What Ayers did back in the 60s isn’t really what matters. It’s what he’s been doing for the past 30 years, and he prays (metaphorically) that you don’t know about it.

You are saying, I gather, because Gates is widely-known, he’s all that matters.

Might it occur that I may be trying to get across some things which are important to research, to learn about, and to make your own decisions regarding?

No im not saying that, just read what I said without making stuff up.

If you come out of the rabbithole, you will find Gates is known of worldwide, reported on & given publicity, which rather negates your first point that most of the readers of this blog don’t know who Bill Gates is.

You’re saying I gather that the Weather Underground was active in Europe, which I think is mistaken, it was a Murkan thing.

Might it occur to you that the Baader Meinhof lot were of far more note in Europe at the time, even though they were not active in the UK, they were reported on widely & there were links to PIRA

I wager another $20, that only about 1 out of 20 on this blog know of Dohrn’s comment regarding one of the Manson Family stabbing a lunch fork into Sharon Tate’s dead (and formerly pregnant) belly. What did she say and how did she act in saying it?

That only 1 of 30 know who raised Chesa Boudin, the present DA of San Francisco, and know what Boudin was doing back in 2009. Where was it, and for who? And what did Boudin know about an ‘export trade’ which his employer had developed, designed to … quote … ‘inundate’ the US with a particular ‘substance?

The most Bill Gates ever did was throw after-work pool-parties where his early Microsoft crowd used drugs and swam naked with … um, ah, er … uh … y’know … who were ’employed’ for the ‘occasion’.

Certainly demonstrates the long march through the institutions.

No, what’s needed is a public exorcism of Jacinda, so people can glimpse the evil claws tugging at the puppet strings.

Email recently from Nature, formerly a Science magazine/high-impact factor publisher

quote:Hello Nature readers,

Today we learn that heart-disease risk soars after COVID — even with a mild case….

….Even a mild case of COVID-19 can increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular problems for at least a year after diagnosis, show data from the United States. Researchers found that rates of many conditions, such as heart failure and stroke, were substantially higher in people who had recovered from COVID-19 than in similar people who hadn’t had the disease. “It doesn’t matter if you are young or old, it doesn’t matter if you smoked, or you didn’t,” says study co-author Ziyad Al-Aly:unquote

nary a mention of the jabs

Let me see if I’m getting the right idea (not the mistaken misinformation stuff): the “unvaccinated” should get jabbed as quickly as possible so that they don’t suffer heart problems (because the vaccines stop you from getting COVID).

And here’s the beauty part: you could have had COVID without knowing it! Ergo, all heart problems, for the time being, are caused by COVID.

They are something else.

Are they still flattening the curve in New Zealand?

It seems that the most extreme Davos Pupils of Schwab, Macron, Trudeau and Ardern are showing their real Fascist faces and what their ‘Great Reset’ power grab project really means for the people they seek to enslave – shocking scenes from Paris, NZ and Canada as peaceful unarmed protesters are assaulted beaten and injured by ‘Robo Cops’, Body Armoured, Police thugs – Macron even ordered “maximum violence” with military grade armoured cars on the streets of Paris – as he deployed a new Urban Warfare squad to assault the people ( car windows smashed by police , gun drawn and pointed at motorist- caught on video)!

Tourists including children were tear gassed in bars along the Champs Elysée.

How much longer will this “scamdemic” tyranny be allowed to wreck people’s lives across the world in pursuit of the WEF/ UN/ Billionaire agenda?

Not much longer. They are about to fall. Big time.

They could try saying sorry, we were told it was a deadly virus……

Lets hope that this is the case. As I said earlier, the country I was born in – the UKSSR – is now a hostile nest of weaponised nefarious tech which is mainly being designed in Israel – by our “Friends” – and made in China. I dont think of this place as home or a free country any more, its a technocratic Communist grey soulless police state Freemasonic shithole run by the worst people in history, populated by their brainwashed braindead victims. It didnt used to be like this it used to be a cool country in the 90s with at least some REAL FREEDOM which has been destroyed by the tresonous scum in the government and the police. I am sick to my stomach of having to endure living in a place which has all this weaponised crap – lights and microwave towers and food and now the “medicine” they provide for their engineered scamdemic exercises – bioweapon rollouts all of which is based on them being nothing but criminal scum. The people are now weaponised bags of hijacked genetically modified Frankenstein cells thanks to these scumbags for crying out loud – spike protein and graphene shedding bioweapons full of nanotech. I dont want to shake hands or be near vaxxd people at all thanks to these scumbags. I only go to public places as this is the only access to internet I have and I feel this info needs to get out because everyone keeps stupidly putting their faith in these void of conscience proven criminals to run their world in the face of all the evidence which has been compiled and packaged for them, they still believe in obvious lies. I realised how braindead Brits truly are when they swallowed the clearly fake 911 narrative with buildings turning to dust in seconds etc. How could people be so unbelievably dumb, I kept asking myself. Its just about everyone in the UK.These agents of evil in HMG and all the scum poncing money from the public purse and whatever these greedy vile people decide they deserve have simply destroyed everything that makes life worth living. I avoid going to all cities and drive certain routes to avoid all the microwave weapons they have installed EVERYWHERE. A roads and Motorways are total no go zones – the M6 for example is hell on earth, a dystopian road which was conceived in Satans sphincter. You go in the shops and they all have weaponised microwave crap on the ceilings to compliment their thug scumbag security staff and all their braindead Orwellian workers muzzled and jabbed – plus of course all the imposing nefarious surveillance cameras EVERYWHERE making the whole place feel like it was designed by the military, not city planners or people who have any comprehension of how special the world is. Just military tech everywhere and “DEAL WITH IT” screamed at you by the disciples of this evil if you dare to complain. The schools are all choc a bloc with these weapons – in places like France and Israel they dont routinely expose their kids to this crap because they respect what it does. Brit morons live on this crap. I couldnt live in a property near any other people because I dont want their weaponised SMART meters and wifi irradiating me while I sleep. Its like living in an electromagnetic war zone. I dont want pieces of excrement scum criminals with no morals designing the world I live in. Keep your shitty technology to yourselves, kill your own family with it if you want to use it and f*** off out of our government. Same to the treasonous scum in our governments who are signing all this crap off. Their day of being exposed for the deceitful robbing criminal filth that they are is coming and it cant come soon enough.

All maimed and murdered by these scumbags and their bioweapon to “save lives”:

Athlete’s HEARTS FAILING – Documented Timeline MARCH 2021 – JANUARY 2022

https://www.bitchute.com/video/53eCIUCeKYwr/

There was yet another “medical emergency” in the crowd during a premier league football match today.

For the second time in months, in the Newcastle United crowd, medics had to rush to save someone who’d collapsed.

Previously they’d tell us what had happened afterwards and if the person survived, but it’s all hush now that it’s becoming a regular occurrence.

good

Have family in New Zealand and weep for them. Like around the world so many have been brainwashed and supportive of these evil entities. I’m an agnostic, but boy do I hope there’s a God. Getting through the Pearly Gates is not going to happen for them. Scrooges chain will be nothing compared to Ardern’s and Trudeau’s etc. Vallance increasingly going up the list.

Yes, the political situation needs an exit, that of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and all her henchmen. She obviously has no concept of individual freedom and democracy, but is a WEF despot of the highest order.

What it should do and what it will do are very different.

It SHOULD scrap the Covid restrictions and mandates and restore freedom. But Gates/Fauci/Big Pharma and the WEF wouldn’t like that – and that’s who they are working for.

I am in NZ and drove part of the way in the convoy. This article does not capture the sheer magnitude of this protest action, which has supporters in every corner. The convoys themselves – several as coming from different directions (& there has also been a second wave) – stretched for up to 100kms – every overbridge and small town and village was packed to the gills with young and old waving flags, signs, cheering & handing our food and refreshments. Those not in Wellington are protesting in their towns and cities. So much has been donated to those on the front lines in Wellington they have had to put out a call – no more donations please! I get the sense the supporters are in the high hundreds of thousands (NZ has a population of 5mil)if not in the millions. The more infantile and violent the government forces are, the more lies & disrespect by politicians (all of them – we do not have 1 politician in NZ who has stood against all things harmful in the Covid response) – its been astonishing and heartening to see how it has magnitised the protest movement for any & all who have wondered whether any of the Covid response makes any sense.

There are some good personal accounts in some of our alternative press eg https://thebfd.co.nz/2022/02/14/the-govt-have-misread-this/

TVM for the local update. Good luck!

It’s definitely not about public health now, is it?

The genius behind the handling of the NZ protests deserves his moment of fame.

“The Right Honorable Trevor Mallard”

Is he the same species as Daffy Duckford?

That photo of a police”man” with his hands on that young person’s head just shows what they’re up against. I hope he can be identified. The poor training and gratuitous violence is disgusting.

Reading of how loud music and sprinklers were used to discomfit the protesters – and considering what they’re protesting about – why weren’t they warned over the loudspeakers of the deadly disease that was stalking them, and how they’d all die if they didn’t follow the ‘covid’ protocols?

But it’s not about a mild viral disease or public health any more, is it?

This is what happens when all the worlds Police get sent to Israel for training to learn how to dehumanise their fellow man and treat their own population in the way the IDF and Israeli police treat the Palestinians.

Amazing that violent protests were started in response to police assaulting a known criminal, yet a peaceful protester is similarly assaulted and not a word against it in the press or on social media.

The weakness of Ardern, Trudeau and Morrison is that they are in essence, despots with a penchant for totalitarianism, and therefore have to use increasingly desperate and tyrannical means to control the proles they profess, hypocritically , to care for

Hi from NZ, the arrogance of our ruling class is surely on display to the world now. The authorities are all smoke and mirrors as they continue to stir the cauldron of division in the country. Ardern, dropping her customary emotive persona, has tried to paint protestors as fringe anti vaxxers and the media have dismayed and mocked the protestors as a discordant bunch containing right wing racists. Typically, the opposition parties are silent on the subject and are hiding from endorsing the protests as well, not surprising since they have supported every single mandate in lock step with the ruling Labour party shambles. However, many of the protestors are Maori and Pacifica and tino rangatiratanga flags proliferate. ALL are united against the mandates. The authorities claim that1 since over 90 percent of people are vaxxed, these protestors do not represent NZ. They forget to mention it was only about 60 percent vaxxed before they started bullying, firing people who weren’t vaxxed, and banning people from a normal life unless they complied. And stoking the flames of anxiety and fear in order to get people to comply. Lots of people I know who are vaxxed still support the protest. Hundreds lined the roads supporting the freedom convoy when they converged on the capital. I hope all ends well, although the tune of those who rule by decree have tin ears and will probably, once they declare Covid endemic, claim victory because of their ‘policies’ and sit down to write the official “history”, even before the trampled grass in front of parliament has re-grown.