Findings reported by ecologists are hugely influential in policy debates over agriculture, pollution, climate change, conservation and biodiversity. But can we trust them? A recent paper suggests that some scepticism is in order.

Kaitlin Kimmel and colleagues set out to examine the prevalence of “questionable research practices” in the field of ecology. QRPs, as they are known, include things like not making your data and code available for other researchers to check. They also include more subtle things like selectively reporting results, tweaking the analysis until you get a significant result (‘p-hacking’) and forming hypotheses after the results are known (‘HARKing’).

It is not only researchers who engage in QRPs. Journal editors often reject papers with null or weak findings because they believe such findings will be less impactful and less interesting to readers. This leads to an ‘exaggeration bias’, whereby the average effect size appears larger than it really is because null or weak findings are not represented in the published literature.

For example, suppose 10 studies are done, five of which find weak effects and five of which find strong effects. If only the latter five end up getting published, the published literature will exaggerate the effect size in question. Such variability in results is common when sample sizes are small (when studies are ‘under-powered’, to use the technical jargon).

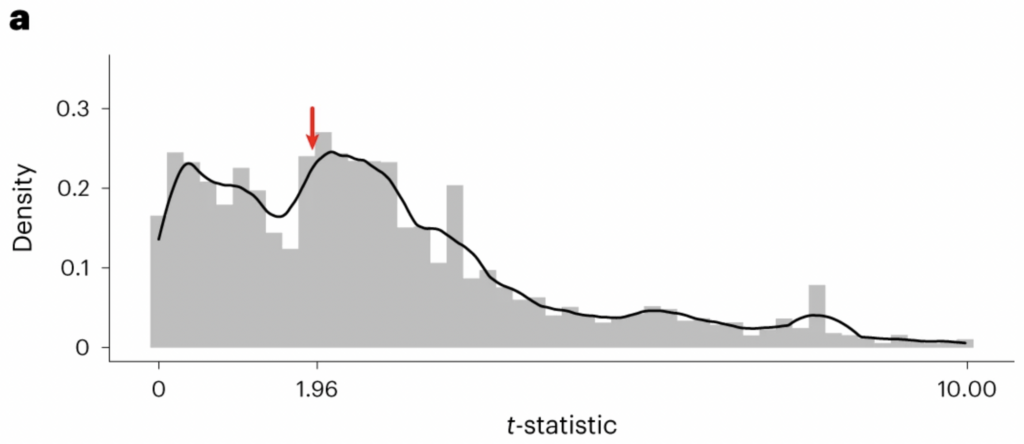

Kimmel and colleagues obtained relevant statistics from 354 articles that were published in five top ecology journals between 2018 and 2020. In one part of their analysis, they looked at the distribution of t-statistics reported by the articles in their sample. The t-statistic is something you calculate, which tells you how likely your results would be under the assumption of no effect. If it is large, that indicates your results would be unlikely under this assumption and hence that there probably is an effect.

What’s important is that, by convention, t-statistics greater than 1.96 are deemed significant whereas those below 1.96 are deemed non-significant. So if researchers were selectively reporting their results, you’d expect to see a discontinuity in the distribution, with fewer than expected just below 1.96 and more than expected just above 1.96. And this is just what Kimmel and colleagues found!

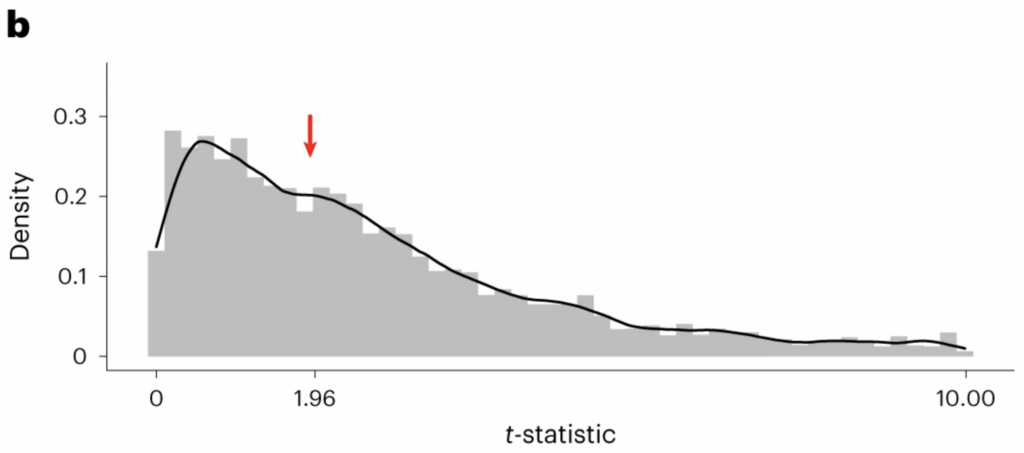

As you can see, there’s a dip in the distribution just below 1.96 and spike just above it. Which can only be explained by some combination of HARKing, p-hacking and selective reporting of results. In fact, Kimmel and colleagues found additional evidence for selective reporting. When they examined the distribution of t-statistics from articles’ appendices, there was no discontinuity around 1.96 – as shown below.

Which means that researchers were accurately reporting results in their appendices but selectively reporting results in their main texts. (This make sense, given that articles are typically be judged on the basis of their main findings, rather than any supplementary results.)

Kimmel and colleagues also found evidence for exaggeration bias in the ecology literature. In addition, they found that although data were available for 80% of the articles in their sample, code was available for less than 20%. Which means that the vast majority of articles’ results could not be reproduced without rewriting the code from scratch.

“The published effect sizes in ecology journals,” the authors write, “exaggerate the importance of the ecological relationships that they aim to quantify”. This, in turn, “hinders the ability of empirical ecology to reliably contribute to science, policy, and management”.

The paper doesn’t identify which specific “ecological relationships” are most exaggerated, nor which areas of the field are most affected, but it does offer general grounds for scepticism. Keep this in mind the next time you’re reading the science section.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

It depends what you mean by trust. As long as it’s not binary, but on a variable scale I’d say ‘yes, but…’ It appears that scientific techniques are in use, but as with many things, they tend to be selective with the truth. Often for reasons that are not declared openly.

The science of It’s above 1.96! is exactly as trustworthy as the science of immaculate conception: It happened because God willed it!

We can trust the -ology, but not the -ologists.

The -ologists reliant on funding from Government or vested interests should not be trusted at all. They have clear incentives to confirm what their paymasters say, and to refute evidence from challengers. This is the recipe for corruption, dishonesty and scientific fraud.

The jobs and promotion of junior members of the scientific hierarchy are dependent on those at the top of their profession, so do nothing to rock the boat.

All Government funding of science should be stopped – the fundamental scientific advances were made without Government funding, and in many cases by individuals who had had no formal education or university education.

So-called experts and scientific advisory bodies should be dismissed. They too will only support the policy their paymasters promote.

It’s an obvious comment but IMO worth repeating. You have to trust things and people otherwise life gets impossible. You can trust with confidence almost without thinking if either or both of the following are true (1) the consequences of your trust being misplaced are trivial and/or (2) past experience tells you that trusting this thing or person is safe. Otherwise, if the consequences to you are not trivial, trust nothing and no-one until you’ve looked into it. Always ask “cui bono?”, look at the evidence provided, and what counter arguments there are.

There is an important lesson from this old adage.—-“never buy medicine from the same doctor that diagnosed your malady”

by convention, t-statistics greater than 1.96 are deemed significant whereas those below 1.96 are deemed non-significant.

And 1.96 was revealed as magical significance number by which deity? If something indicates […] that that there probably is an effect, this means something didn’t help us gaining actual intelligence about this hypothetical effect. We may just believe in it if we so desire.

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/my-14-year-fight-for-the-cruelly-mistreated-sub-postmasters/

Andrew Bridgen has written a superb article for TCW detailing the Horizon scandal. Parliament comes out of this with zero credit and Call me Dave is as guilty as Vennells.

“I spoke to all the major media outlets. I briefed journalists at the BBC, Sky News, Channel 4 and ITV as well as all the national newspapers that I had all the proof that the Horizon scandal was the biggest miscarriage of justice in UK history. Journalists were keen and excited, but none were allowed by their editors or executives above them to run the story.

That it’s been left to ITV to mine it for dramatic purposes – presumably with the aim of turning a profit – using the wrecked lives that its editors and journalists deliberately ignored for years, I find particularly foul. Some of these sub-postmasters killed themselves.”

Thanks for the link.

The really bad thing about this is that there certainly many more cases of Computer said no! events affecting all kinds of other innocent people all the time in all areas where they’re forced to interact with automated systems.

Absolutely. 👍

As is always the case “Who pays the piper calls the tune”. —–It really is as crude as that. Let’s imagine some environmental study is done all funded by the coal industry that comes to the conclusion that climate change is not a serious problem. Straight away we know what would happen. There would be spitting fury from all manner of politicians and climate activists (who are often the same people) that this study was a disgrace and was simply the coal industry trying to protect their profits and that they had an agenda. ——-But what makes people think government do not have an agenda, and let’s remember that it is government who fund almost all climate change “science”? ——–That agenda is the UN Sustainable Development Goals. If global warming isn’t a problem then the excuses for this political agenda evaporate. So in order to control the worlds wealth and resources and virtually all aspects of people’s life which Sustainable Development tries to do, there needs to be a climate emergency and all of the so called “science” or “official science that declares this crisis is almost entirely paid for by government. ——-So coal is bad but government is good????? ——As far as I am concerned a lump of coal has done more for humanity than any squiming eco socialist politician ever did..

97% of climate & ecological scientists would be unemployed if there was no climate or ecological crisis. “Follow the Money”, seems to have more relevance today than ever.