Corroborated by three different ways of analysing U.K. population statistics (the official version, five-year and 10-year pre-Covid fatality percentage rates by month), two conclusions and one potentially relevant observation, become apparent.

First, the official Covid death toll (230,000) was overestimated by more than a factor of 2x (adjusted for dry tinder effects, the true figure was likely 95-105,000).

Second, Brits have continued to die at the same accelerated rate as during the first two years of Covid. There have been roughly 80,000 cumulative excess deaths in the 18 months since end-February 2022 (‘excess’ depends on the baseline used), but only 15,000 or so can be realistically attributed to Covid, leaving some 65,000 unexplained excess deaths (~7% of total annual fatalities).

The observation is that February 2022 was the date by when virtually the whole U.K. population had already been vaccinated, not once but twice (119 million vaccinations in a population of 67 million).

If multiple (> 2) vaccines have been suppressing, instead of enhancing, the natural T-cell immunity response, as some doctors are now arguing, it is a matter of utmost concern that there have now been 32 million additional ‘booster’ shots administered in the U.K. since this unknown killer first became apparent in the data.

New unknown killer

Former Blackrock executive Ed Dowd has highlighted that cardiovascular deaths in the 15-44 age group in England and Wales in 2021 and 2022 were not only on a steeply rising trend, but that the +40% jump (from eight per 100,000 in 2019 to 11 per 100,00 in 2022) is statistically alarming, to say the least. Yet the U.K. Office of National Statistics (ONS) points out that the U.K. age-standardised mortality rate in July 2023 was below the July five-year average (although the ONS does exclude 2020, 60% of Covid deaths occurred after that date). For the first time since June 2021, the leading cause of death was ischaemic heart disease (as opposed to dementia). However, the rate was 12% lower than the five-year average. So, does the U.K. have a mortality problem here or not?

Data inadequacy

The biggest issue we have is that the data are shockingly inadequate. Following Covid, the five-year averages have become abnormally volatile, even with the 2020 data excluded. After a material spike in mortality due to the pandemic, you would naturally expect deaths to be lower than trend, potentially disguising the sorts of new developments that Dowd claims to have identified. Covid era data was clearly unfit for purpose (unless that purpose was to deceive, discombobulate and control).

Cases & tests

For example, there was no adjustment or acknowledgement that ‘cases’ were not the same as infections (diagnoses) and were anyway clearly a function of the number of tests, which ranged from less than 10,000 per day at the height of the first wave, to 340,000 per day at the peak of Wave Two in January 2021, all the way up to 540,000 per day over Christmas 2022, before having now fallen back below 10,000 per day again since March 2023.

Hospitalisations

Hospitalisations are no better, because the data doesn’t measure patients hospitalised with suspected Covid, but rather patients within a week of hospitalisation that had, either before or since, contracted Covid. Since the main hot beds (excuse the pun) of Covid infection were the hospitals themselves (which also managed to have 10 times the case fatality rate of the wider community), hospitalisation data alone tell us very little.

The official death toll

Meanwhile, deaths data were muddied by being defined as ‘with’ Covid, rather than ‘from’ Covid which, combined with being a notifiable disease running rife through the hospitals, all but guaranteed it nightly headlines on the BBC. To date, the Covid death toll has officially reached 230,000, or 0.34% of the U.K. population. Prior to Covid, the annual U.K. death toll averaged about 0.898% of the population a year, equivalent to ~600,000 of the current population. Yet, since 2020, that annual death rate has risen +9.5% to 0.983%, but how much of this increase is due to Covid?

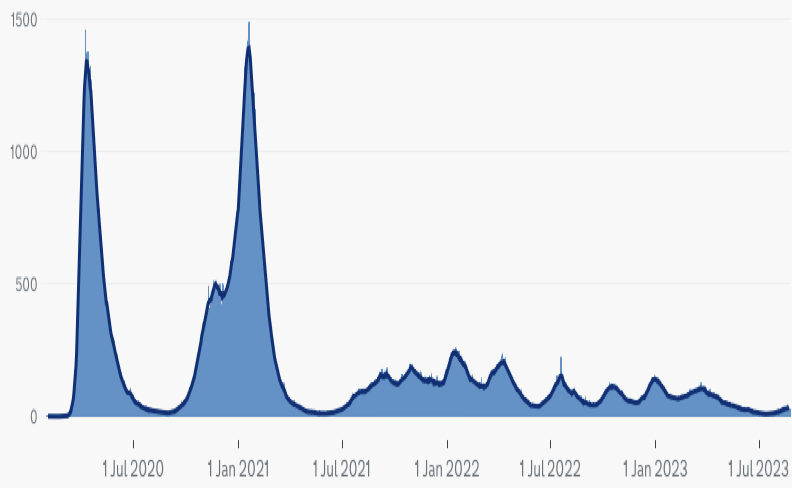

Disquiet about the reliability of data on tests, ‘cases’ and hospitalisations aside, according to the U.K. Government data on deaths, which are (only a little) harder to fudge, there were two main waves of Covid (see Chart One below), prior to winter 2021, when the disease went endemic. Officially at least, Wave One, which ran from March-June 2020, claimed 56,000 lives. Shockingly, Wave Two (October 2020 to March 2021), which might have been two separate waves overlapping with each other, took closer to 94,000 souls in just six months. Then, after ~150,000 deaths in Year One, the death toll eased back substantially in Year Two (July 2021-June 2022) to ~50,000.

Chart One: Daily U.K. deaths with COVID-19 on the certificate

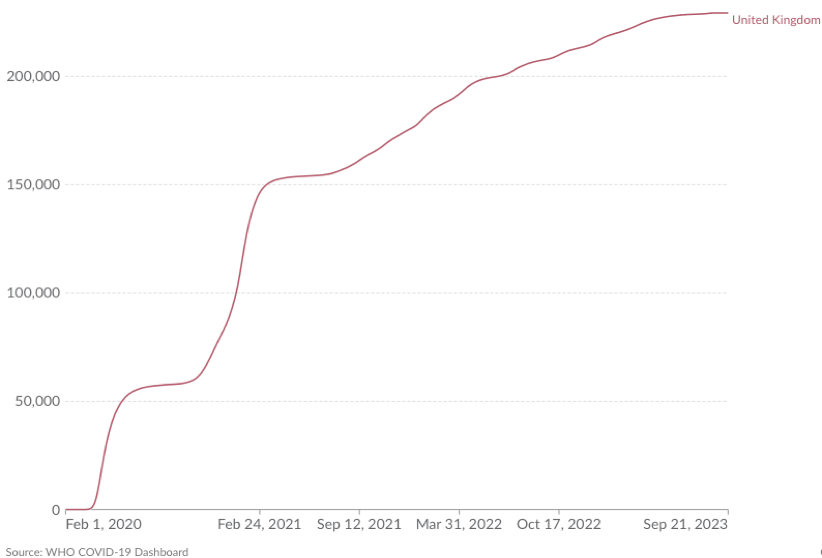

U.K. Government figures show that since June 2022 (pandemic Year Three) the U.K. annual mortality rate has moderated still further to ~25,000 (see Chart Two below). At least, that is the official story. A terrible pandemic, gradually brought to heel by a fast-acting, determined and brave bureaucracy, albeit one that denied personal freedoms whilst brooking no dissension, nor even dialogue. However, whether you wholly subscribe to this narrative or not, it seems certain a more robust calculation of excess mortality might better illuminate what sometimes comes across as an almost intentionally opaque picture.

Chart Two: U.K. cumulative Covid deaths now equal 230,115 (September 28th, 2023)

Excess deaths

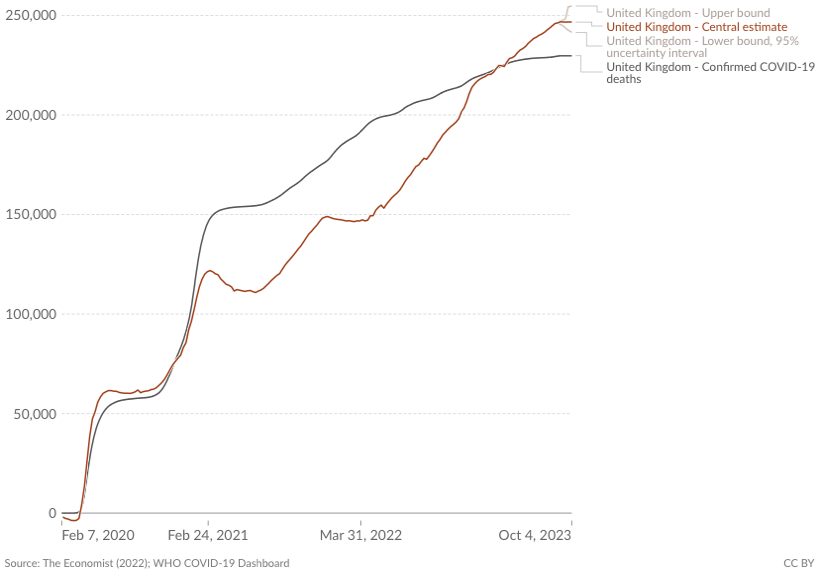

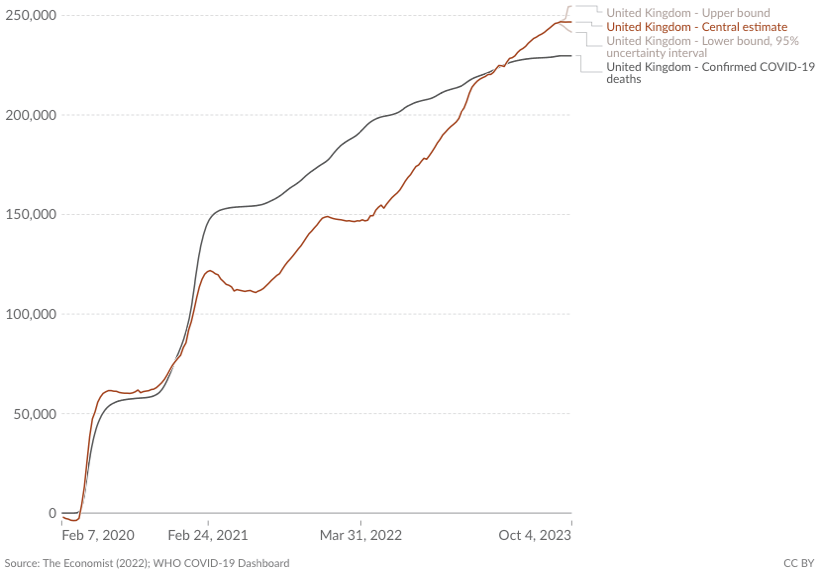

The issue is starkly revealed when we compare Covid deaths, which should all be ‘excess’, with the actual excess deaths data, which should all be Covid. However, after 2020 (Year One), this is not the case at all. Initially (Year Two; March 2021 to February 2022 inclusive), deaths officially tagged as ‘Covid’ by the authorities (see black line on Chart Three below), far outstripped excess deaths. 2021 was the year of ‘Project Fear’ when, although the threat was diminishing, the excessive use of testing, and the very low polymerase chain reaction (PCR) threshold required to determine a positive case, led to a massive overestimation of both the disease’s prevalence and its associated fatalities. From having been in line with each other as late as January 2021, by the end of pandemic Year Two (end-February 2022), cumulative Covid deaths (187,557) were officially ~41,000 higher than cumulative excess deaths (146,886). Furthermore, almost all this overstatement had occurred during Year Two.

Chart Three: Estimated U.K. excess deaths during COVID-19

A new threat

Covid deaths coming in materially above excess deaths in Year Two merely meant we were overestimating Covid fatalities. However, something much more worrying has been taking place since end-Year Two of the pandemic. Instead of excess deaths coming in below Covid deaths, as we would expect, the opposite has been happening; and at considerable scale. Since April 18th 2022 to end-August 2023, there have officially been 34,350 Covid deaths in the U.K. (official Covid deaths are ‘with’ not ‘from’ and have tended to be chronically overestimated by almost a factor of two since testing began in earnest after Year One). Yet officially, excess deaths are almost 100,000.

Something unidentified, but clearly not Covid, seems to have killed upwards of 65,000 Brits over the last 18 months; and at a monthly rate (~4,000) wholly in line with the severity of Covid itself.

A deeper dive

The above figures come from charts available from Our World in Data and demand closer investigation, especially since taking deviations from the rolling five-year average, as the ONS does, is not a good idea after a pandemic; whilst then arbitrarily ignoring 40% of that same pandemic is hardly the most robust strategy either. We can get a more detailed analysis by looking at monthly deaths in England and Wales for the five years pre-Covid (2015-19 inclusive), and dividing these by the estimated total population, to derive a monthly expected percentage death rate. This ranges from a low of 0.067% in August/September to a high of 0.0965% in January, when the elderly are at their most vulnerable to the cold weather, chronic lack of vitamin D and the stressor of annual flu. These monthly expected percentage mortality rates for England and Wales can then be scaled up and compared to the actual U.K. monthly death data from 2020 onwards to estimate excess deaths. This methodology merely confirms the story above, whilst painting a very different picture to the one espoused by the official narrative.

Pandemic Year One, Wave One

The first wave of Covid to hit the U.K., albeit mercifully brief, was shocking in its intensity (the official 34,000 U.K. excess deaths in April 2020 alone were three times higher than any month before or since, though excess deaths were over 48,000). Lasting barely two and a half months, from end-March 2020 to early June, Wave One officially claimed 57,000 lives. This tallies closely with the gross excess deaths number over the same period of 61,000. Sadly, a large number of these Wave One deaths were in the old-aged, hospitalised cohort, who were packed off back to the care homes to free up hospital beds which, ironically, were never needed. Many of those who then died in the care homes were not officially recognized as Covid deaths. Testing too had yet to be rolled out into the wider community, including care homes, so by end-June only six million (2.8%) out of an eventual 213 million tests had been done. Of these, 5%, or 285,000 cases, mainly hospital patients and staff, were positive, of which 21% died. By end-2021 in contrast, rampant testing, set to low positive PCR thresholds, was turning up 180,000 ‘cases’ a day, causing the case fatality rate (CFR) to plummet from 21% to below 0.08%, roughly the same as the flu (see Chart Three below).

Chart Three: U.K. COVID-19 case fatality rate (CFR, %)

Dry tinder

Nevertheless, in the run up to Wave One, there had been substantially fewer deaths (i.e., negative excess deaths) thanks to warmer winters and a benign couple of back-to-back flu seasons, particularly compared to the winters of 2014-15 and 2017-18. There is ample evidence of a significant U.K. ‘dry tinder’ effect built up over these prior two years (2018-20) during which, in the absence of bad flu outbreaks, there were ~21,000 fewer cumulative deaths than might otherwise have been expected. Adjusted for this ‘dry tinder’ effect, net Covid deaths in Wave One (i.e., those we can assume were due specifically to Covid rather than just extreme fragility) were much lower than the headline figure and marginally above 40,000: still awful, but nevertheless 30% less than the official Wave One Covid death figure of 57,000.

Year One, Wave Two/Three

Waves Two and Three, which started in September 2020, when Brits brought the Spanish variant back from their summer vacations before packing their kids back off to school to spread it amongst their friends, subsequently morphed into a secondary ‘Alpha’ winter wave originating from Kent which, between them, lasted until the end of February 2021. Owing to both the reportedly very high transmissibility and virulence of Alpha, Christmas 2020 was cancelled. However, during Wave Two testing topped 450,000 per day and, largely owing to the very low positive settings on the PCR machines, 3.8 million ‘cases’ were identified.

Whilst officially at least, this was the deadliest wave, with 95,000 people dying with Covid, because of so many positives, the ‘case’ fatality rate (CFR) dropped 10-fold to 2.5%. Yet this was also when Project Fear was gathering pace, so it comes as no surprise to learn that there were only 49,400 excess deaths during Wave Two/Three, similar to Wave One and only about half the official 95,000 estimate. This lower figure meant the implied CFR was now 1.3% (already a 16-fold better outcome than Wave One). Not that you’d have been alerted to these improved survival rates from watching the BBC News, of course.

Year Two

By pandemic Year Two (March 2021 to February 2022), Covid had become endemic and, instead of the prior big waves of infections and deaths, the official data show a steady trend of ~150 deaths a day, nevertheless sufficient to not only feed the insatiable appetite of the nightly BBC News, but to rack up a further 36,000 deaths, from 14.8 million ‘cases’, courtesy of 129 million tests (the CFR now being 0.24%, an 86-fold improvement on Wave One). Yet with Project Fear now in full swing and sceptical voices being cancelled, the somewhat inconvenient fact that excess deaths over this period barely totalled 11,000 (an implied CFR of 0.07%, or a 280-fold improvement on Wave One) seems to have escaped the attention of both the authorities and the mainstream media. Winter deaths (December 21st – February 22nd) were, in fact, 670 less than normal.

Year Three+

This was not all that evaded the authorities’ notice, however. Having over-estimated Covid deaths in Year Two by what appears to have been a factor of over 3x, an even bigger miscalculation, but in the opposite direction, seems to have been made with the most recent 18 months’ of data March 2022-August 2023. The Government’s official statistics show 42,150 cumulative deaths ‘with’ Covid, an average daily rate of 75 deaths, or about half the rate of Year Two. Given their tendency to exaggerate Covid mortality by a factor of 2x in 2020 rising to 3x in 2021, the true figure of deaths from Covid is probably below 15,000 and perhaps as low as 10,000. Compare that to a bad flu year pre-Covid, which could account for an additional 25,000 excess deaths.

Yet excess deaths in the eighteen months of Year Three+ were 78,575. If only 10-15,000 of these excess deaths can reasonably be attributed to Covid, then something else must have been responsible for killing 65,000-70,000 Brits over the last 18 months. This corroborates the 65,000+, non-Covid excess deaths figure we derived from the official statistics too. Yet on a topic this vital, it is important to apply more than just belt and braces.

Contrary to the practice of my namesake, Professor Neil Ferguson, it is necessary to consider the sensitivity of any model to its starting assumptions. The five-year period leading up to the outbreak of Covid, despite being the conventional baseline, was notable for not one but two bad flu seasons (2014-15 and 2017-18), which will have lifted the bar for ‘excess’ deaths. However, if we use the 10-year average monthly death data prior to Covid to smooth out this effect, we end up with higher numbers as expected, of course, but nevertheless the same clear message.

10-year average baseline

Wave One – Official death toll: 57,000. Excess deaths: 63,000, adjusted for dry tinder: 47,700.

Year One, Waves Two-Three – Official toll: 95,000. Excess deaths: 58,000 = a +64% overstatement.

Year Two – Official death toll: 35,700. Excess deaths: 19,400 = an +84% overstatement.

Year Three+ – Official death toll: 41,700. Excess deaths: 90,000 = a -54% understatement.

Given that even using the 10-year baseline, Covid deaths have been overstated by about a factor of +75% since 2020, Year Three deaths from, as opposed to with, Covid are unlikely to have been more than 25,000 at most (this is a higher nominal number because the hurdle for ‘excess’ is lower), implying once again that those excess deaths not explained by Covid have been in the region of 65,000, thus corroborating what we found using both the five-year average monthly death rates and the official HM Government statistics.

Conclusion

Therefore, while Covid fatalities may have been all but eradicated, there have nevertheless been 80,000-90,000 excess U.K. deaths in the eighteen months since February 2022 (to August 2023). If only 10,000-15,000 of them can reasonably be blamed on Covid, who or what is killing the remaining 65,000? No matter how you look at it, this new, unseen and unacknowledged threat is now killing ~4,000 Brits a month, roughly the same rate that Covid was killing during 2020-21. Yet, instead of broadcasting nightly death tolls and locking down the economy, along with any and all dissenting voices, this time there has been complete radio silence. Is this because the cause of death is inextricably tied up with taking medical advice from politicians, rather than medics? Worse, because this new killer is unlikely to be a new viral pathogen, it is also not likely to mutate into a more transmissible, but less virulent, variant over time. In short, until and unless identified and then restrained, this new killer could be here to stay.

James Ferguson is the Founding Partner of MacroStrategy, where this analysis was first published.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Let’s be pedantic, there was no pandemic only the one created by junk tests, corrupt experts and politicians and brought media. There was a lot of dry tinder and a lot of midazolam.

I hope Ed Dowd is wrong but a certain medical intervention is going to cripple society.

Lee Hurst gets ‘Tweet of the Day’, in my opinion, LOL! Further great posts from him in the comments section. I totally concur.

”Polite request incoming with impolite words:

If you are still going to vote Tory, after all they have done/are doing to us JUST FUCK OFF and stop following me.

You Are The Problem and I Fucking Despise You.”

https://twitter.com/LeeHurstComic/status/1715609636491968813

I think we’re beyond party politics, Mogs. They are all singing from the same hymn sheet, all marching to the same tune albeit in different ways to disguise their shared goals. Personally, I just can’t stand politicians. They are totally unfit for purpose, their purpose being to represent their constituents and bring any concerns their constituent have to a broader audience. Anyone writing to their MPs about anything that truly matters (freedom, liberty, choice, privacy, peace, human rights, sovereignty etc etc) gets a standard non-response. Parliament is dead from the neck up and down.

Too right👍!

650+ of the rats didn’t even turn up to listen to Andrew Bridgen’s speech for covid vaccine harms!

But they all turned up for the debate on mps pay awards! Go figure 🤔

A clear indication of their priorities. Me first, Me second and Me third, and the necessary financial awards required to support Me.

And here we all were, fully expecting a large turn out ( if not a packed room ) for concerned MPs to take part in and listen to the data presented at Andrew Bridgen’s debate on excess deaths. < max sarc > Totally scandalous that. I mean, we knew they couldn’t give a f*ck but now it’s just been confirmed ( once more! ) that they couldn’t give a f*ck. 🙁

Also, if you think you’re hearing more of the ”died suddenly” phenomenon that’s because there is indeed more people dying suddenly, as backed up by the above data. Particularly in people who have many more life years still ahead of them.

”IF YOU feel that you are seeing more and more news reports of people dying suddenly, that is because the data backs up this theory.

In the final months of 2020, there were on average 4,346 online news articles in English language media using this phrase.

In the first eight months of 2023, this figure has risen to 7,910 news articles a month on average. That is an 82 per cent rise.

Why are these time periods important? The final months of 2020 represent a time when the world was still gripped in the covid hysteria, but before the ‘vaccine’ rollout. A temporal marker so to speak of what ‘normal’ looked like for the phrase ‘died suddenly’ in our news media.”

https://uncut.substack.com/p/82-per-cent-rise-in-online-news-content?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

Do you remember the good old days when ‘died suddenly’ headlines were actually shocking, prompting urgent and strident calls for post mortems, detailed pathology reports, medical and sometimes police commentary, plus a terrible sense of loss? When weeping family members would make heartfelt statements to the press before requesting to be left alone to grieve? Now there’s an MSM blackout and anyone who speaks out is vilified and cancelled. How times change.

Yes I do and you’re quite right. They’re trying to normalize it and hoping that over time, if they can just ignore the problem for long enough, which is not going to go away, then we’ll become desensitized to it. They think we’re all stupid and as callous as they are. You do not need to be the one wielding the knife and getting your hands dirty to be the murderer. You are a murderer if you are the one orchestrating the events which leads to people losing their lives. This is what these politicians are, in my book, and ‘silence is compliance’.

Not sure if Hitler or Saddam Hussein ever got their hands dirty personally but they were no less murderous than the lackies who carried out their orders. And *all* of those politicians were pushing the death jabs but now they get to look the other way and not face the consequences of their actions?

The stark contrast when you are devoid of an intact moral compass ( or backbone );

https://twitter.com/CartlandDavid/status/1715620893374759145

Indeed, to paraphrase Basil Fawlty, “don’t mention the vaccine” (I mentioned it once but I think I got away with it). But it is a war, a one sided psychological war being waged by the government on the general population, who are taking all the casualties while paying through the nose for the privilege.

38 yr old model “died suddenly” of a heart attack. What could possibly have caused that ….. she didn’t look like a candidate for a heart attack to me. Still …. move along, nothing to see and definitely no questions to be asked.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12653049/Heartbroken-family-British-model-Tabby-Brown-pay-tribute-beautiful-person-larger-life-laid-rest-sudden-death-home.html

Here’s another one:https://thelibertydaily.com/was-it-jabs-viral-fitness-model-raechelle-chase/

44-years-old. She was a viral personal fitness influencer and model from New Zealand. Her cause of death has not been reported, which is standard operating procedure whenever vaxx-induced deaths occur.

But three deaths from Storm Babet is headlines and newsflashes. More proof of Climagheddon.

Well said👏

Did you hear the noise from the public gallery in the house when Bridgen stood to talk? Normally you cant because they are now behind bullet proof glass for security reasons (not f ing suprising!) so they must have been making one hell of a ballou to be heard in the background!

The people know what’s happening and the longer this intentional blindness goes on, the worse it will be for its advocates

I didn’t notice the noises from the public gallery, but presumably they were from supporters rather than from naysayers provided/funded by the government.

The noise was from the likes of Dr Mike Yeadon, Robin Monotti, Matt Le Tissier to name but a few. Stout defenders & supporters of truth.

I doubt cos play Dolan was there. Had a TXT from a mate who worked with someone, young, who was rushed to Hospital with multiple clots. The Dr actually told him it was probably the jab. He was lucky to survive.

That is progress. If only more medics would start to be honest.

Glad that they survived it.

I’m with Lee Hurst 100% but it’s ALL politicians and ALL parties..watching a lone Andrew Brigden surrounded by empty seats, made me want to punch the TV….

It was even worse if you watched it on BBC Parliament, I’m told….apparently the whole time he was talking there were banners underneath saying things like NHS say it’s safe and effective, there are no harmful ingredients in the vaccine etc…

It’s impossible for me to despise the creatures sitting in Parliament and the MSM any more than I already do…

..thanks to Modularist who posted the link to the egregious BBC actions BLT..

https://twitter.com/OracleFilmsUK/status/1715402666547757428

Sounds like CNN supposedly News channel doing advertising for Amazon.

Yes I agree. Actually Lee Hurst’s Twitter handle is; ”voteanyonebutliblabcongreen”, which I would concur with as none of them have the interests of the British people as a priority. None can be trusted. Yes the pitiful parliament situation really rams it home good and proper doesn’t it? These people are corrupt, self-serving and rotten to the core. But don’t they feel shame? Are they so stupid, or just indifferent, to the message their continual absence on this topic broadcasts loud and clear? There’s not even the pretense there that they care. Bizarre..

I don’t think it’s possible to make any remotely firm statements about “Covid deaths”

Ivor Cummings interview discussing vaccine deaths, 17 million world wide to date..

https://youtu.be/QQEY4DrRE5s?si=nBsdB2CMqYBP1WUt

If we thought the Covid and the vaccinations were bad then there is another even bigger one hitting us even harder coming up on the blindside. And apparently the King is going to be speaking at COP 27 about it. Climate Policies will kill millions more people here in the UK and worldwide than Covid and vaccinations ever did, yet our new King wants to encourage this absurdity.

Not my king!

Not mine either, nor his dom queen

I think our new King may go the way of the previous Charlies if he keeps meddling in politics.

And the irony is some actually think ‘climate’ will kill millions. As mentioned on Neil Oliver’s article….The worst oppressors are the ones who do it with a clear conscience.

Yep, the worst tyranny is the one who terrorises you for your own good.

The vaccine is killing and will continue to kill people.

We know it. They know it.

I agree, but three, four or five years from now who will link it with the quacksine?

Who will help them to pursue justice, as we can see already that people killed or injured are finding it difficult to get any compensation?…

I think in a recent interview the America Lawyer Aaron Siri from the Highwire/ICAN team said that only four people have been paid-out in America…?

I honestly sit sometimes and look at friends and family and feel sick with trepidation as to what might happen in the next couple of years….

To me it’s clear they intend to do a “Hillsborough”

By that I mean deny the problem and the kick the can down the road as long as possible.

If it takes another 30 years to come out (like Hillsborough) most of those involved will have left public life, died or just be “unfit to stand trial”

Did you hear the woman after Andrew’s speech, she was actually blaming excess deaths on the return of the flu.

Whenever I hear someone out in the sleep-o-verse saying that so-and-so died or got cancer or an auto-immune disease etc these days, I have to grit my teeth and bite my tongue. The way that this is just accepted is horrifying. This is amplified if it’s a young person. Words such as ‘tragedy’ and ‘awful’ are used whereas I want to say ‘No, it’s criminal, it’s state sanctioned murder!’

When I hear of a sudden death, strokes, heart disease, cancer etc. I always ask if he/she has had the jab. With the exception of one lady they all have.

No need to say any more really.

“Is this because the cause of death is inextricably tied up with taking medical advice from politicians, rather than medics?” Or perhaps medics taking political advice from politicians?

Do bear in mind medics are salesmen for the pharmaceutical industry and politicians are looking to their future as consultants, on boards, jobs in international organisations, so they will sing whatever song their potential paymasters want them to sing.

“Something Is Killing Brits as Fast as Covid Did”

Answer:- Covid vaccines

Let’s stop pussy footing around and call a spade a ♠️

And, Andrew Bridgen is a fecking honorable trustworthy bona fide hero!

The second peak Dec2020 to Mar 21 coincided with the initial roll out of the vaccines to the elderly. The result was the deaths of over 75s was 25,000 more than in the same period 5 year average up to 2019. Many more people got Covid inc frontline staff who were virtually all vaccinated. Staff who hadn’t caught Covid19 in the pre-‘vaccine’ era. The ‘vaccines’ killed and are killing and harming. And they knew the potential and real harms. This wasn’t ignorance, it’s criminal.

Well one thing we do know is that whatever is killing people it certainly, definitely, absolutely, irrefutably, is not the mRNA gene therapy pumped repeatedly into the arms of a large proportion of nitwits in our society.

And rather than excluding the 15 000 or so CoVid deaths, should we? The evidence points to ‘vaccine’ compromised immune systems which can’t handle even the milder variants. So are there excess CoVid deaths?

Follow the Science Remember the Vaccine Injured –

leaflet to print at home or forward to politicians, media, friends online.

Government sources are seemingly hiding the death stats, but surely actuary and life insurance company data would show the damage. I’m visiting my niece who is a VP actuary for an insurance company. I asked her 9 months ago about the increase in sudden deaths. She breezily told me, “Overdoses,” and then suddenly needed to go into the other room. I’ll try to pin her down this visit. Are actuaries and life insurance companies being told to hide the data or do companies not want to let investors know that they’re losing money? Working age people with good jobs and life insurance benefits are seemingly healthier than average and are unlikely to be dying from “overdoses.” I too was shocked at the empty green around Mr. Bridgen yesterday.

…although no one was in Parliament I suspect Andrew’s speech will be seen by literally millions today on social media…

..that empty room will be seen around the world….

There isn’t more than two or three sitting MP’s I would give the time of day to…and millions of us think the same…so I hope the money has made them happy….

The other organisations that uses actuary assessments are private pension schemes. Every so often they have to update them, and maybe increase the level of annual contributions. However, they’re usually coy about increasing outgoing payments when life expectancy declines.

Could that ´mysterious new killer´ possibly, just possibly, be the jabs?

Andrew Bridgen’s adjournment debate on excess deaths is here: https://www.bitchute.com/video/snMAuGXSbR81/. There was an abysmal turn-out of MPs – looks like just 15.

This has not been reported here! Buck up, Daily Sceptic!

My calculations show about the same excess deaths over the last year as three years ago – the so-called ‘pandemic’ year. And deaths of children aged 10-19 since the beginning of 2023 is 18% above the average 2010-2019 (corrected for population). This is extremely concerning!

Daily Sceptic have today published the whole text from Andrew Bridgen’s addess. Thanks! That’s more like it guys!

It isn’t just the deaths, what about our decline in health? My Victorian grandparents seemed far healthier than people today.

Yes let’s start with the Politicians on Both sides of the commons…..

And where were the 600+ MPs when Andrew Bridgen presented data on excess deaths post covid vaxx. They were hiding in their surgeries. Could not be bothered to learn what has happened to the thousands of Brits who died after they took the covid jabs. That is okay, the truth is seeping out and these MPs will be as guilty of causing injury and death as the doctors, nurses and gov’t officials who pushed these dangerous and ineffective jabs on the public

In summary : Approx 1,000 people are dying every week in the UK as a result of this mystery.

One thousand a week above average.

Incredible.