From coronavirus to climate change, scientific discussion has been stifled by the ‘settled science’ trope. As a long-term analyst and careful critic of medical papers it annoys me. In 2000 I began a column in the journal of the British Society for Rheumatology (conveniently titled Rheumatology) trawling the journals for interesting, unusual or bizarre pieces of research, which I would dissect for my readers. Five years as a columnist honed my critical eye.

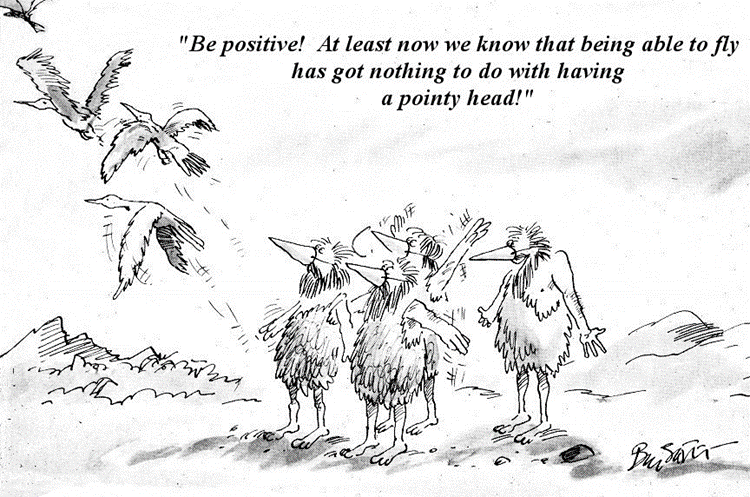

One cornerstone of medical research is the null hypothesis. You set up an idea and try to find something that knocks it down. A parallel concept is that of the Black Swan, where a plan is derailed by an unexpected event. In each case a single observation or fact which disposes of the hypothesis is sufficient for its abandonment. Bill Stott encapsulated this in a brilliant cartoon in Punch some years ago.

Various doctors have described how one of their teachers would tell them that, after five years, half the things they had been taught would be shown to be wrong, and the problem was that you didn’t know which half. But it underpins the argument that medicine – and by extension science – is not a static subject and is always subject to change. There are endless examples of how scientific consensus has been disrupted by a contrary observation which pulls the whole house down. Some are well-known, some less so. Here are a few. As you will see there are different mechanisms and causes.

Settled science said the Sun went round the Earth until Galileo and Copernicus made observations that proved it did not. Both were lone voices and suffered for their beliefs. Settled science said that cholera and puerperal sepsis were considered miasmic conditions until John Snow conducted a controlled trial proving the former was water-borne and Ignac Semmelweis conducted a similar one for the latter. Snow’s work took some time to become accepted, while Semmelweis’ work took longer, no doubt in part because of the way he presented it and attacked his disbelieving colleagues.

Before 1921, settled science did not know the cause of diabetes. Then Banting and Best discovered insulin, though Paulescu in Romania was the first. So settled science then began to understand that insulin lack caused diabetes. But then it became apparent that there were distinct types of diabetes and that insulin lack was not the only cause; insulin resistance could occur. Then it was found that insulin lack might be caused by an autoimmune reaction destroying the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Then the hormones glucagon and later leptin were discovered. Diabetes was no longer due to failure to produce insulin alone, and diabetes became as confused as it had been at the beginning of the 20th Century. No settled science here.

Some infections of unknown cause were found to be due to viruses – but it was not until it was possible to see these microbes that cause and effect could be adduced. Similarly, the understanding of inflammatory processes and the realisation that white blood cells held a key role in disease transformed rheumatology management, but, just as with diabetes, the exploration of the inflammatory response changed the science. It was not just white cells; these now were subdivided into T-cells, B-cells and macrophages, and then the T-cells got further divided into T-helper cells, T-suppressor cells and T-null cells, and then the inflammatory chemical cascade ran amok with the discovery of all sorts of interferons and interleukins, the number of which latter is unclear (search Google using “how many interleukins are there” and you will find varying estimates from 30 to over 60). I have sat through many lectures describing the inflammatory cascade and the slides become more complex by the week. In these examples, advances in science – here immunology, biochemistry and microscopy – were key to unravelling mysteries and taking down hypotheses.

In the 1970s some research pointed to the possibility that rheumatoid arthritis was triggered by infection with the infectious mononucleosis virus. This hypothesis was confirmed in a couple of laboratories, only to be knocked flat by the discovery that the original results were due to contamination. So, one may argue that the revelation of faulty research led to a change in understanding (or belief). Belief also caused patients with back pain to be put to bed, often in hospital and in spinal traction. After all, who could argue with the concept that such pain should be treated with rest? I didn’t; sometimes I had four or five back pain patients in my ward. We had always done it, we were taught to do it and so we went on doing it. It was settled science. But in fact no-one had done any research to compare bedrest against ambulant treatment and when they did – if ever there was a medical U-turn, that was it.

Settled science relies nowadays on clinical trials. But have these been properly conducted? In other words, is the conclusion justified? Was the sample size sufficient to prove the case? Was randomisation properly done? Have the correct statistical tests been used? Have confounders been accounted for? Have all the data been properly analysed? Were there any conflicts of interest that could have influenced the publication of results? Have the conclusions been fairly presented? Have the data been open to outside inspection? Statistical teaching in medicine is patchy and I certainly would not profess to be a statistics expert, but others are and I can rely on them.

There were numerous trials of anti-inflammatory drugs in the 1970s which had too small sample sizes, and several which concluded that drug A was similar in efficacy to drug B, although re-analysis merely proved that the trial had failed to show a difference, which is not the same. Many trials used the wrong statistical tests and were improperly randomised or excluded specific groups. Patient selection for trials? Benoxaprofen (Opren) was deemed safe but had never been tested in older people who, it transpired, metabolised it differently and in whom it was far from safe. Similarly a preparation of oral gold (for rheumatoid arthritis; injectable gold was the mainstay of therapy in the 1970s) had pharmacokinetic data showing two patterns of drug clearance judged by its half-life in the body, but the sample size was small. Only one patient showed the second pattern of delayed clearance – but this was 15% of the sample, yet the analysis ignored it. Extrapolate to a population and you can see the problem; as it turned out, the population did show such a dichotomy and the delayed clearers had a higher incidence of side-effects due to drug accumulation. Some trials excluded dropouts from analysis and thus failed to assess properly why subjects failed to complete the trial. Conflicts of interest? Some trials were and are conducted by drug companies or by researchers receiving large grants from them, and negative results are often concealed. Positive results are great, but when looking at the risk-benefit analysis it is important to compare like with like. Thus, if a statin trial shows a 50% reduction in cardiac risk, what is that a 50% reduction of? If the absolute risk is 5% then a 50% reduction drops the risk to 2.5%, which is not huge. Often the risk is presented in absolute terms and compared with the benefit in relative terms, which is scientifically dishonest. And all too often the raw data from such trials are not offered up for independent analysis, with the feeble excuse that it is commercially confidential. All of these unsettle settled science.

The explosion of genomics has led to the unravelling of numerous medical mysteries, in particular in hereditable disorders and inborn errors of metabolism. Fifty years ago this would have been unthinkable, but science progresses, we find out more things – and we find things that undermine current opinion, as Einstein did with gravity and new space telescopes have done with quasars, black holes and other studies of the universe. If we did not find those things and realise that science can change, we would still, perhaps, think the Earth was at the centre of the Universe.

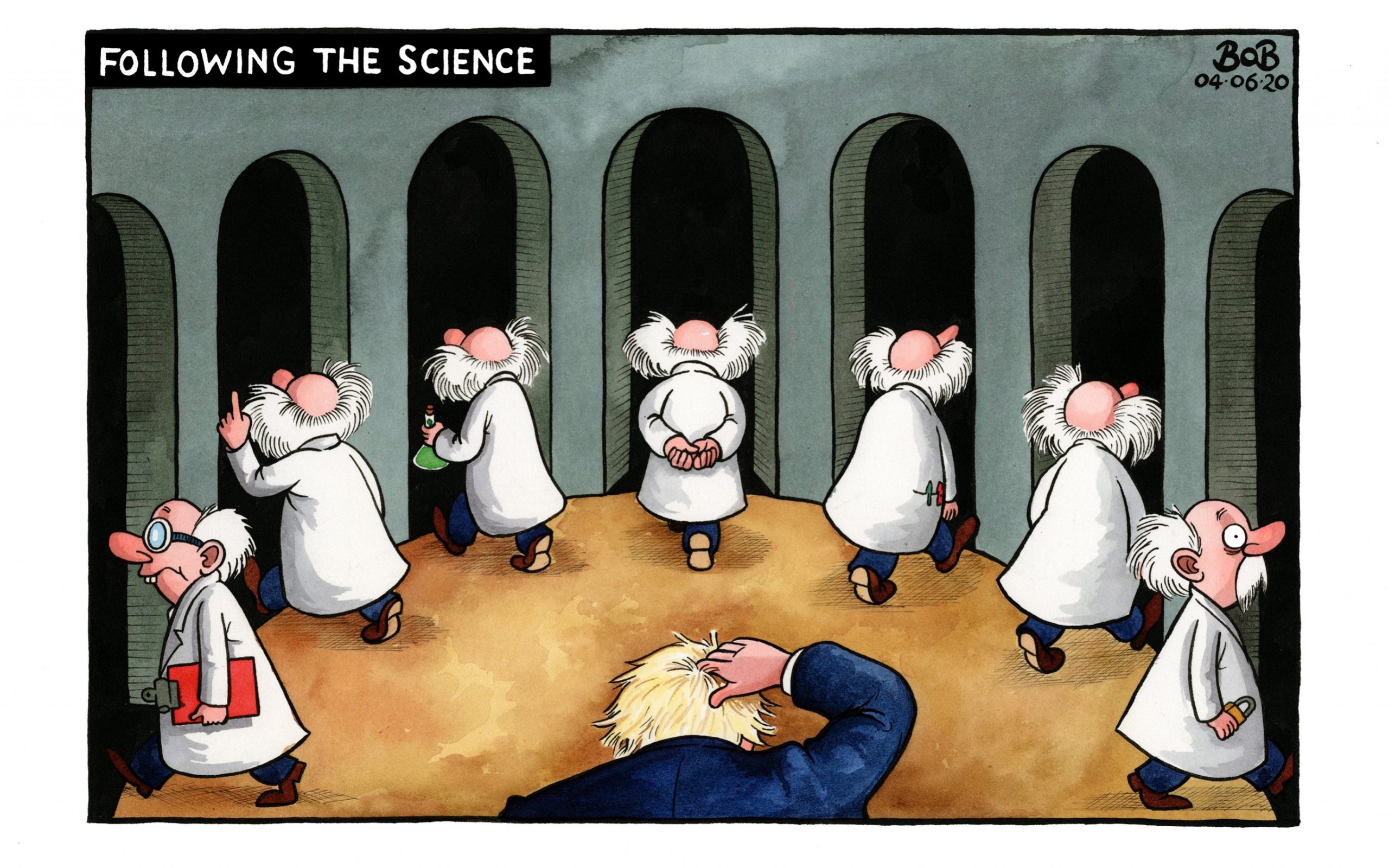

In today’s context we have the twin issues of SARS-CoV-2 and climate change. In the first case we have been led to believe that settled science proves that lockdowns and masks work and that the virus was of natural origin. In each case unpicking of the data, some of it concealed for whatever reason, undermines all three conclusions. We were bamboozled into believing that settled science showed that there would be an explosion of deaths, failing to see that the conclusion was not based on facts but on prophecy. We were told that settled science proved that vaccines were safe and effective, but when doubters asked for the evidence, this was largely absent, and our belief that settled science had proved the safety of m-RNA vaccines was destroyed by analysis proving significant DNA contamination. There is a hypothetical risk to this, but that risk remains unquantified if indeed it exists at all, but it is unsettling to think there might be a significant risk. Would it not be safer to do some long-term studies before exposing a global population?

The debate on climate change has also relied on models, and settled science activists have brushed aside the GIGO axiom – garbage in, garbage out. They have also failed to quantify the relative contributions of fossil fuel burning, volcanic eruptions, solar storms and sunspot activity, changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, deforestation and water diversion and failed to understand the effect of urbanisation. In plunging headlong into the promotion of so-called renewable energy they have also fallen into another common trap – that of proclaiming the benefits while failing to analyse what could possibly go wrong. If, as I was told this week, five of 50 luxury cars of the same marque had to be returned to the saleroom for replacement of their batteries after less than two years, what are the costs both to purchaser and manufacturer? If spontaneous combustion risk causes insurance premiums for such vehicles to become unaffordable, what is the future, let alone the likelihood that demands on electricity supply will become unmanageable, so the cost of recharging goes up and also becomes unaffordable? And this set of risks excludes any analysis of whether the climate is really changing as dramatically as the prophets foretell, which factual evidence seems to contradict.

When sceptics raise all or any of these contradictions they are disparaged as vaccine deniers, climate change deniers and dangerous fanatics. If there is doubt, then say so. There is nothing wrong with saying you don’t know. While there are undoubtedly some proponents of wacky conspiracies lurking in the undergrowth, the huge majority of sceptics have merely analysed the data in a scientific way and unravelled the settled science consensus. And then the settled scientists themselves become deniers because they are too rigid to change their minds despite the revelation of incontrovertible facts.

These few examples lead to the inescapable conclusion that there is no such thing as ‘Settled Science’. Such science may be informed by dogma, belief, poor research, inadequate information and even fraud. New investigative techniques, re-analysis of past work, repeats of trials in the light of new knowledge all confirm that science may change. ‘Settled Science’ is an oxymoron. Let’s leave it behind.

Dr. Andrew Bamji is a retired Consultant Rheumatologist and author of Mad Medicine: Myths, Maxims and Mayhem in the National Health Service.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Climate change is not science, at least in the case of miasma or aether theory these ppl were not malevolent. Those were reasonable attempts to describe complex problems. Climate change on the other hand is merely propaganda from the Geobells school, ie repeat a lie over and over till ppl believe it and suppress all dissent. This lie is then used to regulate every aspect of our lives. I’m sorry to say we have woken up from a slumber and live in what is fundamentally a vicious socialist dictatorship.

A superb article.

Just because we live in the modern world and that as such science has progressed especially with the aid, lol, of computers (can we really “see” a virus for example) there is a tendency to assume that is what is known now is definitively correct. Aka known as arrogance.

Should be compulsory reading, especially for those ostensibly in charge.

A further illustration is that of the fight between the contagionists and the anticontagionists re the spread of disease.. This fight has been going on for hundreds of years and is still far from settled – what actually causes illness, lockdowns work/don’t work, – masks, distancing etc.

The real problem is that matters medical and climate have been captured by politics and as such the unthinking public is too easily fed a narrative by the complicit MSM.

They censor and dictate what is true and not true – to the detriment of us all.

We don’t have science any more when issues are highly politicised. We have Post Normal Science. Not the same thing at all.

Scientism or the religion of science for power, money, control. A 200 year old project. Saint Simon, Comte et al and their Churches of ‘Science’. Irrational, deranged.

Evolution, the Big Bang – all junk as well but of course studiously left out of said article. Shrew to you. Whatever. Theories with so many Gods of the Gaps and hopeful monsters, including abiogenesis, they make Al Gore look intelligent.

But we don’t try to control the worlds wealth and resources using evolution or big bang theories. —–No one cares if they are true. I won’t have to rip out my gas central heating and spend 20 grand on a heat pump based on what someone tells me is true about black holes or evolution. Climate Change and the phony policies to fight it on the other hand will directly me and everyone else.

Exactly I feel many conspiracy theories are actually invented by the state, exhibit A would the flying saucer stuff which just happened to coincide with secretive testing near military baes. We need to worry where science is abused to control us. The actual truth of evolution, quantum mechanics etc is totally unimportant.

Scientific consensus gives me an ulcer

Read up about how stomach ulcers were improperly treated for decades to enrich big pharma.

Good peice👍

If science is ever ‘settled’ then it’s not science!

Nicely pitched. Could be room for a paragraph on cancellation of dissent: Alimonti, Pascal Richet, Judith Curry et al. Money hates heresy.

Through out science the consensus has often been wrong. Look at Black Holes, and plate tectonics etc etc. It should really be based on evidence, and not opinion or what somebody feels is right. Unfortunately how you do this is a bit more slippery than you might wish for. Complex systems like the human body, you have to take a risk type of approach, as there are so many complex cofounding factors. It is perfectly possible for somebody to smoke 10 a day, and live to 90, whereas somebody who doesn’t can die young due to other factors, including bad luck. Hence, things like RCTs, where you can do them for ethical reasons (for smoking you can’t). Unfortunately various things can corrupt the process, whether it is political, people’s reputation, money, power, and that often it is very difficult emotionally for somebody to admit they are wrong, and it is also difficult to go againt the consensus.

Oh yes, and if somebody states a scientific ‘fact’, it is always worth asking- “how do you know that?”. Nothing like getting back to the basics to clarify the mind, plus it makes science interesting (if you can past the jargonese).

“Settled Science” is really just “Official Science”. ——-It is the last refuge of scoundrels using “science” to bludgeon us all into accepting what officialdom want to be true and knowing that if we think it is all about “science” we are mostly not likely to question it. After all, if all scientists agree then who are we to disagree? Except all scientists do NOT agree and never did. So is this what science has become? Just another government department?———But what many don’t realise is that most of this climate change stuff isn’t actually science at all. It is modelling. It is speculations assumptions and guesses chucked into a model. But models are NOT science, and they are NOT evidence of anything. Climate Change is a pseudo scientific fraud, and it is all funded by government. —–If it were funded by the fossil fuel industry there would be spitting fury that they were using the science to support their agenda, but what makes people think government have no agenda? ———Ofcourse they do. It is called Sustainable Development. But I will leave that for another day.

Has Soviet Self Censorship come to Britain?

Fat Pig News Investigates!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIO3fJpnXLE

Donald Rumsfeld summed it all up with

Oh, that’s a good one👍

His usage in the context of the Iraq war and WMDs sadly tainted a very useful concept (or model) known as the JoHari window (after Joe and Harry). I’m looking forward to the time when Kamala Harris resurrects it and incorporates it into one of her legendary enlightening and erudite monologues. Perhaps she already has.

Its regular use in other contexts might just let the light in for.

“GIGO axiom – garbage in, garbage out.” Especially when the ‘model’ the garbage is being fed into is also garbage.

The problem was in thinking that ‘science’ was a destination rather than a continuous journey. The same could be applied to religion. It’s when these disciplines/beliefs become entrenched and dogmatic that problems arrive. Scientists should know this. So should those funding scientists and the media. In fact, anyone who has one iota of intelligence and the ability to think clearly and critically should too. The fact that all these ‘clever dicks’ say that the science is settled is massive piece of gaslighting. They are lying to us on such an enormous scale that they must think that most of humanity is largely ignorant. Sadly I think it is.

Of course science is never settled in the sense that it is always possible that it might be overturned. I don’t think any serious scientist would disagree with this and to attack it is to attack a straw man.

However science can be more or less certain, you could phrase that as more less settled. And we have to make decisions based on current science even though there is always some uncertainty. I am sure that when Doctor Banji was practicing there were some elements of medicine which he assumed to be true and on the basis of that made his diagnosis and treatment – for example I have no doubt that he considered it settled science that there are red and white blood cells and that white blood cells have a key role in inflammatory response. I am sure he is right. That’s not the point. The point is that it is settled science. Settled in the sense that he is sufficiently sure of it that he will base his treatment on it.

In the same way the main assertions of climate science might be rejected at some time in the future. It is always possible. However, we have to make decisions now. This is further confused by mixing up the many different assertions that are involved in climate science. Some of these are more settled than others. It is for example very settled that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has increased by about 30% since about 1850 and this is the result of human activity. It is also very settled that the increased presence of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will raise global temperatures to some extent. What is less settled, and this is a matter of degree, is how big will that increase be given further increases in greenhouse gases, and what will be the consequences.

There is no such thing as “more or less certain”. You’re either certain or you’re not certain. If you’re certain, you have no rational doubt. If you’re uncertain, you have some rational doubt.

You can be more or less confident that something is true, but you cannot be “more or less certain”.

In the same way, there is no such thing as “assertions“ which are more or less settled. If they are “less settled”, they are not settled. If they are settled, there is no point in describing them as “very settled”. They’re either settled or not settled.

Very little is settled and very little is certain. Science is full of assumptions, and medical treatments can work or appear to work for reasons which are not the reasons they are believed to work.

“More certain” and “less certain” are common figures of speech but I won’t argue over definitions. The fact is some science is extremely well established – whatever you word you want to use and some science less so, and there is a gradient from one to the other. Sure you can see that?

Yes, I can see that. We can be very confident that some things are true, without being certain, and we can have less confidence that other things are true but still believe they are true.

And?

Spending trillions reorganising the global economy based almost entirely on the output from dodgy climate models that don’t include many of the parameters because (a) they are poorly understood or (b) because they are unknown is NOT science. Real world observations do not indicate a climate emergency. The fact that models full of assumptions might suggest a crisis is irrelevant. But it is the models that governments base policy on.————-Oh how convenient. A Political body called the IPCC with a clear remit to look for everything in the climate that might be caused by humans but with zero interest in what the natural climate might be doing is POLITICS not SCIENCE. The politics of Sustainable Development. Pseudo science not science

My point is that it is pointless arguing about whether some scientific assertion is settled or not. The key thing is whether we have sufficient confidence in the assertion to act on it given the circumstances.

(I would add that contrary to the headline of the article there is some science that is “settled” in the sense that you would have to be an absolute nutter to think it will ever be overturned. For example, that the earth orbits the sun or Harvey’s theory of the circulation of the blood).

The headline is not suggesting that nothing in science is “settled”, but that a lot of what we are told is “settled” is not “settled” at all, such as climate change, Coronavirus, the safety of vaccines, the effectiveness of vaccines, etc.

The problem is that too many scientists and the media reporting on science do not acknowledge that an awful lot of scientific findings are based on assumptions which may or may not be true, and therefore their findings may or may not be true.

Occasionally, there is some honesty, but it quickly gets forgotten about and ignored:

According to this BBC News article in 2017:

“Most scientists ‘can’t replicate studies by their peers'”

and then within 4 years the BBC wasn’t allowing anyone to even question Big Pharma’s claims with their obvious massive conflicts of interest!

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-39054778

Similarly, according to Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancet, in 2015:

“The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue.”

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60696-1/fulltext

And there was this:

“Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”

– John P. A. Ioannidis

Published in Public Library of Science Medicine, 2005.

“There is increasing concern that most current published research findings are false.”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7686290_Why_Most_Published_Research_Findings_Are_False

So it may be true, as you say, that “it is pointless arguing about whether some scientific assertion is settled or not’, but not for the reason you are suggesting, but because it gets ignored!

The headline is not suggesting that nothing in science is “settled”

Maybe not the headline but the author finishes with:

These few examples lead to the inescapable conclusion that there is no such thing as ‘Settled Science’.

Do you agree?

I agree in the sense that the author meant, and apparently you agree too:

“Of course science is never settled in the sense that it is always possible that it might be overturned.“

The author is not suggesting that there are no proven facts. He didn’t say there is no such thing as settled science. Instead he put “Settled Science” in inverted commas and he capitalised both words.

The author isn’t criticising those who claim there are provable facts, he is criticising the attitude and idea of “Settled Science” which shuts down debate and isn’t actually science.

If it were only science we were talking about then you might have an argument. But predictions as to the future of climate are based mostly on models not science. I recall one of the well known “scientists” from NASA saying exactly that. He said “we don’t base predictions on the data, we base it on the models”——–But here is the problem. Models are NOT science, and they are not evidence of anything.

Here is a nice piece on the role of models in science:

https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/575-scientific-modelling

While I don’t personally think it can….It actually doesn’t surprise me at all that many people believe science can be settled.. in fact in this time of oppressive Global/Government/MSM agenda driven consensus, I’d say it was a natural conclusion….

It seems to me that we live in a world where we are constantly, told, pushed and nudged into believing that there’s a ‘right way’ to think about everything……pick any subject…

Everyone is encouraged to believe there is a single truth…and it only comes from them, (just like Jacinda told us)…..and of course, you are the Anti-vaxxer, Putin Troll, Trans hater, anti semite, climate boiling facilitator….etc etc ….if you dare to even question….

Why would we think that science is the one subject where people, who are ably assisted and led into every other ‘settled opinion’…would suddenly become sceptical and apply some critical thinking about science?

As a matter of interest how many people think that it is not settled that the earth orbits the sun?