I have spent almost half my life ‘within’ the NHS mental health system. For over 15 years I have needed and depended upon its services and support. If I reach a state of crisis, I have to attend their facilities. And I have been many times. I have had severe depression, self-harmed and attempted to take my own life on several occasions.

Over the years I have seen both the good and not-so-good sides of the institution. I have been the subject of physical restraint procedures, now disallowed, such as being forced face-down onto a bed. But I have also been the recipient of individual acts of kindness, and the official protocols have improved as well. In fact, notwithstanding some blips, I believe I was getting ‘better’. I saw the power and positivity of ‘good mental health’ practices, and before March 2020 was doing a course with the aim of becoming a counsellor.

However, during the past three years of Covidian madness I have been exposed to a side of the mental health establishment that I can only describe as systemically and institutionally abusive, with some staff who seem to have either lost – or never had – the most basic qualities of empathy and consideration for vulnerable people in their care. How else would you describe a situation where, having recently tried to kill myself, I was sitting in front of a doctor, tears running down my cheeks, begging to be allowed to remain maskless, only to be told that she “had a duty to protect and keep safe people vulnerable to the virus”?

In mid-2020, when mask mandates began to appear, I contacted my local NHS Trust, Mersey Care, to clarify my situation regarding exemption. Their reply reassured me that, as I was legally exempt, I would have no difficulty accessing their services or buildings. They further buoyed me by saying that this was official policy and would be communicated to all staff within the trust.

Hearing this was an immense relief. My conditions include Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder as well as anxiety and I have a history of trauma with symptoms of PTSD. Wearing a mask – and being around others wearing them – is extremely challenging.

Without seeing facial expressions, communication becomes very difficult, and my anxiety causes me to experience panic attacks which masks and shields ramp up in their intensity. Basically, masks trigger flashbacks, which lead to panic attacks which in turn result in me hyperventilating. I become dizzy, feeling like I’m suffocating.

It’s distressing and I cannot focus on anything around me. I’ve tried to wear a mask, but the longest I’ve managed to go without experiencing these symptoms is a couple of minutes.

I can’t use face shields because my breath fogs and becomes humid which triggers the same problems. It’s an endless and escalating feedback loop of alarm and confusion.

A little later, during a time of great personal crisis, I had to attend my local psychology services department. The Psychology Services Hub acts as a sort of therapeutic community, one that I’d been familiar with, both as a patient and a service user lead volunteer, for many years. Indeed, as the two senior managers of the hub had been therapists of mine, I was well-known.

Feeling very suicidal and having let them know in advance that I wouldn’t be wearing a face mask, the day I was due to attend an assessment meeting my urgent appointment was delayed for several hours. The reason for this, I was told, was so that the “team could debate allowing me in”. On this occasion they did permit me to enter the building. However, the next time I needed help with my intense suicidal feelings it was made clear that without a face covering I would not be admitted.

Pointing out that I had emails from Mersey Care’s Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) team confirming my exemption made no difference. Nor did quoting the 2010 Equalities Act. I was not to be allowed in without a mask.

In the middle of June 2020 I submitted a complaint to Mersey Care’s Patient Advice & Liaison Service (PALS). I was contacted by the IPC team, receiving emails and phone calls, as a result of which I was assured that the trust was reminding all staff that mask exemptions applied to all buildings and services.

Some Mersey Care facilities, for example Life Rooms in Bootle, honoured these commitments and allowed me in without a mask. My hub did not, and despite calling IPC and PALS repeatedly it took 17 months for a response to my complaint to be given.

During those 17 months my mental health deteriorated badly. It is difficult to put into words just how devastating this was. Ironically, at a time that I was starting to do well with my mental health, it was the catalyst that resulted in a complete breakdown. I think it was the shock of discovering that, of all the people in the world who I thought would be compassionate and understanding about this issue, staff at the hub, part of an NHS mental health trust, were the worst. Even Sainsburys, with their signs and loud-speaker messages reminding shoppers to be mindful that people not wearing masks could have hidden disabilities, made me feel safer and more welcome. What had it come to when supermarkets are more understanding and reasonable than a mental health service?

I completely lost faith in the service. I lost faith in people. I felt strongly that if mental health care professionals would not accept my mask exemption on the grounds of mental health, then no one would. I became terrified of judgement from other people. If the mental health services could be this harsh and discriminatory then what would I face from strangers?

In addition, I became isolated, sometimes going eight weeks at a time with zero human contact. My panic attacks became more frequent and more intense and I eventually reached a point where I was too afraid to leave the house by myself and do basic things like go shopping or pick up medication for fear of judgement and lack of understanding from others. I developed agoraphobia and I became addicted to anti-anxiety drugs as sometimes they were the only way I could manage to do something as simple as food shopping by myself.

I was too afraid to access any kind of healthcare. Simply, I came to feel that I wasn’t legally allowed to access services and I was terrified as to how Mersey Care would act towards me. Surprising as it might be to someone who hasn’t seen the mental health system from the inside, patients who come to be viewed by staff as ‘troublemakers’ may find themselves on the receiving end of retributive action. Those who are considered to have broken ‘community rules’ may be suspended or excluded from accessing services.

Because I was too scared to attend the surgery, when my GP wrote to me about things like smear tests or check-ups, I ignored the letters. In December 2020 an untreated UTI led to a severe kidney infection that, because I delayed seeking help for too long out of fear, eventually left me in hospital for a week.

At the same time my mental health declined further. I began self-harming again and made attempts to end my life. Often taken to the hospital forcibly by the police because of the fear I developed, I was sectioned and hospitalised on multiple occasions.

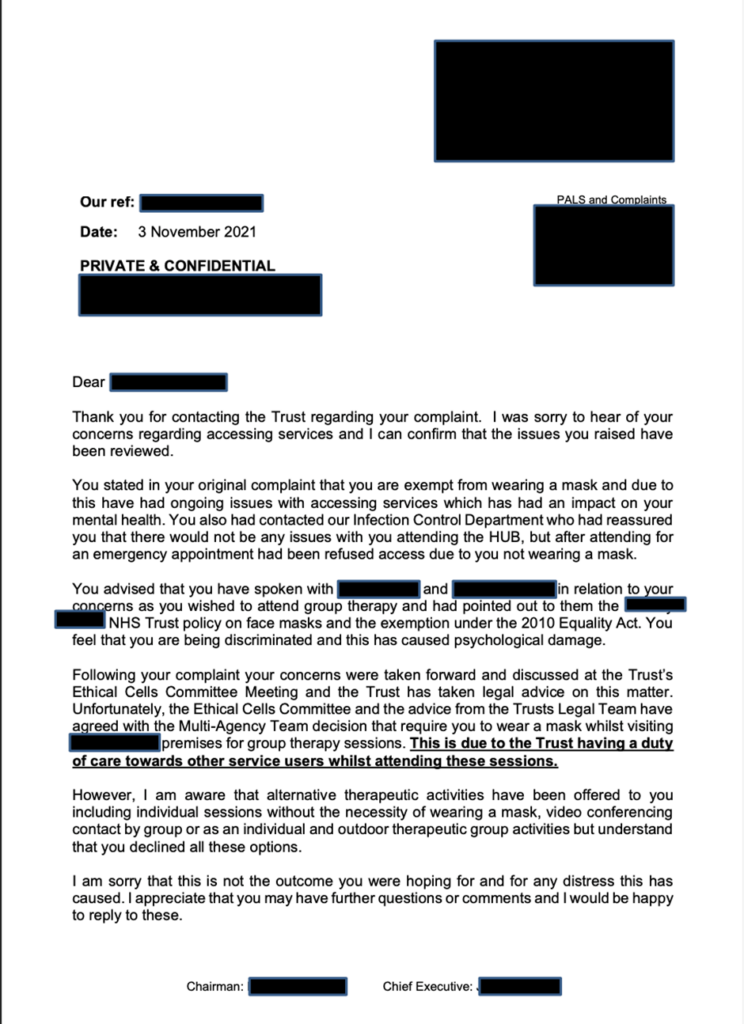

Eventually, in November 2021, after numerous chasing emails and calls, I found out that Mersey Care had not upheld my grievance. It remained a requirement for me to wear a face mask or shield to visit my hub. The reason for rejection? Mersey Care’s Ethical Cells Committee, acting on advice from the trust’s legal team, determined that Mersey Care had a “duty of care towards other service users”. That’s the sum of it. No evidence underpinning this decision was provided. My wellbeing counted for nothing: not even a proper explanation.

At the same time as I received this rejection I was told by the doctor who runs the hub service that he interpreted my complaint as an “act of hostility” against himself. I was warned that if there was any further “hostility”, I risked being discharged from Mersey Care services all together.

Angered by what I perceived to be an injustice, I did contact a national legal advice line, but they told me that because my case had a less than 50% chance of winning in court, they would not provide me with legal aid. I have no funds to hire a solicitor independently.

Taken as a whole, I am left wondering just how a mental health trust can be so uninterested in its clients’ mental health. Perhaps its promotion of support for people struggling through the pandemic, its trumpeting in the 2019/20 annual report of “zero suicide” ambitions and statements about “striving to provide perfect care and a just culture”, and its boasts that it is “committed to equality and ono-discriminatory behaviour” is all just window dressing?

Since the start of the Covid period I have come to feel as if, like a leper, I’ve been cast out. Not only did my conditions make it impossible for me to function while wearing a mask, my own research told me that masks offered no positive benefits. At home I watched morning TV and heard so-called ‘celebrities’ declare that “people who don’t wear face masks should be in the stocks, in prison, or hanging in the streets”, and when expressing my scepticism about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 counter-measures to Mersey Care, a doctor asked me, with an exaggerated eye roll, “Are you a QAnon person?”

I am the one who, because of my conditions, is supposed to be irrational; yet I have asked myself many times why people working in a ‘caring profession’ and who profess to be scientific in their approach should act with so little feeling and so little logic. The only answer I can think of is that this matter is now personal, not professional, between us, and they really don’t care what I think or how I feel. Perhaps the alternative, that they really are this lacking in basic humanity and so fully absorbed into the Covidian sect created by the Government’s propaganda and manipulation, is too shocking to contemplate.

The author is a supporter of Smile Free, which campaigns for the end of mask mandates and masking.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I know where the anonymous is coming from. I lost about 70% of my hearing due to an accident when I was in the military. Over the years I have sub-consciously learnt how to lip read, these masks have been a nightmare, explaining the situation to most people with mask on, they dont care.

This is from the poster known as ( if I recall correctly ) ‘WhoshotJR’. I was wondering how this person was doing as they made brief contact then disappeared. I was concerned about their wellbeing and would be very relieved if they could drop by again, just to check in so that we can make sure they’re ok. You did an awesome, heartfelt post which really touched many of us here. Hope you’re OK..

I recognized this, too, but it’s with a few more details, eg, the duty of care letter.

I feel compelled to point out that in the letter here they state they offered me individual therapy and I refused, but this is completely false. I was offered a choice of two different group therapies depending on the condition that I wore a mask which I obviously couldn’t do.

All may not be lost for you in accessing appropriate support. There is a Mental Health Nurse in Liverpool, who is a member of The People’s Health Alliance & takes one’s financial situation into consideration.

I wish you well.

https://the-pha.org/practitioners/kimberley-rogers/#post_content

Thankyou, that’s actually very helpful 👍

One of the most disturbing aspects of this experience has been having my mental health destroyed by the people I’m supposed to turn to for mental health support. I have been looking for a therapist that can help me deal with the trauma of these past three years, but alas most are staunch covidians who don’t see anything wrong with what was done to me.

It really is hard to find someone right for you, particularly when it’s the NHS as you’re forced to take what’s on offer…

Separately my friend is being counselled by a (very nice lady I’m sure) about her relationship issues and how to succeed (which in her eyes is a stable relationship, kids, marriage etc) – I enquired into her counsellor’s situation. No kids, no husband, 3 cats and uses the term “red flags” a lot.

She might have the best of intentions for my friend but it’s not who I would choose.

For people with crippling anxiety, offering them a group mental health power point session (as I received) on the NHS, is tantamount to malpractice, I always leave GP sessions feeling completely ignored and worse than before I go in.

The PHA was set up to build an alternative healthcare system as the NHS is failing too many folk.

I’m a practical soul, expressing sincere emotions is supportive but doesn’t address ongoing issues & deal with the root of the problem.

I hope you get the support you need.

Repeating my other comment here because it was meant to address just that:

Do not trust professionals paid to be nice to you. Chances are that they really think you’re a hell of a useless nuisance and start making jokes about you once you’re again past their door.

This doesn’t mean they’re evil or something like that or that their efforts are necessarily useless[*] but just that they’re humans working in a certain job, ultimatively, because they need to pay their bills, and that you’re a customer of them. They’re not your friends and they may become outright hostile should they happen to be paid for that.

[*] I’m personally convinced that all of these talking therapies are worse than useless for both anxiety and depression, something I’m quite familiar with. But these are just my prejudices stemming from a few negative experiences and I don’t claim to have any expertise on the topic.

not too surprised since they lie all the time, can’t trust them, glad you pointed that out to us ,no more masks! good for you for refusing!

Hi Whoshotjr really do feel for you. Well done for writing this article. Think you’re very brave in all you’ve done, keep up the good work and glad you’re getting better. As my old man used to say “don’t let the buggers get you down!”

Hi, yes that’s me 🙂 Your concern for me is very touching. I’m actually doing a lot better of late.

The support I had from everyone in the comments here actually moved me to make contact with my local Stand In The Park where I’ve befriended some absolutely lovely amazing people, it’s given me so much strength, I only wish I’d done it sooner!

Hurray!!!😀😊 Well i am chuffed you’ve popped back to check in with us, I am suitably relieved now.😁 And it’s great to hear you took the plunge in getting out with the SITP peeps. Congrats on getting your article published on here too.👍 Nice one! I hope life treats you better from here on in, you’ve made great inroads and significant progress all round.😇

Thankyou 😊 Although it’s been healing to speak to like minded people online I don’t think you can underestimate the importance of face to face socialising for mental wellbeing (definitely something the past three years has taught us!).

Hear hear 😁

As a private individual, my understanding of the affair was that in this case, “exemption” did not require a third party grant, or any issue to one. It was possible to unilaterally declare it, and download the official paperwork from a Gov website, then print it all out. Anyone trying to inquire as to why would be at pain of being outside the HR Act 1998, and other things.

Although it was likely that one did not actually need to wear some kind of badge to declare it, I did for a while. There was only one occasion when someone grumbled about it, and when I said I was and dangled it at her, she backed off. In short, a lot of it was a scam, but revealed the attitude of certain people, some of whom you evidently came across, for whatever reason.

I hope you are coping well with your difficulties now.

I was discussing this with a colleague today.

When government mandates were officially in place, so were exemptions. Now that there aren’t mandates in place and it isn’t government rules/guidance, do the exemptions still carry any weight to individual trust rules?

Any non pharmaceutical intervention ie a mask, alcohol gel is a medical intervention for which your informed consent is required. If you do not consent to a medical intervention, by law you cannot be coerced into receiving or using that NPI. All healthcare is dispensed based on informed consent. Without consent it cannot be carried out. Not consenting to intervention x does not exempt one from accessing intervention y. By placing the crowd first in healthcare they have inverted the whole principle on which healthcare is based.

Readers should watch the ultimate masks evidence video compled by Ivor Cummings.

Just watched it. A veritable sackful of reverse ferrets. Despicable!

And there are some excellent videos by Stephen Petty:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J3dnkbKoj4A

Stephen Petty – On the effectiveness of masks

So very sorry your life over the last three years became a nightmare. Beyond maddening that it didn’t have to be that way. Yes, were medical professionals always so inhumane but could easily cover it up with easy smiles and comforting words? Or did government propaganda–perfected through psychological research–turn even the most compassionate people into monsters?

One of the worst aspects of this for me is that one of the people responsible for making the decision to do this to me is a former therapist of mine.

I trusted this man completely, knew him for years, I told him everything about myself. I showed him my most vulnerable parts, bared my soul to him. Then this. It shook me to my core.

I asked myself repeatedly; Is this who he always was? Or who he has become? I don’t know which is more disturbing.

That must hurt a lot. Although I’ve never used mental health services my trust in the medical profession as a whole has been severely damaged. If they seriously believe these face rags are effective and necessary, how can their scientific opinion be anything other than worthless?

I’m sorry you have been abused in this way.

I felt the same and experienced similar although not as severe.

In the middle of it all I needed breathing checks and refused masks, was suicidal and in pieces in front of a GP, who I had to beg to be seen in person by, only to face a battle for the first half of the appointment, the receptionist and the asthma nurse over my lack of face covering. I eventually asked the GP are you going to treat me as you are legally required to or not and explained I didn’t wish to spend the 2nd half of my appointment arguing about ineffective nonsense.

I was ready to walk into traffic that day and get extremely anxious about hospitals now. I couldn’t visit dad who was in for 3 days recently due to the anxiety, I live with high levels but confrontation takes it up a few notches (a reason I’ve un-subbed London Calling).

Now I’ve been stuck with chest pains and concerns for my heart for a few weeks, but can’t bring myself to deal with the NHS.

They always were f’ing useless but Covid brought them up to a whole new level.

me too i didn’t go to the dr for months all because i despise so much the idiotic masks. i blame it all on the masks , lockdown, and’vax’ passports and am still angry about it all not to mention family and friends treating me like leper and still wont admit they were wrong or apologize for it all.

can you try deep breaths and going for walks out of doors, i used to g et chest pains

and pretty sure just was stress

makes me so angry what they have done to us.

I don’t think you should ignore chest pains. Try to find a doctor who will see you without masks.

Thanks both

I’ve made some changes, healthy eating and trying to relax. Due to leg issues I can’t really exercise but I did manage to see a physio least week so that’s progress – he was of course wearing a mask. When I said not to on my account he said “oh ok, but I’ve been ill the last few days, but it’s not covid” before pulling it down under his chin. You couldn’t make it up, if you’re sick stay home, if your not take off the placebo!

As for the chest, I have so little trust in Drs now, if it’s serious (heart disease etc) then I’m screwed anyways, if it’s fixable with lifestyle changes, then that’s where I’m focussing already.

I second what sam s.j. wrote: I had to deal with a lot of errant pain, mostly mild but some very serious, including chest pains, during the so-called pandemice, ie, the heyday of pandemic policies. I’m convinced that this was all cramps and micro-cramps and they’ve all gone all but away by sticking to a routine of lengthy walks in the fresh air in calm places (ie, places without loads of stressed people).

I don’t know who is responsible for pushing the mask madness once again but if I have to use NHS services I will politely demand to be seen by non mask wearing staff. If that is refused then I will have to leave and do the best I can myself.

Those people who work in healthcare and still insist on masks should be dismissed on the spot because they decidedly DO NOT have any understanding of basic medicine. The reality is that such people are a danger to the public as much as themselves.

The fact that the fat Tory minister has not stepped in to put a stop to this witchcraft shows exactly who is driving the policy.

And before anyone states that this has nothing to do with government I will point out that neither did the numbers of people I had in my house during lockdowns, or how far I travelled etc. etc.

I was contacted by GP practice to attend for cancer test. When I explained I was mask exempt they refused to see me. My hubby, a lawyer, emailed head GP mentioned discrimination, medical negligence – and I was allowed in, through back door, at lunch time when no one around and with neg LFT. Nurse asked me to hold my breath as I walked down corridor to consulting room, where I was once again allowed to breath. These people are supposed to be medical professionals.

glad your hubby got after them and won

they are insane

i had a dr chase me down the hall as i was leaving. i had lied the first visit when she asked if i got the so called vaccine[ she left out ‘so called’], i didn’t wear a mask, maybe she wasn’t wearing one i forget now,

the next visit i mentioned that actually i did not get the ‘ shot ‘ and she immediately put on her mask and a visor , i forget what else, and hustled me out the door running after me trying unsuccessfully to g et me to put on a mask.s till makes me laugh but am still angry too about the whole insane last 3 years.

I feel as though I’ve stepped into 2021 by mistake! The last time I saw a practitioner at our surgery was for a blood test 6 months ago and not a mask was in sight. No one in that surgery wears masks any more. The same at my dentist where masks were done away with, along with all other covid measures, at the earliest opportunity. In fact, the only people I see always wearing masks these days are the staff in the Tesco chemist (but not the high Street chemist in our nearest town). Fortunately I don’t have to frequent local hospitals, but I was pleased to see that the o.a.p. home where I visit a friend is totally back to normal too. There seems to be so much variation across the country, but I am sure our area is not alone in seeming to have forgotten all about covid.

Unbelievable.

I am properly revved up for a serious row the next time I have to deal with NHS idiots.

I was forced to wear a mask for an MRI scan at a private hospital during the main part of the pandemic measures, despite claiming exemption. I was told, ‘no mask, no MRI’. I was surprised how agitated this made me feel. It wasn’t a pleasant experience.

I ended up avoiding shops entirely for a long time due to the mask requirements, as I harted them, until I basically thought ‘bother that’ (I may have used a slightly stronger word!) and just started going again maskless. I did carry an exemption pass as I found like a crucifix warning off vampires it was effective at stopping staff even asking for a mask.

Even now my wife finds that some NHS hospitals are requiring masks – despite the evidence showing they are worse than useless – and has to keep telling them she’s exempt.

Contrast that to the private hospital where I had the mask issue originally, where they are now entirely optional and hardly anyone is wearing them.

Maskholes are indistinguishable from the deeply religious, aren’t they?

🤣🤣 “Maskholes”! Yes I really can’t get over the stories I hear about the state of the medical establishment regarding masks in the UK. The whole lot of them seem to have lost the plot. I think they should be thoroughly ashamed, especially given the industry they work in and professions they represent. It does sound entirely like a cult, so not remotely based on the latest scientific evidence then. Bloody masktards!😷🧟♂️ The biggest laugh will be that it’s this lot who’ll be gene therapied to the max, yet they fail to see just how contradictory and irrational their behaviour is! Imagine being on jab number 5 or 6 but still wearing your magic talisman face nappy?!! They ought to just get lobotomized and have done.🤦♂️

“Maskholes” – absolutely brilliant 👍🤣

“…yet I have asked myself many times why people working in a ‘caring profession’ and who profess to be scientific in their approach should act with so little feeling and so little logic.”

That is a key point right there. As science is supposed to be a discipline, or a collection of methods to create empirical knowledge, it appears that science has actually been abandoned. Therefore what is the quality of any decision or analysis made by these medically trained professionals as they should be acting in the interest of the patient and not following any central diktats?

Something important to take away from this (and from earlier articles written by the woman with the autistic child being mistreated at school):

Do not trust professionals paid to be nice to you. Chances are that they really think you’re a hell of a useless nuisance and start making jokes about you once you’re again past their door.

The writer says: ‘At home I watched morning TV and heard so-called ‘celebrities’ declare that “people who don’t wear face masks should be in the stocks, in prison, or hanging in the streets” Who said this?

EDIT – that’s interesting. As my comment published itself it gave me a link to the person who did say this. Jason Isaacs, Harry Potter ‘star’.

Beyond despicable – left working in the NHS with disgust at the way patients and staff were treated who could not or would not wear a mask.I argued against their use with senior management who had no riposte to my arguments and would either just look blankly at me or bleat out the same old sophist mantra about keeping people safe.

I stood up to the nonsense and however much I was threatened just ignored them and continued to argue my case. With the threat of vaccine mandates I decided to start my own private practice. Took a while, but now when I see a patient, no masking and face to face.

Masks are symbolic of madness and are fundamentally degrading and dehumanising. I supported a client to hospital the other day and over heard a nurse complaining about wearing them. Well take the stupid thing off I said. You do realize that there is no evidence base to support wearing them and they were only mandated to promote fear. Explained about SPI-B etc. Show some courage or just be crushed. She slithered off looking sheepish and afraid.

Where does the ultimate blame for this cruelty lie? From the Government to the WHO etc. as we well know. The present so called Government could end much of this pernicious nonsense yesterday. Simply admit that the things do nothing (other than harm) and should not have been mandated. Of course the venal creatures will not.

My heart goes out to you and I wish you well on your road to recovery.

I have a serious health condition, it used to be an “underlying” one, but due to the effects of lockdown (gyms being closed, for example) and the obscene amounts of stress 2020, 2021 caused me personally, it became what it is now; life threatening.

Long story, short, I’m now in the process of being evaluated for major, life altering surgery, part of which process involved me having to attend the hospital for a series of tests. Despite the hospital boldly featuring posters claiming that it recognises “the sunflower” (the sunflower lanyards) and stating that “masks are recommended”), the staff’s behaviour around masks was absolutely disgusting.

Putting aside the fact that the letters and phone calls advising of appointments are 90% about Covid and Covid symptoms, with scant information on what to expect when you arrive, when I got to the departments that were carrying out the tests, I had to report to the reception desks, which featured a mask wearing receptionist who, after asking several questions regarding my “Covid-status”, and despite seeing my sunflower lanyard, asked if I was able to wear a mask.

Here’s the thing. The only reason I’d even be attending these departments is because I have a serious health condition which, even during the days of mask mandates would have excepted me from wearing one. Yet you’re still asked if you can wear one. Bear in mind that all the staff are wearing them and will absolutely be double-triple-quadruple-jabbed. But yeah, I better exacerbate my health condition by wearing one, right?

They don’t seem to realise how stressful, dismissive and demoralising it is to say “no”, followed by the pregnant pause where you’re supposed to justify yourself.

I realise this may sound weird, but due to my personality type, I want to reply “you do realise why I’m here, don’t you? So, obviously the answer is no”.

Upon entry to the rooms where the tests were to be carried out, on both occasions the first question I was asked was “can you wear a mask?”.

The first time I responded “I have [insert health condition], so, no.”

The response? “So if you want to just get up on the table…” No acknowledgment of my reason, no attempt to ally the social awkwardness of being the weird outlier who doesn’t comply.

No attempt to make you feel at ease and diffuse the stress. No empathy for the feelings of deep despair and worry you’re experiencing at having to need this particular test which is likely to show your condition is as bad as the surgeons and consultants fear it is.

The second time I was lying stripped to the waist on an examination table waiting for the technician. She arrived and, again, the first question is “can you wear a mask?”.

This time I replied “no.”

She just looked at me. She’s wearing a mask. She’s expecting more information from me as to why I can’t wear mask. Again, the one and only reason I’d be presenting myself on her examination table is the reason why I can’t wear a mask. Did she want me to spell it out? I’d already used up my one and only “I’ll spell out the health condition that excepts me from wearing a mask”.

She’s obviously waiting for me to say something else. “I mean, I’ve got an exception lanyard, but”, I gesture to my naked torso, “I can’t wear it just now but I can go and get it out my jacket pocket if that helps.” I’m moving into a defensive, sarcastic frame of mind, which considering where I am and why I’m there, I didn’t want to do.

She turned away from me, looked at her testing equipment’s screen and said, “ok, so if you just want to turn over onto your left side”.

The whole experience made me realising that the NHS has reduced all of its staff to no longer seeing its “customers” as people, but rather as binary “mask on/mask off” blobs.

Conversely, when I went to see the surgeon (who ended up telling me my condition is likely to be inoperable), while he wore a mask in the reception area, immediately took it off in his consultation room and didn’t once query as to whether I could wear one.

Why not? Likely because he’s smart enough to realise that the reason I was even meeting with him in the first was much more grave and life-threatening than any risk of a respiratory virus that a mask wouldn’t prevent anyway.

It seems the vast majority of me working on ‘the caring profession’ were “fully absorbed into the Covidian sect created by the Government’s propaganda and manipulation” and just didn’t care. In the phrase from the comedy film ‘Hot Fuzz’, the “greater good” just doesn’t give a damn about the individual.

Be strong, there are a significant and growing number who are awake to the Govt’s evil mendacity at the whole covid response mendacity. You are right, they are wrong. Never forget that.

St Helens walk in centre refused to treat me because of my ‘mask exemption’ despite my arm going septic following surgery. I still find it incredible that so many ‘medical professionals’ dumped their medical knowledge and training in an instant on the basis of ‘keeping ourselves safe and protecting others’ mantra.

I complained. The lead medic that day must have known they were in breach of the law (I had pointed this out to them) so instead made a note (a complete lie) that she had tried to treat but that I was aggressive. The Trust advised that they would not investigate further than the basic initial complaints process because ‘no significant harm had resulted’. Well that was only because my husband drove me to A&E and insisted I get treated there instead of my preferred option of going home.

So, a whole day in pain instead of a couple of hours and marked down on the system as being ‘aggressive’ and naff all you can do

“I am the one who, because of my conditions, is supposed to be irrational;”

When it comes to the imposition of masks we all know who were/are the irrational ones.

Dear Anon,

I’m so sorry to hear of the hypocritical and abusive responses you have received from Mersey Health Care. How the hell they can have an “Ethical Cells Committee” is beyond me; they cannot begin to understand the meaning of the word ‘ethics’. Obviously ‘our NHS’ is the “envy of the world” because ‘our’ snowflake health care professionals feel free to abuse vulnerable patients on the basis of zero clinical or empirical evidence. They are disgusting and shouldn’t be allowed anywhere near people who need their support. I hope that all the support you receive on here will provide you some comfort and my very best wishes for your future. ” Illegitimi non carborundum” 👍