Escherichia coli – E. coli for short – is a bacterium with two faces. Some strains produce toxins that cause gastrointestinal disease. Set these aside. We’re concerned with the other strains that live innocuously in the colon. They’re among the most abundant gut bacteria and only cause trouble if they reach other body sites.

This happens if the gut contents leak during surgery, for example, or via a ruptured appendix. More commonly, particularly in women, gut E. coli reach the urinary tract and swim upwards, causing UTIs (urinary tract infections). Some strains are especially adept swimmers; five or six ‘uropathogenic’ lineages account for half of all UTIs.

In total, E. coli causes 80% of all UTIs, with 150 million cases annually worldwide. Most are painful but self-limiting ‘cystitis’, reaching no higher than the bladder. These used to be treated with trimethoprim. Nowadays, owing to trimethoprim resistance, nitrofurantoin is preferred. A few reach the kidneys and, worse, then spill into the bloodstream. That’s bacteraemia – bacteria in the blood – which can trigger life-threatening sepsis.

E. coli accounted for a third of all U.K. bacteraemias in fiscal year 2019-20, with a tally of 43,395 cases, mostly in the elderly. Hospitals in England are obliged to report these, so numbers should be robust. UTI ‘overspill’ accounts for at least half; gut leakage for a quarter. Most UTI-origin cases develop in the community and enter hospital through A&E.

Around 18% of E. coli bacteraemia patients die in the U.K. This rate roughly doubles if treatment is inadequate, usually because the E. coli strain was resistant to the first antibiotic given. (The patient must be treated immediately but it takes two days for the lab to get results, creating a window for error.) Mortality must be similarly high among untreated bacteraemias. Keefer, at the end of the pre-antibiotic era, found 35% deaths.

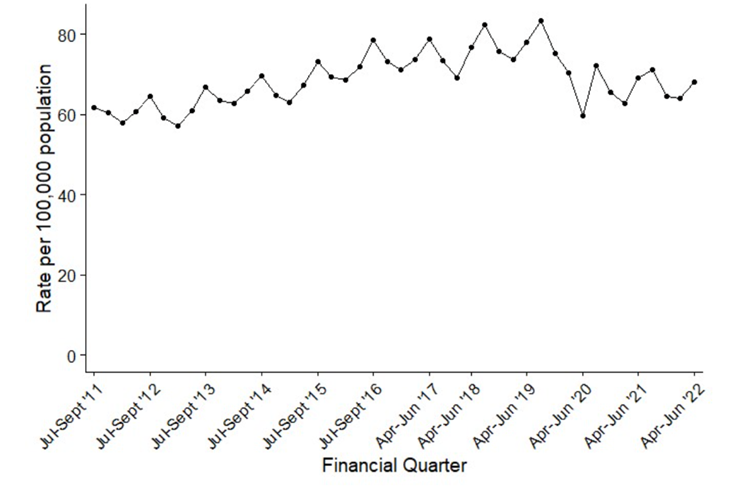

Right, that’s the background. Now, look at case incidence for England (figure 1). Three points stand out: 1) a long upward trend to 2019-20; 2) summer peaks, never properly explained and 3) a big step down at the start of the Covid pandemic. It hasn’t gone up again.

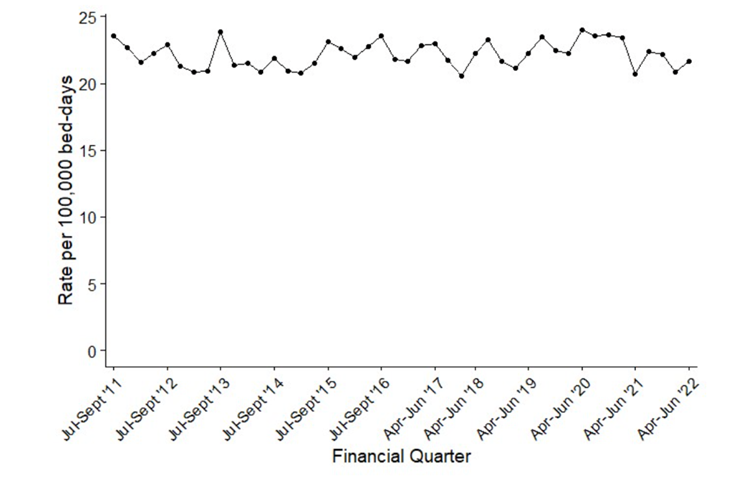

This step isn’t apparent – with a caveat below – for the subset of hospital-onset E. coli bacteraemias (figure 2), or for Klebsiella (not shown), which is related to E. coli, but is largely a nosocomial (hospital-caught) pathogen.

Why?

Five possible explanations can be dismissed:

- COVID restrictions suppressed them. This lacks plausibility. E. coli bacteraemias involve the patient’s own gut flora. Lockdowns, social distancing, masks etc. don’t alter proximity to our own gut. Moreover, case numbers didn’t rebound after restrictions eased over a year ago.

- A denominator issue. This is unlikely for figure 1, where rates are expressed per 100,000 population, and a delve into the raw numbers (table below) shows exactly the same pattern. There is an issue for figure 2’s hospital-onset cases, which are reported per 100,000 occupied bed days. Here, the raw case numbers are flat from 2012/13 to 2019/20, with a 16% drop in 2020/21 and a partial rebound in 2021/22, perhaps reflecting a different case mix through the pandemic or altered hospital occupancy. Hospital-onset cases are often gut-surgery-related, not urinary.

- Hospitals are failing to report cases. This can’t be wholly dismissed. But, were it the major factor, one would expect the tally of community-onset cases to show the same rebound in 2021-22 as for hospital-onset cases. It doesn’t. What is more, reported Klebsiella bacteraemias rose continuously to 2021-22.

- SARS-CoV-2 killed the patients who develop E. coli bacteraemias. Some erstwhile PHE colleagues believed this in 2020, and it may be part of the story. But Covid deaths are fewer now, and new people are reaching decrepitude, making them vulnerable to E. coli. So, numbers should have bounced back, but haven’t.

- The change from trimethoprim to nitrofurantoin reduced the number of UTIs progressing to bacteraemia. It would be nice if this was true, but it isn’t. The switch in prescribing was progressive, largely from 2016 to early 2019. It can’t explain a much later and steeper fall in bacteraemias.

So, we’re left with the likely explanation: that community patients whose UTIs ‘go bad’, leading to potentially fatal bacteraemia, aren’t presenting at A&E. Maybe they are not even receiving treatment for the underlying UTIs in the first place. A drop of 60-70% in UTI diagnoses was asserted early in the pandemic, with only a partial ‘recovery’ by October 2020. Formal publication and extension of these important data is still awaited.

Next, consider two strands of anecdotal evidence. First, Carl Heneghan stresses how easily a UTI is missed in 92-year-old Mrs Jones who – as so often with the very elderly – lacks typical symptoms. Rather, she “is a little confused and a bit wobbly on her feet, though all her observations are normal”.

She’d be even harder to diagnose via a telephone consultation, should she be able to book one. Which brings us, secondly, to the ex-wife of a prominent Cabinet Minister calling her GP apropos a respiratory tract infection.

After 47 attempts to get past the ‘engaged’ tone (my phone logged them), I finally got through to a recorded message about how busy they were, and I was placed in a queue. I actually felt grateful.

I waited a further 40 minutes before the receptionist finally answered, only to be told – you guessed it – that no appointments were available.

On Tuesday, the infection was much worse. I tried again. This time it took 45 minutes to get through. Again, no appointments were available. The receptionist suggested emailing.

It’d be no easier for a UTI. And it’d be harder if, unlike Sarah Vine, you are 92 years old, a little confused and wobbly on your feet. It’d be tempting to give up. Numerous missed UTIs and consequent community-onset bacteraemia seem very likely.

As has been widely flagged, the U.K. is persistently recording 10-15% excess mortality. Unusually large numbers of deaths are occurring at home. My view is that these deaths overwhelmingly comprise groups who didn’t or couldn’t access medical attention over the past two and a half years. At present cardiac deaths are prominent. Still to come is a large slab of deaths from cancers that would have been treatable had they been diagnosed in 2020, but which were diagnosed late.

But somewhere, hidden among the total, is a slice of my missing community-onset E. coli bacteraemias. A mortality rate of 35%, as in the pre-antibiotic era, would predict 1,750 deaths among missing 5,000 patients, half of them preventable with adequate antibiotics. So, a little under a thousand annually. But, it’ll be significantly higher if, as is very likely, more untreated ascending UTIs has led to more undetected bacteraemias than before the pandemic.

Dr. David Livermore is Professor of Medical Microbiology at the University of East Anglia.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Emails suggest ex-NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo launched COVID-19 memoir project in March 2020”

Well, well, well…

Sing: What a bunch of fecking Eejits!

What a bunch of fecking Eejits!

“We are trans and cis together”

Vomit inducing nonsense…

For the non local Norwich City Council has been Labour controlled for years .These tools do not represent the good people of Norfolk in the main .

Their local electorate are skewed by three huge public housing areas plus the University. Am I surprised ? No not really lol

“Labour council staff take the knee prompting row with Salford residents”

Another group of public servants mistaking their misplaced sense of compassion for the green light to ignore their duty to the people who pay their wages..

Mr Floyd didn’t really deserve a lot of compassion really, and the whole BLM movement has proven to be ‘scam whitey’, but there you go..

F-me, their not still taking the knee are they?

That’s so yesterday!

The picture in that link makes me

Someone please, help them to their feet, dust them off ,wash their clothes and give them a good meal! Their so lost and needy bless them, it makes me tear up ! Chunts

up ! Chunts

The need to stop the WHO’s pandemic treaty and IHR amendments is getting more urgent by the minute.

Yesterday, the WHO appointed North Korea to its executive committee.

You could not make it up.

What could possibly go wrong?

Does anyone else feel the transition to Clown World is accelerating?

Hell yes, we all feel it! and its terrifying!

Just to add, I seriously feel the pain and frustration you do! This “new dawn” is frightening all of us who still possess our own brains!

Prof Kathleen Stock has written about her Oxford talk. *Spoiler* It was an all-round positive experience.

”Other supportive students in Oxford, neither feminist nor anti-feminist, just seemed fed up with being emotionally blackmailed into stifled silence by a small group of childish and histrionic narcissists — among which they doubtless would include the occasional lecturer. And from within each Union, the committee members responsible for inviting me were totally impressive, standing resolute against pressure and showing exemplary resilience in the face of harsh criticism from some peers.

In looking at some of the media coverage of my Oxford trip, it’s striking to me that certain journalists’ idea of balanced reporting is to interview, on one hand, Stock the supposedly offensive speaker, and on the other, students who say they feel threatened and frightened by my terrifying words. (The rough format goes as follows. Student: “I just feel exhausted constantly having to justify my existence every day!”. Interviewer: “What do you, Stock, say to the students who feel exhausted having to justify their existence every day?” Me, looking at said students, apparently with enough energy to drum and chant for hours: “Erm … I’m not sure. Maybe get their iron levels checked?”.)”

https://unherd.com/2023/06/the-oxford-kids-are-alright/

The recent World Health Assembly singles out Israel as a ”violator of human rights” and in true back to front, Clown World fashion, North Korea have the nerve to say this…

And check out the other countries condemning them. What a joke!

”North Korea, which was just elected to a 3-year term on on the WHO executive board, said it was “deeply concerned about the health conditions in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The prolonged occupation, illegal settlement activity, and discriminatory practices continue to negatively impact the living conditions of the population.”

https://unwatch.org/whos-2023-assembly-once-again-singles-out-israel-as-violator-of-health-rights/

That is classic. North Korea of course known for respecting the health conditions and ensuring no discriminatory practices of its own population. Alarmingly, North Korea get a seat on the board of the WHO…what on earth could go wrong with that?

Mogs, your the fount of all knowledge! Can you run for prime minister/president in all countries? Your wisdom is so needed right now

Well I don’t know about that, but I feel ready to achieve my PhD in ‘Cutting and Pasting’.

Bless you, your a gem!

I wish I had your integrity

That’s sweet of you to say Dinger. Kids holidays over here so got more down time..

Kids holidays over here so got more down time..

..while I agree with you that it’s hypocritical..I also think, that in relation to Palestine, it’s not entirely wrong either.

If you read the article you note that the ‘’spokesperson’ they feature is from UN Watch..which is supposedly an independent NGO, but which has very strong financial ties with the American Jewish Committee… they mention Syria..but only in relation to Russia bombing it (over three years ago)..they don’t mention the current illegal occupation of the USA in Syria, nor the USA’s theft of their oil and grain, nor do they mention the stringent US sanctions that are crippling Syria, nor the constant bombing raids by Israel….they mention Afghanistan, but again no mention of the USA’s occupation, or sanctions, nor the fact that they stole and still refuse to release millions of dollars of Afghani money.

I’m not particularly trying to pick a side here, and I’m not anti-Israel…. but the West doesn’t allow ‘the rest’ a platform in general…and I’m not convinced they get a fair deal when it comes to battling against the might that is the USA and the West’s established constructs. There are real global changes happening in the world, as we can all see..I think they need to be addressed in a different way than just saying one set is always right, while one set is always wrong?!

Yes, I agree. Not defending Israel. Just the hypocrisy and sheer nerve of countries such Iran and N. Korea finger-wagging about mistreatment of citizenry elsewhere. Plus to highlight the fact N. Korea were actually *elected* by the WHO. I mean, as if we need further confirmation of just how big a criminal outfit and significant threat to democracy they are. But leaders in the West will sign over our sovereignty in a nanosecond regardless.

And it got picked up ATL, in record time..LOL!!

“We are trans and cis together” – new religion?

Remember also how some churches flew flags saying “thank you NHS”? That was like a new religion too.

As for “memory loss during lockdowns”: it’s what the tyranny is hoping for, that people will erase it from their minds, as if it never happened, and they will forgive the politicians in time for the next election, and the next plandemic (which the tyrants seem certain will happen). I have no intention of forgetting anything, from the locked playgrounds, to children locked in their homes behind their rainbows, to the “be a superhero” coercion to mask up and roll up your sleeve, and we must remind Parliament about these deeds on a regular basis. They must never be forgiven or forgotten.

Labour party members in parliament worked with Conservatives in drafting the Coronavirus Bill 2000. Both houses of parliament passed the Coronavirus Act 2000 without division. The Scottish parliament gave formal Consent to the UK-wide legislation without a vote on it.

Scum, the lot of them.

Agreed

Bang on! Here no,see no,say no! “Don’t mention the war, ….sorry…. vaccines!”

When the long sinuses blood clots stretch through their veins they may want an answer all of a sudden!

Seconded.

The FDA have just approved the new Pfizer RSV jab for 60+ year old, but if there’s one thing we’ve learnt ( we critical thinkers have learnt a lot, of course ) it’s that these claims of efficacy are totally bogus and not what they are widely touted in the media.

https://twitter.com/ITGuy1959/status/1664086303401558020

Placebos in medical trials have been eliminated & RRR used instead of ARR… Talk about gaming the system to achieve the desired outcome.

Rrr? Arr? Sorry I’m a bit thick, please explain

Relative Risk Reduction vs Actual Risk Reduction

RRR always gives a higher % than ARR thus making the product seem more effective. The covid injections we were told gave 95% protection. Dig down into the data & that was the difference between the ‘product’ & the placebo. Translate that into ARR & you get less than 1% ie not worth a damned thing!

All smoke & mirrors to dupe a population which is basically numerically illiterate.

Not thick, learning. We’re all learning on a daily basis.

Hope that this clarifies things for you

BB

…I still have a look at this short video every so often to remind me!!

For some reason it just won’t stick in my head!

Proff Norman Fenton….explaining relative risk v actual risk….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQlBZUc4Ao8

Andrea Jenkins should not display her inadequacy. What could the civil servants do if she arranged to meet in the nearest Spoons for a refillable coffee at £1.70 each.

“Climate protester left with block of tarmac stuck to his hand is jailed”

Leave him like that! Twat

Novak Djokovic almost always cheers me up. He’s annoying the French Minister for Sport, who one imagines is a good person to annoy: French Open 2023: Novak Djokovic stands by Kosovo message after criticism – BBC Sport

French sports minister Amelie Oudea-Castera said there needs to be a “principle of neutrality for the field of play”.

Oudea-Castera said she made a distinction for messages in support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s invasion, adding that she did not put Kosovo and Ukraine “on the same level”.

So a nice bit of the usual Western hypocrisy then? It’s ‘neutral’ to be against Russia..but not Kosovo…do these people ever listen to themselves…??

Tennis community was happy for some players to express support for BLM…

““Black people were three times more likely to receive Covid fines in England and Wales” – Those in poorest areas were seven times more likely to be fined, finds research into how police used emergency powers, says the Guardian. Are these the first signs of remorse from the pro-lockdown paper?”

Of course not. It’ll be some “anti-racist” nonsense. If you were against lockdowns, why would you care who it affected most – surely you’re against them for everyone? It reminds me of an exchange I had with an acquaintance mine, early on in proceedings. He’s a senior manager in the NHS. One of the reasons he gave that we should lock down and take covid seriously was that it disproportionately affected non-white people.

Of course it disproportionately affected folk with darker skin – their Vit D serum levels were through the floor & adequate Vit D levels reduced the severity of said illness & risk of being subjected to the death protocols in hospitals.

If only the data from the frontline medics had been utilised rather than censored….

But the government does have your best interests at heart…. Honestly….

Damn! that battalion of flying pigs has just crashed in flames…

What.? With all those multi-generational houses,and a tendency to spend their evenings in the streets with friends and neighbours, or praying five times a day.

“Electric car infrastructure creaks under demand”

So of your not well off enough to have a house you own, a private drive ,30 plus grand lying around in the first place, not to mention a caravan, a boat, a trailer, nowhere you need to go! Retired, solar panels and a healthy bank balance! Electric cars are just the thing for you! (About 5% of the population at best) I think evs have reached all the customers they are ever going to reach! It always was a niche product!

“Covid lockdown may have created similar memory problems to those that people who are locked up in prions”

Freudian slip?

Nice one

Meanwhile!: “BGT’s Amanda Holden glitters in sheer gown with sizzling thigh split”

Look over here! Oi, sheeple, here! (Click fingers loudly) Ignore the smoke and mirrors and the man behind the curtain!

‘The man behind the curtain’???

Although a bit rude about ‘her’ sheer gown it’s certainly the Amanda Holden story we might be bothered to read.

This is quite worrying….I haven’t seen this reported in any British media (naturally)…..when you remember that we live in a country that still keeps reporter Julian Assange in prison..and that only a couple of weeks ago was defending a US reporter detained by Russia….

“Britain has called for the release of a US journalist detained in Moscow.

No10 said Rishi Sunak stood ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with the US over its efforts to free Evan Gershkovich.”

https://thegrayzone.com/2023/05/30/journalist-kit-klarenberg-british-police-interrogated-grayzone/

British counter-terror police detained journalist Kit Klarenberg upon his arrival at London’s Luton airport and subjected him to an extended interrogation about his political views and reporting for The Grayzone.As soon as journalist Kit Klarenberg landed in his home country of Britain on May 17, 2023, six anonymous plainclothes counter-terror officers detained him. They quickly escorted him to a back room, where they grilled him for over five hours about his reporting for this outlet. They also inquired about his personal opinion on everything from the current British political leadership to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

….During Klarenberg’s detention, police seized the journalist’s electronic devices and SD cards, fingerprinted him, took DNA swabs, and photographed him intensively. They threatened to arrest him if he did not comply.