Almost all scientific papers go through something called ‘peer review’ before they’re published.

This usually works as follows: the paper is sent to a scientific journal; the editor of that journal selects two or three reviewers whom he or she considers experts in the relevant subject matter; each reviewer reads the paper and submits a report indicating whether it should be accepted, rejected or revised; the editor then makes a decision based the reviewers’ reports.

Most journals use ‘double blind’ reviewing, where the reviewers don’t know the identity of the authors, and the authors don’t know the identity of the reviewers. Some journals use ‘single blind’ reviewing, where the reviewers know the identity of the authors, or vice versa. And a small number of journals use ‘open peer review’, where everyone’s identity is known to everyone else.

Even when journals use double blind reviewing, it is often still possible for reviewers to work out who the authors are. The latter may have already may have presented the paper at a conference or published a ‘preprint’ online. Sometimes it is possible to work out who the authors purely from the content of the paper (e.g., because it builds on previous research they have done).

In an ideal world, reviewers’ recommendations would be based solely on objective criteria, like the suitability of the research design and the absence of errors in analysis. Yet evidence (and the personal experience of many academics) suggests this is rarely the case. Various forms of bias afflict the reviewing process.

In a new paper (which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed!) Juergen Huber and colleagues explore one particular form of bias: ‘status bias’. Are reviewers more likely to recommend ‘revise’ or ‘accept when the authors are big names in the field than when they’re complete nobodies?

Huber and colleagues carried out a field experiment, working with the editor of a major economics journal. A paper was submitted to the journal which had two authors: one a Nobel Prize winner in economics, the other an unknown research associate. Like the journal’s editor, they were both ‘in on’ the study.

The paper was then sent out to 3,300 potential reviewers, in order to get a large enough sample size. There were three different treatments.

In treatment ‘AL’, the unknown research associate was given as the paper’s corresponding author (so this was single blind). In ‘AA’, no corresponding author was given (so this was double blind). And in ‘AH’, the Nobel Prize winner was given as the corresponding author (this was single blind again).

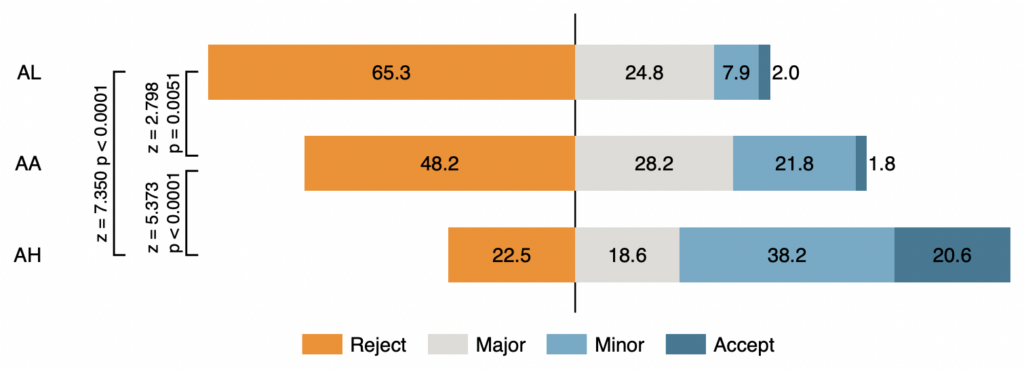

Huber and colleagues’ main result is shown in the chart below. Each coloured bar represents the distribution of reviewers’ recommendations in a particular treatment.

As you can see, reviewers were far more likely to say the paper should be rejected when the unknown research associate was given as the corresponding author. In ‘AL’, 65% of reviewers recommended ‘reject’, compared to only 23% in ‘AH’. So you’re about one third as likely to have your paper rejected if you’re a Nobel Prize winner.

Needless to say, this isn’t how science is meant to work. Rather than judging papers on their own merits, most reviewers are content to employ heuristics like “work by a Nobel Prize winner must be good” or, indeed, “work by an unknown research associate must be bad”.

The pandemic showed what can happen when defer too much to credentialed ‘experts’. And it’s not just politicians and laypeople that fall into this traps – so do scientists themselves.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“In February 1616, the Inquisition assembled a committee of theologians, known as qualifiers, who delivered their unanimous report condemning heliocentrism as “foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture.” Wikipedia

I note that it was only relatively recently (1822) that the Catholic Church removed works proposing heliocentrism from its Index of Forbidden Books. But has it ever actually accepted heliocentrism?

The problem is as old as the hills…

Visited Toruń, Poland two weeks ago. Copernicus was a very brave, intelligent, humble chap.

It was not until 1992 I think that the Church finally officially admitted that Galileo was right all along.

Pal review is more like it.