In the short time available between the Depp-Heard case ending and the Queen’s Jubilee festivities starting I thought I’d have a quick look at some of the scientific papers recently published about the longer term consequences of Covid, with consequential impact on how scared we should be of the disease and what efforts might be effective in protecting ourselves. In this article I will look in-depth at one which considers the impact of vaccination, and in a follow-up article I will look at the other four.

The paper I’m looking at in this article is the one by Al-Aly et al., published in Nature on May 25th, titled “Long Covid after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection“. This compared outcomes after Covid infection of almost 35,000 vaccinated U.S. veterans with a set of control groups. To make it clear, ‘veterans’ aren’t, as a colleague of mine once thought, people that look after the health of animals, but instead are members of the U.S. armed forces after they finish active service. As a result, the study looks at individuals aged from approximately 40 to those in their 80s, and the group is biased towards males (though it does include many females).

It is important to note that the study looked at a wide variety of conditions that were present beyond 30 days after the individual’s positive test for Covid. Thus the data shown in the paper, and reproduced below, don’t include symptoms experienced during the actual acute disease stage of the infection, but they do include sequelae (disease after-effects) that started during the 30 days post-infection, but continued in the weeks and months after this point.

The results? In summary:

- Long Covid exists at a non-trivial level in those who had symptomatic disease that was serious enough to warrant seeking assistance from their healthcare providers.

- There are no useful data on the incidence of Long Covid in people that had mild Covid disease.

- There are no useful data on the protection offered by the vaccines.

- There is a strong suggestion that there are significant levels of vaccine injury in vaccinated individuals who weren’t infected with Covid.

- Rates of myocarditis appear to be very high in the group that included vaccine side-effects in the six months after vaccination (but where Covid infection occurred at least 30 days before vaccination).

Let’s take a closer look at the detail.

The study found a significant increase in sequelae in those having a breakthrough infection (i.e., infection after vaccination) compared with their control groups.

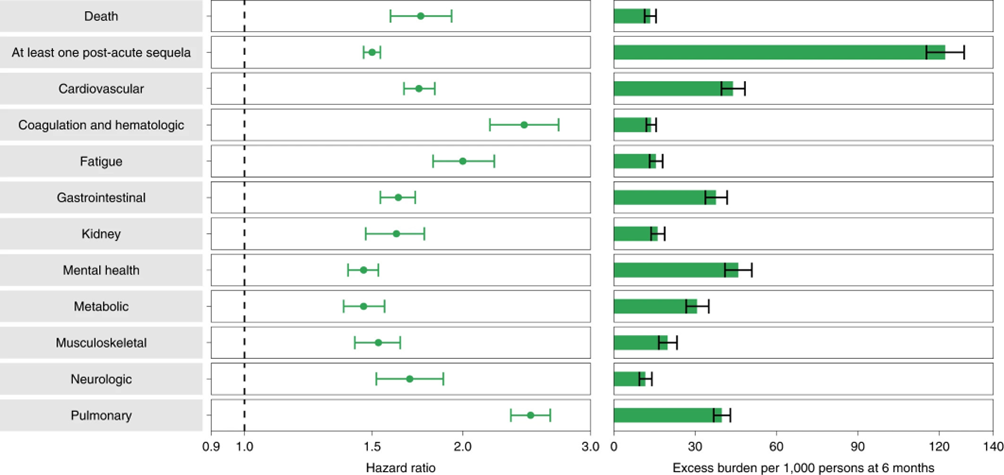

That’s a complicated graph, so a quick summary: On the left are ‘hazard ratios’, anything above 1.0 means that the study group (vaccinated infected) had more problems with their health (sequelae) than the control group (that didn’t get infected with Covid before or during the study period). For example, around about twice as many people in the vaccinated-infected group had problems with fatigue than in the control group (hazard ratio is about 2.0). On the right are the number of additional cases of each sub-type of sequelae that were seen, per 1,000 people – this is a very important aspect of the results, as it reflects the real-world impact of disease. The number of additional cases of ‘negative health conditions’ in the infected group was around 10-40 cases per 1,000 individuals for each sequelae category (i.e., an absolute increase in each category by around 1%-4%).

On the face of it that’s a rather scary graph – it suggests that around 12% of those infected with Covid after vaccination have at least one ‘probably serious health issue’ in the months following recovery. Note, however, that the individuals included in the analysis had to have ‘interacted’ with their healthcare provider at least once in the previous two years to be considered for inclusion in the study, so probably doesn’t include the most healthy individuals. I suggest that it is likely that individuals with mild symptoms (the majority of infections) would have lower incidence rates of these sequelae, but this wasn’t specifically addressed in the study.

So far their data show that those vaccinated against Covid have a high risk of health issues following an infection with Covid. The question then becomes whether vaccination helps to reduce this risk. Unfortunately, while the study did include data on relative risk of sequelae for the vaccinated-infected versus unvaccinated-infected, these data appear to be highly compromised and I’d suggest shouldn’t be used. The problems are:

- The vaccinated and unvaccinated data come from different times of the year (see supplementary table 1). The data for the vaccinated group are based on infections that occurred between the start of July 2021 and mid-October 2021 (the control group data come from a matched period). The data for the unvaccinated group are based on infections that occurred between mid-January 2021 and the end of July 2021. This means that the vaccinated group were predominantly infected with Delta variant, while the unvaccinated group were were probably infected with original Wuhan variant or the Beta variant. There might also be seasonal effects that could show up in differences between the two groups.

- As unlikely as it sounds, the ‘unvaccinated’ group contain individuals that were vaccinated – the only restriction was that they were unvaccinated at the point of infection and 30 days afterwards. The paper doesn’t indicate the level of vaccination in the unvaccinated group, but given the very high levels of vaccination achieved in the USA in those aged 40 or over it is likely that the majority of individuals in the ‘unvaccinated’ group were vaccinated after their infection.

- The ‘vaccinated’ group excluded any side-effects that occurred in the weeks after vaccination (within 60 days of vaccination for the mRNA vaccines and 45 days of vaccination for the viral vector vaccines), while the ‘unvaccinated’ group included side-effects that occurred in the post-vaccination period (for those that were vaccinated after their infection).

- Indeed, analysis of the characteristics of the vaccinated participants shows that the majority were vaccinated between January and March 2021, many months before they were infected with Covid. The study data suggest that on average there was period of seven months after vaccination before data was collected on their potential side effects (six months before infection and then another 30 days to exclude acute Covid symptoms).

Thus the two groups that they compare aren’t ‘unvaccinated vs vaccinated’, but instead are:

- Had been vaccinated for some time at point of Covid infection; vaccine side-effects that occurred within around half a year after vaccination aren’t included; they were probably infected with Delta variant;

versus

- Unvaccinated at point of infection and 30 days later; probably vaccinated later; the data include short term (weeks) vaccine side-effects and medium term vaccine side-effects (months); the individuals were probably infected with the original Wuhan or Beta variant in the early part of the year.

I find this approach to the ‘unvaccinated’ group a bit strange – they had a huge pool of people to gather data from so surely there were a fair few that remained unvaccinated during the study period that they could have worked with? Regardless, the characteristics of their ‘unvaccinated’ and ‘vaccinated’ group makes any meaningful comparison impossible. Note that this means the paper certainly doesn’t offer robust evidence to support the use of vaccination to reduce the risk of Long Covid.

The study also compared the risk of sequelae after Covid in the vaccinated with the risk of sequelae after a serious influenza infection. It found significantly greater incidence of sequelae in the vaccinated-infected compared with those infected with influenza (and not vaccinated). The relative contribution of vaccine side-effects and sequelae of the viral infection in this finding remain unexplored in this study.

Thus the data seem to suggest that the sequelae might be associated with the Covid infection itself or might be linked to the vaccination – unfortunately, the paper doesn’t directly offer analysis to separate out these two factors. However, the paper’s supporting data allow us to do something interesting – compare the rate of the authors’ chosen list of health issues in individuals that were vaccinated but who didn’t get infected with Covid and the background (historical) rate of these health issues.

Or, to put it more succinctly, the data in this paper allow us to estimate the rate of vaccine side-effects alone, at least medium and longer term ones. Note that the complex method for inclusion of the vaccinated-not-infected group would mean that the data for some individuals would include health conditions that occurred within 30 days of vaccination, but this wouldn’t be the case for most individuals in the study – thus any vaccine side-effects identified would likely be biased towards the medium and longer term.

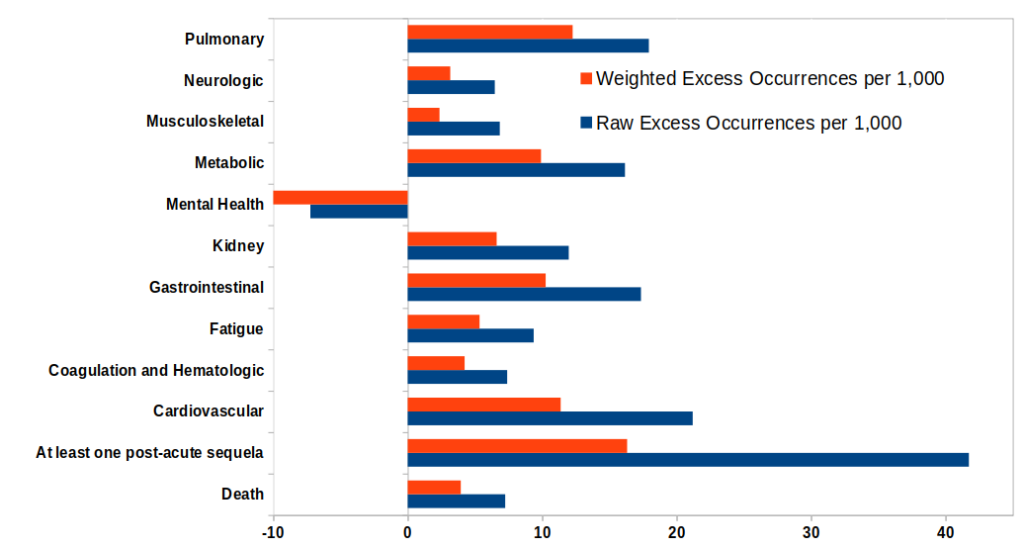

I’ve computed the excess incidence of their range of negative health outcomes after vaccination compared with the historical control data in the graph below. Note that the data in the study are complex as they applied a weighting to each study group to attempt to remove bias. In the graph below I have presented the estimate of vaccine side-effects based on the raw data in the paper, as well as attempting to apply the same weighting function as the authors used in the paper to remove bias; it is likely that the true rate will fall somewhere between these two values.

These data are astounding – they suggest that there are a significant level of serious negative health consequences of vaccination, of the order of 0.5% to 1% (and possibly higher) for each condition, and with around 1.5% to 4% of the vaccinated suffering some condition that resulted in them seeking support from their healthcare provider. This estimate is in line with the findings of the CDC V-Safe survey, which found that 0.9% of recipients of a Pfizer booster sought medical care, those reported by a whistleblower board member of a German insurance company, who said his company’s data suggested around 4% of Germans had sought medical care following vaccination, and an Israeli Government survey which found 0.3% Pfizer recipients reported hospitalisation (not just medical care) as a result of vaccine side-effects. It is a shame that the authors missed this important aspect of their data – I’d suggest that it is probably more important than their findings on ‘Long Covid’, given that the number of vaccinated individuals is much higher than the number of Covid infections, that Omicron appears to be much milder than previous variants (i.e., what were the relative risks of early vaccination versus waiting until less pathogenic variants evolved), and that individuals were deliberately given the Covid vaccines while actual infection with Covid is an act of nature.

There is a silver lining to the very dark cloud indicated in the graph above; vaccination appears to have relieved some mental health risk compared with the historical control. Perhaps we should add Covid vaccination to summer, Buddy Holly and the working folly as reasons to be cheerful?

The data in the graph above raise more questions than they answer – for a start, have there really been deaths in between 0.5% and 1% of those vaccinated, at least in the types of people included in the study? The fact that the study only looked into sequelae in people with sufficiently serious symptomatic disease to seek support from their healthcare provider might help to explain this high death rate.

These data aren’t absolutely conclusive evidence for there being significant levels of vaccine side effects, but they are highly suggestive of a problem and are certainly worth reporting and definitely would support further research to fully quantify the effect. However, for some reason there being scary levels of ‘Long Covid’ appears to be more important than there being ‘scary levels’ of vaccine-induced injury, and these data weren’t reported by the authors.

There’s one more rather odd aspect to the data in this paper that I find difficult to explain. Hidden away in two footnotes to two tables in the extended data section of the paper is the information that myocarditis in the vaccinated-infected was double that found in their control group, and in the ‘unvaccinated’ infected myocarditis was 20-fold higher again than the vaccinated-infected group. However, it is important to remember what ‘unvaccinated’ means in this paper. Perhaps it would be better to interpret this finding as:

- Myocarditis risk was double the expected (background) rate in those infected with Covid after vaccination, but ignoring any myocarditis between the point of vaccination and about six months post vaccination.

- Myocarditis risk was 40-fold the expected rate in those who were unvaccinated at the point where they caught Covid, but who were probably vaccinated after this point and where myocarditis risk includes the weeks and months after vaccination (for the majority that will have been vaccinated).

Is the greatly elevated myocarditis in the latter group a catching-Covid-before-vaccination problem or a risk of vaccination problem? We just can’t tell from their data.

What’s truly weird is that this is probably the most significant finding in their paper, yet it is relegated to a footnote; there’s no mention of myocarditis elsewhere in the paper. The authors clearly knew about it because they did include the data in the footnote, but decided to ignore it anyway. I’m sure that things would be cleared up if the authors could explain why they decided to ignore this important part of their results.

In summary:

- The authors almost certainly found that the vaccinated that suffer breakthrough infection had higher risk of negative health conditions in the months following vaccination, compared with control groups (those without prior Covid infection).

- In those not hospitalised, around 8% experienced a negative health condition of some type.

- Their data weren’t robust enough to support the conclusion that the ‘unvaccinated’ suffered increased levels of sequelae after infection, because it is likely that the majority of their ‘unvaccinated’ group were vaccinated after infection with Covid.

- The data strongly suggest a high level of negative health conditions after vaccination in those not infected with Covid, compared with historical norms. The authors decided to not analyse their data in this way.

- The authors also decided to ignore the significant results they found regarding myocarditis risk.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The authors ignored the heart issues because they would have not been able to publish their paper if they had said anything about them….

You must admit that ‘Anyone Who Had A Heart (Problem)’ might not have worked so well for Bacharach and David.

Why, it’s almost as if the people who wrote the article *want* to draw attention to certain facts by mentioning them but not following up on them. Like they might have been told to leave out anything that might imply that these vaxxes are the utter garbage that they most clearly are. Snake oil by name, snake oil by nature.

A little one for Amanuensis’ anecdotal cases bin:

A friend told me that a colleague of hers, 42, at least 2x vaxxed, had had the dreaded corona back in Jan/Feb. No problem, a few days in bed. However, 6 weeks later she was feeling so poorly and short of breath she went to A&E, where she was diagnosed with pneumonia. The A&E doctor mentioned that they were seeing that a lot – lots of people her age who had had corona, been fine, but ended up with pneumonia weeks later. Considering around 87% of the population over 18 is at least 2x vaxx, the odds are that those showing up in A&E with pneumonia long after the illness has passed are vaxxed.

A cynic would say that the only things the vaxxes appear to do, other than generate profit, is ruin immune systems. Which generates even more profits.

A senior nurse told me I’d made the right decision not getting vaccinated (this was at the height of the omicron / booster madness)

Made me wonder just what she had seen and heard about the side effects.

A senior pharma exec paying $200,000 to avoid being jabbed, really should tell us all we need to know about its safety.

What I don’t understand, is why these sorts of studies keep getting funded and published. They never show anything good, and the lines between ‘vaccinated’ and ‘unvaccinated’ are inevitably blurred.

of course, should they wish to actually compare vaccinated with unvaccinated, they could actually do this, but it is doubtful we will ever see this sort of study.

Maybe in the efforts to create these papers the actual useful data is gathered and calculated and obviously not published, but what is published tells us a few things about the authors, 1) they can create credible looking papers whilst disguising things, 2) they know what is actually going on and could expose the truth if they don’t get their future funding?

seems strange that some glaringly obvious omissions are made when they should have the data to make them.

“they know what is actually going on and could expose the truth if they don’t get their future funding” So reminiscent of the climate scam

First we had the bad back, then we had stress. Now we have Long Covid as the go to condition to get that sickie note signed

There’s also the oddity that 95% of the subjects had no positive test in the whole of 2020 and 2021.

That doesn’t seem at all credible.

https://twitter.com/jengleruk/status/1530819194387841027?s=21&t=Qw4fwDwthz8KfuGZqokk_g

That was part of the inclusion criteria for the control group. There might have been more cases but they weren’t considered for the study.

Hmmm are you sure?

“We first identified users of the VHA who were alive on 1 January 2021 (n = 5,430,912).”

“Among these, 163,024 participants had a record of a first positive SARS-CoV-2 test from 1 January 2021 to 31 October 2021, and 5,140,387 had no record of any positive SARS-CoV-2 test between 1 January 2020 and 1 December 2021.”

So out of 5.4m users alive, 5.1m had no record of any positive test.

(There will have been deaths during 2021 but not material to my point.)

That was the point I was making – seems much too low surely?

Thank you – btw – for a superb analysis of this “study”.

The journalist Naomi Wolf has been writing up the findings of thousands of Docotors and scientists that have come together to comb over the data that Pfizer and the FDA/CDC wanted to hide but were forced by court order to release.

It will come as no surprise that they wanted to hide the data for good reason, the data shows that pharma knew the vaccines offered negligible benefit and that they are lethal to significant numbers of humans, the evidence that the vaccines are often lethal to the unborn is particularly horrific.

Delbigtree interviews Naomi Wolf –

https://thehighwire.com/videos/pfizer-docs-fda-hid-pregnancy-baby-harms/

Plandemic.

Bourla was invited to Bilderberg

It has always seemed very clear to me that long term vaccine injuries would be passed off as COVID injuries wherever possible.

This study seems to be one of many examples.

Thats what convid was all along – killing people via various methods – lockdowns, ventilators, remdesevir, midazolam, expelling sick people from hospital (ie removing their treatment) etc and then calling it convid. Then the transparently fraudulent method of counting convid deaths comes into play – any death within 28 or sixty days of a positive bent PCR test or presumed convid or whatever the hell they like – theyre just making it up as they go along. But convid is definitely real – ask government scientist ammenuins, hell tell you.

Theyve been caught red handed but they dont care and due to the fact we have criminals running our media, government, NHS, MHRA etc they can just keep going with their two plus two equals five bullcrap gravy train. Long covid is more pseudo science bull, just like the nonexistent sars cov 2 virus, based on PCR testing fraud and pseudo science. The monkeyscam also relies on PCR testing – so they can relabel things like shingles – caused by the jabs – as monkeyscam – then use this tired old trick to terrorise everyone with. Yet its still being unquestioningly hawked by people who should know better by now.

Yesterday DS posted a petition to be signed which sounded interesting. The thing is, and noone commented on this, the criminals in HMG have already put the tip of their thumb up to their noses, made a waving gesture with their fingers smiling like Matt Hancock injecting a six year old child with experimental genetic poison, with a clear message that there will be NO investigation into vaxx injuries and deaths because the MHRA is already doing a great job:

Parliament will consider this for a debate

Parliament considers all petitions that get more than 100,000 signatures for a debate

Waiting for 2 days for a debate date

Government responded

This response was given on 5 January 2022

Read the response in full

The Government has commissioned a public inquiry into the COVID-19 pandemic and has no plans for a separate inquiry on vaccine safety. The safety of COVID-19 vaccines is monitored by the Medicines Healthcare and Regulatory products Agency (MHRA).

The MHRA has authorised COVID-19 vaccine supply following a rigorous review of their safety, quality and efficacy. The clinical trials of the vaccines have shown them to be effective and acceptably safe; however, as part of its statutory functions, the MHRA continually monitors the use of the vaccines to ensure their benefits continue to outweigh any risks. This is a requirement for all authorised medicines and vaccines in the UK. This monitoring strategy is continuous, proactive and based on a wide range of information sources, with a dedicated team of scientists reviewing information daily to look for safety issues or unexpected events.

The MHRA operates the Yellow Card scheme to collect and monitor information on suspected safety concerns or incidents involving vaccines, medicines, medical devices, and e-cigarettes. The scheme relies on voluntary reporting of suspected adverse incidents by healthcare professionals and members of the public. The scheme is designed to provide an early warning that the safety of a product may require further investigation.

Up to and including 15 December 2021, the MHRA received and analysed: 145,446 Adverse Event reports (ADRs) from people who have received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine; 240,065 UK reports of suspected ADRs to the AstraZeneca vaccine; 24,721 UK reports of suspected ADRs to the Moderna vaccine. For context, up to same date, approximately 46.4 million Pfizer/BioNTech Vaccines, 50 million AstraZeneca vaccines and 2.8 million Moderna doses had been administered as first and second doses.

The overwhelming majority of these reports relate to injection-site reactions (sore arm for example) and generalised symptoms such as ‘flu-like’ illness, headache, chills, fatigue (tiredness), nausea (feeling sick), fever, dizziness, weakness, aching muscles, and rapid heartbeat. Generally, these happen shortly after the vaccination and are not associated with more serious or lasting illness. These types of reactions reflect the normal immune response triggered by the body to the vaccines. They are typically seen with most types of vaccine and tend to resolve within a day or two.

The continuous review of available evidence from UK Yellow Card reports of suspected side-effects to the vaccines and other healthcare data does not suggest that the COVID-19 vaccines increase the risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attacks. The benefits of the vaccines in preventing COVID-19 and serious complications associated with COVID-19 continue to far outweigh the risks in the majority of patients…….

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/602171

Lying genocidal filth. These brstrds need stringing up. Even if you believe their lies about convid, it s openly admitted to have such a low mortality rate as to be a nonexitent threat. The OG super killer mega strain has a survival rate of 99.9percent from natural immunity. Theyre taking the piss out of everyone with this but because we only have lying criminal scum in positions of power and influence, this utter nonsense keeps on going. Ammenuis and his ilk are more than playing their role in perpetuating this scam, with articles such as the one above.

Unfortunately I am coming to the conclusion we are approaching the end game and there will be a lot of dying. Maybe we’ll be back to the stone age at the end as I feel it has a high chance of ending in a full nuclear exchange or mass bio cull.

The world has been through these power transitions many times before but never with enormous global destructive power available. My pessimistic belief is we need a truly external threat to get us out of this. Volcanic, meteor or even alien! Either way pretty dark.

I remember a poll done in the UK in 2021.

On average, people thought that about 7% of the population had died of covid.

That would have been around 4.6 million people.

Acquaintances of mine (mainly work colleagues), on average, thought it was over 15% dead of COVID.

Well paid and well ‘educated’ folks, too.

Give it more time for the vax effect to work its magic…

I hope not! I was seriously contemplating what to do when almost everyone who got the jab, started getting ill and dying. The thing which really brought it home, was knowing (at the time) that almost no kids had had the jab. So basically millions of orphans … and the only logical “solution” was to force everyone to take some kids.

And, then we have the professions which had gone over the top bonkers like teachers …. so no retirement for anyone with any qualification … back to work teaching the brats of those stupid enough to take the jab.

And no peace for anyone else, because with an infrastructure designed for 68million, and only ~10million left … there would be no peace for the wicked.

On the other hand, we’d all get an opportunity to use diggers. And parliament would either have died … or if they remained, they’d have been put on trial for mass murder.

It could work out!

A lot of “educated” people just have good memories and zero logical or critical thought capability.

Average age of death before covid: 83, average age of death with covid: 83

Last time I checked it had killed around 9000 people in England, 0-65 without comorbidities. NHS figures.

Wasn’t “of” covid around 21,000?

What’s that 0.035%?

You only had to look around you to realise it was massively hyped. No one was dropping dead in my street.

Long Covid Study Shows High Rates of Serious Vaccine Side-Effects

or

Long study shows High Rates of mRNA gene transfer technology Side-Effects.

Meanwhile, the UK’s International Health Service has quietly slipped mRNA gene therapy injections onto the childhood vaccination schedule.

Because they hate us and they want us dead.

I heard someone comment that the lies and cover up will not end because if they lost control they would be hung from lamp posts in the street!

Yes that does make me wonder how the Court of Public Opinion by Riner Fuellmich will work out.

The only way we can deal with the mRNA Gene Transfer Technology, which was intentionally misidentified as a vaccine for covid19 is to comprehensively denounce the existence of the covid19 virus. Anyone who says that a PCR test proved covid19 existed must be shown that the test was nothing more than a deception, designed to fool the public into accepting the experimental mRNA jabs. The lock downs, social distancing, mask wearing etc, etc were for dramatic effect only.

“There are no useful data”.

The story of this shambles. Now I recall that in the 19th century, one of the major things the army did to help soldiers was ti commission extremely detailed maps (one to 8,000?) providing all manner of geographical data. Yet time and again, all manner of data, and not least potentially incriminating data has been kept from us, or made very difficult to access. I can only conclude that, in contrast to the army with their Ordnance Survey, they are trying to hinder us. And apparently hinder us from perceiving possible crimes against humanity, and liability for huge damages.