It is said that people can only worry about one thing at a time; if so, then I’m sure that few people are currently worrying about the recent increase in Covid cases in the U.K. This is a good thing – the hospitalisation and mortality rates of Omicron appear to be significantly lower than those of previous variants, so it’s surely time to just accept Covid as another type of cold that’ll give us all an annoying sniffle every couple of years.

But the sticky problem of the vaccines remains. Do they work or have they made things worse? Luckily, the UKHSA (just about) continues to publish the Vaccine Surveillance Report and as a result we can explore how the vaccines are impacting on Covid in England.

Cases

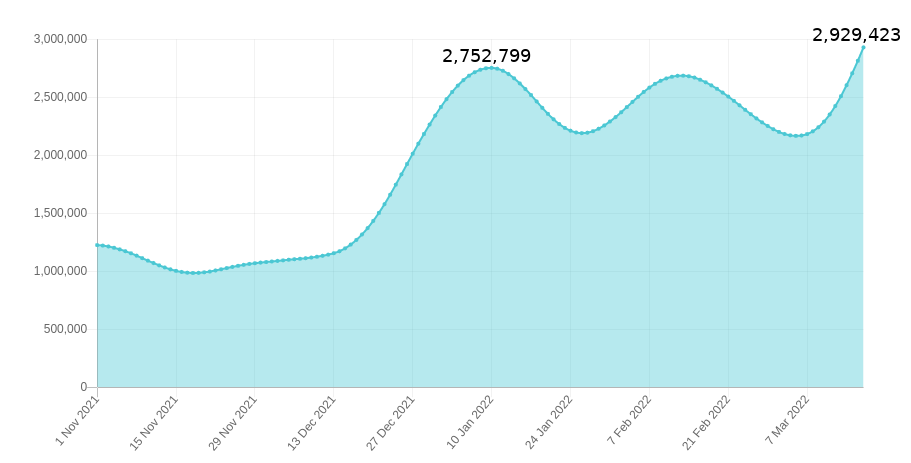

The new Covid wave, as defined by data from the Government Covid dashboard, appears to be gathering steam with new cases hitting 100,000 per day; it is easy to forget that the terrible Covid wave during January 2021 peaked at around 60,000 new cases per day (though this was admittedly before mass lateral flow testing had been brought in). We’re told that recent variants are nearly as infectious as measles – ignoring the surprisingly low household infection rate of Omicron variant, which doesn’t support the measles comparison. What do the data say?

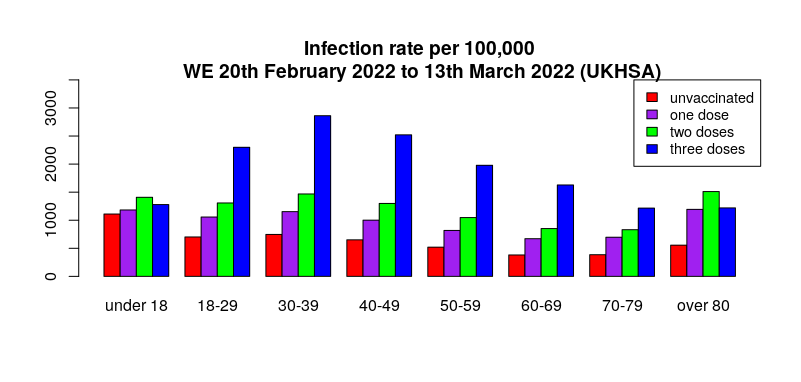

Yet again, the real-world data suggest that infection rates are generally highest in the triple vaccinated, with the lowest infection rates in the unvaccinated (see here for details on methodology and limitations). Could it be that the evidence for Omicron variant being as infectious as measles is only found in countries with high vaccination rates?

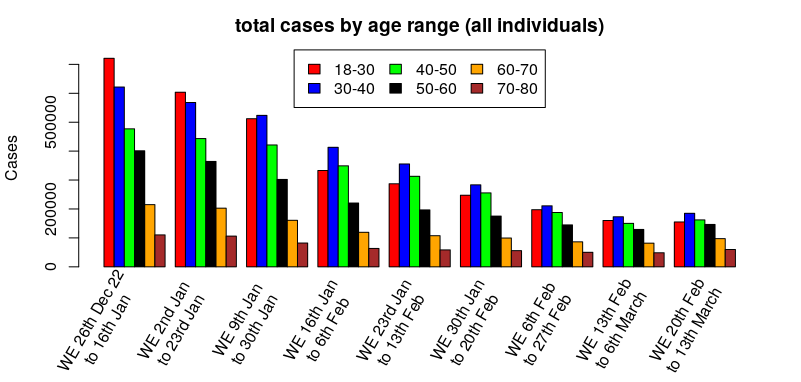

The delayed nature of the UKHSA data meant that in last week’s report there was no sign of the then emerging Covid wave – the question is, can we now see the latest Covid wave in the UKHSA data? Looking at all the weekly totals for all Covid cases there’s a hint of an uplift for most age groups in this week’s report.

Hmm. The cases have definitely dropped significantly since the beginning of the year, but it’s a bit difficult to see if it is turning around – how about looking at the percentage change by week, that is, relatively how many more/fewer cases there are compared to the previous week:

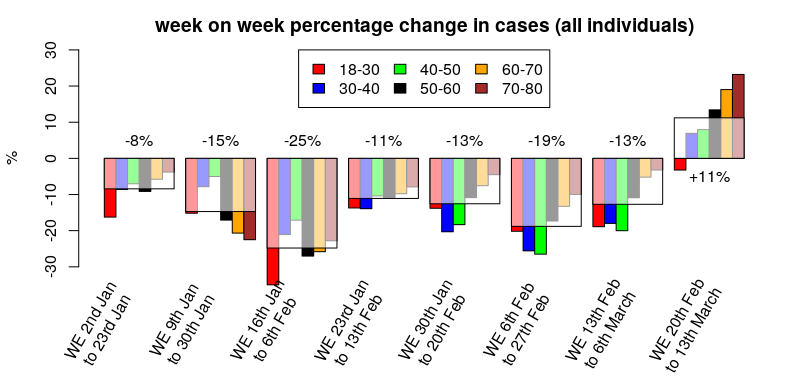

That’s better – cases appear to have been dropping since the start of the year, but this week’s report suggests that the reduction in overall cases has stopped and perhaps the start of the new wave can be seen at the far right.

What about by vaccination status?

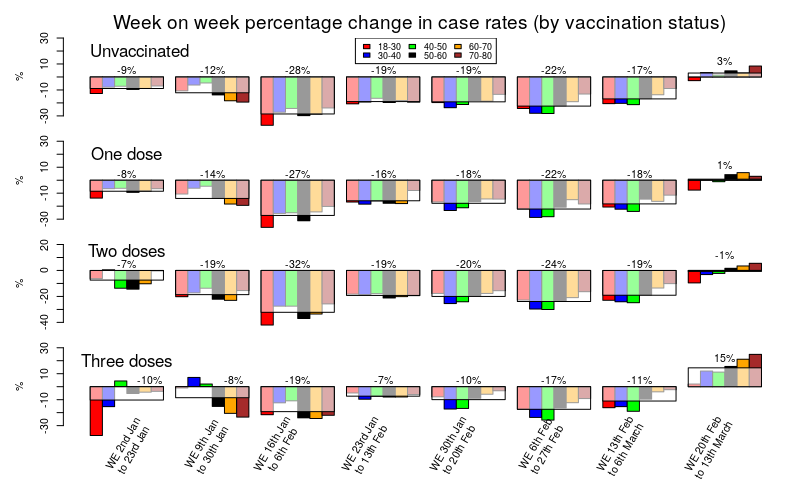

Hmm. That’s a busy graph, but perhaps if you stare at it for long enough a general pattern should become visible.

The change in cases for the unvaccinated, those with only a single vaccine dose and those with a double vaccine dose are very similar; a sustained reduction in cases since the start of the year, but with cases remaining broadly flat in this week’s data compared with last week’s.

Three doses of vaccine show a very different picture. Compared with the unvaccinated or those with one or two doses, the data for three doses show a much slower rate of reduction in cases, with generally about half the rate of reduction in cases compared with those that had taken fewer doses. Also note that this isn’t simply because the triple vaccinated had fewer cases; a glance at the cases graph earlier in this post clearly shows that case rates in the triple vaccinated are still higher than the unvaccinated, and previous posts have shown similar data for earlier time periods.

The big difference in the triple vaccinated, however, is in that final time period on the graph above (the column on the far right); in the latest data we can see that case rates have recently been broadly flat in the unvaccinated, the single dosed and the double dosed – but in the triple vaccinated we see a significant (15%) increase in case rate. It is noteworthy that the triple vaccinated make up the majority of the population for most age groups; are our new Covid waves being driven by the triple vaccinated?

These are still early days in the progression of the current Covid wave and this analysis should be regarded as preliminary – next week’s data should be interesting, if they provide it…

One more note on cases. I mentioned last week that the Zoe symptom tracker was disagreeing with the UKHSA and U.K. Government data on the drop in cases that we’ve seen over the last two months. The Zoe Symptom tracker has seen a sustained level of cases during that time (I have hypothesised that this is due to the 90 day exclusion period in the UKHSA data that would remove any reinfections). I mention Zoe because Thursday marked the point where the Zoe app’s estimate of the number of individuals currently infected with Covid in the U.K. exceeded the case rate during January, and with no sign yet of the increase in cases starting to reach a peak.

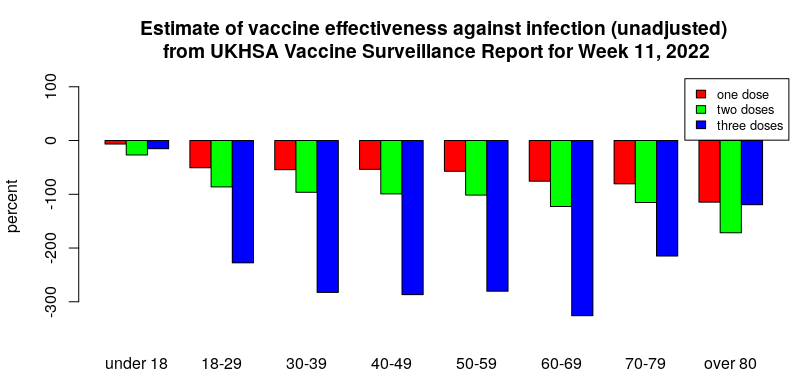

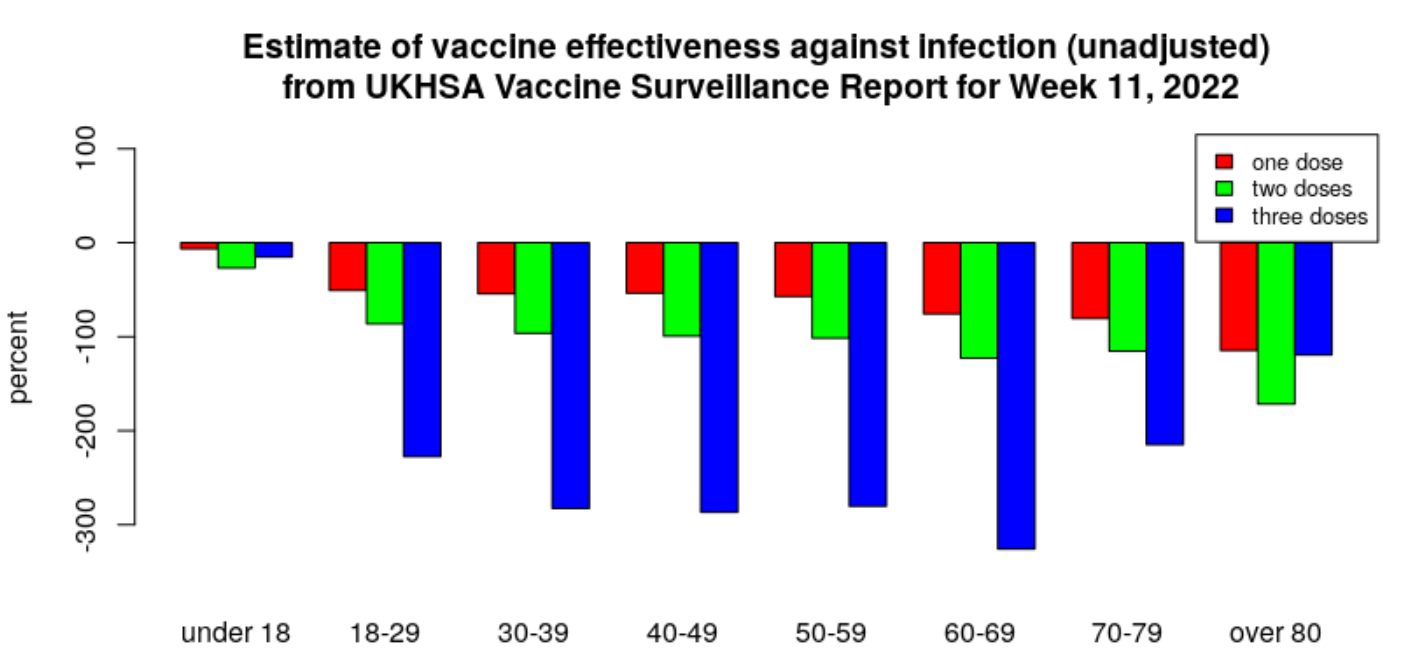

For the historical record, this is the current estimate of vaccine effectiveness according to the UKHSA data.

All are negative, meaning the infection rate in the vaccinated is higher than in the unvaccinated. It has reached as low as minus 300% for the triple-jabbed aged 30-70, with those in their 60s faring worst of all, meaning these groups are more than four times as likely to test positive as their unvaccinated counterparts.

Hospitalisations

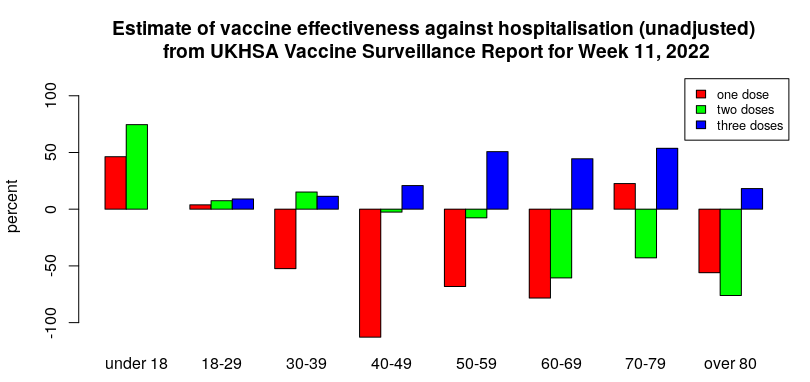

The Covid vaccines appear still to be offering some protection against hospitalisation after Covid infection for those that were recently boosted, but the hospitalisation rate in those that stuck with one or two doses of vaccine is now much higher than that of the unvaccinated.

I’d note that it is possible that the higher risk of hospitalisation in those having taken only one or two doses of vaccine reflects them being more vulnerable than average (and thus passed over for the booster dose). If so, this ‘healthy vaccinee’ effect implies that the vaccine effectiveness against hospitalisation and death will be overestimated. That said, there remains the possibility that waning vaccine protection starts to be associated with increased risk of serious disease (possibly via antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) mechanisms, which often only appear when the initial immune response starts to wane). It would be useful if some research was undertaken in this area.

An important aspect of the above graph is which age groups get the benefit of reduced hospitalisation after vaccination. The age group from 50 to 80 appears to have a reasonable level of protection (about 50%) and this might well support vaccination in that age range for those that are happy to keep on taking booster doses indefinitely (dependent on side-effect/complication rates). Protection in those aged over 80 appears to be poor – this is unfortunate as it is that age group that gets the largest share of hospitalisations and deaths. I also note that there appears to be very little reduction in hospitalisation in those aged under 50; it is questionable whether this level of reduction is at all relevant for younger individuals.

Deaths

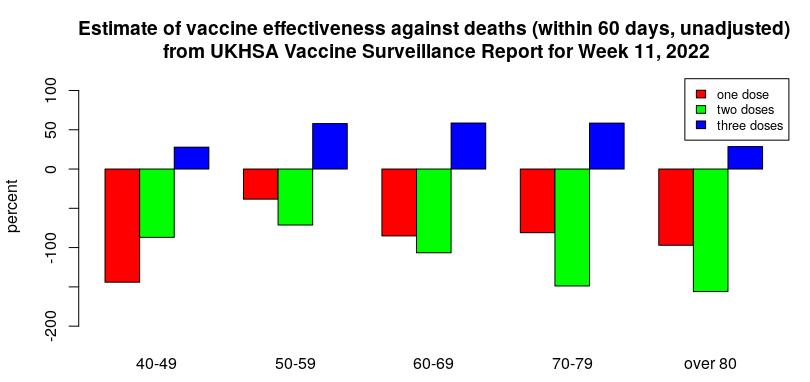

The UKHSA statistics for deaths within 60 days of a positive test show a similar trend for the effectiveness of the vaccines to that seen for hospitalisations (only data for those aged over 40 are shown – Covid death rates are too low in those aged under 40 for meaningful analysis).

It is important to note that deaths with Covid have reduced significantly since the Omicron variant arrived. Thus, despite the apparent protection against Covid death offered by three doses of vaccine, it is questionable whether there is now much in the way of absolute, real-world benefit.

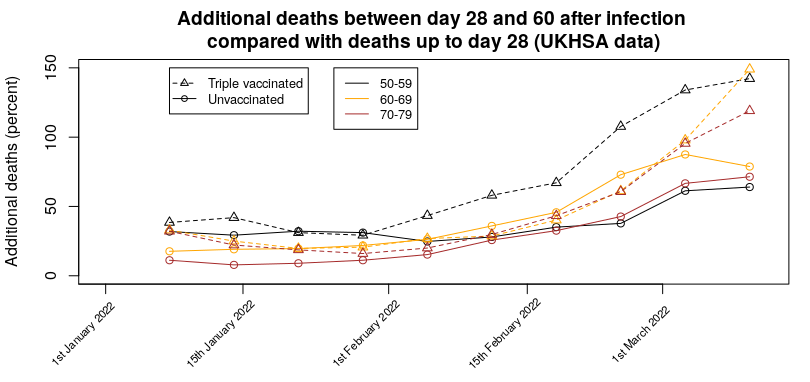

There is a worrying trend in the deaths data, however – the change in distribution between deaths within 28 days and within 60 days.

Historically, most deaths with Covid have occurred within 28 days of infection. However, there have been some additional deaths beyond this point; in general, each week’s report has seen an additional 20-25% deaths with Covid between 28 and 60 days after infection.

Over the past few weeks, the proportion of deaths with Covid in the 28 to 60 day period after infection has steadily risen until it accounts for approximately as many deaths again, as seen in the graph below.

Even worse, there appears to be a vaccine effect, whereby there are more additional deaths in the triple vaccinated group (approximately 140% of the 0-28 day deaths in the latest report i.e., nearly one and a half times as many deaths occurred in the 28-60 day period as in the 0-28 day period) compared with the unvaccinated (approximately 70% of the 0-28 day deaths i.e, the number of deaths occurring in the 28-60 day period was around two thirds of the number occurring in the 0-28 day period). This means that in the triple-vaccinated we’re seeing more deaths with Covid in the 28-60 day period than in the 0-28 day period. This effect is also visible in the data for one or two vaccine doses. For the most recent week the day 28-60 deaths are 130% (single dosed) and 170% (double dosed) of the 0-28 day deaths.

It isn’t clear whether this effect is due to infection with the Omicron variant taking longer to get to the stage where hospitalisation is required, people remaining seriously ill inside hospital for longer, or more people dying outside hospital. It is also possible that this effect is due to changes in treatments being used in hospitals.

Given this effect, it is likely that the current ‘official’ death figures for Covid are now lower than they should be (though I note that ONS excess death estimates have also been low since Omicron arrived), and that official estimates of vaccine effectiveness against death will overestimate the protection offered.

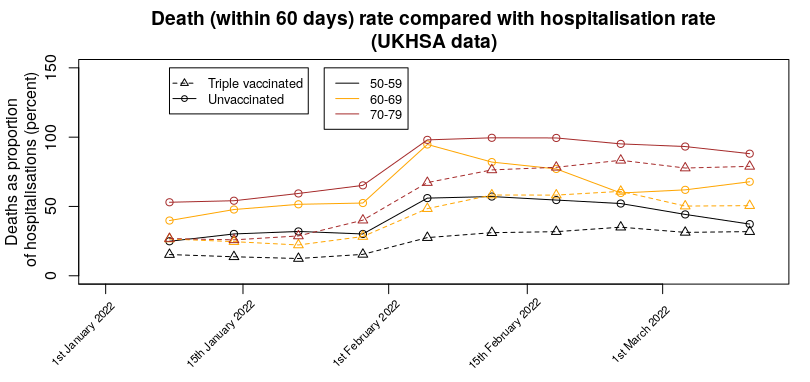

Another interesting effect seen in the deaths data is the ratio between the deaths rate and the hospitalisation rate.

There does seem to have been a change in the number of deaths compared with hospitalisations over recent weeks, with a marked increase in February, so that more are dying per hospitalisation. It is unclear why this has happened. Note that is isn’t simply the hospitalisation death rate – many deaths with Covid appear to be occurring outside a hospital setting. This effect is seen most clearly in the proportion of deaths vs hospitalisations for one and two doses; for those aged 70 to 80 there are more deaths than hospitalisations (about twice as many for a single vaccine dose, about 50% more for the double vaccinated).

One more thing…

Arguably, the most important news in this week’s UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report was buried in the text (my bold):

From April 1st 2022, the U.K. Government will no longer provide free universal COVID-19 testing for the general public in England, as set out in the plan for living with COVID-19. Such changes in testing policies affect the ability to robustly monitor COVID-19 cases by vaccination status, therefore, from early April onwards this section of the report will not be updated. Updates to vaccine effectiveness data will continue to be published elsewhere in this report.

This was probably inevitable – the real-world data on the vaccines are consistently failing to support the Government’s position that the vaccines have actually helped significantly. While the excuse given appears reasonable at first glance, a few minutes thought reveals it to be weak – while there might be issues with overall cases and testing, testing at hospitalisation and to a certain extent death will continue. In addition, it is likely that routine testing of healthcare workers will continue for some time. It would have been trivial for the UKHSA to have continued to show data for hospitalisations and deaths and included a section on case rates in healthcare workers. But instead they’re using the occasion as an excuse to remove all data. I also note that the Zoe symptom tracker app has lost funding – their data were also going against the official narrative. Thus, like tractor production in the Soviet Union of old, the only statistics we’ll be allowed to see are those that aren’t inconvenient to the state.

Hopefully we’ll get at least one more set of data to see how the impact of the more recent changes outlined in this post have played out.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

*Not* Cassandras! As many of us pointed out yesterday btl, she predicted the truth but was doomed to not be believed. Sage etc are exactly the opposite. ( It’s us Sceptics that have been the Cassandras ).

NB. You need to edit; “poured” ( para 6 ) should be “pored”, and you’ve written “their” instead of “they’re ” higher up ( 1st para ).

That would be a quantum leap of progress.

So true! I remember posting on FB a while back asking if there were any other Cassandras out there, meaning – like US, not the SAGE scientists! Cassandra made ACCURATE prophecies (that weren’t believed).

Cassandra was cursed by Apollo for having spurned his advances. We can all relate, I’m sure, to the terrible burden of knowing what’s coming and not being able to get anyone to believe it. One of her first prophecies was of the Trojan horse. A gift which is received with gratitude but contains something deadly.

There’s a great comic strip in which Cassandra exacts a kind of revenge on Apollo. Sadly I can’t find the original.

I remember when Toby insulted us all for questioning the vaccine. In the end he changed the name of the site, Cassandras indeed.

You can just feel that they are going to impose restrictions again can’t you. It might be my usual negativity but there is no way they are going to let things continue like this and a lockdown will come once again.

The only thing we have in our favour is the fact that this will perhaps wake a few more people up .. Maybe…

I personally have the same sense of doom as in April 2020 when it became quite clear that the coronavirus circulating was not anywhere near as dangerous as governments and media were saying and still we continued on the same trajectory. The lack of course correction in the face of clear evidence made me realise something else was at play.

This winter feels the same. This thing being called Omicron is a joke as far as a threat to health goes and there is complete disconnect between the medical threat and the measures being imposed and the fear being promoted.

It just doesn’t make sense. What is behind it is mere speculation, but what we can say without any hesitation is that this just doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. And if I know it, those running the show know it.

I am absolutely certain based on reports from funeral homes in different parts of the country that the excess deaths we had in January and February of this year, were due to vaccinations of the most elderly.

A number of funeral homes reported their busiest ever months during that period, and it just coincided with mass vaccinations of the most elderly people.

The purpose of a lockdown now appears to be motivated by the order they have received to implement the vaccine passport, which will later become the CCP social credit system. You cannot introduce something like that unless you create a crisis. The issue they have is that just dont have the data to justify it, but that hasnt stopped them so far.

Not saying you are wrong but

I was out and about 7 days a week as a ‘key worker’ for 12 months from March 2020. There was no increase in activity by funeral parlours evident on the empty road. It would have been very obvious with the empty roads. Funerals were not banned, just the number of mourners greatly curtailed.

They never used the designated Super Morgu (an out of town coverd Go Cart track), nor the Covid Recuperation Hotel and the didn’t start the local Nightingale until late summer by which time the commandeered Nuffield still remained idle.

But they did other things to create a climate of fear, not least having empty ambulances cruising around with their sirens blazing for no good reason (empty roads).

Omicron was a bit of a damp squib – but just wait until you see the next one that will be 77% more contagious than Omicron!!!

It all makes perfect sense to those cashing in from all this. Although you’d think they themselves are subject to travel restrictions, and face mask wearing, and having to see the whole country in abject zombie misery.

You are localising the issue. The conspiracy is global and rest assured those directing operations are neither interested nor affected by the emiseration of national states.

Surely that is a mistake, it could be 66% more contagious or even 666% more contagious it all depends on Neil latest model.

Also as the next variant should be pi, it will be 3.1416….. times more deadly as well.

6pm yesterday. Accidentally caught 30 second intro of ITV 7pm news.

News guy kneeling off studio desk in mansplaining power pose

“New Variant Omnicon surges past (100k?) ! Wales and Scotland impious Xmas sanctions !

England holds firm !

Join us as 7 for the full story”.

What a load of obvious bollocks.

The panzers are coming. Bozo is ready to mobilise Dad’s Army.

“Stand by your beds.”

Bombs Away Monday December 27th.

I haven’t watched TV in over ten years. Doesn’t sound like I’m missing much.

Raise you by five years to 15 (same as BT landline).

As I said, caught by accident so the brazeness shocked.

People fall for this shite?

I remained confident for all of Lockdown Proper and most of Lockdown Lite that the worst was nearly over and that we were on a steady path, albeit slowly, towards Freedom.

Only as they introduced Tiers with the media constantly hyping up the supposed dangers of Covid did I realise there was no end in sight, just like now.

The only puzzle was why?

Only then did I begin to look at what, until then, had been conspiracy theorists and here we are again, over 12 months later.

I believe if Johnson goes for a shutdown anything like SAGE want it would set in motion the chain that would lead to his removal from power later in the year. He will do something to appease SAGE but it won’t be anything like a harsh shutdown. It will either be Sports stadiums or some hit in hospitality, where Rishy Washy again fire up the printers.

Perhaps people will get so angry they’ll write yet another e-mail to their local MP in the hope of getting another copy + paste standard reply.

I’ve noticed a marked change in the response from my MP. (All my communications with her have been courteous and considered.) Last year, she did indeed reply with obvious copy and paste jobs from the Whips’ Office but, this year, she’s simply not responding at all. It’s almost as though she recognises that the wheels are falling off and doesn’t want anything more on the record to embarrass her in the future.

The prewritten responses I get (from the whip’s office) talks of all measures going against my [planted] MP’s ‘natural libertarian’ beliefs and that they’re only temporary. Lots of bullshit about unprecedented times and killer diseases bla bla bla.

He then goes on to vote in favour of everything the government wants.

I always remember the real response I got from him after I was particularly scathing of him and his party. Completely different writing style and a complete lack of professionalism.

It might have been funny had the subject of my email not been so serious; the suicide of a close family friend, undoubtedly due to lockdown/scaremongering.

I found an unsolicited message from my MP in my inbox!

It must have been because I thanked him for voting against VPs but he sent me Xmas greetings and thanked me for my comments.

I must be getting through, even as only a gauge as to what the Lunatic Tendency are thinking (and I’m always civil – I won’t give him an excuse to delete me)

They will mostly be happy to have been permitted a better Xmas than last year.

Canada has just gone into ‘one household at Christmas’ lockdown – exactly the same as last year when they locked down on Christmas Eve. One newspaper headline: ‘The best gift you can give this Christmas? Not infecting others with covid’. It’s so strange how much in parallel this year is with last year and with so many other countries in lockstep and yet nobody seems to remember. It’s as if the financial reset was supposed to happen then and has been put off till now. I’d guess there’ll be an announcement today that we’re reduced to one household from tomorrow – but we could just ignore it.

We can and must ignore it. I will be.

People really do seem have the memories of goldfish.

This past summer Israel pushed the booster shot on the basis that although the vaxx provided super-duper fantastic protection, Delta was a game-changer and necessitated a 3rd shot. Until November here in NL the OMT was still saying 2 shots would do. When this turned out to be nonsense (huge influx in hospital, half were vaxxed) they said a 3rd shot was necessary because of – Delta. Now, without batting an eyelid, the 3rd shot is necessary because of – Omicron.

Of course they will impose new regulations asap.Ruining Xmas was almost a step too far last year.

Now they will probably wait until the extra Bank Holidays, with many people good and sloshed, before cancelling New Years Eve since that primarily only affects younger people.

It would take a very brave Hotelier to have put on an expensive NYE base this year such was the risk of cancellation.

Of course they are going to impose restrictions. How else could they claim later that they “fought” and won against Omicron? In Germany the restrictions were already announced to come in force from 28 December – with no data to support them whatsoever. It’s not like they need any data. All they need is public support.

Yesterday John Campbell showed how Australia has decided to ignore the doom mongers and allow permissive spreading of Omicron in order to achieve herd immunity. Well worth watching.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVl5OkHcvf4

Sanity has now broken out in Australia, Japan, and South Africa. The results will most likely be dramatic and impossible to cover up. All very encouraging.

It wouldn’t be the first time a government leader makes encouraging noises about living with the virus only to go back and impose measures that look a lot like the pursuit of zero-covid.

Very true. Dutch approach March 2020 – December 2020 was stop hospitals from being overwhelmed, find better treatment, be better prepared. Shops were never shut, schools for about 2 months, primarily because parents refused to send their children, it was not the original decision of the government. No stupid face rags. Life was pretty normal, people who visited all commented on that. I remember the head of the OMT at some point saying it was never the intention to stop people from getting a cold, they just needed to keep people out of hospital.

Since December 2020 the face rages were imposed, there was a night curfew for a few months, shops shut for 5 months, etc. – all on the direction of Berlin/Brussels. I believe it is Germany that decided Europe should pursue zero covid. Let’s face it, not the first time Germany believes that as long as it persists it can overcome anything, no matter how impossible – this would appear to be a fatal flaw in the German character.

Yes Japan and sth Africa but NO Australia – That doctor knows nothing about Australian politics – it’s a federation – scott morrison is another fool who talks jibberish and knows he cannot control state law – there is nothing sane about Australian politics right now – most states have passed pernicious covid laws (especially Victoria) – citizens like me are prevented from entering the country to see my close family etc. without being stuck in a prison for two weeks on arrival and further heavily discriminated about what i can do and where i can go. It is as bad a Canada – some states put you in a detention facility for refusing a test (let alone testing positive)… it is out of control and we cannot stop fighting for our fellow humans. Please don’t misinform people more.

A taste of Covid regulations in Australia:

https://www.reddit.com/r/LockdownSkepticismAU/comments/rmmu3o/fuck_this_cunt_mandatory_masks_and_density_limits/

I rarely still watch John Campell. I found his earlier stuff, like vitD deficiency/covid.

However, he seems unable to deal with the ‘vaccines’ without his bias for them leaking through. Same with masks. And Ivermectin.

One example was the obviously elevated status of his eyebrows, when talking about the remarkable coincidence in reduction case numbers after Ivermectin take up. While being astounded at this very interesting coincidence, he then goes on to say that other things could also be contributors/responsible – the high level of mask wearing, for instance. But, looking at the graph displayed alongside him, as he says this, you think, “okaaay, but of course, they were wearing those masks prior to the Ivermectin uptake …. when the cases were sky-rocketing.

After some positive comments about Campbell recently I went back to have a look – after about two minutes – “our amazing vaccines.”

FFS I thought, must be watching the wrong John Campbell.

Man’s an idiot.

No, he’s not. He may be wrong about some things but he provides very useful information about others.

Bearing in mind, he’s a Nurse, not a ‘Doctor’ in the accepted sense so his analysis must be approached with a good deal of caution.

He accepts, almost unquestioningly, that official data sources are reliable.

Oops, forgot to complete that with the words: to be quite good.

Groan I really must finish my sentences: take up in Japan.

I really must finish my sentences: take up in Japan.

Will this become highly contagious though? We can only wait and pray that is does – obliterating people’s aquired imunity to it in the process.

I can’t see Dan Andrews rowing back on anything. For plenty of Aussies I would imagine he will remain a marked mine for the rest of his life.

‘Sage will look very silly indeed’. Sage have looked very silly indeed from the outset. But don’t worry they will all be Knighted for their services to the ‘Great Reset’. Pat will be double knighted and they will all bugger off with their big fat Pharma cheque.

I think the problem here is that the government will also look “silly” if they don’t have more restrictions now, because it will show that restrictions imposed so far have not been needed. They could use the cover of the jabs, but they could have used them before and they didn’t. Why not?

I really think this presents an opportunity for the government to say it wasn’t us, it was the science/ media who forced pointless lockdowns upon you. This presents an opportunity to highlight that locking down earlier and harder would have made little difference in March 2020, the disease was already endemic before we even knew it was here. It is a load of bollocks of course, but the government would far rather, at a public enquiry, fight a challenge that they did too much rather than they did too little!!!

They’ve had many previous chances and not taken them, though of course it’s possible that pressure from backbench MPs may be forcing their hand now.

However the fact that Omicron seems to ignore vaccines is a double edged sword. In the rational universe, it would be a reason to stop vaxxing people and get back to normal, in the covid universe it’s a reason to keep on vaxxing people.

My thoughts exactly. If you wanted to create a world in which people are vaccinated regularly and were expected to have to justify their “immunity status” with a health passport, you would want:

(a) Vaccines that don’t really work for very long – check

(b) New varieties of virus that “evade” the vaccines – check

Add a complicit media that stirs the public into a frenzy of fear when each variant appears and bureaucracy/government that plays along and you’re all set.

Exactly!

The trouble is Bozo has already stated how brilliant lockdowns have been. The public enquiry will be a white wash and tell us how brilliant lockdowns have been. They want more lockdowns in future for climate change and what ever the next big scarient is. Lockdowns have to be proven to be successful for the public to buy future lockdowns. Hence introducing restrictions when the infection rate is already falling.

Good point. In particular as the ‘scientists’ are trying to deflect the blame for overselling the gunk’s efficiency onto the politicians. Surely the politicians are not amused about that and now eager for a payback opportunity.

Moronic is essentially a common cold variant. ‘Everybody’ gets it. No one dies ‘from’ it. It doesn’t match the 3 genetic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 in contrast to all variants so far. The symptoms are runny nose, sneezing, headache, cough , etc.

To Toby’s point that is more about incompetence than anything deliberate.

What we can’t forget is that we haven’t had a functioning government in the UK for the last 40 years of the EU.

It’s been very clear since the referendum that they haven’t a clue what they’re doing.

Make no mistake, Johnson is a fully paid-up member of team NWO. So if the regime think they can get away with it (and by using that term I mean the entire cross-party political class who are committed to the ongoing coup) they will implement more controls and restrictions regardless of hard evidence or data – because that is what they have always done with the covid hoax, and what they have been doing for decades with the climate scam.

It used to be the case that when people got a cold in winter, they took some lemsip and carried on. If that cold developed into a chest infection, they stayed off work, rested and took medication. If it developed further into flu they would seek antibiotics and if in very rare cases it progressed to pneumonia they would be hospitalised and in some cases, particularly the eldery or vulnerable, they would die. This is still happening today, but the whole process has been co-opted and rebranded by authoritarians to serve ulterior motives, and the public are to shallow to realise this. Now a whole industry has grown up around the deception (from the lowest covid marshall to the Big Pharma executive) and so many jobs rely on keeping the deception going its going to be very difficult to steer the great covid tanker around to get it heading back to where we started..

SAGE and the modellers were already proved wrong this summer and autumn when their predictions about “Freedom Day” were spectacularly wrong.

And many times before that really. They have exaggerated and got it wrong every single time.

What makes anyone think this is the one that would discredit them?

If this crisis has taught us anything is that reality, data and facts don’t count for anything any more. Only power does.

Stewart,

I have been a “Man made Global Warming” realist for well on 40 years. Every single one of the warmists predictions have failed to materialise.

This does not stop the majority of rulers rushing to return the world to cavedwellers by destroying civilisation.

Science is ignored and fortunes are made with lies and propaganda.

Sadly this Chinese flu hysteria is just the second chapter of the scam, and I cannot see any sanity returning in the short term.

So enjoy Christmas, it could be our last.

Funnily I said that to the wife while putting an extra bottle of wine in the trolley and spoiling my self with some rum. ‘This could be our last Christmas’. She gave me a funny look and went to find some cranberries.

Covid will be over come spring/early summer.

Political attention will then zero in on NetZero and the costs are becoming clear. Assuming Boris is still around, there are a lot of back benchers gunning for him already. He would have been long gone were Starmer any good as opposition leader.

Thanks to covid, Boris has little time left to do much about NetZero before immediately facing a general election. He can’t face one with energy prices spiralling out of control and any recent history of black outs etc.

Then there’s China, India and Russia which are clearly not interested in climate change, and even the media are beginning to squeak about that. Biden is having a torrid time over his proposals and his personal position also looks unstable.

Now the green blob, of all people, is up in arms in Australia about wind turbines being built on undisturbed land.

Europe has slapped 19% import tariffs on Chinese made turbines which is not being received well and will impact badly on the cost of commission them, which will be subsidised with Taxpayers money, and the Taxpayers will notice that.

Sales of electric cars are not even close to what is required to meet any emission targets our government has set, despite the subsidies, which our Taxpayers are also beginning to notice.

Finally, there’s the cost of covid which we have no choice but to repay. We have a choice with NetZero.

I agree – I think that they want to ultimately deter people from celebrating christmas – stop the publicans and restaurateurs gearing up for it and offering christmas do’s after this years have mostly been cancelled and stop people making christmas plans by keeping the whole “will family gatherings be banned?” thing on a knife edge until the very last minute.

I am convinced it is deliberate. Religion and christianity, what are left of them now, do not suit the purposes of what is to come.

Well, and we now know that SAGE and the modelers only produce the models and results the politicians ordered.

Stewart, but, to take but one example, Professor Pantsdown Ferguson’ career for around a decade has been one of incompetent computer gaming ‘projections’ using highly improbable assumptions, in order to generate shroud waving and doom mongering.

He’s made a career of it.

That was well understood when he was picked for SAGE. And HMG also knew that “Stalin’s Nanny” Michie was a long term Communist Party of Great Britain Central Committee member. She was appointed and still permitted to piss both out of the tent and from outside the tent (Independent SAGE, the BBC), pissing in.

No worries, no complaints. Imagine the brouhaha if someone had suggested perhaps Tommy Robinson should be appointed…

I’ll believe Chairman Boris ZeDonkey realises he has blundered when, instead of printing more money, he starts printing P45s for those who have led or promoted this scam from the start.

Don’t hold your breath.

They predict the ‘worst case’, and the ‘worst case’ rarely happens. The worst case for a aircraft flight is a total crash and burn. That is so incredibly rare that people don’t even think about it. Almost all flights are totally inconsequential, delays excepted. The ‘most likely’ outcome of any flight is a perfectly normal uneventful flight.

Get SAGE to model airline flights and see what they can do to the airline industry …. oh wait …

Good analogy.

If Johnson holds his nerve he can destroy the argument that he should have “locked down earlier and harder”. If he holds his nerve he can Chuck every last one of Sage etc under a bus. Hopefully Rees Mogg getting off his charge yesterday will harden his resolve to hold the line!!!

What has Rees-Mogg done?

“Borrowed” a fortune against his company and been found by the bould Kathryn Stone to have done nothing wrong.

Ah ok, so you’re saying the him being let off will inspire the PM to see sense?

Reports suggest Rees Mogg, whose fortune is predicated on accurate financial modelling, was the man who really laid into Vallance over the pessimism of the modelling. Just heard some prick modeller on the wireless admitting that the “cases” aren’t rising “exponentially” which he says is down to change in behaviour, etc.

Rees Mogg has been pretty quiet so far and voted with the govts fascist shit every time. Be interesting if he turns.

Follow the money.

Down to change in behaviour – so how does that work, does the virus keep a list of who’s naughty or nice? Do these people really believe the carp they churn out? I’m expecting news presenters to start rolling their eyes when they read this stuff out, it’s becoming so predictable and lame.

I wonder why he did that?

Financial crash looming?

I am quietly hopeful

But, I expect the doom-mongers to say any plateauing of the ‘outbreak’ is due to the doom-mongering causing people to change behaviour – and that we will need lockdown in January to avoid a surge when ‘everyone comes rushing back to work’

Even Owen Jones!

Now we are truly a lost cause as that brain dead little shit weasel is wrong about absolutely everything so if he’s on our side……

He realizes and accepts that public opinion has turned against them, but his solution is to throw more money around to the little people and the beloved NHS and do them regardless.

Not really a convert.

Jones is the ultimate weather vane. Very loose and easily moved by the slightest breeze.

Talking about South Africa, here is an interview of Nick Hudson, founder of PANDAS. The clarity of thought exhibited in this interview is wonderful to hear. For example, his explanation of the motivation of the global elites neatly bridges the Toby/James divide and should really become the position of both.

https://odysee.com/@TLAVagabond:5/NIck-Hudson-Interview-10-7-21:1

I’ve got everything crossed that you’re right Toby.

“not least because senior members of the Cabinet are actually pouring over real-world data for the first time instead of just reading SAGE’s memos.”

If, true (and I don’t doubt it) that is an absolute disgrace. These Ministers are supposed to challenge the Experts and if they have just been meekly accepting the garbage produced by SAGE they have failed the country and are not fit for purpose.

There’s only one thing which will stop Johnson imposing more moronic restrictions …. and that’s the fear of an ever greater rebellion by CON MPs and the possibility of another Ministerial resignation. He’s a coward ….. but a coward who wants to stay in No.10.

Meekly accepting garbage is par for the course – it is exactly how the US Task Force operated under Fauci and Birx (chaired by VP Pence) last year, according to Scott Atlas.

A disgrace, yes. But perhaps a hopeful sign that they now see the writing on the wall and are repositioning themselves to escape blame “well, until Dec 2021 it looked like ….., but now things have changed …..”

Ideally we want these b******s strung up (metaphorically, I assure you) but first, we have to break the cycle.

Bozo is caught between a rock and a hard place. If he gets booted he loses his sinecure, he won’t be popular inside or outside the party and a wilderness beckons.

Bliar has made a fortune but only via wholesale treason. Is that where Bozo is headed assuming the Davos mob will even have him?

I am not for new restrictions however I cannot understand waiting to bring them: if it is that serious, why the wait!

I mean really why?

On a separate note, my husband is going to his family on Christmas Day. I will be with an elderly parent who is alone.

His bloody sister ( think this warrants a mild expletive) wants him to take an LFT test. I despair I really do- if she’s that worried just cancel!!

But that’s not the best bit: she wants him to take it when he’s ALREADY at her place!!

That’s right he is expected to make a 2 hour journey + petrol only to be presumably sent home if it’s positive on Christmas Day!!

I had to be put my foot down on this: a compromise has been reached where he takes one before he leaves.

I’m now working on talking him out of it as there’s no effing way I’m losing out on Christmas at her bequest.

Her initial suggestion was nuts. So nuts I’m actually asking you good people if indeed there IS sense to it that I’ve missed.

Probably so that she can see for herself that he actually took the test, and what the result really is. Her demand makes sense in the paranoid and divided/divisive world of covid, a world in which she doesn’t trust her brother to tell her the truth about covid-stuff.

That makes sense, thanks.

I ‘d thought that myself but, of course, he still has to be sent home if it is positive AFTER he’s actually met people at her’s.

He wouldn’t lie, anyway.

I think she wants to call Christmas off really and he doesn’t particularly want to go so I’ve suggested he just use omicron as an excuse.

Where did she want him to do this test? Outside, before he was even allowed to enter the house? If not, it makes even less sense!

Yes, it is unhinged behaviour.

No covywovy – you’ve missed nothing – your partner’s sister is unnecessarily concerned.

All any test does is to indicate whether someone might have SARS-CoV-2 which can be present in someone who is not necessarily ill and infectious with the disease – Covid-19. In your partner’s case, if he has no symptoms, even if he tests positive on arrival, he won’t infect his sister as he won’t have anything like the required viral load to be infectious. Slice ‘n dice it every which way, if he feels fine when he sets off to his sister – she’ll be fine. The one caveat is that if he’s staying any length of time and there are other guests at his sister’s house, he could catch if from one of them or develop symptoms if he caught it not long before setting off. If he’s just there for Christmas day, his sister has absolutely nothing to fear from him. Furthermore, unless she’s elderly and/or has a comorbidity, the only thing she’s infected with is fear itself; the virus presents minimal danger to her as her chances of survival if she caught it is well in excess of 99.7%!

There is a bigger dinner party on Boxing Day. But he has actually suggested to her that he leaves early on Boxing Day. She said no to this so go figure.

I’m still annoyed, though.

These LFT’s are not particularly accurate and I believe that people should either just go ahead and enjoy Christmas free of Covid- related stuff or just cancel it if they’re that bloody bothered.

Taking LFT’s on Christmas Day for heaven’s sake!

Is this a class thing? They’re very, very middle class – betcha working class and upper class people won’t be taking LFT’s on Christmas Day!

Disclaimer: I am NOT saying ALL middle class people are like this but the ones who WILL be taking LFT’s on Christmas Day are.

Hold on. He’s chosen his sister over you? I’d pack him more than an overnight bag.

If you mean he’s chosen to spend Christmas with her as opposed to me, that’s wrong as he’s only really going to see his elderly mother.

We agreed all this months ago.If however you mean he’s meekly going to take an LFT test at her bequest thus ruining my Xmas for no good reason if it happens to show positive but he’s asymptomatic you may have a point.

Not forgetting the isolation period.

I’m beginning to hate this woman.

I don’t see why he can’t leave on Boxing day morning, though! His sister says no! It should be his decision, should it not?

He’s happy to stay.

“I’m beginning to hate this woman.”

Join the club – my partner’s two daughters and their husbands are Covidiots too. It’s usually people you knew to be not very intelligent who have fallen at the first hurdle, those who have questioned ‘Covid’ from the beginning seem to be more intelligent. There are many well-written and coherent posts on this site, for example. I don’t believe such intelligent people are all ‘mad’ and ‘conspiracy nutters’. Some take it too far (nanobots in the vaccines!) but many keep a level head and have sussed that ‘Covid’ is a con.

Well if it’s anything to go by this woman would be perceived by many to be extremely intelligent. A graduate from Oxford University no less.

I’m not really sure this is about intelligence though: more about an inherent wisdom.

I think there are 2 kinds of intelligence. The ability to learn and the ability to think clearly and see through the mist of irrelevant/false information. The more the world is bombarded with this information the fewer in number clear thinkers become.

The whole woke culture thrives on this mist. Which engulfs some very clever learners. They don’t have the clarity of thinking to see through it all.

Same here, a sibling with PhD from Cambridge who wears a mask even when not required, is jabbed, and is worried about OhMy.

I think that a lot of conventional success stories, professional and/or academic, have jumped through so many hoops, had to think a certain approved way etc, that literally cannot question this sort of thing. Very sad and shocking.

I also find it’s often the ‘highly educated’ who think they are too clever to accept there is a conspiracy occurring.

I’m predicting my SIL will insist on LFTs for Christmas Day.

My response will go down well I’m sure….

I’d tell her to get lost. If she’s that bothered, she should just cancel – as should every Covid paranoic.

These LFTs are all Made in China. Nothing quite like continuing to hand the Chinese all our money! Thanks for The Virus, China!

The importers of the LFT tests are those who need to be looked at.

China will probably only get 10% of the cost. The rest will disappear in markups by the interminable list of insider middlemen.

I think I have to agree with you – I think there is a class element to it. Worried, hand wringing middle class people who don’t want to be accused of “doing the wrong thing” or even worse, breaking the law, are taking the ‘testing’ approach.

I have written on this issue before. The relative hosting christmas this year for my family has issued an edict in the invitation that all attendees must do a LFT that morning and only attend if they test negative. I have no intention of doing a LFT as I think it is A) a scam B) likely inaccurate anyway C) absolutely DISGUSTING – it is small wonder there are so many people sick if they are constantly sticking those swabs around their tonsil area and then UP THEIR NOSES – ewwwww and D) I have a deviated septum so it would be positively dangerous for me to try to stick any kind of swab up my nostrils.

I’m not going into this with them – I’m simply going to lie and say i tested and it was negative. I take 4000iu of vitamin D every day, a gram of vitamin C and on days where there might be more risk to me [than I would likely pose to others] from being in close proximity to a lot of double and triple jabbed people I take quercetin. My daily diet is rich in good quality fruit and vegetables and is highly nutritious and well balanced – far superior to that of the seriously obese host who contracted a bad case of covid and then followed it up by getting jabbed.

Another relative’s christmas plans lie in tatters because of a positive LFT in another member of their party despite the fact that she travelled a long way to join the other guests.

I think the whole thing is utter madness.

In days of yore, colds and flu (remember them?) would be in circulation at this time of year. If you were highly symptomatic and unwell you didn’t attend a gathering. The idea that people’s christmas festivities should hinge on the outcome of a highly dubious LFT or PCR is just another ruse so that the testing contractors can make more profits and the little people can be further controlled.

I would imagine that working class people who have possibly invested a lot of time and money which they have had to save up and set aside to fund their celebrations wouldn’t let their plans be derailed in this way. They would likely assess the ‘risk’ and go ahead.

The wine and cheese parties in No 10, both last year, and in May 2020 did not, I imagine, hinge on the outcome of a LFT or PCR test. And that was when the covid ‘pandemic’ was supposedly at its height, unlike now with the Omicron variant which is so mild people do not even know they have it. I rest my case.

We’ve allowed a generation or two to grow up thinking the world revolves around them.

Until people asking for unreasonable things like this start to lose out on income and life nothing will change.

It’s time the Nervous Ninnies were sent to their room and excluded until they find some strength in their spine.

Yup.

Why wait? It’s all political theatre, has been from the start.

Hubby needs to grow a pair and tell his sister where to get off. She has the effing nerve to tell HIM how to run his life. His bloody sister. Not you his wife.

Grief.

Seems perfectly reasonable to me

There’s always one. Lol.

I’d love to believe you’re right Toby, but, this site being for sceptics ‘n all, I’m a tad – well – sceptical! The following comment was posted btl by Jon Garvey on another article a few days ago, and it’s one we would be wise to keep in mind when deliberating how this might all play out over the coming weeks . . .

“As Sarah Knapton pointed out in the Telegraph today, the death figures are bound to rocket, if Omicron harmlessly infects millions, because of the way that Covid deaths are defined (within 28 days of positive test), and the normal death rates at this time of year – she quotes 0.9% usual death rate for January.

If a sizeable proportion of the population gets Omicron, many thousands of deaths will get falsely assigned to the Covid deaths by definition. You could have zero Omicron deaths (not too unlikely) and still have the worst pandemic winter on record.

The only saving grace would be that excess deaths wouldn’t be that high, and the non-Covid deaths would plummet. But you can bet your life Whitty and Co would forget what they knew about excess deaths and pandemics in 2019.”

I fear this is a more likely scenario and Prof. Lockdown and his fellow doomsters at SAGE will finally have a prediction that comes good.

Agreed that will be a difference compared to say South Africa which is having it in summer.

They would count as ‘with’ not ‘from’, which the UK regime has already acknowledged in their desperate attempt to find an omicron fatality – grudgingly noted as ‘with’, not ‘from’. Vaccine status inferred to be fully dosed up on the grounds that an unvaxxed status would have been just what the covidians want and would have been shouted from the rooftops with no concern for patient privacy. ‘Patient privacy’ these days, like ‘national security’, is the first refuge of the scoundrel.

Italy had a similar proportion of ‘from’/’with’ as the UK and has officially, but quietly, downgraded its covid fatality count to about 10% of the earlier figure. Too late of course.

Any excess deaths will more likely be the result of ADE but attributed to Covid and whatever the current flavour is.

This comment sat on the Telegraph website for the best part of yesterday and crept up the list of ‘most liked’ until it was taken down for violating their rules. I was expecting it to last no more than five minutes – hence the screenshot. Hold the line guys. Truth shall prevail and we shall be victorious. Happy Christmas one and all.

What I want to know is why was it taken down?!

“It never happened, and even while it was happening, it never happened.” Harold Pinter on propaganda during during his Nobel Literature prize acceptance speech.

Amen to that

I have heard it is already done and dusted

I have felt this for the last few weeks too, just being out and about, seeing more non compliance with mask wearing, old folks not caring a hoot in supermarkets as they squeeze by you to grab the last punnet of blueberries, it just feels like people are no longer terrified. There are still those of course who have it well lodged in their nature and psyche, the snide Benjamin Butterworth types who just enjoy telling folk how to behave, the virtue signalling Esther Ranzten types who just know better and the angry fat shouty middle aged man types like James Whale and that John Gaunt fella, who has lost his mind, and is sadly just terrified. When I see these folk on TV now they are starting to sound like delusional extremists, they really are not sensing the mood of the nation. One of my most zealot lockdown loving, rule following, triple jabbed, kid jabbed friends told me the other day that even she was running out of steam and couldn’t face another lockdown. We are reaching the end of this road.

yes and no – I’ve seen the same in supermarkets (trains too), but went for a wander round the town centre yesterday evening and it was absolutely dead – some of the pubs and restaurants hadn’t even bothered to open, and those which had only had a handful of customers. No way normal for a few days before christmas.

Very true, it is not at all like Christmases past, but to see as many folk in Glasgow town centre not wearing masks is really something, compliance has always been near 100%. Plus I just have this feeling in my bones, 2022 could be our year

Tesco at 5am this morning and i didn’t see any other non-mask wearers. Which i’m afraid has been typical round here, even though no one, member of staff or public, has ever challenged me. Maybe because i tend to go very early in the morning, the shoppers are the terrified because they think they will be ‘safer’ then as there will be fewer people around.

But masks may now just be an easy sign of conformity for people and they are becoming more willing to ignore other restrictions quietly and behind the scenes.

M&S, and probably Waitrose, are ground zero for the mindless zombies and wannabe fascists who would sell out their neighbour / relative to the Brownshirt Covid Police.

The people on the front line actually working/delivering goods etc know it is BS (M&S staff wear masks only ‘cos some fscking masked Karens complained). The top level know it is BS because they are running the show. It is mostly only the pampered pandered mediocrities who fall for the BS. The ‘not wanting to rock the boat’ / ‘be different’ aspects also play a big part, thoroughly exploited by the Nudge Unit (aka SPI-B).

Check out the #Waitrose hashtag on Twatter. Especially “blue tick” Simon Day (him from off of The Fast Show). Ironically, his bio is “Do not live in fear” https://twitter.com/simonday

The figures for deaths in care homes show a sudden sharp rise in England in week 17 of 2020 (week ending 26 April). Then deaths fell and rose again in the winter of 2020/2021.

From The Exposé:

Beds occupancy in NHS hospitals for the periods of April to June in 2017 to 2020 inclusive:

In the April to June period in 2020, at the height of the SARS‑CoV‑2 “pandemic”, bed occupancy in NHS hospitals was down 30% when compared to the same period the previous year. NHS bed occupancy was also down about the same percentages when compared to the same periods in 2017 and 2018.

Visits to NHS A&Es for the periods of April in 2018 to 2020 inclusive:

Attendance at A&E in April 2020 was down a whopping 57% compared to the same period the previous year.

But yet figures show that deaths of old people in UK care homes took a sharp rise at the very same time that the NHS bed-occupancy work-load decreased by 30%, and the A&E workload decreased by a whopping 57%.

An alarming footnote to this is that a directive was sent out on the 19th March, 2020 to the NHS which required them to discharge all patients who they deemed to not require a hospital bed.

(The link will bring you to a page that informs the document has been removed because it was out of date. I’ve included a screen-grab of the original document below, thanks to The Exposé. But how on earth can any authority issue a directive and then after the event claim it is out of date?)

Follow this link to hear Matt Hancock confirm on video that the government had a “big project” in place to source drugs like Midazolam. Also, note the psychopathic countenance of Dr Evens in the video – if ever an actor is needed to play Josef Mengele, Evens would fit the bill fine.

Directive to vacate hospital beds. Hospitals and A&Es at least busiest for years. Large numbers die in care homes at the time hospitals are less busy than they ever were. Matt Hancock confirms to a psychopathic looking Dr Evens that large quantities of horse-strength sedatives are on the way.

I really don’t think there is any option but to go with Occam’s razor on this one.

However, to keep perspective,it is worth bearing in mind that there has always been a problem with discharging fit patients from hospital beds, and the use of A&E for non-serious complaints.

That said, the proposed framework for discharge is unrealistic IME.

Over the past couple of days I’ve seen a number of Covidians using this to try to justify their locktivism:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1043095/COVID-19_Data_Briefing__21_December_2021_.pdf

Particularly the graph on page 13. Has anyone analysed the data behind it to see what this actually shows in reality – i.e. which of the many definitions of ‘unvaccinated’ is in use, what proportion of those are already so ill with something unrelated that they can’t be ‘vaccinated’, etc…

‘Vaccinated’ is a political status, not a medical one, though those exploiting it pretent it is purely medical.

pandemic, case, infected, cause of death, vaccine, vaccinated – all words that now mean whatever the Queen of Hearts wants them to mean, varying as needed to suit the desired outcome.

Agree – but try telling that to a BBC news swallowing total covidian. They believe that those words actually still mean something now.

The idea that a ‘case’ might be no more than a fraudulent positive test result is just totally beyond their comprehension.

Very frustrating.

100% agree with Toby here and but Johnson may hedge and throw in a token gesture like shutting sports stadiums, rather than fully reject the doomsters. That may keep the Tory mp’s quiet. Anything can happen the PM is an imbecile.

The chain has been broken by prior immunity the fact that Faucism rejects. Our Health secretary Mr Malteser Head is a disciple of Fauci. That could be the biggest problem of 2022 and the MAIN reason people won’t get injected is they have already had the virus and in that case the experts you can trust expect immunity to last a long time from CCP Virus.

“Or Boris could just look at the actual data.” – the only figures he’s interested in are those on his Cayman Islands and Swiss bank accounts.

Anyone care to predict how 2022 is going to go? I think it’s going to be much of the same, only by next Christmas the adults and fossils will be on their 5th jab, and the 12-18 year olds will be on their 3rd jab. The 0-11 year olds will also get jabbed during 2022.

By December 2022 people will still be wearing face masks in shops and on public transport, and people will still be testing themselves often to see if they’ve got lucky with ‘The Virus’. There will be a new ‘variant of concern’ wheeled out this Spring, and maybe another ‘mutant strain’ to add more mayhem during or after Summer.

Protests may still be allowed as it allows people to let off steam – the Police know protesters turn up around 1230pm and go home four hours later, and they have everyone on file anyway. Internet discussion forums will be even more tightly controlled and people will have to be very careful about what they post for fear of ‘the authorities’ come knocking on their door.

Let’s see if I’m wrong. All a bit grim, but look around you. I remain hopeful that things will get better, but at the same time I have to look at the reality.

How much tat have we bought Made in China for Christmas? …is that a sort of “Thanks for releasing SARS-CoV2 onto us!”

Unless there is quiet push back.

Which there won’t be as the vast majority of people have swallowed the propaganda.

I’ve said before that the Government and SAGE can have even more of a laugh once they’ve got so many people hooked on these ‘vaccines’ in order to keep their ‘vaxx passes’ valid. All they have to do is invent a ‘technical problem’ and ‘shortage’ of vaccines… say, the 5th Jab… and watch the people scramble to get one!

Fisticuffs outside the NHS Jab Centre! The surveillance cameras can feed directly to the televisions at Downing Street and SAGE headquarters. It will be like the Romans watching gladiators, only a bit more like this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g2Rt-1hfbA

All of this presupposes that Johnson and his chums are sensible. But they’re not. They’re fanatics.

I think some of them are becoming more sensible according to reports of Cabinet discussions. Others are fanatics. As for Johnson, i think he is just ‘a reed shaken by the wind’.

AEP nails it

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2021/12/23/prof-lockdowns-apocalyptic-omicron-claims-undermine-faith-vaccines/

“Academic etiquette restrains direct criticism, but immunologists say privately that Professor Neil Ferguson and his team breached a cardinal rule by inferring rates of hospitalisation, severe disease, and death from waning antibodies, and by extrapolating from infections that break through the first line of vaccine defence.

The rest are entitled to question whether they can legitimately do this. And we may certainly question whether they should be putting out terrifying claims of up to 5,000 deaths a day based on antibody counts.

“It is bad science and I think they’re being irresponsible. They have a duty to reflect the true risks but this is just headline grabbing,” said Dr Clive Dix, former chairman of the UK Vaccine Task Force.”

“Dr Clive Dix, former chairman of the UK Vaccine Task Force.”

Former chairman? Easy to say these things when you’re not working there anymore!

The ‘Good German’ defence.

At least he opened his gob and had a go.

I know it’s not directly related to the article but what is the basis of the claim that 9/10 in hospital with Covid are unvaccinated?

Also headline in the mirror claiming it’s young people dying in hospital who are unjabbed. Really??

More importantly, why do the jabbed care if unjabbed die? Why don’t they have the same zeal for “saving” the obese or heavy drinkers or drug users from themselves and from taking up valuable NHS resources?

Why do the jabbed mask wearers care if I’m wearing a mask? If they at triple jabbed and have a mask on (should be ffp3 if they are really scared but is usually what amounts to a soiled pair of pants) then they are protected.

The other good one is obese smokers dutifully replacing their mask after inhaling tar!

A particularly stupid step relative of mine is in favour of concentration camps for the unvaccinated, smokes and has been hospitalised several times with asthma induced pneumonia….

A cousin of mine, a keen motorcyclist, follows the Piers Morgan and apparently mainstream dogma that the unvaccinated should be refused hospital treatment. I told him while sitting beside him at dinner that he and people like him should be hanged from the nearest tree.

And then hopefully also told him he would not deserve hospital treatment, as he had, most definitely, brought it upon himself

A very polite and considered response.

Read Will Jones’s article on this yesterday (Dec 22) it’s titled No, the NHS is not being overwhelmed by the unvaxxed, and he goes into this 9 out of 10 claim in some detail. I haven’t seen anything about unvaxxed kids dying. Maybe they have other major health issues and that’s why they havent had the vaxx?

It all depends on the meaning of ‘unvaccinated’ Today’s vaccinated are tomorrow’s unvaccinated.

Ah, but the thing is, the ‘data’ coming from S Africa is ‘real-world’, and inferior to actual Data derived from the Computer.

In the same way, natural ‘immunity’ is a quaint, but out-moded belief, that some still harken to. The abundantly clear reality, however, is that true immunity can only come by way of Synthetic immunity.

They are also a younger population so we have to be very scared still. Come on keep up

That’s right.

Science is useless, unless it is genuine THE SCIENCE lovingly purchased (with your money) by HMG.

Policy based Evidence making at its finest.

The Anti brexit EU gravy train riders have been strangely silent, for quite a while now, are they on the Jaboree gravy train now, where tax payers money is being redirected from services, including the NHS, to be used to buy jabs, ppe, testers etc, to solve the nhs problem one way or the other.

Covid mania is imposed by Brexiteers.

Just a fact to counteract imaginary assumptions.

Sigh. There you go again Rick. What silly, silly nonsense.

I suspect that your feelings about the covid havoc pales to insignificance compared to your apparent absolute contempt for the crime (as you probably see it) of Brexit.

Your ‘fact’, that: “Covid mania is imposed by Brexiteers.”, is just deranged obsessivenes.

Shame we left the EU – if we had stayed, we clearly would not have to suffer covid mania. As a Leave voter, please accept my sincere apologies for playing any part in the resultant Brexit-induced covid mania.

Still, one more thing to blame on Brexit I suppose.

FF’S!

This article is predicated on the belief that all actions so far have been motivated by a concern for the nation’s health. Unfortunately, the last last 20 months haven’t been about health.

The economy has to be flattened – expect another lockdown.

Look at us in South Africa. We have had zero changes to our so called lockdown measures which as it stands consists of a midnight to 4am curfew and masks in shops (believe me when I say 80% of the population ignore those rules anyway). The case numbers went up very fast and they are coming down very fast. We probably have about 30% vaccination rates who mainly consist of the same middle class who have been the only ones obeying these restrictions for the last 20 months. The majority of the population have no interest in vaccines or any of the rules imposed on them. Our medical advisory council seems to have finally agreed that the whole testing, tracing and quarantining of people is a waste of resources and must be stopped. I went to a big schools provincial tournament last weekend and the rules and regulations that they were trying to follow lasted about 24 hours by the time the finals arrived the venue was packed to the rafters with most people having given up on all the masks and other rituals of the terrified class. I sense it is over here you guys just need to realize that for yourselves.

All this confirmed by my friends and family there. I should’ve joined them.

You should its still an amazing place to visit especially the Cape.

I agree – beautiful. Spent quite some time in Cape Town when I had family living there for a few years. I’d happily move if you guys could keep up what you are describing [covid over] and I could live there. Staying in UK isn’t very palatable the way things are going.

confirms my post above Jock – it is a middle class conformity/anxiety thing.

Just had to post this…says it all.

The funnier version has “Free Coffin”.

That’s not the funnier version, that’s the true version.

And there is nothing funny about it. It means that all the people I love will be gone.

Do you know what alw, sadly this isn’t far wrong – based on the latest UKHSA study published in the MSM today, where booster effectiveness ‘wanes’ after 10 weeks and they announce that they intend to maintain “flexibility” over the booster programme, that means a booster 3 times per year minimum (until the PHE is declared ‘over’, scheduled for 2025 based on current info). Wonder if people who decide they don’t want to be ‘boosted’ that many times, for a cold, should look into ivermectin.

The positive rate for test results is not going up so how can Omicron be spreading at all? The increased cases are just becausevof increased testing aren’t they?

Always have been. Testing asymptomatic people with an imperfect test is guaranteed to produce a pseudo-epidemic. This is a well kmown phenomenon.

I see a massive epidemic of asymptomatic broken arms. I just happen to have a test for this condition. It isn’t perfect, but is good enough. A 4lb lump hammer. The amazing thing is how often people develop symptoms after being tested. I’m sure that is evidence of the value of the test, catching people just before they become symptomatic. I am sure with the right marketing, this could save the NHS millions.

“debunk irrational nonsense in the media with your incisive comments below the line”

Thank you for the encouragement – but it probably isn’t needed!

Thank you to all contributors both above and below the line for providing a beacon of light over the course of this diabolical period.

The current battle may be turning in our favour but there is still an awful long way to go before we can say we are winning the war.

This is probably not the beginning of the end so much as the beginning of the middle.

At least China was right, at the start they said this would lead to people falling down dead in the streets, on the sports fields and on live TV.

Should have never doubted them…

People falling down dead in the street, with a film crew in place at exactly the right moment. Colour me sceptical.

Western MSM presentation

The bigger picture

Tank man was stopping the tanks leaving theTiananmen Square, not entering it.

Merry Christmas everyone.

And I don’t care what Johnson and his cronies say, I will be meeting friends and family throughout the festive period and indeed I may even party like it’s 1999!

good for you – have a good one!!!

call me cynical, and frankly I think I am now the biggest cynic on the planet, I think we are all being treated to a bit of a Christmas pantomime. If we look at Johnson’s political situation he is on the skids, with a possible leadership challenge in the New year. He needs something to save him. So, why not send out all the little demons (sorry advisors)to spread fear and doom and gloom regarding anothe Lockdown in January, Will he do it? Oh yes he will, oh no he won’t etc. Then in January he will show strong and decisive leadership against Satans little minions and say NO, we will not heed you, we will carry on, Omnicron is not the plague. The back benchers will jump for joy, they will claim that Boris has been brought back to life, the media will love him once more. Primeminister Johnson will remain and the confected Omnicron will be put back in the cupboard for a feww weeks until Mr Johnson needs to bring out a new scariant round about February.

I agree. We are being played.

We have been played since Day 1.

As I said to my equally sceptical son this morning, next year there will be a new film released, “Boris saves Christmas”

Boris saves Christmas – only a year too late!

Still, better late than never…

Without sounding flippant, ” the end of the world is nigh ” could become a reality if… Russia, China or Iran made a bad mistake of lobbing nuclear weapons around Even a conventional war in Ukraine, Taiwan or Iran/Iseral would cause millions of young lives.

Russia has no need to invade or ‘lob nukes’ into Ukraine. The Ukranian military was once part of the now-defunct Warsaw Pact. Russia knows where all the weapons stores are (it still has serial numbers of anti-aircraft missiles supplied prior to the end of the USSR), what the stores contain (weapons sold to ISIS aside), where the fuel stores are, the routes of the secure comms lines, the secure bunkers, the airfields, the logistics centres, locations of the US outsourced bioweapons research labs (all 16 of them), etc, etc. It fired Kalibr cruise missiles 1200km from the Caspian to ISIS targets in Syria with ~100% target strike rate. The most distant part of Ukraine is ~900 km from Crimea. Ukraine can be trashed militarily without Russian ground forces having to leave their bases 100’s of km from the border. The shreyed invasion is a Ukranian/NATO wet dream.

Yes listen to the data please Boris, but also…don’t! Because what are we saying if we advocate that the degree of restrictions we accept should be proportional to the severity of the variant? We are tied into this nightmare forever!

There should be no restrictions placed on our lives in order to help the NHS. The only incentive to staying healthy should be good health. I don’t even care about the so-called “spread”. If people are scared then they can stay home or wear PPE.

As for Boris, it makes no difference if he “holds his nerve”. Respiratory infections will peak in the UK in the 3rd week of Jan, the same as they do every year, and he is on his way out whether it’s for imposing new restrictions too late or never.

I hope that someone behind the scenes is already planning which of the Covid Recovery Group members has the best shot at a leadership challenge. Is it too late for me to join the party so I can vote?

I’m still waiting for the photographic expose of the sage Christmas parties that most likely happened last year.

There must be tons of examples of Ferguson, Vallance, Michie, et al, breaking their own rules.

Constantly showing Pfeffel breaking their rules concerns me that it is an effort to replace him with someone who’s more strict. That’s certainly the direction the corrupt MSM have been going.

I rather hope the government, SAGE and the rest of them go on a two week bender, if they are all pissed or hung over at least they are out of the way and less likely to make decisions that might harm us. The photos can be used at a later date.

5000 deaths a day? So half a million over 3 months? The man’s insane, or he’s been sniffing something, any tool can see that “the virus” is relatively benign, unlike the actions of our government.

Quite frankly, the best use for SAGE is to mix them with onion and shove it all up the arse end of the nearest large turkey. At least we wouldn’t be able hear the incessant whining.

I guess I am very slightly optimistic. We might take some comfort from the fact that ministers are now demanding hard data. Also, apart from mad Nad and Javid, who has fallen under the fatal mesmeric control of the NHS, the cabinet are more sceptical.

At the moment, however, I think our gratitude should go to thise Conservative backbenchers who voted against plan B. Johnson is wary of being a Tory leader with a big majority who needs continually the support of Starmer’s pusilanimous Labour MP’s to get something through the house.

Further, the mood of the country is changing. Many in my experience who previously went about with a ‘keep safe’ in their heart and a mask on their lips now openly questioning why, when the country is jabbed up to the eyeballs this shitshow is still going on. Why Whitty, Ferguson and their ilk still keep appearing through the floor like the Demon King in a Pantomime with graphs of insensible woe.

We can but hope that scales are falling from eyes.

I was in a large and absolutely packed city centre German-themed bar/restaurant yesterday. I was sitting next to a large window looking onto a main pedestrian thoroughfare to the Christmas markets. It was really interesting to see how many muzzled morons were coming up to the window to observe that life was completely back to normal inside. What must have been going through their addled minds to see a bustling warm environment full of cheery people living their lives. The expressions on their faces weren’t disapproving, they just looked completely confused. On either side of their route they would have seen a heaving Christmas market (despite the wet weather), and a full Christmas ice rink. Seeing something like that when the telly has been telling you there is a deadly plague has got to eventually get through the layers of brainwashing.

As for scales falling from eyes – yesterday we met up with brother in law and wife in a pub for lunch – we haven’t seen them since this nonsense started. We noticed as we drove through their Leicestershire village people were masked walking in the street!! We walked into the pub unmasked as were the staff but everyone who came in were wearing masks until they sat down, including brother in law and wife. He took off his mask and put it on the table I said ‘they don’t stop you catching a virus you know’ – he never replied – so whilst some may see the light others will never do.

“He took off his mask and put it on the table “. That about says it all. You take off a rag soaked in bacteria from mouth and nose and put it on the surface you are about to have plates of food and cutlery placed on. Food hygiene 101 – not. How many people are getting ill from precisely this sort of stupid behaviour. Who needs the “killer” covid to fill the hospitals..

I would love to believe that might be a possibility for the tide to start turning. However just like before each previous lockdown was a political decision to cover up the social economical disasters of Brexit and corruption in the government isn’t it?! Every single one of them … so at the moment Boris government credibility with all “leaked” media stuff is not looking that great is it?! So perhaps once more lockdown will be used to crank up fear once again and deviate once again the public from what is really going on. But coming January 2022 and the collapse of financial market… the pocket of many will be truly felt…. Then Covid or not people will feel across the world …. Where things really hurts… the pocket with no money!

The next step ‘may’ help prove that this is about the virus or something far more sinister. Interesting time.

I recommend Robert Kennedy’s latest book on Fauci – lots of useful information in it and one which made me sit up more than others was Fauci took his lead from Ferguson’s computer modelling! And there you have it!!

Fergusoon et al,. have always played a leading role in all this. The largest contingents to WHO meetings have always been from the UK.

A lockdown sceptical tune (with a US focus). Hold the line fellow amazing lockdown sceptics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7KFjB51p7o