What are the world’s worst inventions? Winston Churchill famously regretted the human race ever learned to fly. I don’t (I’m looking forward to my next holiday too much). Instead, observing the destruction wrought by government pandemic responses predicated upon projected Covid cases, I’m beginning to regret mankind ever invented the computer model.

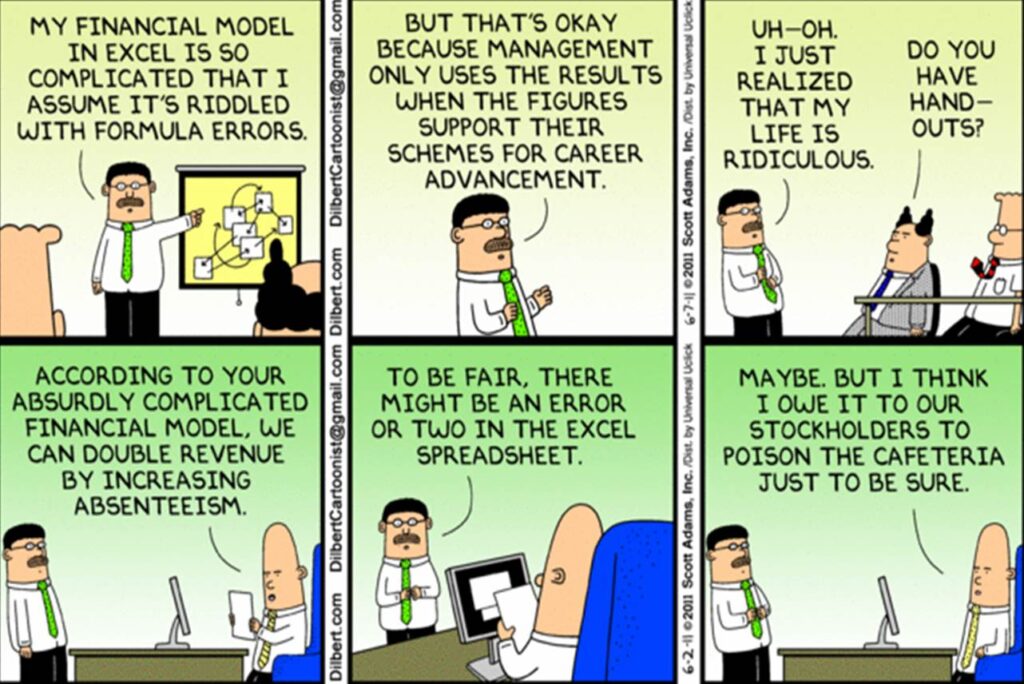

I have form here. I spent the early years of my career building financial models, hunched over antique versions of Excel on PCs so slow the software might take twenty minutes to iterate to its results – which, once received, were often patently wrong. I developed a healthy mistrust for models, which frequently suffer from flaws of design, variable selection, and data entry (“Variables won’t. Constants aren’t,” as the saying goes).

Models allow outcomes to be presented as ranges. In business, it’s often the best-case outcome which kills you – early-stage companies typically model ‘hockey stick’ revenue growth projections which mostly aren’t realised, to the detriment of their investors. In pandemics, though, beware the worst case. In December, SAGE predicted that Covid deaths could peak at up to 6,000 a day if the Government refused to enact measures beyond Plan B. The actual number of Covid deaths last Saturday: 262.

SAGE’s prediction was its worst-case analysis, but the fact that the media (and then the Government) tends to seize upon the worst-case is nothing new. In 2009, Professor Neil Ferguson of Imperial College, to his subsequent regret, published a worst-case scenario of 65,000 human deaths from that year’s swine flu outbreak (actual deaths: 457). As Michael Simmons noted in the Spectator recently: “The error margin of pandemic modelling is monstrous because there are so many variables, any one of which could skew the picture. Indefensibly, Sage members are under no obligation to publish the code for their models, making scrutiny harder and error-correction less likely.”

The worst-cases of Covid models have proven to be the equivalent of shouting fire in a crowded theatre – politicians have often found these projections impossible not to act upon. As an aside, being caught in an actual fire in actual crowded theatre is more of a problem than you might imagine – not only for the obvious reason, but also because the design of the entire fire response, from the moment of activation of the sprinkler systems, to the anticipated heat of the fire, to one’s egress from the building, will all have been forecast by potentially highly inaccurate computer models. A 2007 Edinburgh University study compared the modelled results of a fire in a two-bedroom flat in Glasgow with an actual observed fire. Projections of fire temperature varied, hopelessly, from about a 45% over-prediction to about a 90% under-prediction.

As volatile financial markets try to digest the competing themes of inflation (caused by pandemic effects such as supply-chain shortages and soaring energy costs) and long-term deflation (caused by the relentless impact of new technology on working practices) it’s worth recalling that some contemporary economists believe the standard Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models employed by every Central Bank to forecast the economy are fatally flawed. Not a single Central Bank DGSE model predicted the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, for instance.

Models of the kind used to predict epidemics, economies and fires are complex, sui generis beasts – Neil Ferguson’s Imperial model was 15,000 lines of C++ code, written over the course of a decade. Yet the most misused form of model remains the computer spreadsheet – the kind of model I used to build in the early 1990s, of which Nassim Nicolas Taleb noted in The Black Swan:

Things changed with the intrusion of the spreadsheet… Once on a page or on a computer screen, or, worse, in a Power Point presentation, the projection takes on a life of its own, losing its vagueness and abstraction and becoming what philosophers call reified, invested with concreteness.

The ‘correctness’ of spreadsheet models has proven fatal: research has found that over half of spreadsheets used in business are materially faulty. In the 2007-8 Global Financial Crisis, one problem was that spreadsheets contained the prices of rarely-traded Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs), which were pools of mortgage bonds whose prices had not been updated to reflect the highest rate of mortgage delinquencies in 13 years. Prices contained in spreadsheets became ‘reified’ – and over-depended upon – until price discovery finally blew the models and the banks up together.

Indeed, spreadsheets are so famously unreliable that there is an organisation, the European Spreadsheet Risks Group (EuSpRiG) dedicated to tracking their many failures (sponsors include Imperial College). A recent spreadsheet mistake is Public Health England’s failure to report 16,000 UK Covid deaths, thanks to the use of an obsolete Excel file version with a limit of 65,000 rows of data, rather than the current standard of one million plus rows.

It would be easy if we could simply disparage models and modellers as hopeless and ban them. Sadly, models are not reliably unreliable, either. Sometimes they prove highly reliable. A 2020 NASA study compared 17 increasingly sophisticated model projections of global average temperature developed between 1970 and 2007 with actual changes in global temperature observed through the end of 2017. The majority of the models turned out to be correct, with forecast and actual temperature changes not materially different. And for all my early travails with spreadsheets, models make money for many practitioners: a hedgie friend tells me he could never leave his current job, since the code within the models he successfully uses to predict price relationships would remain the intellectual property of his current firm and could never be replicated.

Winston Churchill might not have predicted that flying would become the safest form of transport. Perhaps he would be less surprised that killer drones are the latest form of modern warfare. As for models, the key will remain differentiating between good and bad models and modellers. Not easy to do. But a hint: if Professor Neil Ferguson is involved, be careful.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpMacron Says, “No Vaxx, No Citizenship” as France Unveils New, Stricter Vaccine Passports

Next PostLessons From the Pandemic