Regular readers will remember Philippe Lemoine from my interview with him back in August. For those who missed it: Lemoine is a PhD candidate in philosophy at Cornell with a background in computer science. During the pandemic, he’s written several interesting articles, including a particularly good one titled ‘The Case Against Lockdowns’.

Lemoine’s latest article is a zinger. It begins with the puzzle of why the effective reproduction number often fluctuates wildly in the absence of changes in aggregate behaviour. Or put another way: why do infections sometimes start falling, or start rising, for no apparent reason?

I actually noted this puzzle myself in article back in March (which Lemoine kindly cites). Specifically, I noted that case numbers in South Dakota began falling rapidly in mid November, despite almost no government restrictions and little change in people’s overall mobility.

There are at least two existing explanations for this phenomenon. The first is seasonality: the effective reproduction number may partly depend on variables like temperature, humidity and UV light. Yet as Lemoine points out, there are many examples where case numbers changed suddenly that seasonality can’t explain (like South Dakota).

The second is viral evolution: the effective reproduction number may suddenly rise when a new, more-transmissible variant emerges (such as Delta or Omicron). Once again, however, case numbers have undergone dramatic changes in the absence of new variants. And while viral evolution can explain the rises, it has harder time explaining the falls.

Lemoine’s explanation is different: population structure. Traditional epidemiological models, he notes, assume the population is ‘quasi-homogenous’. This means that your chance of infecting someone of the same age who lives next door is the same as your chance of infecting someone of the same age who lives on the other side of the country.

Not very realistic, of course, but models have to make simplifying assumptions. How much does this one matter? It matters a lot, Lemoine argues.

Rather than assuming there’s one big quasi-homogenous population, imagine the population is divided into a large number of ‘subnetworks’. These could be based on location, age-group, behaviour or a combination of factors. For example, one subnetwork might be ‘school children and their parents in central London’.

Suppose that transmission occurs frequently within subnetworks but infrequently between them. So when a child within the school subnetwork catches the virus, it quickly spreads to other children and their parents. But what it doesn’t do is quickly spread to those outside the subnetwork.

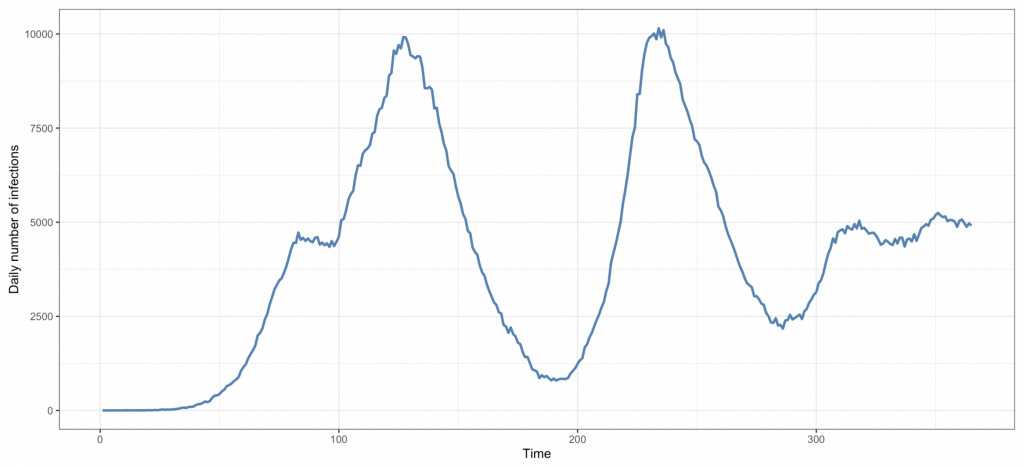

Lemoine shows using simulations that, if you assume the population is structured in this way, the reproduction number can rise and fall without any changes in seasonality, viral evolution or aggregate behaviour. One of his simulations is show in the chart below.

Compared to the giant single-peaked graphs produced by Imperial College researchers last year, it’s a much closer fit to empirical data. The idea is that once the virus exhausts all the susceptible people in one subnetwork, it takes time for other subnetworks to be seeded, and for new epidemics to emerge.

One interesting implication is that the overall epidemic ‘wave’ is actually the sum of waves in all the subnetworks where the virus is currently spreading. This means that several quantities we’ve been obsessing over, such as the effective reproduction number, might be “largely meaningless” at the aggregate level.

When infections start falling in a particular country, the Government often takes credit for having ‘gotten the R number below zero’. But if Lemoine is right, the R number may have fallen simply because the virus exhausted susceptible people in the subnetworks were it was recently spreading.

So governments may have been taking credit for fluctuations in the R number that were entirely independent of their policies.

Population structure is by no means inconsistent with other two explanations I mentioned earlier: seasonality and viral evolution. And although it’s hard to test empirically, the theory seems eminently plausible and worthy of consideration. Lemoine’s article is over 17,000 words, but it’s worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Oh dear, never mind.

That photo is a good metaphor.

It exploded because it was the hottest day evah in Wales….

Just the wrong type wind which is the fault of Jim Dale.

The wind turbine has a conscience at least.. ——-Unlike the handwringing squirming parasite Net Zero people.

Windkraft nein danke

That turbine probably produced more net energy (which was wasted) by burning and exploding, than it supplied to the grid in its entire operation.

Love it.

Just as well that there has been quite a bit of rain recently.

I wonder if it’s because the turbine was kept operational in high wind speeds and overheated, rather than being shut down as a lot of turbines are when it’s too windy.

I bet none of the clowns in the CCC have considered the fact that turbines can’t operate safely in high wind speeds in their assessments of how much renewable capacity and backup we’d need to achieve net zero.

The 3 ( now only 2) turbines at Blaen Bowi are fairly small 1.3MW devices with hub height at around 46m ( 150 foot) They have massive disk brakes to stop the turbine at wind speedsover 25m/s. Brake failure and overheating through trying to stop a rotor around flammable olis in the nacelle has seen quite a few turbines off. Fire is second only to catastrophic failure of a blade. The cost of lost generation revenue and subsidy often exceeds the relacement cost of turbine due to 200-300 days manufacturing lead time

I’d be slightly worried that the fire service can’t reach anything that’s only 150 foot off the ground.

Or did the just let it burn for other reasons? Perhaps “I’m not risking my neck for the useless thing let it burn?”

Mid and West Wales Fire Service said:

“Pieces of the wind turbine were falling nearby and crews monitored the condition of the debris.”

It looks like it’s phooked to me.

I agree. It’s definitely firked.

Oh, without a doubt. Totally Tom Ducked.

It’ll never blow again. Absolutely tatered.

You gotta larf…😀😀😀

They weren’t pointing and laughing, hp. This is serious. They were MONITORING the CONDITION of the DEBRIS 🤣

I suspect the firefighters at the scene were pointing and laughing and for all I know making TikTok videos. It’s the Press Office that invents official prose and perhaps the Chief Fire Officer who has to keep a straight face at a press conference while reciting the Official Narrative.

😀😀😀

I think the phrase you are struggling to f-find is “unscheduled rapid disassembly”.

Much appreciated 😀

Can we give the designers the contract for ULEZ cameras and 5g masts?

Yes who are the designers and makers and suppliers of these cameras? We should name and shame the companies and boycott them if possible.

Subsidised Wind Solar Wreak Economic Havoc –

leaflet to print at home and deliver to neighbours or forward to politicians, media, friends online.

This is by far the most effective way to get heat from a windmill. I hope many more of them suffer a similar fate.

So they ARE good for something. Now all the Eco Nutters have to do is find a way to harness the energy they create when they’re burning.

Indeed, whilst at the same time trying to find a way to offset the carbon emissions from the combustion. I think the Germans once referred to incinerators as a means of Thermo’ induced recycling, or something like it.