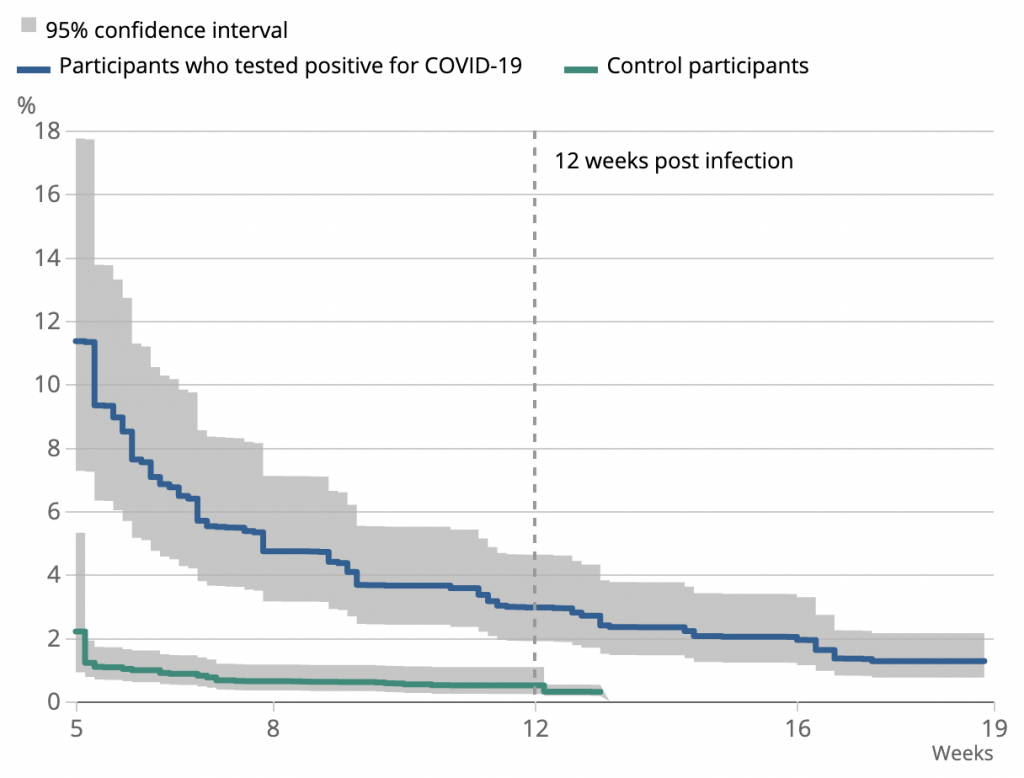

In a post on long Covid back in July, I said that “estimates of the chance of reporting symptoms after 12 weeks range from less than 1% to almost 12%”. That 12% figure came from the ONS, who found that individuals who tested positive were 12 percentage points more likely than controls to report at least one symptom 12 weeks after infection.

In my post, I argued that 12% is probably an overestimate on the grounds that some people who tested positive might have been inclined to exaggerated their symptoms – to report things they normally wouldn’t have done (thanks to all the media attention on long Covid).

And I noted that a study published in Nature Medicine had observed a much smaller percentage of people still reporting symptoms 12 weeks after infection, namely 2.3%.

A new analysis by the ONS has obtained a figure almost identical to that observed in the Nature Medicine study, namely 2.5% (the difference between the blue and green lines in the chart below). This is clearly much lower than its previous estimate.

Interestingly, the reason for the discrepancy with the earlier figure isn’t the one I suggested (i.e., that some people who tested positive were inclined to exaggerate their symptoms). Rather, it’s a statistical issue.

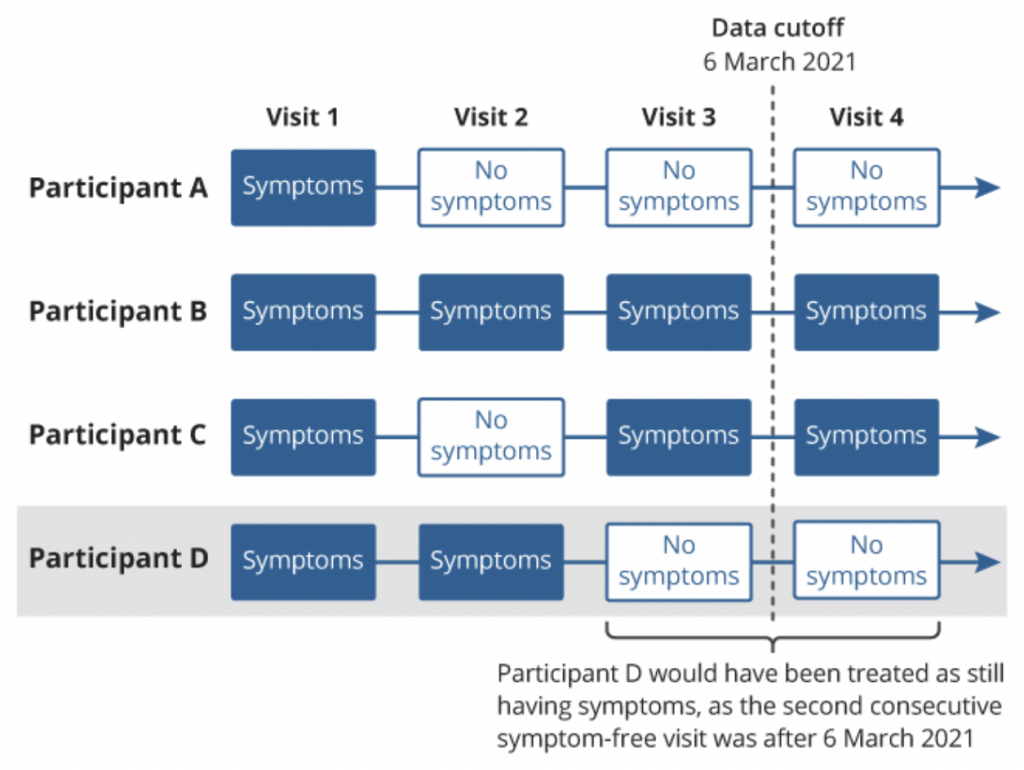

In both their original and updated analyses, the ONS defined symptom discontinuation as two consecutive visits without reporting any symptoms. (Participants in the ONS’s survey were visited at regular intervals for the purpose of data collection.)

This means that someone would be classified as ‘having symptoms’ if they’d gone one, but not two, visits without reporting any symptoms. However, in their original analysis, participants were only followed for a median of 80 days (less than 11 weeks).

As a result, some participants who would have been classified as ‘not having symptoms’ if they’d been followed a little bit longer were still classified as ‘having symptoms’ at the end of their observation period. (In the jargon, their follow-up time was ‘right-censored’.) This is shown in the diagram below, taken from the ONS:

In the ONS’s updated analysis, which followed participants for a median of 204 days, individuals in the situation of Participant D above were correctly classified as ‘not having symptoms’ before the end of their observation period.

Using this revised method, the ONS found that less than 1% of children aged 2-11 continue to report symptoms 12 weeks after infection, with the figure rising to just 1.2% for those aged 12-16. Hence long Covid is particularly rare in children, further undermining the case for vaccinating that age-group.

While the ONS deserves credit for being completely transparent about the limitations of their original analysis, their updated analysis is still open to the criticism I mentioned above. This means that 2.5% should probably be considered an upper bound on the chances of getting long Covid, the true figure being somewhat lower.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

no, “long” covid is a made up fantasy

As soon as a Covid zealot loses the debate regarding the lockdowns, they raise the ‘issue’ of long covid. Fails every time, because it’s horse s**t.

Long Covid is just a re-brand of Post Viral Syndrome. Can we stop parroting the propagandists attack lines please?

It may be post viral syndrome but what causes it? The original pathogen or some other reason, such as reactivation of herpes family viruses? Herpes viruses remain in the body in a latent state for life, they can be reactivated by stressors, think recurring cold sores or shingles.

I’d put it down as a form of scarring. When you are damaged you don’t necessarily get back everything you had before.

To me, it’s a combination of the scaremongering making people scared, plus a person’s general health (including mental) and that having a virus will inevitably drain you. Most people will lose weight via not eating much whilst the immune system uses energy to fight off the virus.

I remember getting the flu (and after getting vaccinated) REALLY BAD back in Sept 2013 – even as someone (around 40 back then) who isn’t overweight, has average fitness but who at the time was under a lot of stress at work with a long commute, I was off work for 2 full weeks, but even when I returned to work, I was severely drained for at least a couple of weeks afterwards. I lost at least half a stone in weight.

I suspect it could be far worse (and longer) for those in poor health and/or who are suffering from severe stress generally.

The problem is that most people have never had proper flu. If you get it you are ill for months.

I had it in my early 30’s back in the 90’s, i wouldn’t want to catch it now.

Apart from the terrible fevers of the first week, the loss of sense of smell, taste and hearing lasted months, followed by bronchitis, i think it took at least three months to get over it.

I had a test a few weeks ago that confirmed what i suspected, that i had covid this time last year, apart from a severe sore throat and sneezing fit and extreme tiredness for around ten days that was it. Then i was type 2 diabetic and 3st overweight. I wonder if my body remembered the flu from the 90’s ?

PS I have lost the weight and have now reversed the type 2. I bitterly regret taking the jabs now and will not have the booster(s )

But how could the test know you had covid when no one has isolated it yet (and likely never will)? If these so-called variants are different enough to require a third jab, surely that makes it even more difficult for these tests to find what it is looking for?

My advice is to not take anymore tests. Remember that every time you test positive, you’re supporting the covid fraud.

The BUPA test does not show anti bodies from existing vaccines:

Whilst the Bupa COVID-19 antibody test can show if you have detectable antibodies as a result of having had COVID-19 infection, it will not show antibodies produced in response to vaccinations currently given in the UK, and should not be used for this purpose

Canada elections today folks. Another one goes down into totalitarianism (zero opposition parties), joining the ranks of Australia/NZ. RIP Canada

Didn’t Pantsdown do another model on Long Covid? How’s that looking now?

Whose idea was it to have ‘long covid’, can’t imagine anyone pondering on ‘covid’ until they came up with that one.

sounds like a BBC thing.

good article in TCW https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/the-collaborators-paris-1941-and-london-2021/

Long Covid is just total bollox

“Long Covid Is Even Less Common Than Previously Thought”

I never thought it was common

Its normal to feel rough after the flu

Your not keeping up ! What about short covid, you know the one a some time US president had and was back at work in two days…

Given that “symptoms” include self-reported annoyances like fatigue and given that the participants of the study were not blinded (to do it, you’d have to lie to them about the test result), all the numbers are basically subjective crap, the only thing studied is “how more likely are people to become hypochondriac when told that they tested positive for the purportedly terrible new disease”. And using the same flawed logic you can go to VAERS to “find out” how many people reported “symptoms” after the “terrible new gene-therapy-based vaccine”.

It’s no surprise to me that people still feel tiredness, etc after a viral infection, given it often is associated with periods of low physical activity, eating less and general sickness.

Made worse when so many during the last 18 months have barely done any (more) decent exercise, especially in the fresh air. Apparently the average person is now more unfit and overweight than before the pandemic, even amongst non OAPs.

Given how much time many people have had on their hands as they are either being furloughed, working from home (and thus have the extra commute time free) or just not working, but with at least an hour (unlimited time since June [?] 2020) a day for outdoor exercise in addition to being able to walk to the shops etc for provisions, you have to wonder what people have been doing for the past 18 months.

Indeed, being barred from preferred aerobic exercise for several weeks/months is already enough to start feeling fatigue. One of the reasons people feel less inclined to exercise is the feeling of doom and gloom. Depressed people tend not to move around much (which feeds back into their depression). Some also resort to compensating with other unhealthy habits like drinking or “comfort” (crap) food. Can’t really blame them because the reason for the misery is an outside factor beyond their control. Of course, feeling no control over your life/future (most increased by the “shifting goalposts” or outright refusal to promise a definite end of the restrictions by their tormentors) is yet another factor that increases likelihood of depression.

Exactly. It’s a vicous circle. I bet sales of chocolate, alcohol and fizzy drinks boomed in 2020. Even worse when Christmas was cancelled.

The process of producing antibodies is tiring. For the elderly, anyway.

I’ve contacted the Worldometer people several times now because they have consistently been underestimating/reporting the number of ‘recovered’ people in the UK on their updates – despite the ONS saying for some time that the number of infected (mid estimate) is around 900k and falling, the Worldometer figures still say 1.3M and often rising.

They did, back in the spring, update those figures (after I reported a similar problem) when our New Year ‘surge’ came to an end – they lopped off several hundred thousand ‘infected’ in one day. Sadly they are now ignore my similar (polite) requests to do the same now.

That this article shows far less people are liekly to be faced with post-viral issues (as often happens when people come down with a viral infection) shows that so-called ‘long COVID’ and actual infection rates are significantly less of a problem than the so-called ‘experts’ boldly predicted would happen.

Note that despite the English schools being back for 2 weeks now, infection rates in England (bar a few ‘usual’ trouble spots [we all know where]) are still dropping week-on-week and have been lower than those of Wales and especially NI and Scotland for some time now.

I. Can’t remember the name of it, but you can have tiredness and long term symptoms from other viruses too. It’s exactly the same as that! Long covid… what utter bullshit!

Covid certainly isn’t as long as the hysterical authoritarianism we are being subjected to in its name. There’s no vaccine to protect us against that.

There is no such thing as ‘long covid’, since C19 doesn’t exist in the first place.

I came to the conclusion that the Daily Sceptic promotes tons of errors and inaccuracies; it pretty much looks like a ‘controlled opposition’… if you know what I mean.

Post-viral fatigue? Anyone?

Probably very similar numbers to those pre-COVID hysteria hypochondriac numbers for the common cold or flu. Man flu? Who hasn’t had one of those colds (man flu) that just won’t go away for weeks and weeks?

Long Cold/flu? or sometimes a bit more dramatically known as a ‘Post Viral Syndrome‘.

“Long Covid Is Even Less Common Than Previously Thought”

So we’re actually Short on Long Covid then?

I’ll get my coat…

Waffle and Crap: The vaccines are “Kill Shots” and nothing else – you have had them, this is your fate:

Dangers of Booster Shots and COVID-19 ‘Vaccines’: Boosting Blood Clots and Leaky Vessels

New discoveries in the immunology of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 vaccines

What happens inside your body after injection with gene-based COVID-19 vaccines? How does this new ‘vaccination’ technology differ from usual vaccination methods, and why is that dangerous?

In this document, we answer all those questions and more, based on the latest and best available science. We explain how several papers in 2021 significantly advanced our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 immunity, and therefore the science and safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 vaccination programme has followed a policy of ‘vaccinate first – research later’, our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 immunity has only recently caught up with the rushed vaccination schedule.

Given that no clinical trials involved more than two injections of any vaccine, it is important that doctors and patients understand where the latest science leaves us in terms of how the vaccines interact with the immune system, and the implications for booster shots

.

We explain here that booster shots are uniquely dangerous, in a way that is unprecedented in the history of vaccines. That is because repeatedly boosting the immune response will repeatedly boost the intensity of self-to-self attack.

Please take the time to read this important information, and share.

The findings are presented in summary form for those who would like an overview, followed by an explanation of the underlying immunology for those who wish to understand in more detail.

https://doctors4covidethics.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Vaccine-immune-interactions-and-booster-shots_Sep-2021.pdf

doctors4covidethics.org

In January of 2001, I contracted a SARS infection. Spending days in the hospital and I have childhood Asthma. Following that, I developed a condition that was not understood in the initial stages of the health condition that later became known as ME or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. How alike are the symptoms of CFS/ME to Long Covid? Very alike and the evidence was seen that Coronavirus has been in the study and manufacturing stage since 2001 in the USA. My previous employment permits me to understand and have knowledge of many international ‘things.’ The origin of Covid 19 was originally in the US back in 2001. Look at the records of patents applied for in the USA between 2001 and 2003 for that evidence and two names appear CDC and Pfizer or the name as it was then. Was it just possible that CFS/ME was in fact possibly early evidence of manmade Covid infections. What is the prevalence of CFS/ME today, is it less registered in numbers or has it been replaced by Long Covid as the diagnosis? I suffered for about 12 years with ME, now I have symptoms of Long Covid, due to receiving both Vaccinations. I have developed additional health issues that were never observed previously in my body and they have appeared out of the blue but only after the first vaccination. Lord Stephen, Baron.

Drug treatments also almost eliminate ‘long Covid’ so no value in vaccination for this thin reason.