Back in January, when the lockdown was being put in place in Britain, I wrote a piece for this website trying to imagine future trajectories. I started with the assumption that, since COVID-19 is a respiratory virus, it would probably behave in the same seasonal manner as other respiratory viruses. Most notably, the flu. I called this “the flu hypothesis”.

Using this simple reasoning I then went and examined what different types of flu seasons looked like and used these to then discuss what government responses might be in the event of each.

Broadly speaking, I found two types of flu season. One I referred to as “gradual”; the other I referred to as “aggressive”. In the case of an aggressive flu season, cases tended to accelerate rapidly toward the end of December into January. These would then peak in mid-January and after that cases would burn out. In the case of a gradual flu season, cases would not accelerate quickly at all. They would creep up in early winter, rise a little in January and then either settle back down or continue to climb right through March-April.

Simply looking at previous flu seasons, I gave an estimated probability of an aggressive season of around 25-33% and an estimated probability of a gradual season of around 66-75%.

By the end of February, I had concluded that Britain’s COVID-19 season in 2020-21 had followed an aggressive path. It had accelerated quickly and burned out early. But given that the probabilities were what they were, if the flu hypothesis had anything to it, we should have expected some other countries to have gradual rather than aggressive seasons.

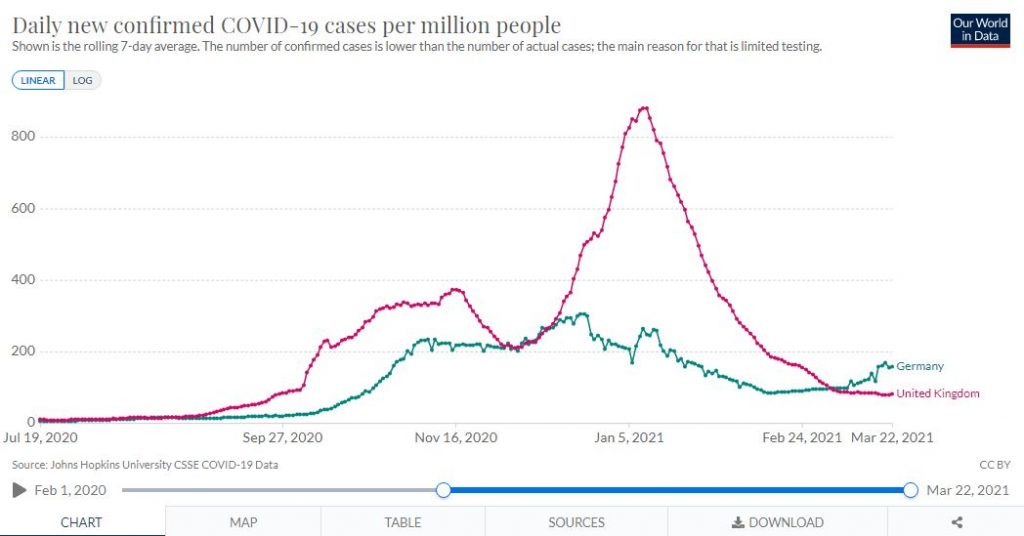

This, I believe, is precisely what we are now seeing in Europe. This week Angela Merkel announced that Germany was having a “new pandemic“. Her language was nothing short of hysterical. She said that a vicious new variant had arrived that was more contagious and more deadly. Looking at the data I cannot see it. It seems more likely that Merkel is trying to deflect blame. Europe’s rollout of the vaccine has made their politicians look incompetent relative to British politicians who were until recently portrayed as bungling due to their embrace of Brexit.

Politics aside, however, what is happening in Europe is interesting from the perspective of our flu hypothesis. This is because it shows the different policy responses to various types of flu season that we should expect moving forward.

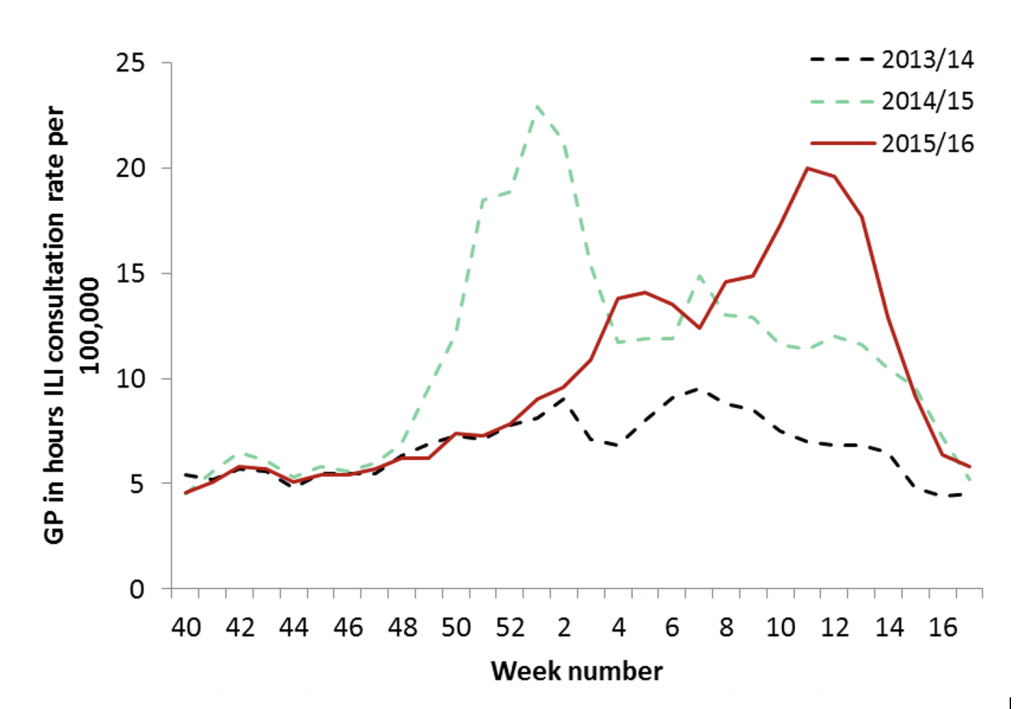

Here is a chart I have shared previously showing three different flu season patterns from Britain.

2014/15 is an aggressive flu season of the sort we saw repeated in Britain this year, albeit with COVID-19 playing the role of the flu. The other two patterns are very different. Now look at Germany relative to Britain.

Spot the similarity? Germany looks far more subdued than Britain overall. Yet while Britain is seeing cases taper off, Germany is seeing them rise again. It seems likely that this is simply due to Germany’s flu season following a more subdued pattern – perhaps like the one Britain experienced in 2013/14 or, if cases take off again in Germany in the coming weeks, like the one Britain experienced in 2015/16.

What are we to make of all this? For one, it shows the absurdity of flailing around trying to place blame on people and politicians for the trajectory of cases. Some things in life are simply random. Oftentimes bad results stem from bad decisions. But an awful lot of the time we experience bad results because we simply got unlucky.

One of the tragedies of the COVID-19 crisis has been that we have begun to assume that we have control over things that we do not. It is much more likely that the relative trajectory of COVID-19 cases in Germany and Britain was utterly random; yet we now think that we can attribute these trajectories to the behaviours of the actors involved. This is a form of magical thinking. It is incredibly primitive and if it was happening if a punter in a casino was basing his betting strategy on such thinking we’d take him gently by the arm and lead him away from the floor.

The problem with this sort of magical thinking is that it is also intoxicating. Merkel was overjoyed when Britain was seeing much higher case numbers than Germany. She could use it to bash the country over their incompetence and their rejection of the European Union. But now that the gods have turned on Germany, Merkel is hunkering down, engaging in scaremongering to deflect blame from herself.

Rare is the politician that is not seduced by powerful narratives. So, we can only assume that politicians will continue to ride the wave of randomness that COVID-19 has unleashed. It is becoming a sort of game. Rather than looking at poll numbers or GDP figures, the politicians stare at graphs of cases and deaths every morning – seeing what politicians always see: their own faces staring back at them.

They are trapped and we are trapped along with them. We may as well have convinced ourselves that they are in control of the tides or the weather. This is a game that no one should play because no one can win. Yet it is a game that is becoming more and more deeply embedded in our politics. We are regressing to a political primitivism at a remarkable rate. It will not end well.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpMore Than 200,000 Schoolchildren Currently Self-Isolating

Next PostHow Closely Does the Trajectory of the Epidemic in Each Country Resemble a Flu Season?