by Toby Young

Christopher Snowdon has now done what he failed to do in his original attack on lockdown sceptics in Quillette: he has engaged with the main plank of the sceptics’ case. Our central argument, as I explained in my reply to his article, is that lockdowns cause more harm than they prevent. I cited the wealth of evidence that lockdowns are largely ineffective, as well as the equally voluminous evidence that they cause social and economic damage. And I did my best to show that while some of this harm might be a ‘pandemic effect’ rather than a ‘lockdown effect’, the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) that governments have made across the world have exacerbated this damage.

In his response, Chris starts by making a pretty big concession: he acknowledges that the reduction in human interaction brought about by draconian stay-at-home orders could be achieved by people just deciding voluntarily to change their behaviour. He seems to think that lockdown sceptics are in denial about this – that we believe infections will rise and fall within a given region, irrespective of how much human interaction there is. Virus gonna virus. But I know few sceptics who believe that. On the contrary, we have been arguing from the start that the approach of the Swedish Government, which advised its citizens to take various precautions but didn’t force them to, should have been the approach of the British Government. Indeed, that was Boris Johnson’s strategy until he performed a U-turn and decided to plunge the country into lockdown.

The idea that the alternative to lockdown is to do nothing – that sceptics’ just want to “let it rip” – is a familiar straw man in this debate, and not just when Piers Morgan gets on a tear. In one of the most influential papers produced by the modelling team at Imperial College – known colloquially as Flaxman et al and published on June 11th – the researchers argued that the lockdowns in 11 European countries, including the UK, saved 3.1 million lives. But that claim was based on the assumption that 95% of the populations of those countries would have been infected with COVID-19 in the absence of any NPIs. Setting aside the fact that pre-existing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is almost certainly higher than 5%, it’s absurd to claim that people would have just carried on as normal in the face of a global pandemic if they hadn’t been ordered to change their behaviour by their governments. Indeed, this conception of democratic citizens – as mouth-breathing troglodytes who will march towards their own destruction without a benign state forcing them to act in their own best interests – is one Chris has objected to many times before.

No doubt Chris thinks this is a fatal concession on our part since if we acknowledge that voluntary social distancing measures work, how can we deny that involuntary measures work? Here, I think, Chris has misunderstood our argument. When we say that lockdowns are largely ineffective – largely, but not completely – we are not questioning the basic logic of germ theory. Rather, our contention is that the illiberal things governments across the world have done in an attempt to control the virus have not resulted in fewer people dying than if they’d taken a more liberal approach, i.e., one that respected our individual rights and our status as rational beings capable of carrying out our own risk assessments.

Why is that, given that lockdowns do reduce human interaction? As I said in my piece, it may be because they bring about a net reduction in overall interaction, but unintentionally increase it in particular hot spots, where the virus is more easily transmitted. Or it could be because the heavy-handed, authoritarian attitude of most states has infantilized their populations, prompting them to take less responsibility for not spreading the virus than they would have if they’d been trusted to change their behaviour voluntarily.

Could it be because few countries have stopped people going to supermarkets, which means herding them into enclosed spaces where social distancing is hard to maintain? Because lockdowns have meant people spending more time in their homes, where virus particles are less likely to disperse than in the outdoors? Because “key workers” are still leaving their homes every weekday, often using public transport? Because masks have led people to behave incautiously, even though the RCT evidence suggests they do little to protect the wearer?

These hypotheses may be wrong; but they do not require magical thinking, as Chris seems to think.

Chris is right when he says that the lockdowners aren’t alone in relying on counterfactuals – claims about how many people would have died in the absence of lockdowns being imposed. Our argument, too, relies on counterfactuals – we dispute the other side’s reasonable worst case scenarios and put forward more optimistic ones of our own. But we do have ‘controls’ in this argument – Sweden, which didn’t impose a lockdown in 2020, and those U.S. states whose governors have never issued stay-at-home orders.

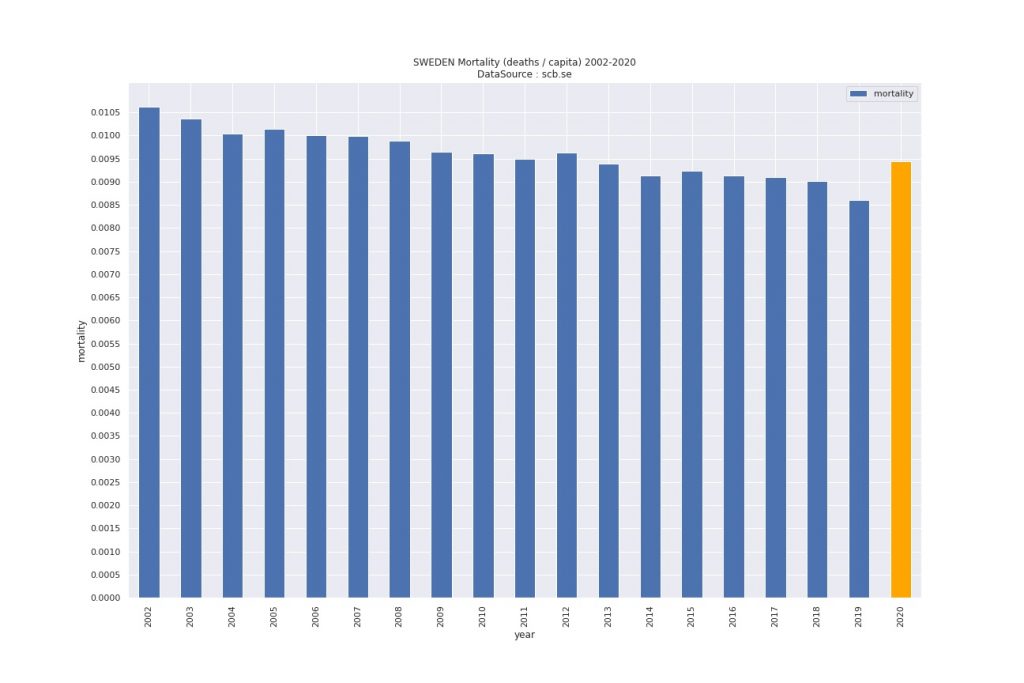

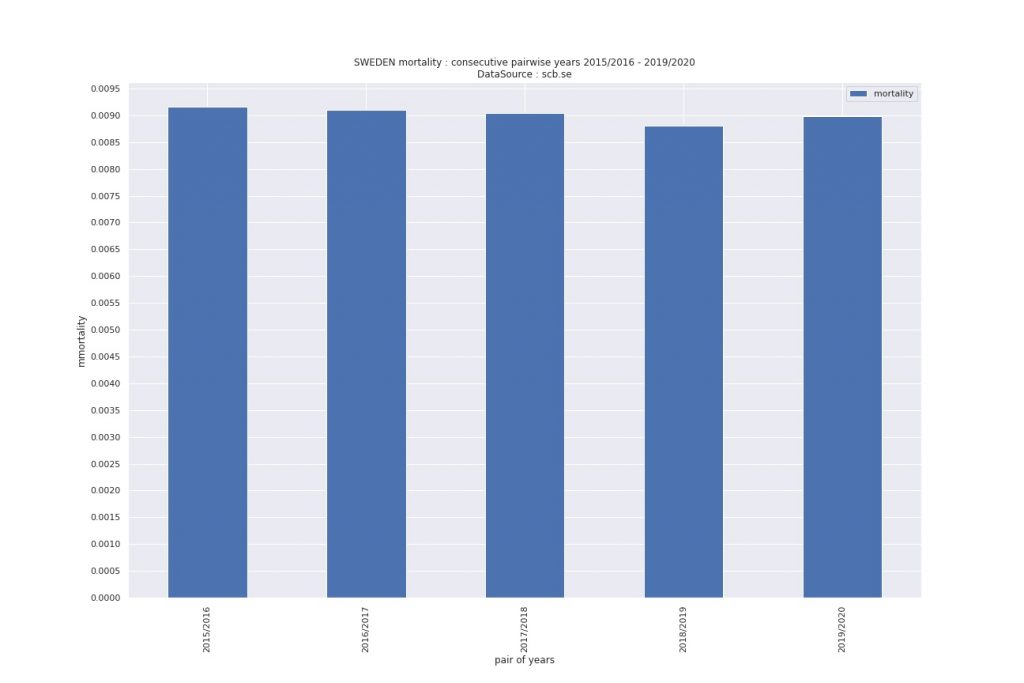

Chris neglects to mention Sweden, which is not surprising because it poses some very awkward questions for people who believe the Covid death toll in Britain would have been far larger if we hadn’t imposed two lockdowns last year. Yes, Sweden experienced excess deaths in 2020 that were above the five-year average – it experienced the highest number of deaths since 2012 if you adjust for population size.

But one reason deaths were higher than normal in 2020 is because they were unusually low in 2019 – the “dry tinder” point. If you combine all-cause mortality in 2020 with all-cause mortality in 2019, the total is lower than it was in 2017-18. (See this excellent analysis of Swedish mortality.)

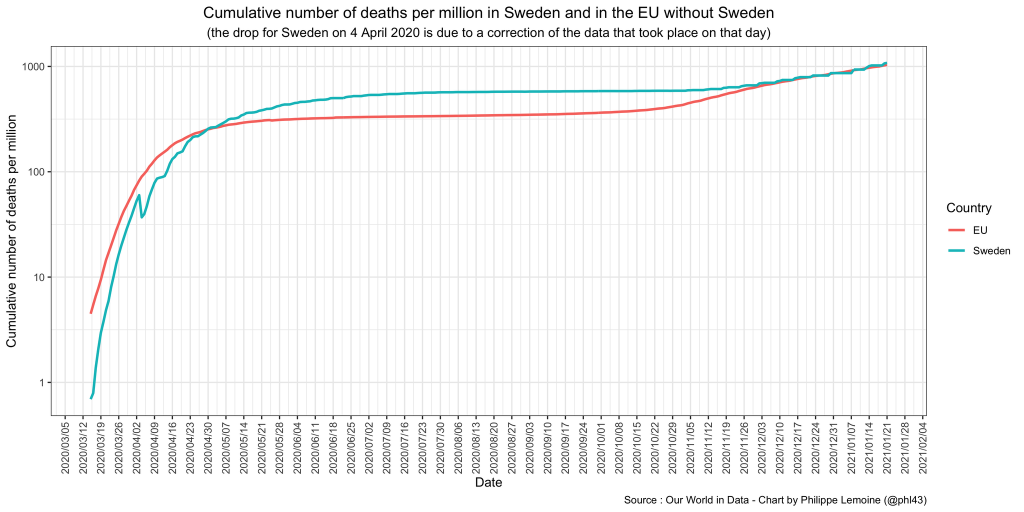

In addition, Sweden’s all-cause mortality in 2020, adjusted for size of population, was bang on the EU average.

If lockdowns are so effective, Chris, how do you explain that?

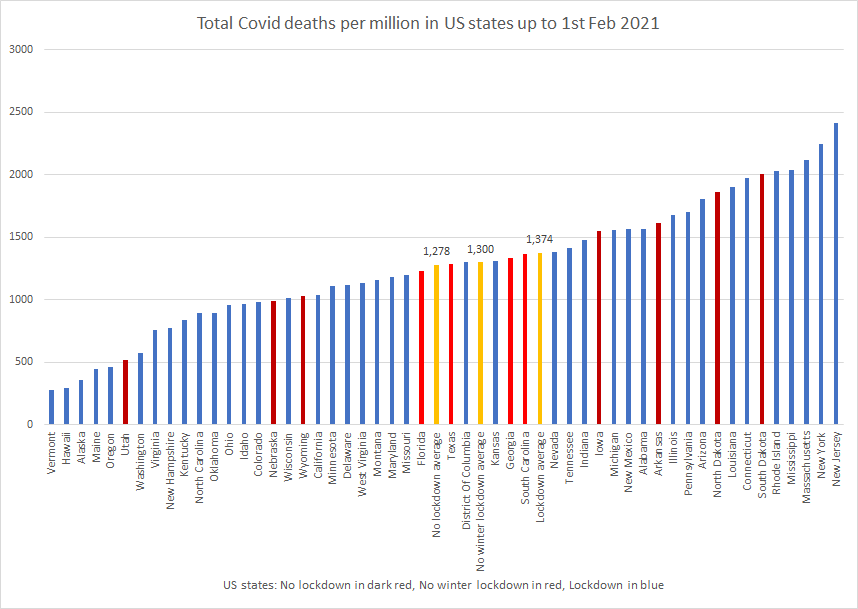

Chris does refer to the seven U.S. states that have never locked down – Utah, South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Wyoming, and Arkansas – and accuses me of cherry picking data by only looking at how they fared in the first seven-and-a-half months of last year.

By November, the pandemic in North Dakota and South Dakota was “as bad as it gets anywhere in the world”. Both states have an even higher COVID-19 death rate than the UK. Arkansas’s Covid death rate has risen from 21 per 100,000 to 166 per 100,000. Iowa’s is 160 per 100,000. Nebraska and Wyoming have a similar death rate to California, which is to say a high one. With the exception of Utah, all the ‘top performing’ states have seen COVID-19 kill at least one in a thousand citizens so far.

In fact, it’s Chris who’s guilty of cherry-picking. If you look at the number of Covid deaths per million in all 50 U.S. states up to February 1st, the average in those seven states is lower than the average in the 43 states that locked down. True, North Dakota and South Dakota are above average, but the top five are all states which issued stay-at-home orders.

If lockdowns are so effective, how do you explain that?

Chris points out that infections began to decline after lockdowns were introduced in autumn/winter in various European countries. (In the UK’s case, the claim that Lockdown 3.0 is responsible for falling infections is dubious, as David Paton pointed out in a recent piece in the Critic.) He admits that it’s difficult to prove this is causation rather than correlation, but claims that’s a more plausible hypothesis than the alternative – “that it is sheer coincidence that lockdowns have been accompanied by a sharp decline in case numbers in the UK and elsewhere time and time again”.

But I don’t know anyone who thinks this is “sheer coincidence”. Insofar as the decline in case numbers has coincided with lockdowns and other NPIs – and didn’t predate their imposition, as it did in the case of the UK’s first lockdown, which Chris more or less concedes – our contention is that it’s due to seasonality (which is why infections began to decline across Europe simultaneously last summer, regardless of when different countries lifted their restrictions) and the fact that the epidemic is beginning to settle into endemic equilibrium as more and more people get infected and then recover.

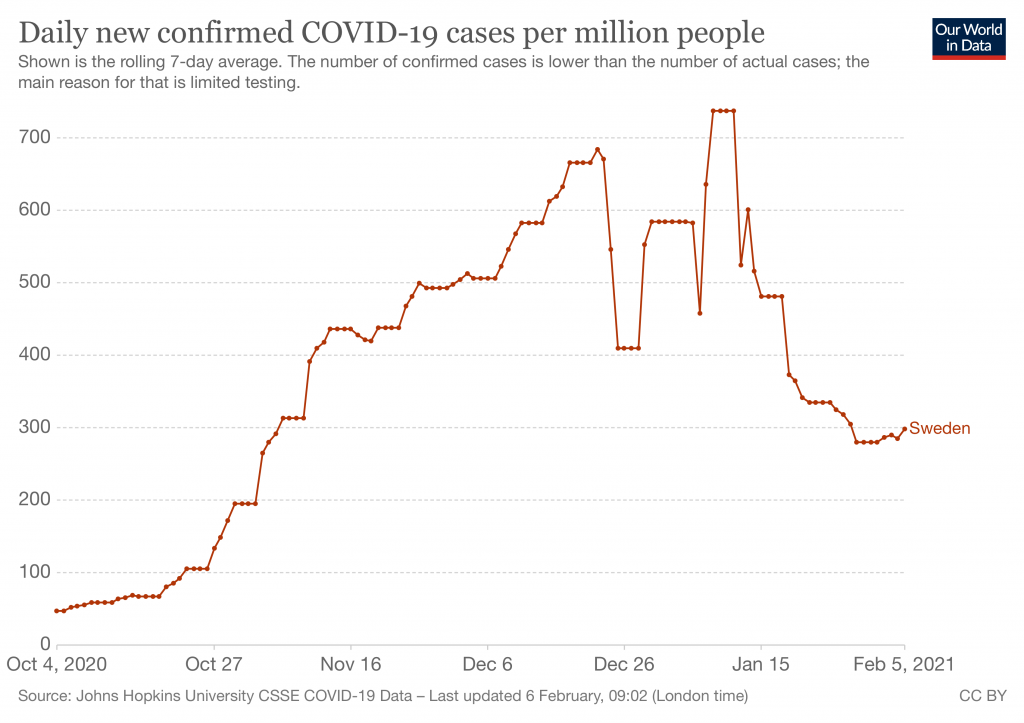

In support of the latter hypothesis, we can cite those European countries – including Sweden – where infections started to decline in January in spite of their not imposing lockdowns. Many lockdowners have leapt on the fact that the Swedish Government has had a change of heart, but the authorities have stopped well short of imposing a full lockdown. Restaurants, bars and cafes are open. Shops are open, including hairdressers and beauty parlours. Nurseries, primaries and some secondaries are open. Gyms are open. Household mixing is permitted. Face masks are not required. That’s a long way short of Lockdown 3.0, and yet infections in Sweden have been falling steadily since mid-January.

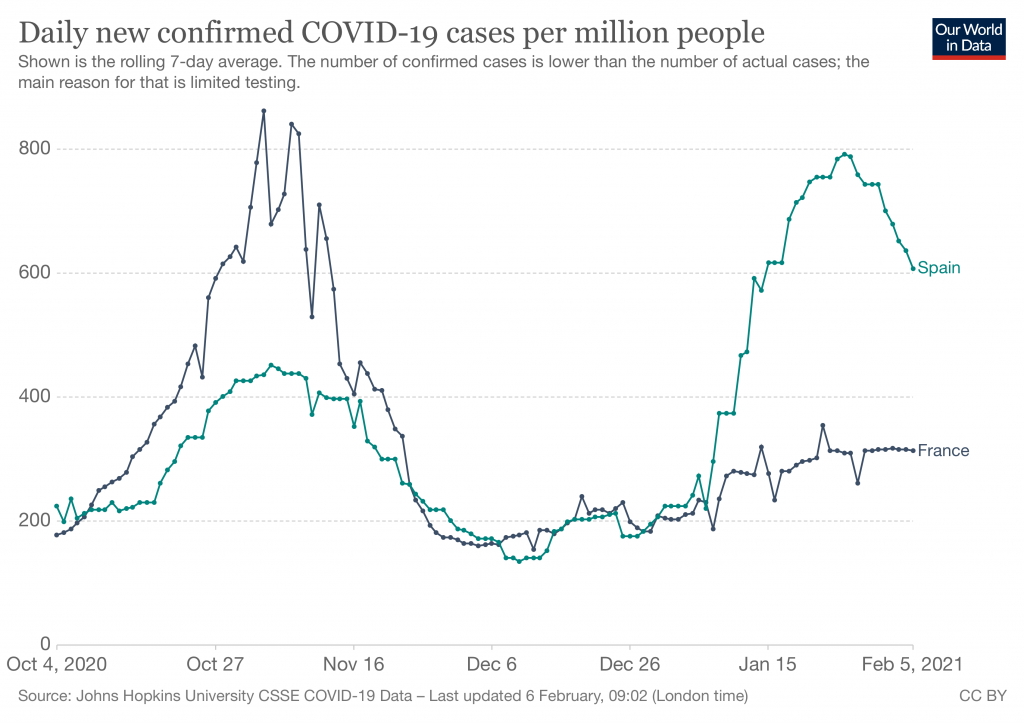

France and Spain haven’t imposed lockdowns this winter, yet cases have been declining in Spain since the beginning of February and they’ve plateaued in France.

Chris says in support of lockdowns that “the basic assumption that a communicable disease will spread exponentially unless action is taken should not be up for debate”. But it certainly is up for debate – and the above examples seem to show that cases don’t rise exponentially in the absence of lockdowns being imposed, but reach a peak and then begin to fall (or plateau).

A few minor points.

Chris was largely unimpressed by the 31 studies I linked to showing lockdowns are largely ineffective on the InProportion2 site. Try these 30 studies on the AIER blog instead.

Chris says it’s not true that lockdowns are historically unprecedented and cites the example of Philadelphia during the Spanish flu epidemic. But that city never issued a stay-at-home order. The closest any country came to ordering a lockdown before the Chinese Communist authorities imposed one in Wuhan last January was in Mexico in 2009, during the first days of the H1N1 outbreak. Those suspected of being infected were isolated, schools were closed, public gatherings were banned and a regional football tournament was cancelled. But those measures weren’t replicated in other countries in response to the swine flu pandemic and Mexico abandoned them after 18 days, partly due to the mounting social and economic costs.

Chris claims COVID-19 is “a highly infectious disease that kills around one per cent of those who contract it”. But he later goes on to say: “Around 20% of the population have had the virus, of whom over 100,000 have died. If 40% got it, 200,000 would be dead. If 60% got it, 300,000 would be dead. And so on.” But 20% of 67 million is 13,400,000 and 100,000 is around 0.75% of 13,400,000. So that’s an IFR of 0.75%, not 1%. And that’s higher than it should be because the one place our public authorities have “let it rip” is in care homes. A recent WHO bulletin estimates the global IFR at 0.23%. That’s less than one in four hundred.

Finally, Chris acknowledges that the Government didn’t carry out a cost-benefit analysis before placing us all under virtual house arrest on March 24th of last year, but he’s confident that one would show that the lockdown prevented more harm than it caused:

Given that the average person who dies from COVID-19 loses, on average, 10 years of life, and that much of the economic damage is caused by people’s response to the virus rather than the lockdown, any realistic estimate of how many deaths have been prevented – combined with the standard valuation of a quality-adjusted life year – would, I am sure, show that this lockdown has been worthwhile.

In fact, precisely such a “realistic estimate” has been done – by a group of economists at Imperial College, no less. In assessing the costs and benefits of the March – June UK lockdown, they estimate that the net cost, as measured in QALYs, ranges from £68 billion to £544 billion. Even on the most generous reading of the pro-lockdown case, whereby they allow that the lockdown saved 440,000 lives and only caused the economy to contract by 9% in Q2, with the other 11% attributable to the pandemic, the net cost was still £68 billion. Incidentally, they dispute the “10 years of life” claim: “The average figure of 10.1 years of life lost does not account for the fact that those who have died with COVID-19 have often been in poor health, conditional on their age.”

I enjoy debating with Chris, but he needs to stop tilting at straw men and get to grips with the strongest arguments on our side. When he replies to this, as I’m sure he will, I hope he addresses the Swedish data. It has experienced fewer Covid deaths per million than Britain in spite of never imposing a lockdown. The UK has done what the lockdown advocates wanted – not once, but three times. And yet it has the third highest Covid death toll per capita in the world.

Explain that, Chris.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostLatest News