by Julian D. Harris PhD

A great deal of pressure has been placed on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the assay used to determine the prevalence of COVID-19 cases. The UK government have invested heavily in several Lighthouse labs for COVID-19 testing, but there have been a growing number of concerns about the reliability of these tests. There’s a concern that the PCR assay may be inflating the number of COVID-19 cases by generating false positives.

What Causes False Positives in COVID-19 Testing

The PCR is an extremely sensitive and specific assay that inevitably generates a certain proportion of false positives. Apart from the well-documented false positive rate – whereby ~0.8% of people tested will be falsely designated as positive, even when the test is run perfectly – there are also false positives generated by the test’s over-sensitivity, whereby if you’ve had COVID-19, or another coronavirus, but are no longer infectious, you may still be shedding small components of the virus and test positive. That risk increases as the number of amplification cycles increases.

But there is a third cause of false positives which is when cross-contamination takes place between the samples being tested, so a positive sample can contaminate a negative one, turning them both positive. That’s the risk I want to flag up in this article.

My Time as a COVID-19 Responder Volunteer and Undercover Investigator for the Health & Safety Executive

I’m an experienced virologist and have a specialist knowledge of molecular biology technologies and biosafety level 2/3 (BSL2/3) facilities. So I volunteered at the Lighthouse lab in Milton Keynes, one of the main testing laboratories in the UK. The recruitment process was surprisingly lax, with the recruiting agent only asking if I could do nights. On my first day at the lab – July 6th – there was an absence of induction for BSL2/3 facilities, handling biohazardous samples and health and safety regulations. That shocked me because these lapses could not only mean a risk of cross-contamination, but could endanger the safety of anyone working in the COVID-19 labs at the facility.

After working at the lab for three days and discovering various safety lapses, I contacted the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), telling them of my concerns. We decided I would continue working there to see what else I could discover, then passing on information about any health and safety breaches to an HSE inspector, who advised me how to operate and how to stay safe. HSE had never experienced this situation before where someone working undercover within an organisation would pass on health and safety breaches in real-time.

I’ll give you some examples of the kind of breaches I discovered.

There were >20 Class II Biosafety cabinets (BSCs) for the initial processing of the swab samples. The cabinets are designed to protect the sterility of the samples and protect the operator from any potential contagion in the samples. Unfortunately, overloading cabinets with swab sample bags and unnecessary equipment was a common occurrence. This put the operator at risk of exposure to aerosols containing pathogens escaping from the cabinets into the lab environment, as well as endangering the integrity of the swab samples in the cabinet and risking them becoming contaminated by virus and virus comnponents circulating in the lab.

A build-up of dirt in the cabinets can also compromise the integrity of the swab samples. But there was no schedule at appropriate intervals to fully clean all interior surfaces of the cabinets. Fumigation of the cabinets to inactivate any contaminants before servicing – which is supposed to happen regularly – only happened annually at this lab. The UK Biocentre, which operated the lab, felt it was acceptable to clean an unfumigated cabinet by sticking half your body into the apparatus in an attempt to clean the interior. Another high risk practice was technicians regularly doubling up to process the biohazardous swab samples, interrupting the protective air flows generated by the cabinets and further increasing the risk to the integrity of the cabinet environment.

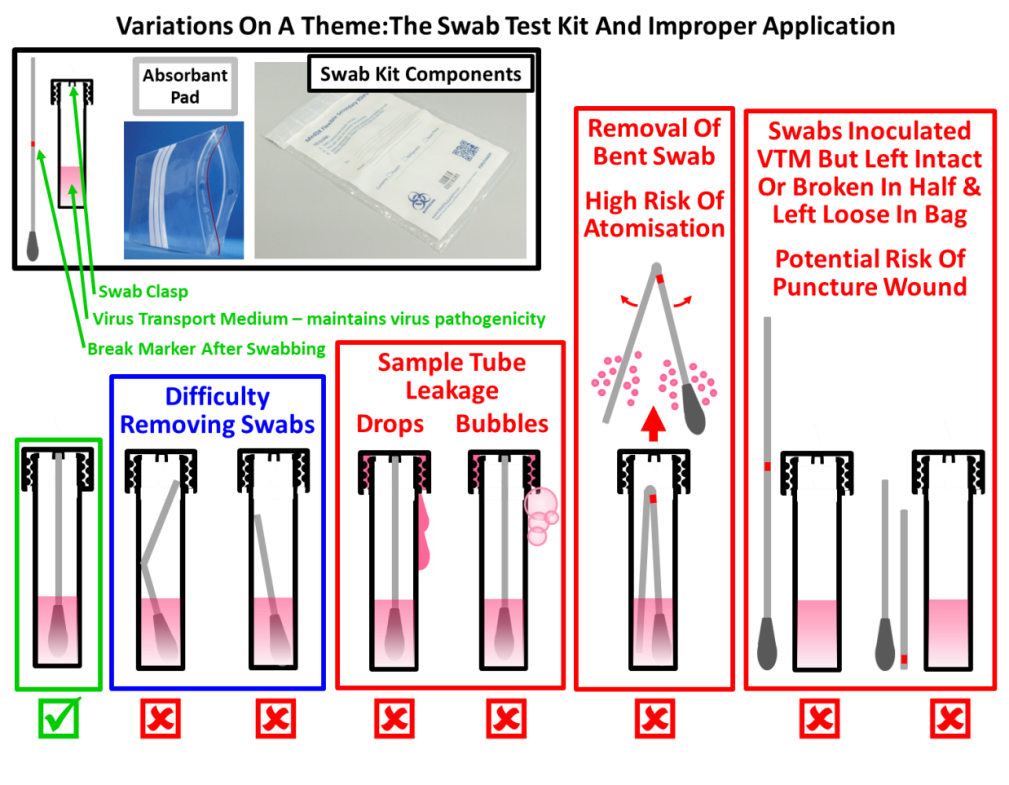

The lab where the real-time PCR assay was run was kept under positive pressure for processing purposes, which meant no air from other areas was supposed to enter this room and potentially contaminate the assay. But cross-contamination issues started at the beginning of the process before the samples were taken to the PCR lab. The main causes of cross-contamination are the way members of the public use the swab kits; contamination of the insides of the tubes and cap by the operator; and the contamination of the thread of sample tubes with sample medium as shown below. These issues are exacerbated by the poor quality of most sample tubes/caps and suppliers’ mix-and-matching tubes to caps, so some of them don’t fit properly.

A dangerous practice I observed in the lab was the passing of leaky tubes to the liquid handling personnel, unknowingly putting them at risk, as well as contributing to the risk of cross-contamination.

When I Came Out as Working with the HSE

When I started working at the lab, I approached several lab managers about some of my concerns, but after the fifth attempt I realised my issues were being ignored and I knew I was just becoming a nuisance. It’s then that I decided to contact the HSE. At the end of July, I told a UK Biocentre manager I was extremely upset and concerned about the dangerous practices I was observing. Later that day, HR suspended me from the workplace. At a meeting with managers for me to receive “feedback”, they not only validated all my health and safety concerns described in the report I had prepared ahead of the meeting, but offered me a promotion that included various health and safety responsibilities in the COVID-19 testing labs, including preparing PowerPoint presentations and practicals for new employees, as well as the existing COVID-19 personnel, on subjects that should have been part of the health and safety induction on my first day.

That was a positive step – or so I thought. But the UK Biocentre personnel became increasingly hostile, making it difficult for me to carry out my new duties. The situation came to a head on August 13th, when I told the training manager that I had been in contact with the HSE, and the following day I was suspended by HR. On August 18th, HR told me that I was now suspended pending the outcome of a disciplinary process and falsely accused me of assaulting a receptionist.

That evening I phoned the police, who told me that the assault could not have taken place because they hadn’t been informed and the reception area is saturated with CCTV. I contacted the HSE to tell them what had happened and it approached the UK Biocentre on August 24th. On August 25th I began working with the BBC and the Independent on a collaborative investigation to expose the dangerous working practices at the lab. On October 6th, the HSE informed me it had concluded its investigations, but neglected to send me the findings. After the BBC formally contacted the HSE, it released a statement saying it had identified five material breaches of health and safety legislation at the lab that included inadequate health and safety training for staff, and employees working too closely together.

On October 15th the BBC and the Independent simultaneously broadcast and published a story about this, but the HSE would not release its detailed findings to them which meant the journalists were only able to describe the breaches in broad terms. I subsequently submitted an FOI request to the HSE and yesterday it released the letters it sent to the UK Biocentre about the specific contraventions of health and safety laws it had identified during its investigation. You can read those letters here.

Concluding Remarks

There are many unknowns in the “black box” in the Lighthouse labs, whereby swab samples enter at one end and a COVID-19 test result comes out at the other. At the induction I attended, I and the other new employees were told to keep quiet what goes on within these walls.

Independent scientific evaluation of the Lighthouse labs is impossible due to a lack of transparency. When I requested information that could have helped me assess the reliability of the test results – the nature of the primers being used in the test, for instance – I was told this was proprietary information as the test ingredients are manufactured by a private company. It is of significant public interest to have access to this material, as it would tell us whether the COVID-19 testing at these labs is fit for purpose. In particular, it would help us determine to what degree the labs are inflating the proportion of the population that have a COVID-19 infection.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostUnlock Manifesto