Abstract

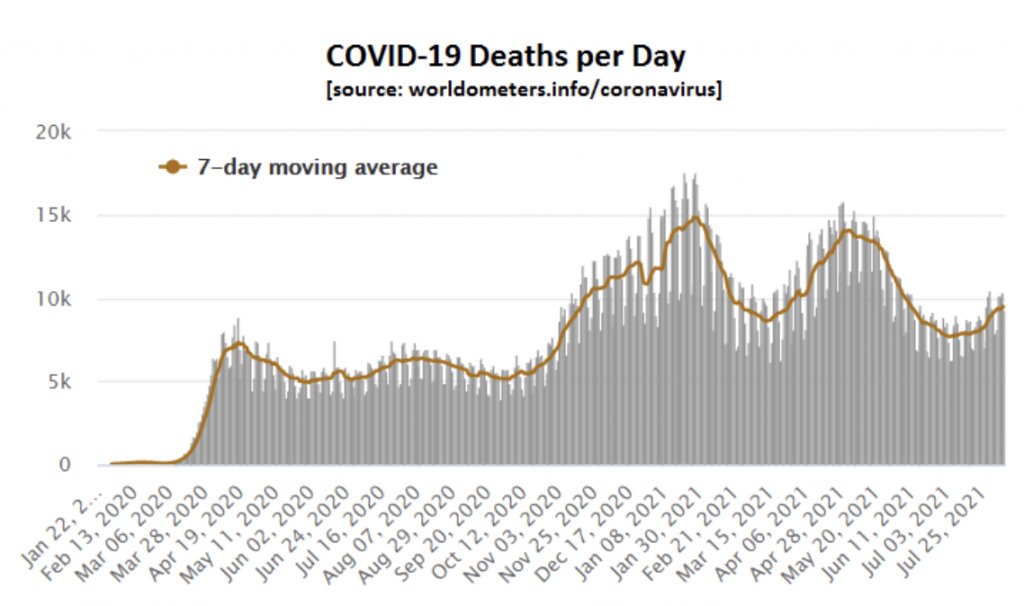

- A series of SARS-CoV-2 variants have arisen, many of which possessed a transient selective advantage that led to a wave of infection that peaked some three-to-four months later. Several such variants have spread globally, though different successful variants have arisen simultaneously in a number of countries. The result is a three-to-four month wave pattern per country, which is also apparent globally.

- Seasonality affects variant transmissibility. Colder seasons accelerate the growth and increase the size of waves, but the continually changing environment may also differentially affect the relative transmissibility of competing variants (i.e., negatively as well as positively), thereby helping to terminate previously dominant variants and promote the growth of new ones.

- Overall there is a minimal positive impact from quarantine policy, isolation requirements, Test and Trace regimes, social distancing, masking or other non-pharmaceutical interventions. Initially, these were the only tools in the tool-box of interventionist politicians and scientists. At best they slightly delayed the inevitable, but they also caused considerable collateral harms.

- Immunity created by SARS-CoV-2 infection, layered on top of pre-existing immunity due to cross-immunity to other coronaviruses, provides good protection against infection, severe disease/death, and being infectious. Immunity created by vaccination also helps protect against serious disease and death, but does little or nothing to provide protection against infection or being infectious (which completely negates the case for vaccine ID cards).

- Population immunity stems mainly from natural infections, with vaccines adding only slightly to this (and only in recent months). Population immunity is created by societal waves of infection and is somewhat variant-specific. An emerging new variant is able to infect (or re-infect) some fraction of individuals and this serves to top up and broaden the scope of our population immunity to also protect against the new variant.

- This empirical and data-driven understanding of the pandemic allows us to make predictions. Such predictions don’t look good for some of the U.K.’s new Green List countries. But in these and all other places the ongoing arms-race between viral mutations and growing human immunity will always eventually be won by the human immune system. The virus then becomes a low-level endemic pathogen in equilibrium with its human host species. If this were not the case all humans would have been wiped out by viruses eons ago!

For the past one and a half years, experts and amateurs alike have been trying to understand the Covid pandemic, hoping to be able to defend against it and predict how it will develop and end. A multitude of uncertainties has led to an environment of fear, and regrettably, that fear has been exaggerated and employed to justify policies that may or may not have been effective but were uncomfortably authoritarian. Perhaps it had to be this way, given that no one had a working crystal ball (not least the computer modellers) and yet people at all levels needed to feel they had some degree of control over the situation. The sad truth, however, is that our leaders, scientists and the public have basically been stumbling through the Covid quagmire, challenged by complexities of subjective data interpretation, imperfect modelling, political machinations, hidden agendas and unhelpful human egos.

Here, I attempt to pull together an empirical and rational summary of the underlying driving forces behind the whole pandemic. This is aided by the fact that modern genetic technologies have enabled extensive virus testing and variant detection, while vaccines and lockdowns have been applied to very different degrees in different countries thereby giving us many alternatives scenarios and empirical observations for direct comparison. From this, it becomes increasingly clear which factors did and did not truly drive the dynamics of the pandemic.

A central conclusion has to be that despite all our efforts, this SARS-Cov-2 virus has done what it was always determined to do. It spread across populations via waves of infection, and like ripples of water from a dropped stone these waves have been remarkably evenly spaced (by three-to-four months). This repeating pattern of rises and falls in virus prevalence has remained sufficiently synchronised across the planet to be apparent in the global death chart.

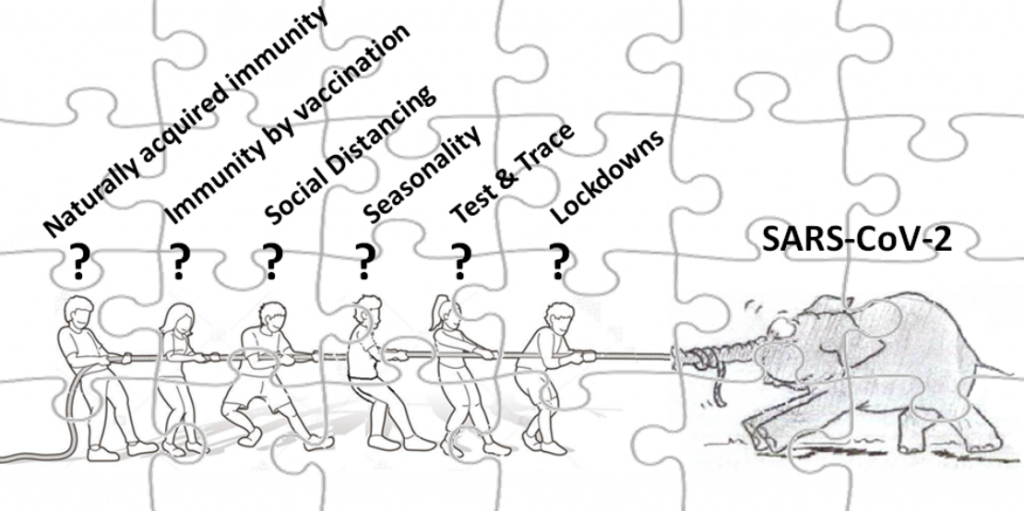

To make sense of this picture we need to consider the box of jigsaw pieces from which it can be constructed – that is, the range of factors that are driving (alone or in combination) the ability of the virus to spread well for a while before then losing that ability (operationally even if not innately), with uncanny regularity.

First up has to be the ‘virus variant’ piece of the puzzle. Time and time again we have seen new variants emerge which progressively displaced the previously dominant variant(s). As soon the ‘Wuhan’ variant began spreading around the globe, the forces of mutation and natural selection created an array of more transmissible strains that quickly supplanted the original strain. Many countries saw numerous variants competing with each other to achieve dominance, and several of these variants spread between countries. But within less than six months this initial ‘battle of the variants’ settled down to a far smaller number of the most transmissible variants which started to spread and dominate worldwide. Obvious examples include the Spanish variant (20A.EU1) of last summer/autumn, followed and displaced in many places by the U.K. variant (Alpha) just three-to-four months later over the autumn/winter/spring. And now three-to-four months after that, the Indian variant (Delta) has been establishing itself as the major variant almost everywhere. It is thus apparent that waves are being driven by variants that have some selective advantage(s), but critically we need to understand what the mechanism is that creates this advantage.

One big clue comes from the fact that each variant wave, regardless of location, continues to respect the noted three-to-four-month time period. Theoretically, replacement sweeps could entail variants that possess no or very little transmissibility advantage over other/previous variants. However, given the way some variants have been seen to spread between countries and then replace whatever previously dominant variant(s) existed in those other places, we can conclude that increased variant transmissibility is a large puzzle piece in the overall Covid picture. But saying that some variants have a significant transmission advantage at certain time periods and settings does not mean that this advantage is an inherent or a permanent property of that variant. This is because transmissibility depends on many other pieces of the puzzle.

One such additional puzzle piece is seasonality. Seasons change significantly over the timeframe of a few months, which is compatible with the rate of change for Covid waves. This makes seasonality a good candidate as a second large section of the Covid picture. Seasonality is widely accepted to have helped truncate the first U.K. wave in spring 2020, as the weather warmed up from mid-March. It is also notable that variants that arrive in a country during winter lead to new wave peaks in a far shorter time frame than they do in summer. But variant-driven waves occur in all the seasons, including in warmer periods (e.g. the Delta variant arose in India and spread to many other summer localities). So the seasonality puzzle piece might partly work by differentially changing the effective transmissibility of each variant. Specifically, as the seasons change, an initially dominant variant might find itself no longer especially compatible with the altered environmental conditions (and/or the associated changes in human behaviours). Conversely, one of the myriad background variants being repeatedly re-created by random mutation (or recently imported) might instead now be most suited to the new seasonal conditions. This new variant would then inevitably embark on a rapid replacement sweep. This rather obvious model of how evolutionary selection must work in a changing environment also fits perfectly with the observation that the secondary attack rate (SAR) of a new variant is initially higher (~15% according to PHE) but then reduces over a few months (<10%), even though the genome sequence of that variant is constant.

Several additional factors could contribute to making a dominant, highly transmissible variant less transmissible and less prevalent. Lockdown supporters would undoubtedly rummage through the box of Covid jigsaw pieces for anything having the appearance of a quarantine policy, an isolation requirement, a Test and Trace regime, a masked face, or some social distancing behaviour. Objective evidence indicates that such Non-Pharmaceutical Intervention (NPI) measures may together have had a marginal net effect on the rate of viral transmission, but overall they completely failed to halt the progress of the pandemic (see here, here and here). Instead, by slightly reducing the ease with which infections occur, they simply slowed the average rate at which people became infected (e.g. even a 50% reduced exposure would mean it simply takes four instead of two visits to a crowded environment to become infected). We know they did something because the incidence of all other respiratory viruses has reduced dramatically over the course of the pandemic wherever such measures were applied (even in Australia, where Covid is all but absent). Most respiratory viruses have Ro values of less than two, and so suppression measures need only be mildly potent to push these Rt values below one. In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 has a far greater Ro (typically estimated as three-to-four, or even more) and so those same suppression measures will not so easily push the covid virus Rt below one. Furthermore, people instinctively act more defensively when they know the virus is spreading rapidly, and so there may be very little added benefit of lockdown-related measures over just letting people respond naturally. This would then explain why there is no obvious impact of lockdowns in any curves of virus prevalence over time, why studies are yet to convincingly demonstrate any significant beneficial effect of lockdowns or masking, why virus prevalence began falling in the U.K. before the November 2020 and before the January 2021 lockdowns, and why we witnessed nothing whatsoever of the pessimistically-predicted massive ‘Exit Wave’ after the U.K.’s ‘Freedom Day’ on July 19th, 2021. So perhaps we allow NPI jigsaw pieces to have a token role as supporting edge pieces in the jigsaw, so long as we never overlook the enormous collateral damage they also impose (past, present and future).

That leaves just one final type of jigsaw piece – population immunity. Building on pre-existing cross-immunity to other coronaviruses, immunity due to SARS-CoV-2 infection is superior to immunity generated by vaccination in that it defends against a broader range of variants and engenders good protection against infection, illness and infectiousness. By contrast, vaccines do little to stop a vaccinated individual from becoming infected or being infectious (see here and here) and whatever small benefit they may provide in terms of reducing transmissibility will merely delay the occurrence of infections, as explained above for NPIs. Vaccines are, thankfully, very good at reducing serious illness, hospitalisation and death, and so on that basis they are only well merited for use in old and vulnerable individuals. It is critical that the very significant limitations of vaccines regarding infection and transmission control are now widely advertised and understood, as this makes the idea of vaccine ID cards completely nonsensical in scientific terms – as well as highly discriminatory and illiberal. Vaccine safety profiles are an additional consideration.

Nevertheless, to some degree, the combined effect of vaccines and natural infection generates our overall level of population immunity, and this must be playing some role in terminating each variant wave every three-to-four months. Substantial population immunity in the U.K. was achieved by the initial Covid waves of spring 2020, as evidenced by its impact on the development of second waves later that year. The peaking of each Covid wave in all places has little or nothing to do with lockdown measures (as explained above). It also cannot have much to do with immunity generated purely by vaccination, given that the vaccinated individuals still catch and pass on the virus, and that many waves ended in 2020 before vaccination campaigns got underway. This leaves only population immunity as an explanation, working in concert with the seasonality effects described above.

To fully understand the role of herd immunity in wave termination, one must recognise that while the level of population immunity achieved at any stage may be sufficient to suppress the spread of a dominant variant (whose SAR may also be falling due to seasonality effects), it may not be sufficient to restrain the next emerging variant (whose SAR would be temporarily high owing to partial immune evasion or seasonal advantage). The new variant may also arise and spread in somewhat different sub-sections of society (age, ethnicity, geography, etc.) than did the previously dominant variant. Thus, herd immunity would be expected to have to be topped up and broadened by a wave of further infections and re-infections in society, in order to bring each subsequent wave to an end. This seems to be what is happening, with each sequential wave being generally smaller and ending naturally despite fewer suppression measures being enforced as populations tire of having their lives and freedoms excessively restricted. This also fits with the fact that over 95% of U.K. adults and 80% of 16-24 year-olds now have detectable Covid antibodies, much of which comes from natural infection. Others will be immune without detectable levels of antibodies, and from prior infections and cross-coronavirus immunity.

So overall we can be pretty sure that population immunity is now contributing to (and possibly directly causing) the ending of each wave of Covid infections. It certainly has lowered the Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) down to or below that of influenza for society as a whole, meaning that the vaccination of the young cannot now be medically or ethically justified (especially given the substantial known and unknown risks imposed by these novel genetic technology vaccines). A scientific consensus on herd immunity will presumably begin to emerge, as the data and jigsaw pieces all continue to fall into place. Indeed, even lockdown champion Professor Neil Ferguson recently confirmed that because we have now released all lockdown measures in the U.K., this latest wave “will peak because herd immunity has been reached”. And it has indeed now peaked!

Finally, with an essentially complete Covid jigsaw picture now assembled using an empirical data-driven approach, we can offer up some testable predictions. The first is that current Delta waves unfolding in different countries will reach natural peaks around three-to-four months after this variant arrived in each location. For example, considering countries recently added to the U.K.’s Green List, we would expect: Slovenia, Slovakia and Romania (where Delta arrived little more than one month ago) will see their nascent summer waves grow further and peak in about two months’ time; Latvia (where Delta has only just arrived) will face a multi-month wave starting very soon; and Austria, Germany and Norway (where Delta has already been present for several months) will likely see their summer waves peak around the end of August. NPIs will do little to change this, and neither will vaccines (see Israel for evidence of this).

The really big question, however, is whether or not Delta is the last major variant we will all have to deal with. SARS-CoV-2 and the human immune system are basically in an arms race. Population immunity increases and targets the latest variant, causing new variants with different immunological profiles and transmission advantages to rise in abundance, which in turn further strengthens and broadens our population immunity. Vaccines merely help accelerate this arms race. But the end of the war is always the same – the virus runs out of strategies a long time before the highly adaptable immune system runs out of defences. The virus then gives up and resigns itself to becoming a low-level endemic pathogen in equilibrium with its human host species. If this were not the case all humans would have been wiped out by viruses eons ago! What we do not know is whether Delta is that last throw of the dice for Covid, or whether one or a few more guises of troublesome variants will yet come along. If they do, from what we now know we should probably place more trust in our immune system than we have in previous waves. And in either case, we can be very sure we are far closer to a permanent and natural end of this pandemic than we are to its beginning.

Anthony Brookes is a Professor of Genomics and Health Data Science at the University of Leicester.