Nature published a comprehensive study this week on cardiovascular risk including a total of over 11 million patients that has made a few headlines. The aim was to identify the cause of increased cardiac pathology. It should have been a very simple study comparing four groups:

- Not infected and never vaccinated

- Not infected and vaccinated

- Infected but not vaccinated

- Infected and vaccinated

It is hard to believe the authors did not look at these groups, but whatever was found when comparing them remains a mystery.

Instead, the following groups were compared:

- Not infected and never vaccinated data from 2017

- Not infected, including vaccinated and not vaccinated

- Infected but not vaccinated

- Infected with vaccinated people included but using modelled adjustments

When studies with huge datasets use modelling and fail to share data prior to their adjustments alarm bells should start ringing. Therefore, I took a deeper dive to see what else was questionable.

There were serious biases in the paper which need addressing but first let’s look at the critical question of myocarditis (heart inflammation).

Because of the known risk of myocarditis from vaccination it is worth looking particularly closely at the data presented on this. Oddly, for the issue of the day, the data on myocarditis was all hidden in the supplementary appendix to the paper.

The risk of myocarditis appears to be an autoimmune (the immune system attacking the heart after interaction with the spike protein) rather than direct damage by the virus/vaccine spike protein. Therefore, myocarditis could result from the virus or the vaccine. The key question that needs answering is whether vaccination protects or enhances the risk from the virus.

The authors report 370 per million risk of myocarditis after Covid infection in the unvaccinated. The contemporary control rate was 70 per million and the historic one was 40 per million. What was wrong with the contemporary controls?

They made it clear they removed those who had been vaccinated from the calculation in the Covid arm but they did not state they did this for the control arm. Did vaccination lead to a 30 per million increase in myocarditis in the control arm? Given the cohort appears to be old and we know myocarditis incidence is worse in the young a one in 30,000 incidence is significant.

What about those who were vaccinated and had Covid? Once vaccination (and modelling) were included, the rate rose to 500 per million. It is not entirely clear whether supplementary Table 22 excludes those who were not vaccinated, but given that it does not state the unvaccinated were excluded from this data it is fair to assume the 500 per million relates to the whole population.

Given the higher risk of myocarditis after vaccination one might wonder whether this study showed protection from infection due to vaccination, as this would lower risk from the virus. Hidden in the legends of the supplementary tables the authors reveal that 62% of the Covid patients had been vaccinated compared to 56% of the non-infected controls (not a great advert for vaccine effectiveness against infection).

Using the fact that 62% of the Covid cohort were vaccinated and that the unvaccinated had a rate of 370 per million, to get to an overall rate of 500 per million the vaccinated 62% must have had a rate of 580 per million (580×0.62 + 370×0.38 = 500). Therefore, in those with Covid and vaccination the rate (even after modelling) was 210 per million higher (58% higher) than the unvaccinated with Covid. (If supplementary Table 22 did exclude the unvaccinated the incidence of myocarditis after Covid would have been 35% higher in the vaccinated.) An extra 210 per million works out as an additional risk from vaccination of one in 5,000 among a relatively old population. The 35-58% higher myocarditis rates seen in the vaccinated after Covid compared to the unvaccinated was based only on diagnoses made more than 30 days after their positive Covid test. Any rise in risk in the first 30 day period was censored from the study. How high was it in the first 30 days and for the younger men? This critical question was left unanswered.

The data comprised medical records for U.S. veterans who were 90% male, three quarters white and had a mean age of 63 years.

Two control groups were selected:

- Patients who had used healthcare in 2017 and were still alive in March 2018.

- Patients who had used healthcare in 2019 and were still alive in March 2020.

These groups were compared to patients who tested positive for Covid after March 2020, with each patient being matched to one patient from each control and measuring beginning from the same day as the positive test but two years earlier for the 2018 control.

There was a significant bias between these two control groups and those who tested positive.

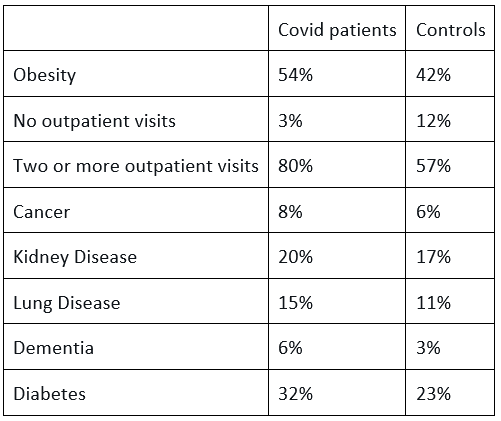

The Covid patients (not just those who were sick with it – all those who tested positive) were more obese, saw doctors more often, had more cancer, kidney disease, lung disease, dementia etc.

There are two ways to deal with such biases. One is to match the 150,000 Covid patients with similarly sick patients from the over five millions controls. This reduces the size of the control group but when it is already so large this should not be a concern. Instead, the authors modelled the data until the groups seemed similar. Using an algorithm they claimed the same total number of people were present in the Covid cohort, but whereas 49,407 actually had diabetes in the raw data, 11,903 (24%) no longer had diabetes according to the weighted data. Similarly, 14% were ‘cured’ of lung disease, 14% of cancer and a full 35% of the dementia patients no longer had dementia.

There was no discussion in the paper about the reasons for this unhealthy bias among the Covid patients. All positive test results were included and anyone can catch SARS-CoV-2, so the factors that increase the risk of serious disease and hospitalisation should not have biased a dataset based only on infection. Instead the authors discuss the hypothetical issue of people in the non-infected control group having Covid but not getting tested such that the damage caused by Covid could be worse than the paper reports.

It has been well established that hospital transmission dominates as a source of spread and SAGE has reported that up to 40.5% of cases could be traced back to hospital spread and a majority of hospitalised patients in June 2020 were linked to hospital spread. In Scotland, in December 2020, 60% of the acutely ill with Covid acquired the infection in hospital. Patients accessing hospital are highly likely to be less healthy than the general population. Indeed, we know that the Covid patients in the study accessed hospital more frequently than the controls. If the bias was related to hospital acquired infection then the whole study is called into question, as people who attend hospitals are more likely to be sick.

The authors picked some control conditions to attempt to show they had not introduced a bias. Given the study was about cardiovascular diseases, including those that are an immediate threat to life and those that are very common, I would have picked conditions that might kill you within a year, like lung, pancreatic or oesophageal cancer and common conditions e.g. urinary tract infections, diabetes or prostate cancer.

The authors chose three rare malignancies, all with a one-year survival rate of over 80%, and pre-invasive melanoma – why not include invasive melanoma? They then included rare conditions and odd selection of: hypertrichosis (‘werewolf syndrome’ with excessive facial hair), sickle cell trait and perforated ear drums. When the choices are so niche it begs the question of what the results would have been if more obvious choices had been selected.

The group that tested positive for Covid did badly: 13% ended up in (or began in) hospital and 4% in ICU. The mean age was 63 years which may explain part of the high percentage of sick Covid patients, but it does, again, suggest this group may have been more vulnerable than the control.

They then compared the risk of various cardiac outcomes against the controls. However, they used the same control to compare non-hospitalised patients as patients who had received ICU care. Of course, people who have needed ICU care will be more likely to have cardiovascular complications. Indeed, many of the patients may still have been in the ICU when the measuring period began 30 days after the positive test. A fair study would have only compared the ICU outcomes with the sickest people within the control group, not the average of the whole control group.

The risk to the non-hospitalised Covid patients was low for almost all the cardiovascular risk factors.

The risk to the hospitalised was higher (but remember the controls had significant biases).

Those on ICU had a much higher risk. What is not clear is how much of this is because of the virus.

It is not a surprise for people who have had an ICU stay to be unwell for some time afterwards. The risk of ICU admission for Covid was higher than for influenza, but it is important to understand how much of the cardiovascular risk resulted from the virus and how much from the stay in intensive care per se. How do these Covid ICU patients compare to other ICU patients? The paper did not say.

Similarly the paper makes no attempt to unpick how many of the Covid patients tested positive only after being admitted to hospital. If, as in other studies, a significant proportion acquired Covid in hospital, then a higher risk of being diagnosed with other conditions would be highly likely.

Having failed to examine the above two questions – how much cardiovascular disease was a confounder of hospital transmission and how much is secondary to ICU harm – the overall risk of consequent cardiovascular problems included all the above cardiovascular conditions and thereby inflated the average for the Covid population as a whole.

Nature has published this paper which presents data in an obtuse way that should never have passed peer review. The results were presented as showing how dangerous the Covid virus was for cardiovascular complications without suitable controls to enable that conclusion to be drawn. The evidence on vaccination risks was hidden and not presented in a meaningful way for different age groups. Even then, they demonstrated a significant risk of myocarditis after vaccination, particularly after then encountering the virus but this key finding was hidden in the supplementary appendix. Why?

Dr. Clare Craig is a Diagnostic Pathologist and Co-Chair of HART.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“especially when compared to Sweden”….They still engaged in state democide, and that gave the Lockdown fanatics ammunition to say, they had higher deaths than before!

“He and his ilk have gone very quiet now that there are, indeed, thousands of unnecessary deaths. Among people, many of them distressingly young, who had early cancer symptoms”…..Aye and also heart related issues but even Allison will not go there!

Well I’m on the fence if there even ever was a ‘Covid 19’ virus. We know there wasn’t a pandemic, we’ve got all the data we need to prove that, but was there a lab-made virus? There were certainly incentives to creating the illusion of one and we know that people stood to gain from the world falling for this hugely elaborate con, therefore no wonder those in authority lied to us and committed fraud from start to finish. We’ve masses of evidence of this by now. And I’m sure this is the longest we’ve gone without them wheeling out another ‘scariant’.

But if ‘Covid’ was just the flu repackaged all along, why have we never ever heard of them treating flu previously with safe and cheap drugs such as Ivermectin and Hydroxychloroquine? They were shown to be effective against ‘Covid’ if given early, after all. So many people in the so-called ‘Freedom Movement’ are still referring to the epic con as a damn ‘pandemic’ though. Surely they should know better by now. These are intelligent people who are experts in their fields. Here’s Mike Yeadon calling out Tess Lawrie for constantly referring to ‘Covid 19’ and early treatment, because he’s adamant it doesn’t exist. By referring to a ‘pandemic’ experts are basically giving legitimacy to what was the biggest and most harmful con of all time, in my view, which plays into the hands of the culprits, which then makes it easier for the likes of Bill Gates et al to keep hinting at ”the next pandemic”, like it’s a bloody bus that’s due!

”Tess knows perfectly well by now that there was no pandemic. No new illness called Covid19.

So I ask her publicly to state why she continues to promote “early treatment” for a non-existent illness.

Now, it’s entirely possible that any agent, used off-label, has some utility. A great many prescription medications have some utility in illnesses that were not the initial illness for which they were developed. I’m not disputing that.

However, I am very troubled by anyone pushing the line that “regulators sought to block the use of lifesaving medications during the covid pandemic”, because there was no pandemic.

I wish I didn’t think this, but I can find no other motive for pushing this line, except to amplify the campaign of fear that the perpetrators intend you to feel, in relation to “future pandemics”.

There aren’t going to be future pandemics. They are a lie. They are a hobgoblin designed to frighten you into allowing the authorities to steal what’s left of your freedoms and all of your medical autonomy.

Tess, please stop doing this.”

https://interestofjustice.substack.com/p/dr-yeadon-asks-dr-tess-lawrie-to

Personally I don’t like to use the word pandemic, and I don’t like articles that use that term. I refer to Lockdowns, plandemic, Covid psyop or pseudo pandemic. Regardless of if it was a new virus, there was no pandemic by the old definition so by calling it a pandemic people are taking part in this implicit manipulation.

Scamdemic is my default.

mine too, it feathered the nests of lots and lots of politicians, academics, clinicians,Pharma, Billionaires, advisors, and of course members of the WEF,UN,and WHO. Organised crime members.

And ‘Quacksines’.

It is mass delusion or psychosis.

Pandemic started life as an adjective meaning “affecting the whole of the population” whereas epidemic means “nearly the whole population”, and was originally qualifed by the thing it described eg pandemic influenza, pandemic delusion but is never absolutely accurate because a lot of us weren.t affected.

Whatever I had in December ’19 was the worst ‘whatever’ I have ever had. I am an asthmatic and have had Influenza ‘A’ five times in my life, I have had pneumonia once and in none of those have I ever been so ill. It ended with me in hospital on oxygen and the Doctor admitting that it was not flu but a bit of a mystery virus. They had seen several people with it. For most it was just a bad cough which felt as though your underpants, or toenails, were coming up; and that was it. For a few, it was very bad.

I had a nasty cold in December 2019 with a strange dry cough, went to Dr because I developed ear ache which the Dr gave my antibiotics that didn’t seem to help. I only lost a few Gym days as I recall. That is how I measure an illness….It is down to how long it keeps me from the old pump!

Mark Harper has just approvingly highlighted “the prime minister’s role in “finding the money to pay for rolling the vaccine out when [Harper] was chancellor”. Apparently there was a “vaccine bounce” in support for the Conservatives in an earlier election as a result. The trouble with bouncing weapons its that they go down as well as up. Weaponising ozone, climate and viruses and other natural phenomena is invariably politically disastrous in the long term, even if it garners a few votes at the time it is launched. All the parties would be safer sticking to adjusting human-created phenomena, such economics, law and migration.

Yes I heard that “vaccine bounce” on the radio, they need to talk with Andrew Bridgen more instead for running out of the chamber whenever he discusses excess deaths.

“The simple step of a courageous individual is not to take part in the lie.” A. Solzhenitzyn.

For anyone who can still stomach any more Covid-related stuff this new documentary looks good but I haven’t watched it. Epidemic of Fraud came recommended by The Midwestern Doctor ( 2hrs );

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CmvwyuV7Uvk&ab_channel=EpidemicofFraudOfficialChannel

8 o’clock on Thursday and the muppets over road are still clapping for carers!

Some people are a lost cause and it’s best to just let them get on with it because they can prove quite the energy vampires. Best to just leave well alone because, given the amount of time that’s elapsed, they would have woken up by now if they were ever going to. Mind, we can say the same for any of the BS narratives that ‘Kool-Aid and the Gang’ are dutifully swallowing whole. Sucks to be them.

However, there’s nowt to say you can’t still laugh at them though. Hell, I would!

Point and laugh!

are you serious? maybe they are just an alternative band having a practice, or just mental.

You’re never serious?

A very lonely time, indeed.

Well, I have found a huge circle of new friends. Those who think. Those who will be free.

It truly is an ill wind if it blows no good…

Not sure about Hutchins, but Pearson never whispered a dickie bird about the ‘vaccines’ during the time it mattered. As for JHB, she couldn’t get enough of the stuff from what I remember. As I’ve said before, if Pearson was kept quiet by the powers that be, then now’s the time to come clean. If, however, she’s just run along with the rest, then she’s got nothing to be proud about. The only one mentioned that did actually openly criticise the whole Covid shit show was Toby Young… who now seems to only say anything that’s within the overton window.

I respect her and Liam immensely for standing strong against lockdown nonsense. Planet Normal is a worthwhile podcast.

I will take my allies where I find them. Allison is a good reporter and Liam’s a credible economist. Play to your strengths.

While I know the jibbyjabbies were shite and the whole political edifice was thoroughly corrupt, due to my ‘credentials’ I’d get nowhere arguing this in the public forums. I’d much rather they bang the drums they’re most qualified to bang.

An army’s not all artillery. You need signals, engineers, infantry and tanks. I’m very happy to have them on our side on much of this subject, and they’re primed to go to bat for a particularly egregious revelation on the topic of the jabs.

Who here is able to say they were right about absolutely everything? My instincts told me the response was just plain wrong. I was wrong on a few things but still mostly correct.

For me, my resistance to jabbination was the stubbornness arising from ‘lockdown is evil, the rules are contrived, masks are dogshit, the data is adulterated and seriously misrepresented by the media. Who the fuck do the govt think they are ordering me about like this?’

The research on the jabbies came afterwards.

Totally agree GHD. It is very disappointing to me that many on our side are far too quick to criticise people who aren’t as far down the rabbit hole as us. It really is something when people think Toby Young is “controlled opposition”. The fact is that people with high profiles like Toby and Alison Pearson can not – must not – travel too far away from the Overton Window. They have to remain credible in the eyes of the establishment at all times if they are going to be effective at shifting the debate our way.

I’d go so far as to say that calling someone out as “controlled opposition” is a type of sceptic virtue signalling.

Plus it is very depressing and strips us of all agency if Toby, Alison Pearson, Julia H-B, Andrew Bridgen, etc etc are all working for the other side. Personally, I think James Delingpole with his “if you’ve heard of them, they are a wrong-un” mantra is the most likely to be controlled opposition with his depressive diet of doom and gloom and nothing-can-be-done-except-pray advice. What could the establishment want more than a depressed opposition advocating doing nothing?

Actually I found Dellingpole refreshing that one (or two) times he was on GB News. He points out some home truths that only Neil Oliver talks about on his (possibly deliberate) broken up Sunday show.

That is what puts me off GBN because they talk about the Tories/Labour like they’re any different. They are part of the same Globalist Uni-party that is dragging us to hell in a handcart. Only difference is the colour of the rosette.

“The fact is that people with high profiles like Toby and Allison Pearson can not – must not – travel too far away from the Overton Window.”

I disagree. You go where the truth takes you. If you know the truth but lie (by omission, in Allison’s case), I think that is unacceptable and a betrayal of the public and their followers.

Your counterargument (I assume) is that journalists exposing a truth that lies beyond the Overton Window (think covid vaccines, Jan 6, 2020 Election Fraud, climate) risk loss of their job or being cancelled from public forums (like the BBC’s Question Time).

My response? People will literally have taken the vaccines because they believed Allison Pearson supported them.

Hi Michael – a couple of points. The “truth” at the edge of the political debate is very much up for grabs especially in an era where we are all in our own echo chambers, so some nuance and discussion is fair enough. Secondly, even where something is “the truth” eg trans women are not women, political commentators have to be careful how they phrase stuff because the left will always be waiting to trip you up. So no one in the world believes trans women are actual women, but some (maybe many) think they should be treated as actual women. The left, who are so much better than us with words shorten this to trans women are women knowing this will produce outrage and controversy and allow them to cancel people all over the place. This only works of course when they have the power, which it seems they do.

My resistance to the jabbination was the same as yours. But one of the whole issues for me was also freedom of choice. If you want to have it, fill your boots. But don’t tell me I have to (especially when the logic seemed to be ‘mine doesn’t work, that’s why you have to have it’).

“Conspiracy theorist” is one of those things that people call you, like “Terf” and “Anti-Vaxxer” and you’re meant to feel offended, because, reasons.

I no longer accept the snide term “conspiracy theorist” and whenever it is levelled at me I swiftly correct the offender and tell them “no. Conspiracy Realist.”

The people who call you a “conspiracy theorist” are “conspiracy deniers”!

Journalist B returns insult to Journalist A.

What would be beneficial is more investigative journalism to answer the question she asks twice “FOR WHAT?”.

Those responsible may have become complacent and their perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased.

I do enjoy your last sentence.

I seem to have heard this phrase before. I shall ask my sage friend who was there in 2020. Never forget.

All I would say to the accusers is, if you ever wondered how you would have behaved in Germany during the 30’and 40’s look how you behaved during the scandemic and you will have your answer. We have more “Good germans” in this country than those who resist, my trust in my fellow citizen has been wiped out having been on the receiving end of their “goodness”

I can only sadly agree.

agree.

At the risk of repeating myself again I cannot forget Alison Pearson on the Telegraph’s Planet Nornal supporting Vaccine Passports. Sorry but that’s unforgivable. For all her “wasn’t I wonderful” antics you wonder how long her ilk would take to flip back to when we’re told to lockdown, mask up and compulsory get jabbed again.

Hi Epi – I don’t know whether Alison Pearson changed her mind, but on Planet Normal 18 Feb 2021 she says re covid passports that she is “on the fence”. Bad enough maybe, but not supporting them as such. This was also at a time when she and Liam Halligan were 100% pro-vaccine because they (like many at that time) trusted scientists and the so-called experts. I bet she isn’t so trusting now – and nor are we.

I googled it and the only reference I found was her saying that the passports were illogical. Happy to be corrected if somebody can find an article where she was in favour.

Those using HCQ – it seems to be assumed that the disease they were treating was C19. Was it?

Another legacy is that people feel empowered to wear masks whilst breaking the law, as evidenced by the blockading of a migrant detainee bus yesterday.

The police were seemingly unconcerned by these deliberate attempts to obscure their identities.

The “Conspiracy” was NOT a Theory & teh ONLY Conspiracy, was By Politicians AGAINT WE THE PEOPLE