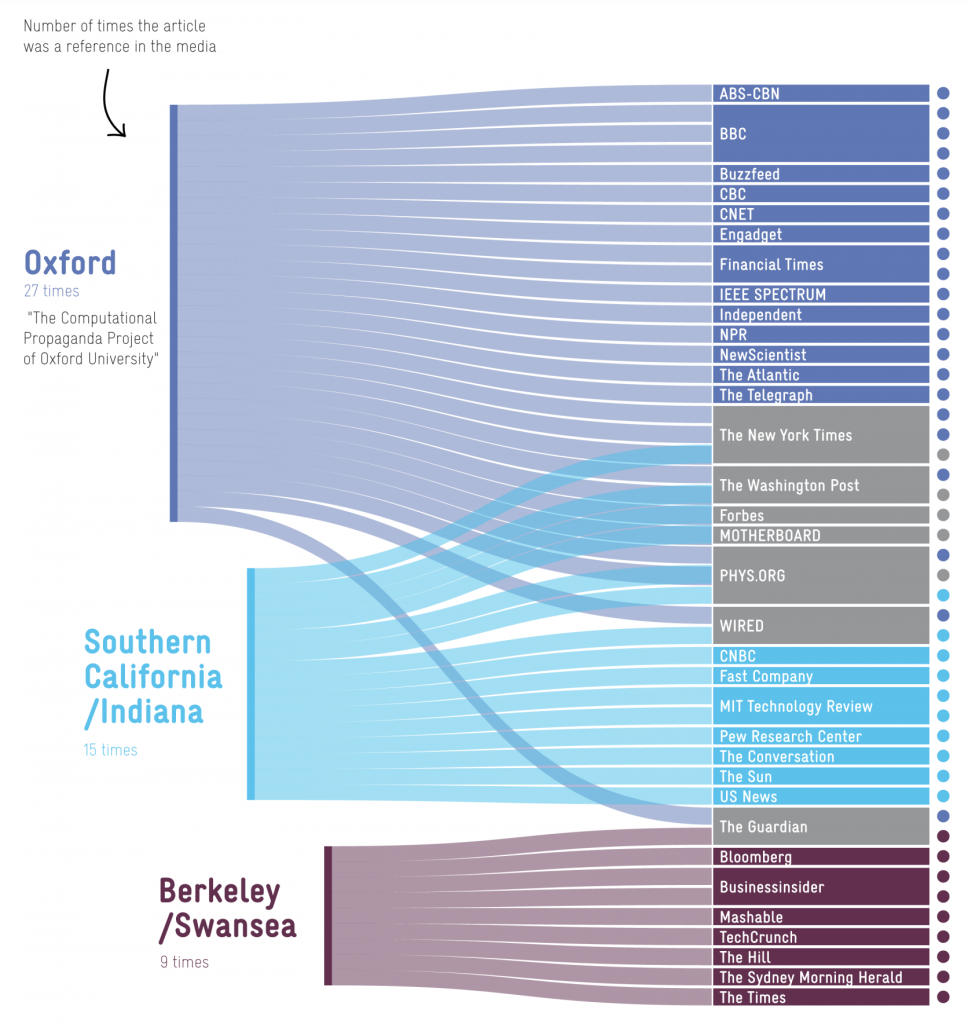

Since 2016 automated Twitter accounts have been blamed for Donald Trump and Brexit (many times), Brazilian politics, Venezuelan politics, skepticism of climatology, cannabis misinformation, anti-immigration sentiment, vaping, and, inevitably, distrust of COVID vaccines. News articles about bots are backed by a surprisingly large amount of academic research. Google Scholar alone indexes nearly 10,000 papers on the topic. Some of these papers received widespread coverage:

Unfortunately there’s a problem with this narrative: it is itself misinformation. Bizarrely and ironically, universities are propagating an untrue conspiracy theory while simultaneously claiming to be defending the world from the very same.

The visualization above comes from “The Rise and Fall of Social Bot Research” (also available in talk form). It was quietly uploaded to a preprint server in March by Gallwitz and Kreil, two German investigators, and has received little attention since. Yet their work completely destroys the academic field of bot research to such an extreme extent that it’s possible there are no true scientific papers on the topic at all.

The authors identify a simple problem that crops up in every study they looked at. Unable to directly detect bots because they don’t work for Twitter, academics come up with proxy signals that are asserted to imply automation but which actually don’t. For example, Oxford’s Computational Propaganda Project – responsible for the first paper in the diagram above – defined a bot as any account that tweets more than 50 times per day. That’s a lot of tweeting but easily achieved by heavy users, like the famous journalist Glenn Greenwald, the slightly less famous member of German Parliament Johannes Kahrs – who has in the past managed to rack up an astounding 300 tweets per day – or indeed Donald Trump, who exceeded this threshold on six different days during 2020. Bot papers typically don’t provide examples of the bot accounts they claimed to identify, but in this case four were presented. Of those, three were trivially identifiable as (legitimate) bots because they actually said they were bots in their account metadata, and one was an apparently human account claimed to be a bot with no evidence. On this basis the authors generated 27 news stories and 323 citations, although the paper was never peer reviewed.

In 2017 I investigated the Berkley/Swansea paper and found that it was doing something very similar, but using an even laxer definition. Any account that regularly tweeted more than five times after midnight from a smartphone was classed as a bot. Obviously, this is not a valid way to detect automation. Despite being built on nonsensical premises, invalid modelling, mis-characterisations of its own data and once again not being peer reviewed, the authors were able to successfully influence the British Parliament. Damian Collins, the Tory MP who chaired the DCMS Select Committee at the time, said: “This is the most significant evidence yet of interference by Russian-backed social media accounts around the Brexit referendum. The content published and promoted by these accounts is clearly designed to increase tensions throughout the country and undermine our democratic process. I fear that this may well be just the tip of the iceberg.”

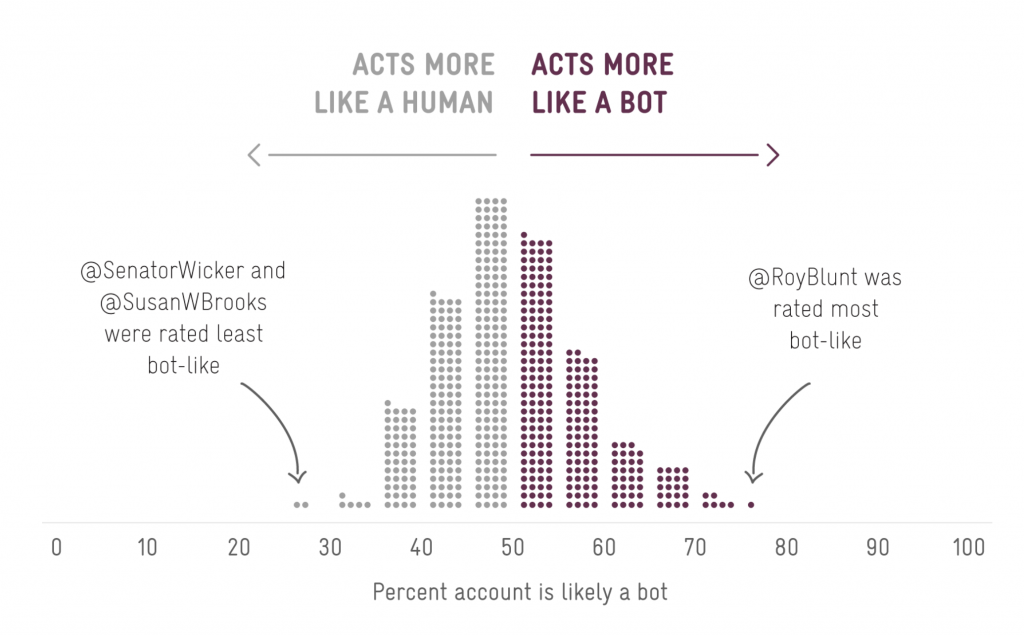

But since 2019 the vast majority of papers about social bots rely on a machine learning model called ‘Botometer’. The Botometer is available online and claims to measure the probability of any Twitter account being a bot. Created by a pair of academics in the USA, it has been cited nearly 700 times and generates a continual stream of news stories. The model is frequently described as a “state of the art bot detection method” with “95% accuracy”.

That claim is false. The Botometer’s false positive rate is so high it is practically a random number generator. A simple demonstration of the problem was the distribution of scores given to verified members of U.S. Congress:

In experiments run by Gallwitz & Kreil, nearly half of Congress were classified as more likely to be bots than human, along with 12% of Nobel Prize laureates, 17% of Reuters journalists, 21.9% of the staff members of U.N. Women and – inevitably – U.S. President Joe Biden.

But detecting the false positive problem did not require compiling lists of verified humans. One study that claimed to identify around 190,000 bots included the following accounts in its set:

The developers of the Botometer know it doesn’t work. After the embarrassing U.S. Congress data was published, an appropriate response would have been retraction of their paper. But that would have implied that all the papers that relied upon it should also be retracted. Instead they hard-coded the model to know that Congress are human and then went on the attack, describing their critics as “academic trolls”:

Root cause analysis

This story is a specific instance of a general problem that crops up frequently in bad science. Academics decide a question is important and needs to be investigated, but they don’t have sufficiently good data to draw accurate conclusions. Because there are no incentives to recognize that and abandon the line of inquiry, they proceed regardless and make claims that end up being drastically wrong. Anyone from outside the field who points out what’s happening is simply ignored, or attacked as “not an expert” and thus inherently illegitimate.

Although no actual expertise is required to spot the problems in this case, I can nonetheless criticize their work with confidence because I actually am an expert in fighting bots. As a senior software engineer at Google I initiated and designed one of their most successful bot detection platforms. Today it checks over a million actions per second for malicious automation across the Google network. A version of it was eventually made available to all websites for free as part of the ReCAPTCHA system, providing an alternative to the distorted word puzzles you may remember from the earlier days of the internet. Those often frustrating puzzles were slowly replaced in recent years by simply clicking a box that says “I’m not a bot”. The latest versions go even further and can detect bots whilst remaining entirely invisible.

Exactly how this platform works is a Google trade secret, but when spammers discuss ideas for beating it they are well aware that it doesn’t use the sort of techniques academics do. Despite the frequent claim that Botometer is “state of the art”, in reality it is primitive. Genuinely state-of-the-art bot detectors use a correct definition of bot based on how actions are being performed. Spammers are forced to execute polymorphic encrypted programs that detect signs of automation at the protocol and API level. It’s a battle between programmers, and how it works wouldn’t be easily explainable to social scientists.

Spam fighters at Twitter have an equally low opinion of this research. They noted in 2020 that tools like Botometer use “an extremely limited approach” and “do not account for common Twitter use cases”. “Binary judgments of who’s a “bot or not” have real potential to poison our public discourse – particularly when they are pushed out through the media …. the narrative on what’s actually going on is increasingly behind the curve.”

Many fields cannot benefit from academic research because academics cannot obain sufficiently good data with which to draw conclusions. Unfortunately, they sometimes have difficulty accepting that. When I ended my 2017 investigation of the Berkeley/Swansea paper by observing that social scientists can’t usefully contribute to fighting bots, an academic posted a comment calling it “a Trumpian statement” and argued that tech firms should release everyone’s private account data to academics, due to their capacity for “more altruistic” insights. Yet their self-proclaimed insights are usually far from altruistic. The ugly truth is that social bot research is primarily a work of ideological propaganda. Many bot papers use the supposed prevalence of non-existent bots to argue for censorship and control of the internet. Too many people disagree with common academic beliefs. If only social media were edited by the most altruistic and insightful members of society, they reason, nobody would ever disagree with them again.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Very interesting article from an expert in the field. Thanks Mike!

My only problem with this is that Mike Hearn proclaims himself an expert. I am not suggesting he isn’t, but as it stands it is an uncorroborated assertion.

I’ll provide direct evidence in a moment, but do you think I should have left that part out? As the article notes, no actual expertise is required to spot or understand these problems. The part about my background adds a bit of human interest and perhaps makes the article more convincing to some people, but the first articles I wrote for the site were anonymous, exactly to stop people getting distracted by irrelevant credentialism. Now I see your comment I’m starting to regret mentioning my bot related expertise at all because, after all, if there’s a theme to the articles on this site it’s that credentials don’t seem to mean much – at least not academic credentials.

Anyway.

In 2013 I was published on the official Google blog. That article discusses a different system I led the design on. It uses the bot detector as part of blocking account hacking, but additionally does many other things, so it doesn’t dwell on bots specifically. I also gave a talk on stopping spam, in a formal capacity as an employee, at an internet engineering conference in 2012. The bot detector is obliquely mentioned at one point along with various other spam fighting techniques, but again I don’t dwell on it or provide many details because it was at that time a rather unique technology that provided competitive advantage to the firm.

I’m curious though. Now you know that, does it really affect your opinion of what the article is about? Or were you just objecting to the lack of provided evidence (i.e. you don’t trust Toby to vet writers for the site).

I have read all your articles, whether anonymous or not; it is patently obvious to me, not being a programmer but having a serious interest in business and the truth, that you know what you are talking about. Maybe people should look at your biography online – Google allows one to look at your credentials for writing the reports that you do. That is unless everything one reads on the internet is spam and a false representation of reality, which it probably is in certain areas.

Thanks.

I found your article compelling and your criticisms chimes with the ones I have of the broad swathe of corrupt “scientific” opinion.

I have no doubt that Toby does an admirable job in vetting contibutors to the full extent of his capbility.

But you miss my point, you state that other bot “experts” use “their self-proclaimed insights” and yet your insights are also self-proclaimed. Do you not see the contradiction?

At the end of the day it has to be an act of faith, whether to believe you or not. I happen to believe you but I don’t want you to weaken your case.

I see your point. I think it’s hard to satisfy everyone with something like this.

The article has two parts. The first part, about why social bot papers aren’t reliable, should stand alone and be equally convincing without any attribution because all the claims have links, so you can directly explore the evidence, if you so wish. No acts of faith should be necessary. In fact you could make your own list of human Twitter accounts and see what the Botometer makes of it. That might be interesting.

The second part only makes one claim of any significance, which is how “state of the art” bot detectors really work. Indeed, because modern anti-bot techniques are proprietary this is difficult to provide any citations for and relies on my (ex-)institutional credibility. You could read actual spammers talking about it, because I gave a link that shows you some of those discussions. Or you can assume that part is all false if you like, or take it on faith: it’s not really important. It might be interesting for other programmers, and some people would find it enhances the credibility of the article, but is actually irrelevant to the core argument about the reliability of social bot research.

I’m not sure there’s any contradiction in assertions of the form, “those people aren’t experts, we are the real experts” as long as some compelling evidence is provided. If you read carefully, I’m not actually self-proclaiming expertise. The proclamation is via past employment. Whilst universities sort of ambiently imply that their academics are always experts, university administrations don’t directly judge the quality of that expertise due to the doctrine of academic freedom. In some sense academic expertise is self-proclaimed: nobody outside other academics in the same field is judging it. In contrast, any tech firm directly assesses the expertise of its employees, and the market directly assesses the expertise of the firm. There’s no equivalent of academic freedom to protect employees if they go off the rails and start making untrue claims.

In the end though, all this is not really here or there. I threw in that bit because it’d be kind of weird to write an article about bots without mentioning at all that I used to do it as a job. But apparently it’s just acting as a distraction and putting people back in “credentials mode”. That’s a pity.

OMFG. Haven’t you heard of Kees Cook’s crusade against the non-existent problem of erroneously omitted break statements in switches in the Linux kernel? That’s the kind of expertise one can expect from large companies like Google. It’s called academic groupthink.

I basically stopped reading LWN regularly because these gushing statements about nothing where too annoying and the all-out personal attacks on anyone criticizing one of it’s golden calves the OSS-community is rightly (in-)famous for, too.

I would be interested in seeing a subsequent article to this one with some mroe technical insights, whilst not all of DS’s audience might appreciate them i think some of us would be fascinated to hear more.

Try watching the talk I linked to above. It is for a technical audience and covers a variety of spam fighting topics. It’s not specific to detecting bots but you might find it interesting anyway.

so a bit like Climate Change science then?

Glad you write here Mike. Very insightful. I am now at the point where it’s almost impossible to know what is fact or fiction with these people.

“….and once again not being peer reviewed, the authors were able to successfully influence the British Parliament….”

And this is where the whole paper above falls down.

It is NOT THE CASE that bots, live people or anyone are able to “successfully influence the British Parliament”. The boot is completely on the other foot.

It is not the case that people are looking for real evidence. The people making the policy are activists looking for ‘evidence’ to support what they want to do anyway. Doesn’t matter if its fake or real – it just has to be something they can say.

Whether it comes from a robot, or whether you smear it by claiming it is from a robot – these are irrelevant questions. the point is that you are driving a policy and you need some story to back it up.

Truth is so last century….

If Damian Green was driving a policy of believing that the Russians were responsible for the decision by the British public to vote to leave the EU, if follows that the use of fraudulent, or false, Botometer data to support his position clearly demonstrates that Parliament HAS been influenced; if it was not so, why did Damian Green mention it in support of his view that the referendum was targeted by Russia?

In the end, the crap that is the majority of Twitter and other social media balances out – Bot or Not. It’s just like the rain from heaven. As a problem, its one of of education (in the widest sense), not of source. The total capture of the MSM is, in my view more problematic, because it insidiously creeps into every corner.

… but I do agree that any censorship assault does need opposition.

> the crap that is the majority of Twitter and other social media balances out

Censorship is there to ensure that it does not…

One of the creepy parts is they don’t even need to censor hard, whilst all of us converted sceptics can thankfully find sceptical content without much effort (for now), people in the mainstream never get that initial exposure to a diverse view which they need to start breaking their bubble.

Sounds very similar to the ‘research’ that said people like Tim Pool, Joe Rogan and Carl Benjamin (amongst many others who obviously weren’t) were alt-righters because they debated or called out those (IMHO) nutbags.

Part of me would suspect that for bot vs human diagnostics at the behavioural level the real thing to look for is:

a) accounts which only or almost only post messages which are exact repeats of those on other accounts

b) accounts set up just to make a brief series of posts then ceasing activity, typically as part of a large number of similar accounts in the same timeframe

c) accounts which post the same message every time with one or two variabels changed, these are usually bots which announce themselves to be bots and say things like “weather station at cross fell reports 12 celsius” or “tomorrow’s times headline will be…”

d) accounts where they only action they ever take in resposne to other accounts trying to communicate with them is a simple form of reply generated either according to randomness (likely irrelevant responses) or some sort of chatbot (picking on a key word and just commenting on that)

I’d love to see a proper analysis of the bot problem on Twitter, in particular the role of China (e.g. what happened with lots of accounts clamouring for lockdown).

A couple of times I’ve got replies on Twitter from random accounts – usually when I’m replying to an (anti-lockdown) tweet. When I check the profile of the person who sent the reply to me, they haven’t got many tweets / followers. There’s definitely a bot problem on Twitter.

It wouldn’t matter so much if politicians and the media didn’t confuse Twitter with the rest of the country!

For better or worse nobody outside the tech firms themselves would be able to do such an analysis reliably, and it’s unlikely they’d publish anything.

Defining bots as any accounts without many followers or tweets is the sort of problem that undermines these academic papers. Those accounts are much more likely to just be people who don’t use Twitter much.

There certainly have been bots on Twitter, but bots normally have commercial aims. They aren’t the sort of bots being talked about in these papers. Gallwitz & Kreil point out that the underlying assumption driving accusations of botting is that people’s political beliefs can be significantly altered by simply being exposed to tweets or retweets of hashtags. That is ultimately a rather large ideological assumption about human nature. At the very least, these papers never seem to show actual experimental evidence proving that artificial tweeting can change people’s politics. The effectiveness of the strategy is just taken for granted.

I’ve seen a couple of tweets shared where people gather evidence of lots of duplicates posted by various accounts. I think it would be interesting to investigate duplicate tweets like that. But that would be a hard job. I do agree that it would be a hard problem to really get to the bottom of apart from those tech firms.

And yes, completely agree about the ideological assumptions about human nature. It’s what the last 18 months have been about really. Ideas are dangerous, if people think about them they might change their minds – and that would never do!

Blimey, I’m a bot! Who knew?

Interesting article.

BTW my main criticism of the current “ReCAPTCHA” system is that it sometimes asks you to identify, for example, all the images of traffic signals. The trouble is sometimes some of those images are of such crap quality it’s almost impossible for me as a Brit. (and probably others) to know whether it is indeed a US type of traffic signal, or is some bracket or other type of lamp etc – then comes the need to “do it again” when you get it wrong!

Maybe it’s just me…

It’s not just you. The fact that some people fail CAPTCHAs is a well known problem with them. They’re meant to be puzzles that humans can solve but AI can’t. Lots of problems here: blind people can’t solve them, modern AI easily can, cultural differences (“click the school buses” etc), bad image quality, mistakes and so on.

We realized a decade+ ago that advances in AI would render these sorts of silly intelligence tests irrelevant. That’s why I started designing a new type of bot detector, the one that’s mentioned in the article. The challenges you’re talking about are ReCAPTCHA version 2. ReCAPTCHA v3 doesn’t use click-the-images tests at all, in fact, it doesn’t use any visible task. Separating humans from bots by asking the user to complete some sort of intelligence test is dead, and the industry is phasing it out.

Unfortunately CAPTCHA puzzles will probably never go away completely because the concept behind CAPTCHAs is easy to understand and open. Therefore they’re quite easy to make. The techniques behind polymorphic VM based bot detectors are proprietary trade secrets and they’re very difficult to make work well. So, to use them sites have to rely on Google or a few other companies.

Thanks Mike – glad it’s not just me. Lol!

https://txti.es/covid-pass/images

Found this description of living in Lithuania under a stringent covid pass law terrifying.

The author seems to hope that Lithuania has behaved eccentrically in imposing so many ruthless laws against the unvaxxed, but sadly the situation bears out the truth of the Canadian Report leak we read eighteen months ago – the unvaxxed will live under lockdown forever, and be treated as a threat to the rest of society.

The necessary document that allows you your limited “freedoms” is called “the Opportunity Pass.”

You couldn’t make this stuff up.

Credit to the reddit group for finding this

https://www.reddit.com/r/LockdownSceptics/comments/plwof5/todays_comments_20210911/