Lionel Shriver is the bestselling author of 15 novels, including the Orange Prize-winner We Need to Talk About Kevin, and a prolific journalist currently with a fortnightly column in Britain’s the Spectator. Her work has been translated into 35 languages.

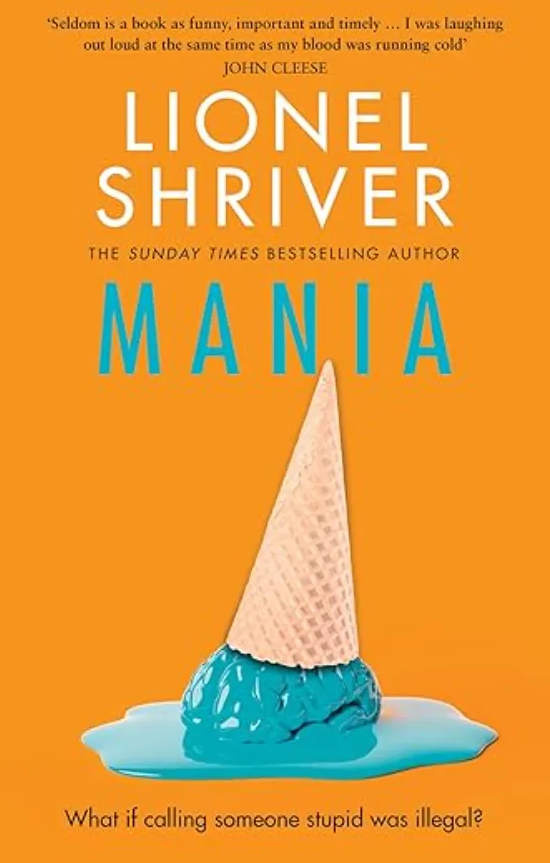

Her new novel MANIA is published April 11th 2024 (Harper Collins).

First of all, I must say I thought MANIA was phenomenal. It’s darkly funny and uncomfortably accurate about the appetite our society seems to have for ideas we would have firmly rejected just a couple of decades ago, such as the idea that women can be men and men can be women. In the ‘ALT’ (alternative) world of MANIA this destructive derangement takes the form of the ‘Mental Parity Movement’ where discrimination based on intelligence is illegal.

The books contains allusions and similarities to manias that people will recognise such as transgender theory, lockdowns, vaccine mandates, critical race theory, the climate catastrophe cult, affirmative action etc. Which of those specifically inspired you to write MANIA? When did you start tracking them and why?

A social mania is so all-encompassing that I hardly needed to ‘keep track’ as one followed the other. All that’s required is to take a step back and recognise: everyone has gone nuts. Everyone is reciting exactly the same thing over and over again. Everyone thinks exactly the same thing and is consumed by exactly the same thing. Any dissent turns people into crazed animals. The media, academia and Government are all disturbingly in accord. Oh, I see. It must be another social mania. One can take some comfort in ‘this too shall pass’, but it will only pass, apparently, to make way for another mania.

I set the novel starting in an alternative 2011, because it was in 2012 when I identified the first of the recent hysterias took off — the rage for transgenderism — and I wanted to get behind them and fashion my own mania. If anything, the mania I invented most resembles our sudden obsession with pretending to change sex, because virtually overnight it becomes holy writ that you mustn’t ever impugn anyone else’s intelligence, much as virtually overnight transgenderism also became ‘the last great civil rights fight’, and to emit a single discouraging word about ‘trans’ would be guaranteed to destroy your career and reputation. But I am passing larger comment on the lot of them: #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, DEI and Covid, which was itself a mania — the infection fatality rate of the disease especially for anyone but the very old did not merit our draconian response — and which gave birth to sub-manias (the love of lockdowns, the cult of the vaccine, the hysterical faith in masks). The climate ’emergency’ or ‘collapse’ or ‘global boiling’ or whatever we’re calling it now shows every sign of being another one.

We like to think we are ‘modern’, as every population in the present has always fancied themselves, and we like to think we’re too rational and scientific to subscribe to lunacies like phrenology or bloodletting with leeches. But we’re the same as we’ve always been, just as vulnerable to getting seized en masse by goofball ideas as we ever were. ‘Some people are born in the wrong body’ is right in there. One of the passages in MANIA I’m most attached to is the one in which the narrator explains that she used to be confounded by mass atrocities of the past, but now they all made sense: Nazi concentration camps, Pol Pot’s killing fields, Stalin’s show trials, Mao’s cultural revolution. That’s what I concluded after Covid, when in the land of the Magna Carta literally overnight people abdicated every civil right that they had the very day before imagined to be their birthright: free speech, freedom of assembly, a free press, free movement, even the right to leave your own home. Obviously people will believe anything, and for something like National Socialism to triumph in the U.K. it would take Adolf Hitler at the most about three weeks.

You quoted Jung at the beginning of the book. As someone who went on the record saying that the U.K. was suffering from a psychic epidemic during lockdown ‘mania’, I revelled in the book’s biting references to the lockdowns, vaccine mandates and money-printing instigated by “the morons in control of the country”. Do you think society is in the grip of a psychic epidemic?

We’re continually in the grip of one psychic epidemic or another — remember the ‘recovered memory’ scandal of the 1990s (which wasn’t perceived as a scandal until much later), or that same decade’s consuming obsession with pedophilia? What’s changed is the rapidity with which people suddenly embrace one prescribed view, and also the ease with which these mind viruses now spread internationally. So you had South Koreans marching down their streets chanting ‘Black Lives Matter!’ when the country basically doesn’t have any black people. Pre-internet, it would have been less likely that Britain would adopt woke ideologies from America wholesale. Now the infection spreads instantaneously. I am trying to call attention to the dangers of our credulity — or, to get fancy, our susceptibility to mass formation psychosis — as well as to examine what it is about some people that makes them immune. The most heartening aspect of the last 15 years for me has been the emergence of a cadre of independent thinkers who have been willing to risk their careers to say the suddenly unsayable. They give me hope for the future. You’re one of them, Laura.

I think the proof of how scarily spot on MANIA is, is not just how recognisable it is in general, but that some of the things you wrote about have actually manifested. Here are two particular examples. First, it becomes dangerous to get surgery in MANIA’s ALT world, because of the degradation of medical training standards; similarly there have been stories in the past few years about doctors and hospitals refusing care to patients who complain about mixed sex wards or using preferred pronouns. Second, the idea of ‘discrimination’ based on ability being verboten should be ludicrous, but the Russell Group universities recently issued guidance that saying the most qualified person should get the job is a ‘microaggression’. Do you think your dark allegory could actually come to pass? Could we be that stupid as a society?

Yes, the notion that all people are equally intelligent is just a hair away from where we are now, and that’s as I intended. Medical schools in the States are already lowering standards and eliminating test requirements because all they care about is ‘diversity’. Merit is already under attack. It has been under attack in the U.S. for 50 years. Affirmative action was installed in the early 1970s, and I still remember when I first learned about it. I was 16. I was appalled. I couldn’t see how institutionalised unfairness would end well. It hasn’t. For some years now, I’ve been warning the U.K. that if you bring in racial quotas — for that is what ‘affirmative action’ demands — you will never get rid of them. The rot sets in quickly. Nothing gives me the willies like the fact that air traffic control is now consumed with diversity, equity and inclusion. I travel a lot…

You have talked in the past about your religious upbringing. In the novel, Pearson comes from a Jehovah’s Witness family, she has a man’s name, like you, and is prepared to go against the grain. Although her IQ is just 107, how much of you is there in Pearson?

Oh, sure, Pearson (and is that a man’s name? it’s more traditionally been a surname: “The name Pearson is primarily a gender-neutral name of English origin that means Son Of Piers/Peter. Medieval English surname.”) and I have plenty in common. I rejected my Presbyterian upbringing, though Jehovah’s Witnesses are far more oppressive and much scarier to rebel against. Pearson as a kid was dumbfounded (of course, that’s a word that in MANIA will get you cancelled) why her peers raised in the same religious tradition simply went along with a creed that made their lives miserable. Whyever didn’t they declare like Alice, “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”? The most central thing Pearson and I have in common is a resistance to conformity. I’ve never been one to get with the programme. But being constitutionally odd man out (or woman out) is dangerous right now, and I’m amazed that so far I’ve got away with being so ornery and uncooperative.

Would you prefer to hang out with Pearson or Emory?

Pearson’s best friend Emory is stylish, socially adept and droll. She’s good company, and she’s actually smarter than Pearson, not to mention savvier, since she realises early on that resisting the Mental Parity Movement would thwart her aspiration to become a television commentator. Pearson is more awkward and less social. She’s stubborn, and she won’t bend to orthodoxy; she’s self-destructive. She may not be academically gifted, but à la Orwell she refuses to say that two plus two equals five. I’m afraid if I hung out with Emory she and I would eventually have a catastrophic falling out. Which funnily enough is what happens in the novel…

What do you think about IQ tests? And do you know what your IQ is?

Ha! Interesting question. IQ tests measure something, though I’d be the first to concede there are different forms of intelligence. I only took an IQ test once when I was very young (maybe nine?) I didn’t know I was taking an IQ test at the time. I think the result was something like 125, which I frankly found insulting. (I still do.) See, my older brother tested as a ‘genius,’ meaning his score was at least 145; again, I think it was over 150. So f**k 125. I wanna take that test over again!

Please assume the role of an Oracle and describe how Great Britain ( ALT-Great Britain perhaps) will look in 20 years’ time.

Immigrants and their children will form the majority. You will be something like 30% Muslim. The country will be broke. Public services in future will make today’s seem positively Japanese. Net Zero will have been completely abandoned, but not before doing untold economic damage and leaving the U.K. with insufficient energy sources. There will be blackouts, and typically for Britons everyone will get used to them, just as they once got used to lockdowns. Immigration will start to slow, because there is no reason to pay money to enter another Third World — oh, sorry! developing world — cesspit. It is entirely possible that the pound will have collapsed, on the heels of the American dollar having collapsed, since both countries will have accumulated so much debt that no one will loan them money anymore, so they will both have resorted to money printing, with the usual consequences. Want me to go on? No? Didn’t think so.

For me, a depressing take away from the book is simply that people can be so ‘stupid’, as a catch-all term. As a society, we are subject to destructive hysterical cycles which undermine what we should be capable of. Groupthink (a.k.a. social conformity) has sound evolutionary purposes but in large societies connected in real-time by the internet and social media, appears to be warping into something dangerous. I’ve been rolling this around my mind since the first horrific lockdown. The power of the totalitarian mindset can tear apart even the most important connection between parent and child. Lucy turns on Pearson, just as children have turned against their parents in communist regimes over and over. Big question: what do you think of people?

Some of my best friends are people.

That said, during the last 12 years I’ve been very disappointed in our species. Covid profoundly changed what I think of people, as it also changed my estimation of so-called liberal democracy. As for the latter, there is apparently little difference between our system of government and autocracies, because we collapsed to autocracy all over the West in a heartbeat. And here’s the thing: we don’t know what’s around the corner. It’s not always possible to recognise an irrational social mania when it’s first taking off. We have no idea what barmy idea will take hold next.

Which book have you most enjoyed writing?

Hmm, hard to say just one. But the process of writing the following was especially fun: Kevin: The Mandibles (see: the collapse of the dollar), Should We Stay Or Should We Go, and this one. With each of those, I kept laughing out loud over my keyboard.

What is your proudest and most important achievement? And if that achievement is not your writing, which of your writings are you most proud of?

Oh, the writing is all I’ve achieved, aside from a solid marriage, a great relationship with my younger brother and a passably mediocre tennis game. The novels are of more enduring importance (assuming anything I’ve written is of enduring importance) than the journalism, though I am proud of having stuck my neck out in non-fiction early on in relation to issues that were dangerous to tackle. I was one of the first to oppose lockdowns. I was one of the first to express dubiety about transgenderism. I was virtually the only person in my London social set who backed Brexit, though that was operating on the absurd assumption that the British establishment would take advantage of it; no such luck. As for which books I’m proudest of, I’d probably list all those novels that were the most fun to write. But I would also add so much for that — because while there’s always something to be said for novels that make you laugh, there’s also something to be said for the ones that make you cry.

What is the aspect of your work that people most disagree with and why?

I do not pander. I will not shovel a lot of horseshit about how ‘diversity is our strength’ and I will not use fashionable but idiotic formulations such as ‘people of colour’ (when saying ‘coloured people’ will get you sacked) or ‘LGBTQIA+’. Especially since I fiercely oppose racial quotas and uncontrolled mass immigration, my detractors believe I am a racist. That used to smart, and now does not affect me in the slightest.

Describe your biggest epiphany and how it shaped you?

It wasn’t a single moment, but coming to the conclusion that the IRA were the bad guys all by myself in my early 30s was my first genuine exercise of independent thought. (You would think this conclusion would be self-evident.) I lived for a dozen years in Belfast, and when I arrived I had no opinions about the Troubles whatsoever. So I was a blank slate. In time, I came to loathe Republicans and Nationalists in general. Nationalists were really the originators of identity politics, and having spent all that time in Northern Ireland may be one reason that today’s progressives get my goat. But Democrats in the U.S. were largely all in with the IRA back then, so this independent positioning of mine also broke my allegiance to liberal Democrats in my own country (that would include my parents). Ever since, I have spurned factionalism, and I try to make up my mind about matters one by one and not because ‘my side’ thinks a certain way.

If you could rewind a few of decades, would you choose a new career, or would you do something differently?

Nah. This career has worked out swell for me. Only one point of wistfulness: I used to be heavily involved in visual art, and I wasn’t a half bad ceramic figure sculptor. That side of my life has withered, because there isn’t enough time in the day to pursue visual art and still write journalism and book-length fiction.

If you were an absolute monarch for a day, what law would you introduce?

I would outlaw the use of the word ‘space’ unless you are talking about the night sky.

What is the most interesting thing you have learned in the last year?

That both major American parties have a death wish. If either party ran any other candidate for president other than the one it is in fact running, it would win. That is documented in the polls. This is the freakiest American election in my lifetime, and I am trying really, really hard to simply find it riveting, since otherwise I subside into misanthropic depression. That death wish, alas, appears to extend to the country itself. I am hard-pressed to say whether four more years of Trump or Biden will be more disastrous.

What is next for you?

I’m halfway through the first draft of a novel that takes on mass immigration, which is certain to destroy my career. Oh, well. Might as well go out with a bang!

MANIA is published in the U.K. April 11th 2024.

MANIA: What if calling someone stupid was illegal? In a reality not too distant from our own, where the so-called Mental Parity Movement has taken hold, the worst thing you can call someone is ‘stupid’.

Everyone is equally clever, and discrimination based on intelligence is “the last great civil rights fight”.

Exams and grades are all discarded, and smart phones are rebranded. Children are expelled for saying the S-word and encouraged to report parents for using it. You don’t need a qualification to be a doctor.

Best friends since adolescence, Pearson and Emory find themselves on opposing sides of this new culture war. Radio personality Emory – who has built her career riding the tide of popular thought – makes increasingly hard-line statements while, for her part, Pearson believes the whole thing is ludicrous.

As their friendship fractures, Pearson’s determination to cling onto the “old, bigoted way of thinking” begins to endanger her job, her safety and even her family.

Lionel Shriver turns her piercing gaze on the policing of opinion and intellect, and imagines a world in which intellectual meritocracy is heresy.

This article was first published on Laura’s Substack page the Free Mind. Subscribe here.

Stop Press: Toby Young will be interviewing Lionel Shriver on stage at the Hippodrome at the Free Speech Union’s launch party for her new book on April 15th. You can purchase tickets here – and it’s cheap as chips! £10 for FSU Members and £15 for non-members.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Emails suggest ex-NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo launched COVID-19 memoir project in March 2020”

Well, well, well…

Sing: 🎶What a bunch of fecking Eejits!🎵

“We are trans and cis together”

Vomit inducing nonsense…

For the non local Norwich City Council has been Labour controlled for years .These tools do not represent the good people of Norfolk in the main .

Their local electorate are skewed by three huge public housing areas plus the University. Am I surprised ? No not really lol

“Labour council staff take the knee prompting row with Salford residents”

Another group of public servants mistaking their misplaced sense of compassion for the green light to ignore their duty to the people who pay their wages..

Mr Floyd didn’t really deserve a lot of compassion really, and the whole BLM movement has proven to be ‘scam whitey’, but there you go..

F-me, their not still taking the knee are they?

That’s so yesterday!

The picture in that link makes me🤮🤮

Someone please, help them to their feet, dust them off ,wash their clothes and give them a good meal! Their so lost and needy bless them, it makes me tear 😢 up ! Chunts

The need to stop the WHO’s pandemic treaty and IHR amendments is getting more urgent by the minute.

Yesterday, the WHO appointed North Korea to its executive committee.

You could not make it up.

What could possibly go wrong?

Does anyone else feel the transition to Clown World is accelerating?

Hell yes, we all feel it! and its terrifying!

Just to add, I seriously feel the pain and frustration you do! This “new dawn” is frightening all of us who still possess our own brains!

Prof Kathleen Stock has written about her Oxford talk. *Spoiler* It was an all-round positive experience.

”Other supportive students in Oxford, neither feminist nor anti-feminist, just seemed fed up with being emotionally blackmailed into stifled silence by a small group of childish and histrionic narcissists — among which they doubtless would include the occasional lecturer. And from within each Union, the committee members responsible for inviting me were totally impressive, standing resolute against pressure and showing exemplary resilience in the face of harsh criticism from some peers.

In looking at some of the media coverage of my Oxford trip, it’s striking to me that certain journalists’ idea of balanced reporting is to interview, on one hand, Stock the supposedly offensive speaker, and on the other, students who say they feel threatened and frightened by my terrifying words. (The rough format goes as follows. Student: “I just feel exhausted constantly having to justify my existence every day!”. Interviewer: “What do you, Stock, say to the students who feel exhausted having to justify their existence every day?” Me, looking at said students, apparently with enough energy to drum and chant for hours: “Erm … I’m not sure. Maybe get their iron levels checked?”.)”

https://unherd.com/2023/06/the-oxford-kids-are-alright/

The recent World Health Assembly singles out Israel as a ”violator of human rights” and in true back to front, Clown World fashion, North Korea have the nerve to say this…

And check out the other countries condemning them. What a joke!

”North Korea, which was just elected to a 3-year term on on the WHO executive board, said it was “deeply concerned about the health conditions in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The prolonged occupation, illegal settlement activity, and discriminatory practices continue to negatively impact the living conditions of the population.”

https://unwatch.org/whos-2023-assembly-once-again-singles-out-israel-as-violator-of-health-rights/

That is classic. North Korea of course known for respecting the health conditions and ensuring no discriminatory practices of its own population. Alarmingly, North Korea get a seat on the board of the WHO…what on earth could go wrong with that?

Mogs, your the fount of all knowledge! Can you run for prime minister/president in all countries? Your wisdom is so needed right now

Well I don’t know about that, but I feel ready to achieve my PhD in ‘Cutting and Pasting’. 😆🎓🤓

Bless you, your a gem!

I wish I had your integrity 👍

That’s sweet of you to say Dinger. 😊 Kids holidays over here so got more down time..🌞

..while I agree with you that it’s hypocritical..I also think, that in relation to Palestine, it’s not entirely wrong either.

If you read the article you note that the ‘’spokesperson’ they feature is from UN Watch..which is supposedly an independent NGO, but which has very strong financial ties with the American Jewish Committee… they mention Syria..but only in relation to Russia bombing it (over three years ago)..they don’t mention the current illegal occupation of the USA in Syria, nor the USA’s theft of their oil and grain, nor do they mention the stringent US sanctions that are crippling Syria, nor the constant bombing raids by Israel….they mention Afghanistan, but again no mention of the USA’s occupation, or sanctions, nor the fact that they stole and still refuse to release millions of dollars of Afghani money.

I’m not particularly trying to pick a side here, and I’m not anti-Israel…. but the West doesn’t allow ‘the rest’ a platform in general…and I’m not convinced they get a fair deal when it comes to battling against the might that is the USA and the West’s established constructs. There are real global changes happening in the world, as we can all see..I think they need to be addressed in a different way than just saying one set is always right, while one set is always wrong?!

Yes, I agree. Not defending Israel. Just the hypocrisy and sheer nerve of countries such Iran and N. Korea finger-wagging about mistreatment of citizenry elsewhere. Plus to highlight the fact N. Korea were actually *elected* by the WHO. I mean, as if we need further confirmation of just how big a criminal outfit and significant threat to democracy they are. But leaders in the West will sign over our sovereignty in a nanosecond regardless.

And it got picked up ATL, in record time..LOL!!

“We are trans and cis together” – new religion?

Remember also how some churches flew flags saying “thank you NHS”? That was like a new religion too.

As for “memory loss during lockdowns”: it’s what the tyranny is hoping for, that people will erase it from their minds, as if it never happened, and they will forgive the politicians in time for the next election, and the next plandemic (which the tyrants seem certain will happen). I have no intention of forgetting anything, from the locked playgrounds, to children locked in their homes behind their rainbows, to the “be a superhero” coercion to mask up and roll up your sleeve, and we must remind Parliament about these deeds on a regular basis. They must never be forgiven or forgotten.

Labour party members in parliament worked with Conservatives in drafting the Coronavirus Bill 2000. Both houses of parliament passed the Coronavirus Act 2000 without division. The Scottish parliament gave formal Consent to the UK-wide legislation without a vote on it.

Scum, the lot of them.

Agreed 👍

Bang on! Here no,see no,say no! “Don’t mention the war, ….sorry…. vaccines!”

When the long sinuses blood clots stretch through their veins they may want an answer all of a sudden!

Seconded.

The FDA have just approved the new Pfizer RSV jab for 60+ year old, but if there’s one thing we’ve learnt ( we critical thinkers have learnt a lot, of course ) it’s that these claims of efficacy are totally bogus and not what they are widely touted in the media.

https://twitter.com/ITGuy1959/status/1664086303401558020

Placebos in medical trials have been eliminated & RRR used instead of ARR… Talk about gaming the system to achieve the desired outcome.

Rrr? Arr? Sorry I’m a bit thick, please explain

Relative Risk Reduction vs Actual Risk Reduction

RRR always gives a higher % than ARR thus making the product seem more effective. The covid injections we were told gave 95% protection. Dig down into the data & that was the difference between the ‘product’ & the placebo. Translate that into ARR & you get less than 1% ie not worth a damned thing!

All smoke & mirrors to dupe a population which is basically numerically illiterate.

Not thick, learning. We’re all learning on a daily basis.

Hope that this clarifies things for you

BB

…I still have a look at this short video every so often to remind me!!

For some reason it just won’t stick in my head!

Proff Norman Fenton….explaining relative risk v actual risk….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQlBZUc4Ao8

Andrea Jenkins should not display her inadequacy. What could the civil servants do if she arranged to meet in the nearest Spoons for a refillable coffee at £1.70 each.

“Climate protester left with block of tarmac stuck to his hand is jailed”

Leave him like that! Twat

Novak Djokovic almost always cheers me up. He’s annoying the French Minister for Sport, who one imagines is a good person to annoy: French Open 2023: Novak Djokovic stands by Kosovo message after criticism – BBC Sport

French sports minister Amelie Oudea-Castera said there needs to be a “principle of neutrality for the field of play”.

Oudea-Castera said she made a distinction for messages in support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s invasion, adding that she did not put Kosovo and Ukraine “on the same level”.

So a nice bit of the usual Western hypocrisy then? It’s ‘neutral’ to be against Russia..but not Kosovo…do these people ever listen to themselves…??

Tennis community was happy for some players to express support for BLM…

““Black people were three times more likely to receive Covid fines in England and Wales” – Those in poorest areas were seven times more likely to be fined, finds research into how police used emergency powers, says the Guardian. Are these the first signs of remorse from the pro-lockdown paper?”

Of course not. It’ll be some “anti-racist” nonsense. If you were against lockdowns, why would you care who it affected most – surely you’re against them for everyone? It reminds me of an exchange I had with an acquaintance mine, early on in proceedings. He’s a senior manager in the NHS. One of the reasons he gave that we should lock down and take covid seriously was that it disproportionately affected non-white people.

Of course it disproportionately affected folk with darker skin – their Vit D serum levels were through the floor & adequate Vit D levels reduced the severity of said illness & risk of being subjected to the death protocols in hospitals.

If only the data from the frontline medics had been utilised rather than censored….

But the government does have your best interests at heart…. Honestly….

Damn! that battalion of flying pigs has just crashed in flames…

What.? With all those multi-generational houses,and a tendency to spend their evenings in the streets with friends and neighbours, or praying five times a day.

“Electric car infrastructure creaks under demand”

So of your not well off enough to have a house you own, a private drive ,30 plus grand lying around in the first place, not to mention a caravan, a boat, a trailer, nowhere you need to go! Retired, solar panels and a healthy bank balance! Electric cars are just the thing for you! (About 5% of the population at best) I think evs have reached all the customers they are ever going to reach! It always was a niche product!

“Covid lockdown may have created similar memory problems to those that people who are locked up in prions”

Freudian slip?

Nice one😉

Meanwhile!: “BGT’s Amanda Holden glitters in sheer gown with sizzling thigh split”

Look over here! Oi, sheeple, here! (Click fingers loudly) Ignore the smoke and mirrors and the man behind the curtain!

‘The man behind the curtain’???

Although a bit rude about ‘her’ sheer gown it’s certainly the Amanda Holden story we might be bothered to read.

This is quite worrying….I haven’t seen this reported in any British media (naturally)…..when you remember that we live in a country that still keeps reporter Julian Assange in prison..and that only a couple of weeks ago was defending a US reporter detained by Russia….

“Britain has called for the release of a US journalist detained in Moscow.

No10 said Rishi Sunak stood ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with the US over its efforts to free Evan Gershkovich.”

https://thegrayzone.com/2023/05/30/journalist-kit-klarenberg-british-police-interrogated-grayzone/

British counter-terror police detained journalist Kit Klarenberg upon his arrival at London’s Luton airport and subjected him to an extended interrogation about his political views and reporting for The Grayzone.As soon as journalist Kit Klarenberg landed in his home country of Britain on May 17, 2023, six anonymous plainclothes counter-terror officers detained him. They quickly escorted him to a back room, where they grilled him for over five hours about his reporting for this outlet. They also inquired about his personal opinion on everything from the current British political leadership to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

….During Klarenberg’s detention, police seized the journalist’s electronic devices and SD cards, fingerprinted him, took DNA swabs, and photographed him intensively. They threatened to arrest him if he did not comply.