A rare thing has just happened: common sense has prevailed.

Last week, the English Football Association (FA) ruled that Manchester United winger Alejandro Garnacho would face no charges for a social media post celebrating his teammate André Onana making a vital last-minute penalty save in a Champions League match. Why would he face charges for such a thing anyway? Because, hoping to praise Onana’s physical prowess, he also posted two gorilla emojis alongside a photo of the goalkeeper in question – who just happens to be a very large black man from Cameroon.

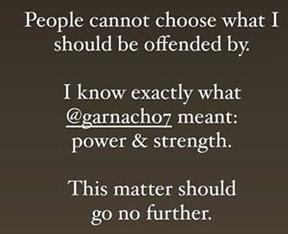

To his immense credit, Mr. Onana anticipated the inevitable FA-led witch-hunt against Garnacho that would follow if he stayed silent, quickly backing his team-mate with a post of his own:

Those are very sensible words: “People cannot choose what I should be offended by.” The trouble is, we no longer live in a terribly sensible world, and people are constantly going around deciding just that. This phenomenon does not yet seem to have acquired a specific name of its own, but I would like to propose we christen it ‘compelled offence’, the dark inverted twin of that other common scourge of contemporary discourse, ‘compelled speech’.

The FA’s approach in applying such compelled offence rules appears inconsistent, however. In 2009, the organisation banned Manchester City midfielder Bernardo Silva for one game and fined him £50,000 for a hastily-deleted tweet comparing a childhood photo of his then-team-mate and close friend Benjamin Mendy, a black Frenchman, to the ultra-cute brown-skinned mascot of a popular brand of Spanish chocolate-covered peanuts named Conguitos:

The golliwog-like Conguitos mascots, meaning ‘The Little Congolese’, have existed since 1961, causing little offence to most until 2020, when the death of George Floyd suddenly changed absolutely everything – even the hitherto obscure world of Spanish peanut advertising. The absurd hashtag #ConguitosLivesMatter began trending, and bizarre old images of blacked-up Spaniards cosplaying as the mascots were dredged up to shame the white race.

In their mascots’ defence, in 2020 the Spanish chocolate company Lacasa cited their “adorable nature” and frequent surveys proving the majority of Spanish consumers did not think the cartoons racist, but associated them with “fun times and positive energy”. Nonetheless, BLM campaigners began complaining that, even though the Spanish public were overwhelmingly not offended by them, they really ought to be. In the words of one “Afro-feminist communications expert” (you what?), the cartoon peanut-people were “a source of insult to an entire community” – i.e., all black people, everywhere.

But this just wasn’t true, was it? Unlike the professional peanut-haters of BLM Spain, back in 2019 Mendy himself was not remotely insulted, replying to Silva’s initial tweet with smiley face emojis. Mendy wrote a letter to the FA in Silva’s support, meaning even its own in-house offence-sniffers had to admit the post was not meant to be “insulting or in any way racist”, merely “a joke between close friends”. Nonetheless, the FA said, other random people who saw it “would have taken offence” on Mr. Mendy’s behalf; passing Afro-feminist communications experts, maybe.

“Can’t even joke with a friend these days,” complained Silva online, to which anti-racism in football organisation Kick It Out – whose entire continued existence presumably depends upon football appearing to remain absolutely chock-full of racism, even on occasions when it isn’t – responded that this was quite correct, such personal private relations were no longer allowed. “Racial stereotypes are never acceptable as ‘banter’,” Kick It Out said, knowing better than Mendy himself what he should and should not be upset by. The body then demanded “mandatory education” be given to Silva too, just to make sure he knew how to be friends with another adult human being in the correct, Stasi-approved, best-practice fashion.

Silva and Mendy’s black Manchester City teammate Raheem Sterling creditably said he didn’t think it was racist either, saying both Mendy and the Conguitos peanut-man had “both got small heads”, whilst their manager Pep Guardiola said it was just a standard piece of ‘lookey-likey’ humour. “The same thing happened a thousand million times with white people,” he argued. Indeed so – Gareth Bale is constantly compared to Donkey Kong with no threats whatsoever of any action being taken, unlike with André Onana.

By Kick It Out and the FA’s logic, the only chocolate mascot it would have been legitimate for Silva to jokily compare Mendy to would be the Milky Bar Kid. Then again, it turns out there is actually a white chocolate version of Conguitos on the market, whose front-of-package mascot looks just like the one in Silva’s original tweet, but albino. If Silva had been smart, his defence would actually have been “Whoops, I just posted the wrong sweet-wrapper”.

In 2021, another Manchester United player, Uruguayan striker Edinson Cavani, was banned for three matches and fined £100,000 after an acquaintance messaged him online to praise a recent match-winning display of his, to which Cavani innocently replied, in his native Spanish, “Gracias, Negrito”, translated in the British press as something like “Thanks, little black person!”

Immediately, the FA jumped in, eagerly labelling the post “insulting, abusive [and] improper”. And yet, the man at whom it was aimed did not feel it to be so – as far as can be told, he was not even black. Cavani himself called the phrase “an affectionate greeting to a friend”.

Actually, the word Negrito is a common term of endearment in Cavani’s native Uruguay, where it may refer merely to someone with dark hair or eyes. According to the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy, Negrito is often even a “word used tenderly by married people, couples or people who want the best for each other”, throughout Latin America.

Hispanic Uruguayans were up in arms over the FA’s punishment of Cavani, accusing the organisation of being racist itself, or of “suffering a colonial hangover”, in which it arrogantly sought to “globalise meanings” of words, imposing English conceptions of what constituted racist terminology onto foreign phrases and strutting around telling native Spanish-speakers what Spanish really meant.

Even better, the Uruguayan players’ union issued a strongly-worded statement, bemoaning the FA’s arrogance about assuming compelled offence on their members’ behalf:

Far from condemning racism, the English FA has itself committed a discriminatory act against the culture and way of life of the Uruguayan people. The sanction shows the English FA’s biased, dogmatic and ethnocentric vision that only allows a subjective interpretation to be made from its particular and excluding conclusion, however flawed it may be… [T]hrough its sanction, the English Football Association expressed absolute ignorance and disdain for a multicultural vision of the world… To sustain that the only way to obtain a valid interpretation in life is that which lies in the minds of the managers of the English FA is actually a true discriminatory act, which is completely reprehensible and against Uruguayan culture.

And yet, despite clearly being in the right, Cavani chose not to appeal the FA’s ruling, meekly accepting his unjust punishment out of what he called “respect for the FA and the fight against racism in football”, even though he was in fact the one who had just suffered from this very thing.

Given the FA’s recent reverse-ruling regarding Onana and Garnacho, however, doesn’t the organisation now owe Mr. Cavani his £100,000 back? With the innocent Uruguayan being inaccurately punished as a racist in this way, I actually feel quite offended on the poor fellow’s behalf.

Steven Tucker is a journalist and the author of over 10 books, the latest being Hitler’s and Stalin’s Misuse of Science: When Science Fiction Was Turned Into Science Fact by the Nazis and the Soviets, which is out now.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

What could possibly go wrong.

The threat to us of Chinese firms with connections to the CCP is almost insignificant compared to the immediate and massive threat we face right now on a daily basis from our own ruling class who have in the last few days revealed with astonishing clarity that they don’t understand the difference between the environment and climate change.

Boris Johnson and Kemi Badenoch and presumably all the rest of them thought Net Zero was a good idea because it would improve the environment, clearly not realising that it is a project to eliminate CO2 which is no way related to how clean the environment is.

That level of stupidity and ignorance from people with actual power over us is far far more dangerous than any Chinese company.

Indeed – and which was the more dangerous – the “Chinese virus” or the catastrophic “reaction” to it by governments all over the rich world?

Never trust anything branded SMART – In a past life, we had work objectives that were meant to be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timed.

In that line of business, few objectives ever survived contact with reality for very long.

Know thine enemy.

The Chinese will rule the world without a single shot being fired, and our dopey government thinks the Chinese are a state to trust with our energy supply and infrastructure. Barking mad.

That is their plan, and has been for many, many years…

Bogeyman China. Just imagine what would happen to UK’s energy grid if China switched off all our solar power – nothing?

If you do not wish to buy Chinese products then buy another country’s products or, better still, make your own.

Ah but that would require thinking further ahead than a week next Tuesday, AND it might be a few quid more… can’t have that!